Should You Fear the Pizzly Bear? - Nytimes.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2016 Annual Report

WASHINGTON GRAY WOLF CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT 2016 ANNUAL REPORT A cooperative effort by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Confederated Colville Tribes, Spokane Tribe of Indians, USDA-APHIS Wildlife Services, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Photo: WDFW This report presents information on the status, distribution, and management of wolves in the State of Washington from January 1, 2016 through December 31, 2016. This report may be copied and distributed as needed. Suggested Citation: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Confederated Colville Tribes, Spokane Tribe of Indians, USDA-APHIS Wildlife Services, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Washington Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2016 Annual Report. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Colville, WA, USA. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Gray wolves (Canis lupus) were classified as an endangered species in Washington under the provisions of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1973. In 2011, wolves in the eastern third of Washington were removed from federal protections under the ESA. Wolves in the western two- thirds of Washington continue to be protected under the ESA and are classified as an endangered species under federal law. In December 2011, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) Commission formally adopted the Wolf Conservation and Management Plan to guide recovery and management of gray wolves as they naturally recolonize the State of Washington. At present, wolves are classified as an endangered species under state law (WAC 232-12-014) throughout Washington regardless of federal status. Washington is composed of three recovery areas which include Eastern Washington, the Northern Cascades, and the Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast. -

Northeastern Coyote/Coywolf Taxonomy and Admixture: a Meta-Analysis

Way and Lynn Northeastern coyote taxonomy Copyright © 2016 by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISSN 1478-2677 Synthesis Northeastern coyote/coywolf taxonomy and admixture: A meta-analysis Jonathan G. Way1* and William S. Lynn2 1 Eastern Coyote Research, 89 Ebenezer Road, Osterville, MA 02655, USA. Email [email protected] 2 Marsh Institute, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610, USA. Email [email protected] * Correspondence author Keywords: Canis latrans, Canis lycaon, Canis lupus, Canis oriens, cladogamy, coyote, coywolf, eastern coyote, eastern wolf, hybridisation, meta-analysis, northeastern coyote, wolf. Abstract A flurry of recent papers have attempted to taxonomically characterise eastern canids, mainly grey wolves Canis lupus, eastern wolves Canis lycaon or Canis lupus lycaon and northeastern coyotes or coywolves Canis latrans, Canis latrans var. or Canis latrans x C. lycaon, in northeastern North America. In this paper, we performed a meta-analysis on northeastern coyote taxonomy by comparing results across studies to synthesise what is known about genetic admixture and taxonomy of this animal. Hybridisation or cladogamy (the crossing between any given clades) be- tween coyotes, wolves and domestic dogs created the northeastern coyote, but the animal now has little genetic in- put from its parental species across the majority of its northeastern North American (e.g. the New England states) range except in areas where they overlap, such as southeastern Canada, Ohio and Pennsylvania, and the mid- Atlantic area. The northeastern coyote has roughly 60% genetic influence from coyote, 30% wolf and 10% domestic dog Canis lupus familiaris or Canis familiaris. There is still disagreement about the amount of eastern wolf versus grey wolf in its genome, and additional SNP genotyping needs to sample known eastern wolves from Algonquin Pro- vincial Park, Ontario to verify this. -

Vol. 76 Monday, No. 181 September 19, 2011 Pages 57897–58088

Vol. 76 Monday, No. 181 September 19, 2011 Pages 57897–58088 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Mar 15 2010 18:22 Sep 16, 2011 Jkt 223001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\19SEWS.LOC 19SEWS sroberts on DSK5SPTVN1PROD with RULES II Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 181 / Monday, September 19, 2011 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records PUBLIC Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Aaron Comeau Justin Rutledge Toronto ON

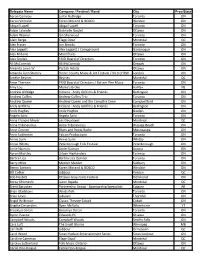

Delegate Name Company / Festival / Band City Prov/State Aaron Comeau Justin Rutledge Toronto ON Aaron Verhulst Karen Morand & BOSCO Windsor ON Abigail Lapell Abigail Lapell Toronto ON Adam Lalonde Gabrielle Goulet Ottawa ON Adam Warner Ian Sherwood Toronto ON Alain Berge Élage Diouf Montréal QC Alec Fraser Jon Brooks Toronto ON Alex Leggett Alex Leggett / Campground Gananoque ON Alex Millaire Moonfruits Ottawa ON Alex Sinclair FMO Board of Directors Toronto ON Ali McCormick Ali McCormick Ompah ON Amanda Lowe W. Partick Artists Ottawa ON Amanda Lynn Stubley Home County Music & Art Festival / 94.9 CHRW London ON Amélie Beyries Beyries Montréal QC Amie Therrien FMO Board of Directors / Balsam Pier Music Toronto ON Amy Lou Mama's Broke Halifax NS Andrew Aldridge Kidzent - Andy Griffiths & Friends Burlington ON Andrew Collins Andrew Collins Trio Toronto ON Andrew Queen Andrew Queen and the Campfire Crew Campbellford ON Andy Griffiths Kidzent - Andy Griffiths & Friends Burlington ON Andy Hughes Andy Hughes Guelph ON Angela Saini Angela Saini Toronto ON Anna Frances Meyer Les Deuxluxes Montreal QC Anna Tribinevicius Anna Tribinevicius Wasaga Beach ON Anne Connor Blues and Roots Radio Mississauga ON Anne Lederman Falcon Productions Toronto ON Annie Sumi Annie Sumi Whitby ON Annie Whitty Peterborough Folk Festival Peterborough ON Arnie Naiman Arnie Naiman Aurora ON Ayron Mortley Urban Highlanders Toronto ON Barbra Lica Barbra Lica Quintet Toronto ON Barry Miles Murder Murder Sudbury ON Benny Santoro Karen Morand & BOSCO Windsor ON Bill Collier -

Newsletter #47 January – February 2017 for Tangens Alumni and Friends

Newsletter #47 January – February 2017 For Tangens alumni and friends Coyote and dog attacks. I wrote about this in newsletters #31 and #32 in 2014. Since then I always walk dogs with stones in my back pack. I have not had to use the stones on coyotes since then, but I have used the stones a couple of times on approaching off-leash dogs, when yelling didn’t work (never hit one of course). No matter how “friendly” the owners claim the dogs are, they create a big problem if coming up to my pack, where all are on leash. Alex Carswell, owner of “Joey” (litter 08) recommended in #32 using a collapsible baton. I bought one, but I didn’t really manage it well enough. Recently, Joan Pleasant, owner of “Juju” (litter 09) wrote to recommend the Falcon Signal Horn Super Sound; lightweight, small, inexpensive, and can be attached to your belt or back pack. I will definitely buy one to try. An air horn like this can also be useful in other situations, including emergencies. I wonder though how the dogs you are trying to protect react to the super sound. I heard that it can be used to break up dog fights. Whippets in general don’t seem to be too sensitive to sounds, so hopefully they don’t get too scared if you use it for coyote attacks. On the topic of coyotes: I recently went to a presentation and book signing by the author of the book Coyote America. Coyotes are beautiful and interesting, even though they are also a nuisance. -

Population Genomic Analysis of North American Eastern Wolves (Canis Lycaon) Supports Their Conservation Priority Status

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Population Genomic Analysis of North American Eastern Wolves (Canis lycaon) Supports Their Conservation Priority Status Elizabeth Heppenheimer 1,† , Ryan J. Harrigan 2,†, Linda Y. Rutledge 1,3 , Klaus-Peter Koepfli 4,5, Alexandra L. DeCandia 1 , Kristin E. Brzeski 1,6, John F. Benson 7, Tyler Wheeldon 8,9, Brent R. Patterson 8,9, Roland Kays 10, Paul A. Hohenlohe 11 and Bridgett M. von Holdt 1,* 1 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA; [email protected] (E.H.); [email protected] (L.Y.R.); [email protected] (A.L.D); [email protected] (K.E.B.) 2 Center for Tropical Research, Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; [email protected] 3 Biology Department, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 1Z8, Canada 4 Center for Species Survival, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC 20008, USA; klauspeter.koepfl[email protected] 5 Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia 6 School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA 7 School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68583, USA; [email protected] 8 Environmental & Life Sciences, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 0G2, Canada; [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (B.R.P.) 9 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 0G2, Canada 10 North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27601, USA; [email protected] 11 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally. -

Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Southeastern Pre-Columbian Canids Kristin E

Journal of Heredity, 2016, 287–293 doi:10.1093/jhered/esw002 Original Article Advance Access publication January 16, 2016 Brief Communication Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Southeastern Pre-Columbian Canids Kristin E. Brzeski, Melissa B. DeBiasse, David R. Rabon Jr, Michael J. Chamberlain, and Sabrina S. Taylor Downloaded from From the School of Renewable Natural Resources, Louisiana State University Agricultural Center and Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 (Brzeski and Taylor); Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 (DeBiasse); Endangered Wolf Center, P.O. Box 760, Eureka, MO 63025 (Rabon); and Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 (Chamberlain). Address correspondence to Kristin E. Brzeski at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. http://jhered.oxfordjournals.org/ Received July 11, 2015; First decision August 17, 2015; Accepted January 4, 2016. Corresponding editor: Bridgett vonHoldt Abstract The taxonomic status of the red wolf (Canis rufus) is heavily debated, but could be clarified by examining historic specimens from the southeastern United States. We analyzed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from 3 ancient (350–1900 year olds) putative wolf samples excavated from middens at Louisiana State University on June 17, 2016 and sinkholes within the historic red wolf range. We detected 3 unique mtDNA haplotypes, which grouped with the coyote mtDNA clade, suggesting that the canids inhabiting southeastern North America prior to human colonization from Europe were either coyotes, which would vastly expand historic coyote distributions, an ancient coyote–wolf hybrid, or a North American evolved red wolf lineage related to coyotes. Should the red wolf prove to be a distinct species, our results support the idea of either an ancient hybrid origin for red wolves or a shared common ancestor between coyotes and red wolves. -

Chimpanzee Rights: the Philosophers' Brief

Chimpanzee Rights: The Philosophers’ Brief By Kristin Andrews Gary Comstock G.K.D. Crozier Sue Donaldson Andrew Fenton Tyler M. John L. Syd M Johnson Robert C. Jones Will Kymlicka Letitia Meynell Nathan Nobis David M. Peña-Guzmán Jeff Sebo 1 For Kiko and Tommy 2 Contents Acknowledgments…4 Preface Chapter 1 Introduction: Chimpanzees, Rights, and Conceptions of Personhood….5 Chapter 2 The Species Membership Conception………17 Chapter 3 The Social Contract Conception……….48 Chapter 4 The Community Membership Conception……….69 Chapter 5 The Capacities Conception……….85 Chapter 6 Conclusions……….115 Index 3 Acknowledgements The authors thank the many people who have helped us throughout the development of this book. James Rocha, Bernard Rollin, Adam Shriver, and Rebecca Walker were fellow travelers with us on the amicus brief, but were unable to follow us to the book. Research assistants Andrew Lopez and Caroline Vardigans provided invaluable support and assistance at crucial moments. We have also benefited from discussion with audiences at the Stanford Law School and Dalhousie Philosophy Department Colloquium, where the amicus brief was presented, and from the advice of wise colleagues, including Charlotte Blattner, Matthew Herder, Syl Ko, Tim Krahn, and Gordon McOuat. Lauren Choplin, Kevin Schneider, and Steven Wise patiently helped us navigate the legal landscape as we worked on the brief, related media articles, and the book, and they continue to fight for freedom for Kiko and Tommy, and many other nonhuman animals. 4 1 Introduction: Chimpanzees, Rights, and Conceptions of Personhood In December 2013, the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) filed a petition for a common law writ of habeas corpus in the New York State Supreme Court on behalf of Tommy, a chimpanzee living alone in a cage in a shed in rural New York (Barlow, 2017). -

Coywolf: Eastern Coyote Genetics, Ecology, Management, and Politics

Coywolf: Eastern Coyote Genetics, Ecology, Management, and Politics By Jonathan G. Way Published by Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research - www.EasternCoyoteResearch.com E-book • Citation: • Way, J.G. 2021. E-book. Coywolf: Eastern Coyote Genetics, Ecology, Management, and Politics. Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research, Barnstable, Massachusetts. 277 pages. Open Access URL: http://www.easterncoyoteresearch.com/CoywolfBook. • Copyright © 2021 by Jonathan G. Way, Ph.D., Founder of Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research. • Photography by Jonathan Way unless noted otherwise. • All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, e-mailing, or by any information storage, retrieval, or sharing system, without permission in writing or email to the publisher (Jonathan Way, Eastern Coyote Research). • To order a copy of my books, pictures, and to donate to my research please visit: • http://www.easterncoyoteresearch.com/store or MyYellowstoneExperience.org • Previous books by Jonathan Way: • Way, J. G. 2007 (2014, revised edition). Suburban Howls: Tracking the Eastern Coyote in Urban Massachusetts. Dog Ear Publishing, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. 340 pages. • Way, J. G. 2013. My Yellowstone Experience: A Photographic and Informative Journey to a Week in the Great Park. Eastern Coyote Research, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. 152 pages. URL: http://www.myyellowstoneexperience.org/bookproject/ • Way, J. G. 2020. E-book (Revised, 2021). Northeastern U.S. National Parks: What Is and What Could Be. Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research, Barnstable, Massachusetts. 312 pages. Open Access URL: http://www.easterncoyoteresearch.com/NortheasternUSNationalParks/ • Way, J.G. 2020. E-book (Revised, 2021). The Trip of a Lifetime: A Pictorial Diary of My Journey Out West. -

Eastern Coyote/Coywolf (Canis Latrans X Lycaon) Movement Patterns: Lessons Learned in Urbanized Ecosystems Jonathan G

Cities and the Environment (CATE) Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 2 7-20-2011 Eastern Coyote/Coywolf (Canis latrans x lycaon) Movement Patterns: Lessons Learned in Urbanized Ecosystems Jonathan G. Way Eastern Coyote Research, [email protected] Recommended Citation Way, Jonathan G. (2011) "Eastern Coyote/Coywolf (Canis latrans x lycaon) Movement Patterns: Lessons Learned in Urbanized Ecosystems," Cities and the Environment (CATE): Vol. 4: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cate/vol4/iss1/2 This Special Topic Article: Urban Wildlife is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cities and the Environment (CATE) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern Coyote/Coywolf (Canis latrans x lycaon) Movement Patterns: Lessons Learned in Urbanized Ecosystems Activity and movement patterns represent a fundamental aspect of a species natural history. Twenty four-hour movements of eastern coyotes or coywolves (Canis latrans x lycaon; hereafter eastern coyote for consistency purposes) ranged up to 31.9 linear km and averaged 23.5 + 7.3 (SD) km from 5-14 radio-fixes during each 24 hr monitoring period. Coyotes moved mostly at night and through altered open areas (e.g., powerlines, dumps) more than expected when compared to residential and natural areas. Coyotes inhabiting urbanized areas generally use residential areas for traveling and/or foraging. With large daily (or more aptly, nightly) movement patterns, resident coyotes can potentially be located anywhere within their large home ranges at any given time, as data revealed that one pack (3-4 individuals) can cover a combined 75-100 km per night, in a territory averaging 20-30 km2. -

COSSARO Candidate V, T, E Species Evaluation Form

Ontario Species at Risk Evaluation Report for Algonquin Wolf (Canis sp.), an evolutionarily significant and distinct hybrid with Canis lycaon, C. latrans, and C. lupus ancestry Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO) Assessed by COSSARO as THREATENED January 2016 Final Loup Algonquin (Canis sp.) Le loup Algonquin (Canis sp.) est un canidé de taille intermédiaire qui vit en meute familiale et qui se nourrit de proies comme le castor, le cerf de Virginie et l’orignal. Le loup Algonquin est le fruit d’une longue tradition d’hybridation et de rétrocroisement entre le loup de l’Est (Canis lycaon) (appelé aussi C. lupus lycaon), le loup gris (C. lupus) et le coyote (C. latrans). Bien qu’il fasse partie d’un complexe hybride répandu, le loup Algonquin peut se différencier des autres hybrides, comme le loup boréal des Grands Lacs, parce qu’il forme une grappe discrète, sur le plan génétique, composée d’individus étroitement apparentés à partir de laquelle il est possible de faire des estimations de filiation présumée. De plus, selon les données morphologiques, il est généralement plus grand que les canidés de type C. latrans et plus petit que les canidés de type C. lupus, bien qu’une identification fiable nécessite des données génotypiques. En Ontario, le loup Algonquin est principalement confiné dans le parc provincial Algonquin ainsi que dans les régions avoisinantes, dont certaines sont protégées. Ces régions englobent le parc provincial Killarney au sud de la région caractéristique des Hautes-Terres de Kawartha. Les relevés plus éloignés sont relativement rares et vraisemblablement attribuables à des incidents de dispersion occasionnels sur de grandes distances. -

Perspectives on the Conservation of Wild Hybrids ⇑ Astrid V

Biological Conservation 167 (2013) 390–395 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Perspective Perspectives on the conservation of wild hybrids ⇑ Astrid V. Stronen a, , Paul C. Paquet b,c a Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, ul. Waszkiewicza 1, 17-230 Białowieza,_ Poland b Raincoast Conservation Foundation, PO Box 86, Denny Island, British Columbia V0T 1B0, Canada c Department of Geography, University of Victoria, PO Box 3060, STN CSC, Victoria, British Columbia V8W 3R4, Canada article info abstract Article history: Hybridization processes are widespread throughout the taxonomic range and require conservation rec- Received 13 April 2013 ognition. Science can help us understand hybridization processes but not whether and when we ought Received in revised form 31 August 2013 to conserve hybrids. Important questions include the role of humans in hybridization and the value Accepted 1 September 2013 we place on natural and human-induced hybrids concerning their ecological function. Certain hybrids resulting from human actions have replaced the ecological role of extirpated or extinct parent taxa and this ecological role should be preserved. Conservation policies must increasingly recognize popula- Keywords: tions of wild organisms that hybridize naturally within the context of their historical ecological role. Nat- Canis ural selection acts on individual organisms and the range of characteristics displayed by individual Ecological niche Evolution hybrids constitute raw material for evolution. Guidelines must consider the conservation value of indi- Human values viduals and the ethical aspects of removing hybrids for the purpose of conserving population genetic Hybridization integrity. Conservation policies should focus on protecting the ecological role of taxa affected by hybrid- Policy ization.