Caroline Hao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 TOYOTA US Figure Skating Championships

2020 TOYOTA U.S. FIGURE SKATING CHAMPIONSHIPS OFFICIAL EVENT PROGRAM EVENT CHAMPIONSHIPS OFFICIAL FIGURE SKATING U.S. TOYOTA 2020 Highlander and Camry Hey, Good Looking There they go again. Highlander and Camry. Turning heads wherever they go. The asphalt is their runway, as these two beauties bring sexy back to the cul-de-sac. But then again, some things are always fashionable. Let’s Go Places. Some vehicles prototypes. All models shown with options. ©2019 Toyota Motor Sales, U.S.A., Inc. 193440-2020 US Championships Program Cover.indd 1 1/1/20 1:33 PM 119901_07417P_FigureSkating_MMLGP_Style_7875x10375_em1_w1a.indd 1 5/10/19 3:01 PM SAATCHI & SAATCHI LOS ANGELES • 3501 SEPULVEDA BLVD. • TORRANCE, CA • 90505 • 310 - 214 - 6000 SIZE: Bleed: 8.625" x 11.125" Trim: 7.875" x 10.375" Live: 7.375" x 9.875" Mechanical is 100% of final BY DATE W/C DATE BY DATE W/C DATE No. of Colors: 4C Type prints: Gutter: LS: Output is 100% of final Project Manager Diversity Review Panel Print Producer Assist. Account Executive CLIENT: TMNA EXECUTIVE CREATIVE DIRECTORS: Studio Manager CREATIVE DIRECTOR: M. D’Avignon Account Executive JOB TITLE: U.S. Figure Skating Resize of MMLGP “Style” Ad Production Director ASSC. CREATIVE DIRECTORS: Account Supervisor PRODUCT CODE: BRA 100000 Art Buyer COPYWRITER: Management Director Proofreading AD UNIT: 4CPB ART DIRECTOR: CLIENT Art Director TRACKING NO: 07417 P PRINT PRODUCER: A. LaDuke Ad Mgr./Administrator ART PRODUCER: •Chief Creative Officer PRODUCTION DATE: May 2019 National Ad Mgr. STUDIO ARTIST: V. Lee •Exec. Creative Director VOG MECHANICAL NUMBER: ______________ PROJECT MANAGER: A. -

Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding

Moments in Time by Frank C. Clifford The ATTAck on nAncy kerrigAn: JAnuAry 6, 1994; 2:35 p.m. eST; DeTroiT, michigAn t was an extraordinary, soap opera–style plot that was But the attempts of the attacker (Shane Stant) to fracture Ker- hatched to clear the path to victory at the February 1994 rigan’s right leg failed. He fed, his planned exit route was I Winter Olympics for gutsy, troubled ice skater Tonya Har- locked, and the getaway driver was at a different location from ding. But it was ill-conceived and poorly planned, and would the one that had been arranged. Several days later, Gillooly earn a spot in the “tabloid hall of fame” as one of the most was overheard talking about the attack, and notes of the game scandalous sporting events in history. plan in his (and allegedly Tonya’s) handwriting were found. The knee-bashing attack on Nancy Kerrigan led to all fve The attack put Kerrigan out of action for a short while, protagonists receiving jail time or criminal records. And amid but she was deemed ft to compete at the Olympic event (held a media frestorm, it put the sport of fgure skating frmly on February 23–25), for which Harding also qualifed. By that the map — resulting in a staggering 126 million viewers in point, most details of the bungled plot and its hapless con- the United States tuning in to an Olympic “Cold War” be- spirators had been unearthed by the FBI, with Gillooly and tween Harding and Kerrigan that was as bitter and hard as the Harding attempting to implicate one another. -

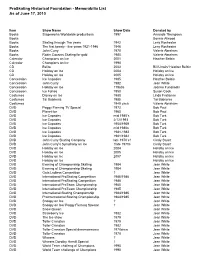

Memorabilia List As of 6-17-10

ProSkating Historical Foundation - Memorabilia List As of June 17, 2010 Item Show Name Show Date Donated by Books Stageworks Worldwide productions 1997 Amanda Thompson Books Bonnie Atwood Books Skating through The years 1942 Leny Rochester Books The first twenty - five years 1921-1946 1946 Leny Rochester Books John Curry 1978 Valerie Abraham Books Robin Cousins Skating for gold 1980 Valerie Abraham Calendar Champions on Ice 2001 Heather Belbin Calendar Champions on Ice 1998 CD Belita 2003 Bill Unwin/ Heather Belbin CD Holiday on Ice 2004 Holiday on Ice CD Holiday on Ice 2005 Holiday on Ice Concession Ice Capades 1985 Heather Belbin Concession John Curry 1982 Jean White Concession Holiday on Ice ?1960s Joanne Funakoshi Concession Ice Follies 1950 Susan Cook Costumes Disney on Ice 1980 Linda Fratianne Costumes Tai Babilonia 1985 Tai Babilonia Costumes 1949 circa Valerie Abraham DVD Peggy Fleming TV Special 1972 Bob Paul DVD Planet Ice 1960 Bob Paul DVD Ice Capades mid 1980’s Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 2/12/1993 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1958/1959 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades mid 1980s Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1981-1982 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1981/1982 Bob Turk DVD John Curry Skating Company late 1970’s? Cindy Stuart DVD John Curry’s Symphony on Ice ?late 1970s Cindy Stuart DVD Holiday on Ice 2004 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice 2005 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice 2007 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice Holiday on Ice DVD Evening of Championship Skating 1984 Jean White DVD Evening of Championship Skating 1984 Jean White DVD Gala Ladiess Competition -

America's Stars on Ice Shine for Groups in 2019!

America’s Stars on Ice Shine for Groups in 2019! See the best of American figure skating past, present and future in the all-new Stars on Ice presented by Musselman’s tour. Olympic Medalists NATHAN CHEN*, MAIA & ALEX SHIBUTANI, ASHLEY WAGNER, JASON BROWN*, MIRAI NAGASU, JEREMY ABBOTT and BRADIE TENNELL will join Olympic Gold Medalists MERYL DAVIS & CHARLIE WHITE, plus World Medalists MADISON HUBBELL & ZACH DONOHUE and U.S Medalist VINCENT ZHOU in this true red, white and blue celebration on ice! Showcased at each performance are thrilling solo numbers, along with show-stopping ensemble pieces — a Stars on Ice signature! Gather your group and enjoy a night to remember. Larger groups may qualify to receive additional autographed items and experiences that are exclusive to Stars on Ice. *Not appearing in all cities. 2019 GROUP SALES – SPECIAL OFFERS 10+ TICKETS Exclusive $10 discount per ticket (excludes on ice seats). 20-49 TICKETS Discount plus 2 free tickets and 1 cast-signed poster. 50-99 TICKETS Discount plus 4 free tickets, admission to pre-show warm-ups and our popular Icebreaker session featuring 2 cast members, and 3 cast-signed posters. 100+ TICKETS Discount plus 6 free tickets, admission to pre-show warm-ups and our popular Icebreaker session featuring 2 cast members, “Welcome” announcement before the show, 3 cast-signed posters, autographed Stars on Ice card for each member of the group, and a skater visit. starsonice.com DATE AND CAST SUBJECT TO CHANGE. STARS ON ICE AND LOGO ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF INTERNATIONAL MERCHANDISING COMPANY, LLC. © 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. -

Champions of the United States

U.S. FIGURE SKATING DIRECTORY CHAMPIONS OF THE UNITED STATES LADIES 1960 Carol Heiss, The SC of New York 2018 Nathan Chen, Salt Lake Figure Skating 1959 Carol Heiss, The SC of New York 2017 Nathan Chen, Salt Lake Figure Skating 2021 Bradie Tennell, Skokie Valley SC 1958 Carol Heiss, The SC of New York 2016 Adam Rippon, The SC of New York 2020 Alysa Liu, St. Moritz ISC 1957 Carol Heiss, The SC of New York 2015 Jason Brown, Skokie Valley SC 2019 Alysa Liu, St. Moritz ISC 1956 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 2014 Jeremy Abbott, Detroit SC 2018 Bradie Tennell, Skokie Valley SC 2013 Max Aaron, Broadmoor SC 2017 Karen Chen, Peninsula SC 1955 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 1954 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 2012 Jeremy Abbott, Detroit SC 2016 Gracie Gold, Wagon Wheel FSC 2011 Ryan Bradley, Broadmoor SC 1953 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 2015 Ashley Wagner, SC of Wilmington 2010 Jeremy Abbott, Detroit SC 1952 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 2014 Gracie Gold, Wagon Wheel FSC 2009 Jeremy Abbott, Broadmoor SC 1951 Sonya Klopfer, Junior SC of New York 2013 Ashley Wagner, SC of Wilmington 2008 Evan Lysacek, DuPage FSC 1950 Yvonne Sherman, The SC of New York 2012 Ashley Wagner, SC of Wilmington 2007 Evan Lysacek, DuPage FSC 1949 Yvonne Sherman, The SC of New York 2011 Alissa Czisny, Detroit SC 2006 Johnny Weir, The SC of New York 1948 Gretchen Merrill, The SC of Boston 2010 Rachael Flatt, Broadmoor SC 2005 Johnny Weir, The SC of New York 2009 Alissa Czisny, Detroit SC 1947 Gretchen Merrill, The SC of Boston 2004 Johnny Weir, The SC of New York 2008 Mirai Nagasu, Pasadena FSC 1946 Gretchen Merrill, The SC of Boston 2003 Michael Weiss, Washington FSC 2007 Kimmie Meissner, Univ. -

The Woman Who's Teaching the NHL How to Skate - Pacific Standard

The Woman Who's Teaching the NHL How to Skate - Pacific Standard facebook linkedin instagram twitter MAGAZINE NEWSLETTER SUBSCRIBE SUBSCRIBE NEWS ECONOMICS EDUCATION ENVIRONMENT SOCIAL JUSTICE SOCIAL JUSTICE THE WOMAN WHO'S TEACHING THE NHL HOW TO SKATE As one of the only female coaches in all of the four major professional sports, Barb Underhill is carving out an important legacy, both on and off the ice. SAM RICHES · MAR 14, 2014 3 facebolinkediinstagrtwitter print SHARES https://psmag.com/social-justice/woman-whos-teaching-nhl-skate-76542[7/11/2017 3:54:45 PM] The Woman Who's Teaching the NHL How to Skate - Pacific Standard Barb Underhill works with Jerry D'Amigo of the Torono Maple Leafs. (Photo: Sam Riches) At the Toronto Maple Leafs practice facility Barb Underhill carves long, elegant rifts into a clean sheet of ice. It’s early on a Tuesday morning, and bright, white light drifts down from the arena roof, giving everything a hard glow. Jerry D’Amigo, a forward with the Leafs, skates next to her. The arena is empty otherwise and the sound of their steel blades cutting into the surface fills the still air. “Keep your feet moving,” she tells him. “Use your power.” Her short blonde hair curls back in a wave as she dances up and down the ice, alongside the Toronto forward. At 5'11", D’Amigo is not exceptionally tall, but he towers above Underhill, who barely reaches his shoulders. A strong skater by NHL standards, D’Amigo suddenly looks stiff moving next to her. Underhill taps her stick against the ice, encouraging the 22-year-old, who works through a drill at the center of the rink, his eyes narrowed in concentration. -

ANNOUNCEMENT White Nights International Adult Figure Skating Competition St.Petersburg, Russia, 24-26 May, 2013

САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГСКАЯ РЕГИОНАЛЬНАЯ ОБЩЕСТВЕННАЯ ФИЗКУЛЬТУРНО-СПОРТИВНАЯ ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯ «ЛИГА ЛЮБИТЕЛЕЙ ФИГУРНОГО КАТАНИЯ» LEAGUE OF FANS OF FIGURE SKATING, SAINT-PETERSBURG, RUSSIA ОГРН/Main State Registration Number 1107800009316 International Adult Figure Skating Competition White Nights for Men, Ladies, Pairs, Ice Dance and Synchronized Skating organized by the League of Fans of Figure Skating Saint-Petersburg, Russia May 24 – May 26, 2013 ANNOUNCEMENT White Nights International Adult Figure Skating Competition St.Petersburg, Russia, 24-26 May, 2013 1. GENERAL The International Adult Figure Skating Competition White Nights 2013 will be conducted in accordance with the ISU Constitution and General Regulations 2012, the ISU Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pairs Skating and Ice Dance 2012, the Special Regulations & Technical Rules Synchronized Skating 2012, as well as all pertinent ISU Communications, and this Announcement. If there is a conflict between pertinent ISU Regulations or Communications and provisions set forth in this Announcement, the provisions in the Announcement govern. International Adult Figure Skating Competition White Nights 2013 will take place in the historic center of the world of figure skating, the city where was held the first ISU World Championships in 1896. Participation in the International Adult Figure Skating Competition White Nights 2013 is open to all skaters who belong to an ISU Member, as per Rule 107, paragraph 9 and 12, Rule 109, paragraph 1, and qualify with regard to eligibility, according to Rule 102, provided their ages fall within the limits specified in this Announcement and they meet the participation requirements. In the International Adult Figure Skating Competition White Nights 2013 only single skaters may compete who have reached at least the age of eighteen (18) before July 1st, preceding the event but have not reached the age of seventy-nine (79) before July 1st, preceding the competition. -

Nancy Pluta Resume

Nancy Pluta , Choreographer 823 E. Paradise Lane [email protected] Phoenix , AZ. 85022 (480)-200-9053 cell (602) 938-4441 home “I have the ability to communicate artistic ideas, to all different styles of artistry” Choreography 2008 Fire Spinning Choreographer PSA Certified Choreography and Style Rating 2007-Present Director and Choreographer, Coyotes Ice Ensemble, theater on ice international/national competition team 2007 Chorus Choreographer, “Sterren Dansen Op Het Jis”, live T.V.show for Holiday On Ice, Eyeworks, and S.B.S., Hilversum, Holland Director and choreographer for S.B.S. & Eyeworks, Private Industrial Broadcasting and Commercial show, Hilversum, Holland Skating Club of Phoenix Memorial Trophy awarded for highest choreography points for Intermediate Short Program, USFS 2006 Director and Choreographer of “Holiday On Ice, Under The Desert The Sky” National television broadcast, hosted by Nancy Kerrigan and starring Brian Orser Assistant Choreographer, Coyotes Ice Ensemble, theater on ice international/national competition team Artistic Award for Choreography, Juvenile Artistic Program, Orange County, CA, USFS 2005-Present Choreographer, USFSA Freestyle programs 2005 Assistant Choreographer, “Snoopy Summer Vacation”, Cedar Point, Sandusky, Ohio Cast Change-over Choreographer, Voyager of the Seas, Willy Bietak Productions 2004 Cast Change-over Choreographer, Voyager & Navigator of the Seas, Willy Bietak Productions 2003 Associate Choreographer, Disney On Ice, “Monsters Inc.” production and Choreographer of the television -

Iran Tests Anti-Ship Missile As Powers Press N-Pullback

skiing THE FIRST ENGLISH LANGUAGE DAILY IN FREE KUWAIT markets Page 14 Established in 1977 / www.arabtimesonline.com Page 9 SUNDAY, JANUARY 17, 2021 / JUMADA AL THANI 4, 1442 AH emergency number 112 NO. 17589 16 PAGES 150 FILS U.S. NAMES BAHRAIN, UAE MAJOR SECURITY PARTNERS Opinion Iran tests anti-ship missile Ibn Khaldun: Nations fall if rulers lack top advisors as Powers press N-pullback By Ahmed Al-Jarallah mercial nor financial interests. In Editor-in-Chief, the Arab Times fact, these leaders brag about such choices due to their conviction that CHOOSING good advisors is one of those advisors will paint the actual the main ingredients of state admin- image of the country to them and rely istration and growth. That is what an on the demands of the people. Arab scholar of Islam, social scien- This kind of approach is not limit- tist, philosopher and historian Abdul ed to running a country only, but also Rahman Ibn Khaldun had written in parties and companies. his famous book “Al-Muqaddimah” Currently, some Arabian Gulf (The Introduction) - the recipe for countries are suffering from several the fall of states, almost six centuries crises economically and politically. ago. Unfortunately, the plans put in place “Poor selection of the aides (advi- to solve them are extemporaneous, sors) by the ruler is an outright sui- provocative and unrehearsed. This cide attempt for the state because definitely indicates that the crises they blindfold the ruler. Therefore, will escalate if the political leaders do justice becomes illusive”. In addition, not change the approach, not only in “the state reaches a stage of collapse terms of choosing advisors, but also when it is unable to meet and face the on how they deal with cases and files challenges it encounters”. -

Las Vegas, Nevada

2021 Toyota U.S. Figure Skating Championships January 11-21, 2021 Las Vegas | The Orleans Arena Media Information and Story Ideas The U.S. Figure Skating Championships, held annually since 1914, is the nation’s most prestigious figure skating event. The competition crowns U.S. champions in ladies, men’s, pairs and ice dance at the senior and junior levels. The 2021 U.S. Championships will serve as the final qualifying event prior to selecting and announcing the U.S. World Figure Skating Team that will represent Team USA at the ISU World Figure Skating Championships in Stockholm. The marquee event was relocated from San Jose, California, to Las Vegas late in the fall due to COVID-19 considerations. San Jose meanwhile was awarded the 2023 Toyota U.S. Championships, marking the fourth time that the city will host the event. Competition and practice for the junior and Championship competitions will be held at The Orleans Arena in Las Vegas. The event will take place in a bubble format with no spectators. Las Vegas, Nevada This is the first time the U.S. Championships will be held in Las Vegas. The entertainment capital of the world most recently hosted 2020 Guaranteed Rate Skate America and 2019 Skate America presented by American Cruise Lines. The Orleans Arena The Orleans Arena is one of the nation’s leading mid-size arenas. It is located at The Orleans Hotel and Casino and is operated by Coast Casinos, a subsidiary of Boyd Gaming Corporation. The arena is the home to the Vegas Rollers of World Team Tennis since 2019, and plays host to concerts, sporting events and NCAA Tournaments. -

Welcome to the “Barbara Ann Scott: Come Skate with Me” Exhibit Podcast Presented by the City of Ottawa Archives

Welcome to the “Barbara Ann Scott: Come Skate with me” exhibit podcast presented by the city of Ottawa archives. In the podcast, City Archivist Paul Henry interviews Barbara Ann Scott at her home in Florida, and Educational Programming Officer Olga Zeale interviews Paul Henry and Elizabeth Manley in Ottawa. PH: My name is Paul Henry, I am City Archivist for the City of Ottawa. OZ: Why was it important for the City of Ottawa Archives to acquire Barbara Ann Scott’s collection? PH: Uh, well the mandate of the City of Ottawa Archives is to document the corporation of the City of Ottawa as well as serve as a repository for records that would otherwise be lost to history; records that in particular tell the story of the individual contributions of notable citizens, organizations, businesses, community organizations, that have contributed to the fabric of Ottawa and which tell, essentially, the story of the gap between what the City does and what our known history of an area is. So, the private records really flush out and make interesting a story of Ottawa beyond its role as a nation‟s capital. The Barbara Ann Scott collection fulfills that in many ways. Barbara is our most decorated citizen, our most decorated Olympic athlete, and if you think back to those days in „47 and „48 when we had, and gave Barbara the key to the city and had events and parades in her honour. The number of people that came out in those days to celebrate her accomplishments was certainly something, and in many ways, the city, in some way belongs to Barbara. -

ISU Junior Grand Prix Final 2019/20 Day Two

December 6, 2019 Turin, Italy ISU Junior Grand Prix Final 2019/20 Day Two Kazakova/Reviya (GEO) capture Junior Rhythm Dance Maria Kazakova/Georgy Reviya of Georgia captured the Rhythm Dance, edging the hot favorites Avonley Nguyen/Vadym Kolesnik (USA) by just 0.04 points. Russia’s Elizaveta Shanaeva/Devid Naryzhnyy follow in third place. Dancing to Quickstep and Foxtrot set to “Beautiful the Carole King” and “Dream a Little Dream of Me”, Kazakova/Reviya produced level-four twizzles and a level-four stationary lift. The Tea Time Foxtrot pattern and the midline step sequence were rated a level three. The JGP Zagreb Champions achieved a new personal best score with 68.76 points. “It wasn’t easy today, we are very happy with our marks but not so happy with the skate. We had a few small issues with the twizzles which didn’t go quite as we needed them to, and on a few transitions we lost speed, but we got back into the program quite quickly,” Reviya observed. Nguyen/Kolesnik put out an upbeat dance to “Aladdin”, completing fast twizzles and steps and a rotational lift. The JGP Lake Placid Champions collected a level four for the twizzles and the lift while the midline step sequence and the first Tea Time Foxtrot sequence garnered a level two. The JGP Gdansk Champions earned 68.72 points. “We just want to do as well as we can and keep im- proving our programs. We hope the judges like what they see and we hope the people who see us feel something from our skating,” Ngyuen noted.