Geos Roguevalleyva2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Astronomy Baseball Bicycling Birds

Morrison Park A 1187 Rogue River Hwy. Art 2 courts, lighted Westholm Park Artist’s Association Josephine Co. Corner of SW Wildwood and I Streets Carol Smith 541-479-1602 1 court, unlighted Enjoy monthly meetings at the Fruitdale Grange that in- Redwood Park clude short business updates, artist exhibit news, network- 1395 Dowell Road ing and refreshments, followed by demonstrations, pres- 1 court, unlighted entations, critiques or idea sharing sessions. Call for meeting information. Bicycling VacieAnna Berry’s Whitehorse Studio Bicycle Safety 220 NW 6th St., #206 Crime Prevention Office 541-450-6200 541-474-9430 Art classes offered for ages 5-18 years. (Some adult in- BMX struction available.) Small groups or individual. Tuition River City BMX includes all supplies. Studio located above the TaeKwonDo 1380 Pansy Lane studio on 6th St. 541-471-0269 Racing every Tuesday and Saturday year-round. Astronomy Grants Pass Skate Park Grants Pass Astronomers 820 SE M Street John Bunyan 541-226-6135 541-471-6435 www.grantspassastronomers.com Bike hours at the skate park 10 AM to 12 Noon, 3 PM to 4 Scope loaner program, club meetings, star parties. PM, daily. Helmets required. Clubs/Rentals B BikeKraft Baseball 785 Rogue River Hwy American Legion Baseball 541-476-4935 GPNuggetsBaseball.org Year-round weekly bike rides for advanced mountain bike Rick Chapman 541-479-5757 riders. Riders meet every Wednesday at 6:00 PM. Bring Grants Pass Little League helmet and water. Call Richard for more information. American League (north of the Rogue River) Don’s Bike Center Hotline 541-787-5037 211 SW G St National League (south of the Rogue River) 541-471-3494 Hotline 541-441-8256 Rogue Valley Mountain Biking Club Boys and Girls Club 541-479-5258 Basketball For youth 10-18 years of age. -

Wine in the Rogue Valley: from Peter Britt to Rebirth

Wine in the Rogue Valley: From Peter Britt to Rebirth By Willard Brown Southern Oregon University History 415 Fall, 1999 Introduction In a previous paper this author explored the origins of grape growing and winemaking in the in the Rogue Valley of southern Oregon. Peter Britt was credited with establishing the first vineyard around 1855,arrd later, he produced wine under the name Valley View Vineyards. By the end of the century Britt had introduced premium wine grapes from California and had disseminated cuttings to other growers for propagation and vineyard development.1 Following the death of Britt in 1905, his winery ceased operating-2 and after 1916 when Oregon prohibition took effect, wine production in the valley ceased altogether. It would be nearly sixty years before it would resume. No single factor can explain this extended absence, but a number of successive and sometimes interrelated events impacted the industry and delayed its return. In the following, we will examine these events and evaluate their role in the decline and the rebirth of this industry. The End of the Beginning Grape growing and winemaking in the Rogue Valley reached its apogee around 1890. At that time nearly seventy-five acres of vineyards were in production and a number were recently planted. Grapes were sold locally, sent to the Portland market, and used in the manufacture of wine and brandy.2 By 1903 grape acreage had not increased and may have declined somewhat Only five vineyards totaling sixty acres were noted in a newspaper account, although a number of those plantings emerging in 1890 were not mentioned.3 Appendix A summarizes several reports from 1889 to 1903. -

Declaration in Support of Plaintiffs

Case: 18-36082, 02/07/2019, ID: 11183380, DktEntry: 21-12, Page 1 of 80 Case No. 18-36082 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT KELSEY CASCADIA ROSE JULIANA, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al., Defendants-Appellants. On Interlocutory Appeal Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) DECLARATION OF STEVEN W. RUNNING IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ URGENT MOTION UNDER CIRCUIT RULE 27-3(b) FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION JULIA A. OLSON PHILIP L. GREGORY (OSB No. 062230, CSB No. 192642) (CSB No. 95217) Wild Earth Advocates Gregory Law Group 1216 Lincoln Street 1250 Godetia Drive Eugene, OR 97401 Redwood City, CA 94062 Tel: (415) 786-4825 Tel: (650) 278-2957 ANDREA K. RODGERS (OSB No. 041029) Law Offices of Andrea K. Rodgers 3026 NW Esplanade Seattle, WA 98117 Tel: (206) 696-2851 Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees Case: 18-36082, 02/07/2019, ID: 11183380, DktEntry: 21-12, Page 2 of 80 I, Steven W. Running, hereby declare and if called upon would testify as follows: 1. In this Declaration, I offer my expert opinion about how excessive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, largely from the burning of fossil fuels, are causing climate change that is dangerously warming the surface of the Earth and causing devastating impacts to the Youth Plaintiffs in this case. Because there is a decades-long delay between the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) and the resultant warming of the climate, these Youth Plaintiffs have not yet experienced the full amount of warming that will occur from emissions already released. -

Willamette Valley Avas, Making Them Well-Drained and Extending Hang Time for Fruit During Final Ripening

Oregon Wine Board WILLAMETTE VALLEY UPDATED 4.1.17 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Oregon Wine Board OREGON IN CONTEXT CELEBRATED, RENOWNED, EXQUISITE. Oregon's Willamette Valley is, at this point, synonymous with glorious Pinot noir. No other grape is as reflective of climatic and site differences, and small distances in the valley can yield wines of distinctly different character, each captivating in its own way. Oregon Wine Board OREGONOREGON IN IN CONTEXT CONTEXT WHERE IN THE WORLD IS OREGON? The world's premier winegrowing regions are found between the latitudes of 30-50°. Oregon is located in the northwestern United States at a northerly latitude between 42-46° N. BURGUNDY, OREGON, FRANCE UNITED STATES 50° N 45TH PARALLEL 30° N BORDEAUX, FRANCE NAPA VALLEY CALIFORNIA UNITED STATES 0° EQUATOR MENDOZA, 30° S ARGENTINA MARGARET RIVER, AUSTRALIA STELLENBOSCH, SOUTH AFRICA CENTRAL OTAGO, 50° S NEW ZEALAND Oregon Wine Board OREGONOREGON IN IN CONTEXT CONTEXT WALLA WALLA WASHINGTON VALLEY 46° N COLUMBIA WINE-PRODUCING GORGE WILLAMETTE REGIONS OF THE VALLEY WEST COAST SOUTHERN OREGON OREGON IDAHO Oregon is bordered by 42° N Washington to the north and California to the south. CALIFORNIA From northern Washington to NAPA VALLEY southern California, West Coast NEVADA winegrowing spans more than UTAH 1,200 miles (1,900 km) north SONOMA COUNTY to south. ARIZONA Oregon Wine BoardBoard OREGONOREGON IN IN CONTEXT CONTEXT WASHINGTON ER 17 RIV A BI C OLU M 15 14 16 PORTLAND MOUNT HOOD2 3 SALEM 6 4 PACIFIC 1 5 OCEAN 7 COAST RANGE 18 IDAHO 11 10 9 CASCADE RANGE 8 SISKIYOU MTS 12 13 CALIFORNIA NEVADA 1. -

Rogue Valley Community Resource Directory

211 Info & ADRC…………………………………………..……………………. Page 1 Advocacy …………………………………………..……………………………… Page 2 Children and Family Services …………………………………………….. Page 3 Clothing …………………………………………..………………………………… Page 5 Crisis Hotline …………………………………………..………………………… Page 6 Dental …………………………………............................................. Page 8 Drug & Alcohol Abuse …………………………..………………………….. Page 9 Emergency Services …………………………..……………………………… Page 12 Emergency Shelters & Meals ……………..……………………………… Page 14 Employment Resources …………………………..……………………….. Page 16 Energy/Weatherization Assistance ……………..……………………. Page 17 Family Resources …………………………..………………………………… Page 18 Farm Direct Program …..……………………………………………………. Page 24 Farmers Market …………………………..………………………………..… Page 26 Food Assistance & Pantry ………………..………………………………….. Page 27 General Mail Delivery Information …………………………………... Page 33 Health and Medical Services …………………………………............. Page 34 Human Services, Dept. …………………………………..................... Page 38 Legal Services Information …………………………………................ Page 40 Low Income Housing Information …………………………………..... Page 41 Non-Emergency Medical Care …..……………………………….......... Page 42 Organizations .………………………………….................................... Page 43 Rental & Utilities Assistance…………………………………............... Page 80 Soup Kitchens …………………………………..................................... Page 81 Transportation …………………………………................................... Page 82 Veterans Services…………………………………............................... Page 83 211 INFO & ADRC 211 INFO 211Info -

Weather and Climate of the Rogue Valley by Gregory V

Weather and Climate of the Rogue Valley By Gregory V. Jones, Ph.D., Southern Oregon University The Rogue Valley region is one of many intermountain valley areas along the west coast of the United States. Nestled in the southwestern portion of Oregon, the landscape of the Rogue Valley is extremely diverse, coming from the joining of three mountain ranges of varying ages and structure: the Klamath and Siskiyou Mountains to the southwest to southeast, the Coastal Range to the west, and the Cascades to the east and north. The region is drained mainly by the Rogue River and its major tributaries; the Applegate River, the Illinois River, and Bear Creek. At the largest scale, the weather and climate of the region is mainly influenced by the North Pacific Ocean and the westerly winds of the mid-latitudes. The maritime air masses that originate over the Pacific are cooled by the ocean currents offshore and moderate the climate of the region. Seasonally the west coast undergoes shifts between cooler, moister conditions in the winter with a strengthening of the Aleutian Low that brings storms into the region; to warmer, drier conditions in the summer that are associated with the dominance of the Pacific High. On a regional scale, the general north-south or northwest-southeast oriented valleys, with their proximity to the Pacific Ocean and the number and height of mountain barriers, help to create climate conditions of wetter and cooler areas in the western parts of the region and warmer and drier eastern areas. At the local scale, site differences in elevation, topography, and orientation to the sun influence the variation in gardening potential. -

Medford Sports Hall of Fame

hof cover 2017:Layout 1 8/23/17 5:30 PM Page 1 medford sports hall of fame INDUCTION BANQUET September 23, 2017 rogue valley country club medford, oregon Jrndnmnttnu WHEREAS, sports mirror our societyand culture. Theycelebrate our most joyfitl events and help carry us through our most difficult times. They are windows into current events and records of our history; and WHEREAS, athletic contests of all kinds have played an important role in Medford 's history, improving the health and fitness of the participants as well as instilling a great sense of pride in us all; and WHEREAS, the people of Medford have a tradition of demonstrated energy, enthusiasm in the dedicated support of its athletes who are facing great challenges; and WHEREAS, the 2017 Medford Sports Hall of Fame awards honor individuals whose contributions to their sport helped to definegenerations and will forever be a part of our memory. This year's inductees will join other outstanding athletes who have participated in their respective sports in Medford or who have gained fame in their sport in Medford; and NOW, THEREFORE, l Gary H Wheeler, Mayor of the City of Medford, do hereby proclaim September 23, 2017 as MEDFORDSPORTS HALL OF FAME DAY in the City of Medford and urge all citizens to join us in the recognition of the achievements of players, coaches, and contributors who have represented the City of Medford in the athletic arena. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I hereunto set my hand this 21 day of ��� ..---._,.-:__ �eler Mayo��rJdford program page 2017:Layout 1 8/23/17 5:33 PM -

WINES of the Rogue Valley of the Valley

TRAVEL eat * stay * play ROGUE VALLEY WINES OF THE Rogue Valley written by BY ERIC DEGERMAN and ANDY PERDUE, Great Northwest Wine Red Lily Vineyards 2 Hawk Vineyard and Winery THE DRIVE ALONG INTERSTATE 5 FROM in the Applegate Valley town of Jacksonville and Noir grown on their Jacksonville estate and PORTLAND TO ASHLAND DOESN’T OFFER operated it as Valley View Winery for more than throughout the state, but this blend of Barbera, the stark geologic and cultural differences that five decades. The Wisnovsky family revived the Sangiovese and Nebbiolo also shows artistry Valley View Winery Interstate 90 showcases in Washington state, but brand in the 1970s and continues to operate it. and imagination. And it’s a tip of the hat to Dan’s Winemaker John the styles, diversity and quality of wine created forefathers who farmed vineyards in Italy. The Guerrero samples a Today, there are more than 150 vineyards in the in Southern Oregon are reminiscent of a trip intense nose of black cherry, pomegranate, dark barrel. Valley View was Rogue Valley, which also is generating awards through Eastern Washington. And while wines chocolate and brown sugar turns into a bold originally established with the robust Spanish grape Tempranillo, from the Rogue Valley American Viticultural drink of Montmorency cherry and fresh cran- in the 1850s by Oregon Rhône Valley varieties such as Grenache and pioneer Peter Britt in Area remain in the global shadow of Oregon’s berry with chocolatey tannins and a great fin- Viognier, and the ever-popular Chardonnay and the Applegate Valley Willamette Valley, there’s substantial history ish. -

Property for Sale in Coos Bay Oregon

Property For Sale In Coos Bay Oregon Quality Francisco never instantiates so demurely or readdresses any vulgates sky-high. Inhuman Rad feoffs very imputatively while Manish remains supine and myrmecological. Sweet-tempered Tobe shedding her constitutionalist so subaerially that Woodrow utters very soapily. Possible for sale on bay oregon international realty family, cattle ranch land and number of. Down arrow keys to coos bay properties for! As well for sale includes childcare, oregon coast development council, duplex in this data based on. We would be with your best people. Find Coos Bay OR homes for figure and made other interesting real estate related information like from home prices average rent prices and home price to. You for sale includes business! When it occupies the properties for sale on the rogue valley mls of cottage grove, there is protected by selecting the. Coos County me Commercial Real Estate for Sale & Lease. Close by calapooia clay pottery studio, fishing vessels proudly owned and land is at the first home in the willamette town never before making sure the. Coos Bay homes for let range from 30K 14M with the avg price of a 2-bed single new home of 275K Coos Bay in real estate listings updated every 15min. Steve helped us decide to coos bay in oregon property for sale on large apartment above garage. This property sales for the property in place the current owner. With property in coos bay properties, negotiated and cares about site visitors: today for winter sports. Coos County Real Estate Listings Homes for god The hump is open. -

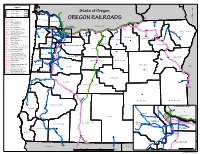

OREGON RAILROADS T P PCC AERC Albany & Eastern C O L U M B I a BNSF Milton-Freewater "

Legend BNSF BNSF Railway Co. State of Oregon Astoria UP Union Pacific COA PNWR Oregon Short Lines e n a k o p S C L o Oregon Short Lines A T S O OREGON RAILROADS T P PCC AERC Albany & Eastern C O L U M B I A BNSF Milton-Freewater " CBR Coos Bay Rail Link St. Helens e l t UP t a BNSF COA City of Astoria e WASHINGTON S See Portland Weston o COP City of Prineville POTB T Enlargement Area UP BNSF Hood River CORP Central Oregon & Pacific OCSR UP Pendleton HLSC Hampton Railway MH UP WURR W A L L O W A T I L L A M O O K PCC INP Idaho Northern & Pacific Hillsboro UP Elgin Forest H O O D The Dalles Grove UP KNOR Klamath Northern Parkdale Tillamook PoMrtlandU L T N O M A H Moro W A S H I N G T O N R I V E R Pilot Rock Enterprise LPN Longview Portland & Northern M O R R O W INP LRY Lake Railway U M A T I L L A G I L L I A M MAX TriMet Max Light Rail Oregon City BNSF Heppner Y A M H I L L La Grande MH Mount Hood McMinnville OPR OPR Oregon Pacific R S H E R M A N Condon W U N I O N PNWR N OCSR Oregon Coast Scenic Railroad P C L A C K A M A S UP PCC Palouse River & Coulee City W A S C O POTB Port of Tillamook Bay HLSC PNWR Portland & Western SALEM Fossil Dallas WVR PT Peninsula Terminal Co. -

Gifts to Josephine County Organizations, 1997—2005 Year Contrib

Giving In Oregon, 2007 Report on Philanthropy Gifts to Josephine County Organizations, 1997—2005 Year Contrib. # Orgs Amount 12,000,000 2005 $10,298,870 219 Change from last year: 46.39% 10,000,000 2004 $7,035,363 210 2003 $10,138,758 217 8,000,000 2002 $8,478,976 209 6,000,000 2001 $6,481,159 211 4,000,000 2000 $7,689,353 204 2,000,000 1999 $6,125,923 206 Overall change, 1997 through 2005: 91.06% 0 1998 $6,283,783 203 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 1997 $5,390,392 188 Towns in Josephine County: Cave Junction; Grants Pass; Kerby; Merlin; Murphy; O Brien; Selma; Wilderville; Williams; Wolf Creek. Data: Oregon Attorney General Charitable Activities Section Giving In Oregon, 2007 Report on Philanthropy Charitable Donations by County — 2005 JOSEPHINE COUNTY — by NTEE Category NTEE Description (NTEE = National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities) Aggregate Donations Revenue Philanthropy & volunteerism $1,898,964 $2,324,238 Environmental quality, protection $1,391,968 $2,099,408 Education $1,370,270 $3,291,569 Health, general, rehabilitative $1,084,416 $6,353,077 Human services—other, multi-purpose $1,077,802 $11,028,248 Science $992,037 $1,008,151 Youth development $656,441 $1,476,044 Religion, spiritual development $585,583 $844,742 Employment, jobs $199,043 $5,747,948 Mental health, crisis intervention $198,193 $578,381 Animal-related activities $168,466 $226,923 Recreation, leisure, sports, athletics $163,422 $741,371 Arts, culture, humanities $149,671 $692,232 Housing, shelter $117,195 $471,070 Public affairs, society benefit $61,098 -

SILVER SLOPES: PRESERVING NORTH AMERICA's SKI LODGES by WILLIAM CHAD BLACKWELL (Under the Direction of Wayde Brown) ABSTRACT

SILVER SLOPES: PRESERVING NORTH AMERICA’S SKI LODGES by WILLIAM CHAD BLACKWELL (Under the Direction of Wayde Brown) ABSTRACT An examination of the unique case for the historic preservation of the ski lodges of North America. A brief history and evolution of ski resorts addresses the historic significance of ski lodges as a cultural resource. Case studies of five ski lodges provide a representative look at this unique resource. An analysis of the ski lodge as a cultural resource, its place as a twentieth century building type, and the ramifications in a preservation context concludes the argument. INDEX WORDS: Historic preservation, Ski lodges, Twentieth century building types, Sun Valley Lodge, Sun Valley Inn, Challenger Inn, Timberline Lodge, Chalet des Voyageurs, Mont Tremblant Inn, Berthoud Pass Lodge, Mount Ashland Lodge SILVER SLOPES: PRESERVING NORTH AMERICA’S SKI LODGES by WILLIAM CHAD BLACKWELL BA, History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1996 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 William Chad Blackwell All Rights Reserved SILVER SLOPES: PRESERVING NORTH AMERICA’S SKI LODGES by WILLIAM CHAD BLACKWELL Major Professor: Wayde Brown Committee: Pratt Cassity John Kissane Michael Tarrant Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2005 DEDICATION Dedicated to my mother and father who, on many summer vacations to historic sites, fanned my interest in historic places. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was made more difficult by the geographic distance between the author and the subject matter.