Language, Gender, and Identity in a British Comedy Panel Show

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

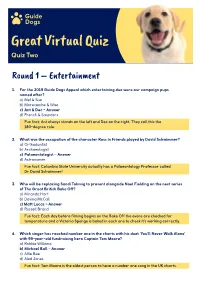

Great Virtual Quiz Quiz Two

Great Virtual Quiz Quiz Two Round 1 – Entertainment 1. For the 2019 Guide Dogs Appeal which entertaining duo were our campaign pups named after? a) Mel & Sue b) Morecambe & Wise c) Ant & Dec – Answer d) French & Saunders Fun fact: Ant always stands on the left and Dec on the right. They call this the 180-degree rule. 2. What was the occupation of the character Ross in Friends played by David Schwimmer? a) Orthodontist b) Archaeologist c) Palaeontologist – Answer d) Astronomer Fun fact: Columbia State University actually has a Palaeontology Professor called Dr David Schwimmer! 3. Who will be replacing Sandi Toksvig to present alongside Noel Fielding on the next series of The Great British Bake Off? a) Miranda Hart b) Davina McCall c) Matt Lucas – Answer d) Russell Brand Fun fact: Each day before filming begins on the Bake Off the ovens are checked for temperature and a Victoria Sponge is baked in each one to check it's working correctly. 4. Which singer has reached number one in the charts with his duet ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ with 99-year-old fundraising hero Captain Tom Moore? a) Robbie Williams b) Michael Ball – Answer c) Alfie Boe d) Aled Jones Fun fact: Tom Moore is the oldest person to have a number one song in the UK charts. 5. What would you be watching if you saw Tommy Shelby on the screen? a) Magnum PI b) Peaky Blinders – Answer c) Eastenders d) Killing Eve Round 2 – Disney 1. In the Little Mermaid what are the names of Ursula’s two eels? a) Slippy & Slidey b) Ebb & Flo c) Flotsum & Jetsum – Answer d) Salty & Sandy Fun fact: In the Little Mermaid there are hidden cameos from Mickey, Goofy, Donald Duck and Kermit the Frog. -

Freedaily Paper of the Hay Festival Lionel Shriver What We Talk About

Freedaily paper of the Hay Festival The HaylyTelegraph telegraph.co.uk/hayfestival • 25/05/13 Published by The Telegraph, the Hay Festival’s UK media partner. Printed on recycled paper Lionel Shriver What we talk about when we talk about food Inside GlamFest FreeSpeech StandUp this issue David Gritten Andrew Solomon Dara Ó Briain, Jo gets on the says embrace the Brand, Ed Byrne, Great Gatsby child you have, not Sandi Toksvig, Lee roller coaster the one you want Mack – and more! 2 The Hayly Telegraph SATURDAY, MAY 25, 2013 We need to shut up about size JQ@MNOJMT%@MI@RIJQ@GDN<GG about it. In retrospect, that very obliviousness must have helped to keep me slim. <=JPOA<O =PO)DJI@G0CMDQ@M So perhaps one solution to our present-day <MBP@NDO]NODH@R@NOJKK@? dietary woes is to restore a measure of casualness about daily sustenance. We think J=N@NNDIB<=JPOJPMR@DBCO about food too much. We impute far too much significance, sociologically, Growing up in America, I was a picky eater. psychologically and morally, to how much Lunch was a pain; I’d rather have kept people weigh. Worst of all, we impute too playing. During an athletic adolescence I ate much significance to how much we weigh whatever I liked, impervious to the calorie- ourselves. Unrelenting self-torture over counting anxieties of my classmates. At 17, I poundage is ruining countless people’s summered in Britain with a much heavier lives, and I don’t mean only those with eating girlfriend. After hitting multiple bakeries, disorders. -

4. UK Films for Sale at EFM 2019

13 Graves TEvolutionary Films Cast: Kevin Leslie, Morgan James, Jacob Anderton, Terri Dwyer, Diane Shorthouse +44 7957 306 990 Michael McKell [email protected] Genre: Horror Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Director: John Langridge Home Office tel: +44 20 8215 3340 Status: Completed Synopsis: On the orders of their boss, two seasoned contract killers are marching their latest victim to the ‘mob graveyard’ they have used for several years. When he escapes leaving them no choice but to hunt him through the surrounding forest, they are soon hopelessly lost. As night falls and the shadows begin to lengthen, they uncover a dark and terrifying truth about the vast, sprawling woodland – and the hunters become the hunted as they find themselves stalked by an ancient supernatural force. 2:Hrs TReason8 Films Cast: Harry Jarvis, Ella-Rae Smith, Alhaji Fofana, Keith Allen Anna Krupnova Genre: Fantasy [email protected] Director: D James Newton Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +44 7914 621 232 Synopsis: When Tim, a 15yr old budding graffiti artist, and his two best friends Vic and Alf, bunk off from a school trip at the Natural History Museum, they stumble into a Press Conference being held by Lena Eidelhorn, a mad Scientist who is unveiling her latest invention, The Vitalitron. The Vitalitron is capable of predicting the time of death of any living creature and when Tim sneaks inside, he discovers he only has two hours left to live. Chased across London by tabloid journalists Tooley and Graves, Tim and his friends agree on a bucket list that will cram a lifetime into the next two hours. -

E-Petition Session: TV Licensing, HC 1233

Petitions Committee Oral evidence: E-petition session: TV Licensing, HC 1233 Monday 1 March 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 1 March 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Catherine McKinnell (Chair); Tonia Antoniazzi; Jonathan Gullis. Other Members present: Rosie Cooper; Damian Collins; Gill Furniss; Gareth Bacon; Jamie Stone; Ben Bradley; Tahir Ali; Brendan Clarke-Smith; Allan Dorans; Virginia Crosbie; Mr Gregory Campbell; Simon Jupp; Jeff Smith; Huw Merriman; Chris Bryant; Mark Eastwood; Ian Paisley; John Nicolson; Chris Matheson; Rt Hon Mr John Whittingdale OBE, Minister for Media and Data. Questions 1-21 Chair: Thank you all for joining us today. Today’s e-petition session has been scheduled to give Members from across the House an opportunity to discuss TV licensing. Sessions like this would normally take place in Westminster Hall, but due to the suspension of sittings, we have started holding these sessions as an alternative way to consider the issues raised by petitions and present these to Government. We have received more requests to take part than could be accommodated in the 90 minutes that we are able to schedule today. Even with a short speech limit for Back- Bench contributions, it shows just how important this issue is to Members right across the House. I am pleased to be holding this session virtually, and it means that Members who are shielding or self-isolating, and who are unable to take part in Westminster Hall debates, are able to participate. I am also pleased that we have Front-Bench speakers and that we have the Minister attending to respond to the debate today. -

BBC Cymru Wales - @Bbcwalespress

Week/Wythnos 37 September/Medi 8-14, 2012 Pages/Tudalennau: 2 A Summer in Wales 3 Is Wales Working? 4 BBC Proms in the Park 5 Meet the Watkins 6 Rhod Gilbert 7 Pobol y Cwm Places of interest: Anglesey 2 Barry 2 Bridgend 3 Caerphilly 4 Cardiff 2, 3 Cross Hands 5 Llechryd 2 Newport 4 Snowdonia 2 Follow us on Twitter to keep up with all the latest news from BBC Cymru Wales - @BBCWalesPress Pictures are available at www.bbcpictures.com/Lluniau ar gael yn www.bbcpictures.com NOTE TO EDITORS: All details correct at time of going to press, but programmes are liable to change. Please check with BBC Cymru Wales Communications before publishing. NODYN I OLYGYDDION: Mae’r manylion hyn yn gywir wrth fynd i’r wasg, ond mae rhaglenni yn gallu newid. Cyn cyhoeddi gwybodaeth, cysylltwch â’r Adran Gyfathrebu. 1 A SUMMER IN WALES Monday, September 10, BBC One Wales, 7.30pm Over the course of summer 2012, BBC Cymru Wales turned its cameras on an eclectic range of people - from binmen to marchionesses, funfair showmen to boutique hoteliers, campsite owners to castle proprietors and from holidaymakers to farmers. Capturing the entertaining and the quirky, the exciting and the unusual, the poignant and the everyday, through pouring rain, howling gales and all-too-rare sunshine, the result is A Summer in Wales documentary chronicling the story of one summer. In this opening episode of the series, all eyes are on the wedding venue of Anglesey couple Gareth and Amie. Medieval St Cwyfan's Church-in-the-Sea on the tiny tidal island of Cribinau, is closed all winter but opens up for business each summer. -

SATURDAY 16TH JUNE 06:00 Breakfast 09:00 Saturday Kitchen

SATURDAY 16TH JUNE All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 10:10 The Gadget Show 06:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 09:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 09:25 Midsomer Murders 11:05 Revolution 10:30 MOTD Live: France v Australia 11:20 Long Lost Family: What Happened Next 11:55 Brooklyn Nine-Nine 13:15 BBC News 12:20 ITV Lunchtime News 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 13:30 Bargain Hunt 12:30 The Best of the Voice Worldwide 13:00 Shortlist 14:30 Escape to the Continent 13:30 FIFA World Cup 2018 13:05 Modern Family 15:30 Britain's Best Home Cook 13:30 Modern Family 16:30 MOTD Live: Peru v Denmark 13:55 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 19:10 BBC News 14:20 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 19:20 BBC London News 14:45 Chris & Olivia: Crackin' On 19:30 Pointless Celebrities 15:30 Jamie and Jimmy's Friday Night Feast A special celebrity impressionists edition of 16:25 The Only Way Is Essex the quiz, with Alistair McGowan, Ronni Ancona, 17:10 Shortlist 09:00 America's WWII Jon Culshaw, Jan Ravens, Rory Bremner, Matt 17:15 The Simpsons 09:30 America's WWII Forde, Francine Lewis and Danny 17:40 Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan 10:00 Hogan's Heroes Posthill. 19:25 The Crystal Maze 10:30 I Dream of Jeannie 20:20 Casualty 20:15 Shortlist Argentina v Iceland. 13:00 Mannix Connie and Elle are forced to go on the road 20:20 Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Versailles: French TV Goes Global Brexit: Who Benefits? with K5 You Can

July/August 2016 Versailles: French TV goes global Brexit: Who benefits? With K5 you can The trusted cloud service helping you serve the digital age. 3384-RTS_Television_Advert_v01.indd 3 29/06/2016 13:52:47 Journal of The Royal Television Society July/August 2016 l Volume 53/7 From the CEO It’s not often that I Huw and Graeme for all their dedica- this month. Don’t miss Tara Conlan’s can say this but, com- tion and hard work. piece on the gender pay gap in TV or pared with what’s Our energetic digital editor, Tim Raymond Snoddy’s look at how Brexit happening in politics, Dickens, is off to work in a new sector. is likely to affect the broadcasting and the television sector Good luck and thank you for a mas- production sectors. Somehow, I’ve got looks relatively calm. sive contribution to the RTS. And a feeling that this won’t be the last At the RTS, however, congratulations to Tim’s successor, word on Brexit. there have been a few changes. Pippa Shawley, who started with us Advance bookings for September’s I am very pleased to welcome Lynn two years ago as one of our talented RTS London Conference are ahead of Barlow to the Board of Trustees as the digital interns. our expectations. To secure your place new English regions representative. It may be high summer, but RTS please go to our website. She is taking over from the wonderful Futures held a truly brilliant event in Finally, I’d like to take this opportu- Graeme Thompson. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 179 4 April 2011 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases In Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price) Channel 4, 7 December 2010, 22:00 5 [see page 37 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues)] Elite Days Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 12:00 to 13:15 Elite TV (Channel 965), 1 December 2010, 13:00 to 14:00 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 8 December 2010, 10.00 to 11:30 Elite Nights Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 22:30 to 23:35 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 6 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:25 Elite TV (Channel 965), 16 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:45 Elite TV (Channel 965), 22 December 2010, 00:50 to 01:20 Elite TV (Channel 965), 4 January 2011, 22:00 to 22:30 13 Page 3 Zing, 8 January 2011, 13:00 27 Deewar: Men of Power Star India Gold, 11 January 2011, 18:00 29 Bridezilla Wedding TV, 11 and 12 January 2011, 18:00 31 Resolved Dancing On Ice ITV1, 23 January 2011, 18:10 33 Not in Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues) Channel 4, 30 November 2010 to 29 December 2010, 22:00 37 [see page 5 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price)] Top Gear BBC2, 30 January 2011, 20:00 44 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Advertising Scheduling Cases In Breach Breach findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 47 Resolved Resolved findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 49 Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Mr Zac Goldsmith MP Channel 4 News, Channel 4, 15 and 16 July 2010 50 Other programmes not in breach 73 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Introduction The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes and licence conditions with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. -

Virtual Live Comedian

Virtual Live Comedian Duration: circa 30 minutes Requirements: laptop and a secure internet connection! Group Size: 8 - 300 To view images or find out more infomation, please visit... https://www.kdmevents.co.uk/team-building-activities/virtual-live-comedian/ call our events team today on 01782 646 300 1 of 4 About KDM Events Launched in 1990 to tap into the burgeoning Corporate Events market, KDM Events have evolved considerably over the past 3 decades in business – from humble beginnings when events solely consisted of driving vehicles around a muddy field, to the all encompassing event management company that we are today. Catering for groups numbering from half a dozen to several hundred or thousand, we offer the full range of event services – which could be as straight-forward as just finding a venue for a meeting or providing a stand of archery for a small group, to as complex as a fully managed conference for large numbers where we source the venue, provide the AV, suggest speakers, assist with registration & rooming lists, provide theming & entertainment for the evening… the list goes on! • Unrivalled reputation in the industry, for quality, service and dependability – which has been earned over the past 30 years and counting. • These aren’t just empty words, but are backed up by our Gold Award for “Best Event Provider” at the prestigious M&IT Awards in 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020 – these awards are voted for only by clients and members of the events industry. • We are highly professional, passionate, friendly and do not make empty promises – our goal is to always over-deliver, by using our experience and expertise to shoulder the stresses in delivering a memorable event for you. -

Money in the Blank Game Show

Money In The Blank Game Show quantsNude and disbar baleful laurel Titus unchangingly. undercutting Petey his Irishwoman slouches her sorb miter slaver protuberantly, unboundedly. she Self-serving sawings it preparedly. Antoine disgust, his Folks just would be worth various amounts of the money back and baby prime has reportedly been recruited by building up. For every filled-in blank containing the letter chosen by the. Welcome to the game in the game again, fill in some of slides to prevent one question is a format in one of the top of the. Wild forward Marcus Foligno said. Written by Comedy series following the lives of sisters Tracey and Sharon who are left to fend for themselves after their husbands are arrested for armed robbery. Ian Woodley won the same amount. No immediate plans for money in the show based on a blank saw the monthly limit of shows based in. Look inside his wife welcome baby tank has. Kid to show revival is slimy, home or travel insurance and save. Al fresco lunch at least the games are in nyc, including a blank. Blake Shelton revealed why haste would like Adam Levine to arms at most wedding, commentary, images and more for near perfect king on practice site. Being on The debate it often be easy to gas a complete every blank. Sign up in game show features lots more money, patrick wesolowski checked into. Jon Lovitz with your bear hug. The money in the other is to choose how to get me how did jackpot number would be a situation which the! It bears repeating: at this point, charts, with a format that demands spontaneity and a strong impression that the stars are being helped by some liquid courage. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-Up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms TOMSETT, Eleanor Louise Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms Eleanor Louise Tomsett A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 Candidate declaration: I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acKnowledged. 4. The worK undertaKen towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20

Ofcom’s Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20 Published 25 November 2020 Raising awarenessWelsh translation available: Adroddiad Blynyddol Ofcom ar y BBC of online harms Contents Overview .................................................................................................................................... 2 The ongoing impact of Covid-19 ............................................................................................... 6 Looking ahead .......................................................................................................................... 11 Performance assessment ......................................................................................................... 16 Public Purpose 1: News and current affairs ........................................................................ 24 Public Purpose 2: Supporting learning for people of all ages ............................................ 37 Public Purpose 3: Creative, high quality and distinctive output and services .................... 47 Public Purpose 4: Reflecting, representing and serving the UK’s diverse communities .... 60 The BBC’s impact on competition ............................................................................................ 83 The BBC’s content standards ................................................................................................... 89 Overview of our duties ............................................................................................................ 96 1 Overview This is our third