Thesis Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Crying Now?

Originally Published: Nov. 14, 2009 $2.00 PERIODICAL NEWSPAPER CLASSIFICATION C DATED MATERIAL PLEASE RUSH!! M Vol. 29, No. 10 “For The Buckeye Fan Who Needs To Know More” November 14, 2009 Y Who’s Crying Now? K Pryor Leads Buckeyes To Win In His First Trip Back To Pa. for the Nittany Lions, Pryor was inconsolable By ADAM JARDY on the sidelines with his head in his hands. Buckeye Sports Bulletin Staff Writer It was a fact he said the OSU strength and conditioning coaches constantly pointed out In the end, one unhappy Penn State fan to him during summer workouts in an effort got in the final word. to make him work harder. The game was over, and the battle had If he needed any further reminder, it been won. Ohio State had gone into Beaver arrived the week before the Nov. 7 rematch Stadium and closed out a 24-7 victory under with the Nittany Lions in the form of a T- the cover of darkness. In the process, sopho- shirt courtesy of a student marketing group more quarterback and western Pennsylvania at Penn State. Four days before the game, native Terrelle Pryor had exacted his revenge a photo of a shirt depicting Pryor and the on the fan base of a program that had reviled Nittany Lion mascot arm-in-arm with the him immediately upon his decision to sign lion holding a box of tissues above the head- with the Buckeyes. ing “The Nutcracker: A Terrelle Cryer Story” After making what amounted to a victory started making the rounds on the Internet. -

Events and Information F O R T H E Tc U Community

EVENTS AND INFORMATION F O R T H E TC U COMMUNITY VO L. 1 2 N 0. 3 8 J U L Y 3 0, 2 0 0 7 Brite president D. Newell Here are the nation's top-1 O coaches according to SI.corn's Stewart Mandel. EVENTS Williams chosen moderator of 1. Pete Carroll, USC 2. Urban Meyer, Florida Today-Aug. 3 Christian Church nationwide Frog Camp, Alpine B.* DR. D. NEWELL WILLIAMS WAS INSTALLED 3. Jim Tressel, Ohio State as moderator of the Christian Church (Disciples 4. Mack Brown, Texas JulY. 31-Aug. 2 Neil Dougherty's Basketball Day Camp II, 8:30 5. Bob Stoops, Oklahoma of Christ) for 2007-2009 during the group's a.m.-noon: entering Grades 1-4; 1-4:30 p.m.: national General Assembly meeting in Fort Worth 6. Frank Beamer, Virginia Tech entering Grades 5-8, Schollmaier Basketball Complex. Call ext. 7968 for more information. last week. Newell has been president of Brite 7. Jim Grobe, Wake Forest Divinity School atTCU since 2003. He also serves 8. Rich Rodriguez, West Virginia Aug. 1 as professor of modern and American church 9. Mark Richt, Georgia Crucial Conversations Reunion Breakfast, 8- 9:30 a.m., HR Conference Room.** history at Brite. 10. Gary Patterson, TCU + An author and editor, Newell previously taught Aug.2 Focus on Wellness Luncheon, Powerful Super at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis Department of social work Foods presented by Allison Reyna, 11 :30 a.m.- where he also served as vice president and dean 1 p.m., Bass Living Room.** during the 1990s. -

Coaches P31-50.Indd

1 TEAM COACHING STAFF • 31 HEAD COACH RALPH FRIEDGEN MARYLAND ‘70 • SIXTH YEAR AT MARYLAND Ralph Friedgen, the (30-3) in the Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl and over West Virginia Friedgen brought 32 years of assistant coaching experience second-winningest fifth- (41-7) in the Toyota Gator Bowl. (including 21 as an offensive coordinator either in college or year head coach in Atlantic His offensive success notwithstanding, Friedgen’s the NFL) with him in his return to College Park. Coast Conference history, teams at Maryland have been superb on defense, ranking The 59-year-old Friedgen (pronounced FREE-jun) enters his sixth year at the among the nation’s leaders annually while producing the owns the rare distinction of coordinating the offense for University of Maryland with ACC’s Defensive Player of the Year in three of the last both a collegiate national champion (Georgia Tech in 1990) a reputation as one of the five seasons (E.J. Henderson in 2001 and 2002; D’Qwell and a Super Bowl team (San Diego in 1994). top minds in college football. This season, Friedgen will Jackson in 2005). Friedgen spent 20 seasons with the aforementioned also assume the duties of the team’s offensive coordinator, Named the winner of the Frank Broyles Award as the Ross in coaching stops at The Citadel, Maryland, Georgia marking the first time he will call the offensive plays in his top assistant coach in the country in 1999 while at Tech, Tech and the NFL’s San Diego Chargers. He returned to tenure at Maryland. -

Head Coach Suspended, Fined By

Originally Published: March 19, 2011 $2.50 PERIODICAL NEWSPAPER CLASSIFICATION DATED MATERIAL PLEASE RUSH!! C M Vol. 30, No. 18 “For The Buckeye Fan Who Needs To Know More” March 19, 2011 Y Matta’s Road K To OSU Began Tressel In Hometown By ADAM JARDY Buckeye Sports Bulletin Staff Writer The town of Hoopeston, Ill., is not the kind of place one stumbles upon by accident. A dot on the map nestled just inside the state’s eastern border, it is first mentioned as you drive from the east by a sign 16 miles out on Indiana State Route 26. As you cross the Indiana-Illinois state line headed westbound, the road surface changes as the destination Takes Hit approaches. Finally, a two-paneled green road sign greets visitors Head Coach Suspended, Fined who reach the city limit. The top panel notes the name of the town and the population, but it is the bottom half that proclaims the name of Hoopeston’s most famous native son. By OSU; Will Keep His Job In three lines, the sign reads, “Home of Big 10 Coach Thad Matta.” By JEFF SVOBODA In the mid-1980s, Hoopeston was more than just a loca- Buckeye Sports Bulletin Staff Writer tion on a map. It was a thriving, passionate city that found itself rallying around a common cause – high school bas- Despite coming to the conclusion that head football coach ketball. During a period from 1984-86, the boys basketball Jim Tressel violated his contract, athletic department proto- team put together a string of seasons still vividly recalled by col and NCAA bylaw 10.1 by failing to report information that the town’s remaining citizens. -

NCAA Division I Football Records (Coaching Records)

Coaching Records All-Divisions Coaching Records ............. 2 Football Bowl Subdivision Coaching Records .................................... 5 Football Championship Subdivision Coaching Records .......... 15 Coaching Honors ......................................... 21 2 ALL-DIVISIONS COachING RECOrds All-Divisions Coaching Records Coach (Alma Mater) Winningest Coaches All-Time (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct.† 35. Pete Schmidt (Alma 1970) ......................................... 14 104 27 4 .785 (Albion 1983-96) BY PERCENTAGE 36. Jim Sochor (San Fran. St. 1960)................................ 19 156 41 5 .785 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four-year colleges (regardless (UC Davis 1970-88) of division or association). Bowl and playoff games included. 37. *Chris Creighton (Kenyon 1991) ............................. 13 109 30 0 .784 Coach (Alma Mater) (Ottawa 1997-00, Wabash 2001-07, Drake 08-09) (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct.† 38. *John Gagliardi (Colorado Col. 1949).................... 61 471 126 11 .784 1. *Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) ........................ 24 289 22 3 .925 (Carroll [MT] 1949-52, (Mount Union 1986-09) St. John’s [MN] 1953-09) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) ......................... 13 105 12 5 .881 39. Bill Edwards (Wittenberg 1931) ............................... 25 176 46 8 .783 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Case Tech 1934-40, Vanderbilt 1949-52, 3. Frank Leahy (Notre Dame 1931) ............................. 13 107 13 9 .864 Wittenberg 1955-68) (Boston College 1939-40, 40. Gil Dobie (Minnesota 1902) ...................................... 33 180 45 15 .781 Notre Dame 41-43, 46-53) (North Dakota St. 1906-07, Washington 4. Bob Reade (Cornell College 1954) ......................... 16 146 23 1 .862 1908-16, Navy 1917-19, Cornell 1920-35, (Augustana [IL] 1979-94) Boston College 1936-38) 5. -

|||GET||| Scandals in College Sports 1St Edition

SCANDALS IN COLLEGE SPORTS 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Shaun R Harper | 9781317569428 | | | | | The 10 Biggest Scandals in College Football History I knew. Yeah I know!! What will be the post scheme? We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our site, show personalized content and targeted ads, analyze site traffic, and understand where our audiences come from. In fact, recruited athletes at Harvard are almost twice as likely to be white, and Scandals in College Sports 1st edition as likely to be Asian, as all non-ALDC admits. Irvine's Top 3 Convenience Stores Looking to explore the top convenience stores in town? An undisclosed player was accused of having another person take his SAT in Detroit so he could become eligible as a freshman, after failing the ACT three times. They plead guilty almost a year after they were first Scandals in College Sports 1st edition. From brawls to rule violations, from bribery to sexscapades, some scandals are so huge that they will be remembered by the sports world forever. Instead, they were promised relaxed supervision under coach Gary Barnett. A history that included national titles in and10 Conference titles, and 11 Bowl appearances. Rich parents coach their children to become fluent in a secret language of code words— scullingcradlingstate squash tournamen t—whose utterances may, years later, open the very gates of privilege through which the parents themselves once passed. There were reports of drug and alcohol use while Barnett was in charge and allegedly strippers were hired for recruiting parties. For now, the impact is that Baylor's name is beyond tarnished and the team is struggling to win games and sign recruits following two coaching changes in two years. -

Eight National Championships

EIGHT NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS Rank SEPT 26 Fort Knox W 59-0 OCT 03 Indiana W 32-21 10 Southern California W 28-12 1 17 Purdue W 26-0 1 24 at Northwestern W 20-6 1 31 at #6 Wisconsin L 7-17 6 NOV 07 Pittsburgh W 59-19 10 14 vs. #13 Illinois W 44-20 5 21 #4 Michigan W 21-7 3 28 Iowa Seahawks W 41-12 1942 NATIONAL CHAMPIONS – ASSOCIATED PRESS Front Row: William Durtschi, Robert Frye, Les Horvath, Thomas James, Lindell Houston, Wilbur Schneider, Richard Palmer, William Hackett, George Lynn, Martin Amling, Warren McDonald, Cyril Lipaj, Loren Staker, Charles Csuri, Paul Sarringhaus, Carmen Naples, Ernie Biggs. Second Row: William Dye, Frederick Mackey, Caroll Widdoes, Hal Dean, Thomas Antenucci, George Slusser, Thomas Cleary, Paul Selby, William Vickroy, Jack Roe, Robert Jabbusch, Gordon Appleby, Paul Priday, Paul Matus, Robert McCormick, Phillip Drake, Ernie Godfrey. Third Row: Paul Brown (Head Coach), Hugh McGranahan, Paul Bixler, Cecil Souders, Kenneth Coleman, James Rees, Tim Taylor, William Willis, William Sedor, John White, Kenneth Eichwald, Robert Shaw, Donald McCafferty, John Dugger, Donald Steinberg, Dante Lavelli, Eugene Fekete. Though World War II loomed over the nation, Ohio State football fans reveled in one of the most glorious seasons ever. The Buckeyes captured the school’s first national championship as well as a Big Ten title, finishing the year 9-1 and ranked No. 1 in the Associated Press poll. Led by a star-studded backfield that included Les Horvath, Paul Sarringhaus and Gene Fekete, OSU rolled to 337 points, a record that stood until 1969. -

82Nd Annual Convention of the AFCA

82nd annual convention of the AFCA. JANUARY 9-12, 2005 * LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY President's Message It was an ordinary Friday night high school football game in Helena, Arkansas, in 1959. After eating our pre-game staples of roast beef, green beans and dry toast, we journeyed to the stadium for pre- game. As rain began to fall, a coach instructed us to get in a ditch to get wet so we would forget about the elements. By kickoff, the wind had increased to 20 miles per hour while the temperature dropped over 30 degrees. Sheets of ice were forming on our faces. Our head coach took the team to the locker room and gave us instructions for the game as we stood in the hot showers until it was time to go on the field. Trailing 6-0 at halftime, the officials tried to get both teams to cancel the game. Our coach said, "Men, they want us to cancel. If we do, the score will stand 6-0 in favor of Jonesboro." There was a silence broken by his words, "I know you don't want to get beat 6-0." Well, we finished the game and the final score was 13-0 in favor of Jonesboro. Forty-five years later, it is still the coldest game I have ever been in. [ILLUSTRATION OMITTED] No one likes to lose, but for every victory, there is a loss. As coaches, we must use every situation to teach about life and how champions handle both the good and the bad. I am blessed to work with coaches who care about each and every player. -

The Ohio State University V. Cafepress

Case: 2:16-cv-01052-EAS-TPK Doc #: 1 Filed: 11/03/16 Page: 1 of 32 PAGEID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY : Plaintiff, : : Case No.: : Judge: CAFEPRESS, INC. : Defendant. : COMPLAINT FOR TRADEMARK INFRINGEMENT, UNFAIR COMPETITION, PASSING OFF, COUNTERFEITING, AND VIOLATION OF RIGHT OF PUBLICITY Plaintiff The Ohio State University ("Ohio State”) for its Complaint against D efendant CafePress, Inc. (“CafePress”) (“Defendant”), states as follows: Nature of the Case 1. This is an action for trademark infringement, unfair competition, passing off and counterfeiting under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1114 and § 1125(a), relating to the unlawful appropriation of Ohio State’s registered and common law trademarks, and violation of the rights of publicity assigned to Ohio State by head football coach Urban F. Meyer (“Meyer”) under O.R.C. § 2741, et seq., by Defendant in its design, manufacture, promotion, advertising, sale and shipping of counterfeit and infringing T-shirts and other merchandise online. 2. Plaintiff Ohio State is a public institution of higher education, with its main campus located in Columbus, Ohio, and regional campuses across the state. The University is dedicated to undergraduate and graduate teaching and learning; research and innovation; and 1 Case: 2:16-cv-01052-EAS-TPK Doc #: 1 Filed: 11/03/16 Page: 2 of 32 PAGEID #: 2 statewide, national, and international outreach and engagement. Both undergraduate and graduate students also connect with the University and broader community through an array of leadership, service, athletic, artistic, musical, dramatic, and other organizations and events. -

TCU Football Release

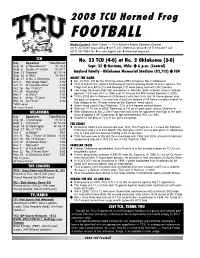

2008 TCU Horned Frog FOOTBALL Media Contact: Mark Cohen — TCU Athletics Media Relations Director (817) 257-5394 direct office (817) 257-7969 main office (817) 343-2017 cell (817) 257-7964 fax [email protected] www.GoFrogs.com TCU Day Opponent Time/Result No. 23 TCU (4-0) at No. 2 Oklahoma (3-0) Aug. 30 at New Mexico* W, 26-3 Sept. 27 Norman, Okla. 6 p.m. (Central) Sept. 6 Stephen F. Austin W, 67-7 Sept. 13 Stanford W, 31-14 Gaylord Family - Oklahoma Memorial Stadium (82,112) FSN Sept. 20 at SMU W, 48-7 Sept. 27 at No. 2 Oklahoma 6:00 ABOUT THE GAME Oct. 4 San Diego State* 5:00 No. 23 TCU, 4-0 for the first time since 2003, travels to No. 2 Oklahoma. Oct. 11 at Colorado State* 2:30 TCU is tied for the nation’s third-longest current winning streak at seven games. The Oct. 16 No. 11 BYU* 7:00 Frogs trail only BYU (14) and Georgia (11) while being tied with USC (seven). Oct. 25 Wyoming* 5:00 The Frogs have won their last two games in Norman. Both victories came in season Nov. 1 at UNLV* 7:00 openers. TCU won 20-7 in 1996 and 17-10 over the fifth-ranked Sooners in 2005. Nov. 6 at No. 17 Utah* 7:00 TCU’s 2005 win in Norman is Oklahoma’s only loss in its last 34 home games over the past six seasons. It is also one of just two defeats in 58 home contests overall for Nov. -

Jim Tressel Profile

Jim Tressel James P. Tressel became the ninth president of Youngstown State University in July 2014 and has been busy moving the campus forward on many fronts ever since. Under Tressel’s leadership, enrollment increased for the first time in five years and the university attracted it’s most academically-accomplished freshman class ever. In addition, the university revamped its development operations and hit record fund-raising levels, announced its first Rhodes Scholar recipient, reconfigured its executive leadership organization, froze tuition for two consecutive years and expanded its scholarship offerings. The university is also partnering with two private developers to construct new apartment style student housing on campus and is working with the city to improve major gateways to YSU. Prior to becoming YSU president, Tressel was executive vice president for Student Success at the University of Akron, where he was charged with restructuring and leading the efforts of a newly created division dedicated to the academic and career success of students. A native of Northeast Ohio, Tressel graduated from Berea High School in suburban Cleveland in 1971. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Education from Baldwin-Wallace College in 1975 and a master’s degree in Education from the University of Akron in 1977. He also holds honorary degrees from YSU in 2001 and Baldwin-Wallace in 2003. He first came to YSU in 1986 as head football coach. Within two seasons, the Penguins were in the NCAA Playoffs. He was named executive director of Intercollegiate Athletics in 1994. In his 15-year tenure as head football coach, Tressel’s teams amassed a record of 135-52-2, appeared in the playoffs 10 times and won four national championships. -

Page 1 of 2 Ohio State Football Traditions: Pay Forward 12/21/2008

Ohio State Football Traditions: Pay Forward Page 1 of 2 Username: Password: Click here to register for your sideline pass HOME TRESSEL TRADITION PEOPLE EXCELLENCE FACILITIES SCHEDULE NEWS BUCKEYE LEAVES GALLERY VIDEOS INTERACTIVE BUCKEYE TROOPS In 1944, we were Big Ten champions and we thought we were national champions, but Army, because of the war, was voted number one. I think we were the civilian champs. Warren Amling 1944-46: OSU and National Football Foundation Hall of Fame YSU OU USC TROY UM UW PU MSU PSU NU UI UM 08/30 09/06 09/13 09/20 09/27 10/04 10/11 10/18 10/25 11/08 11/15 11/22 Block O Tradition Brutus Buckeye Pay Forward Buckeye Grove Buckeye Leaves Captain's Breakfast You Can Always Pay Forward Cheerleaders By Bob Greene, Tribune Columnist Copyright Chicago Tribune (c) 1995 Carmen Ohio COLUMBUS, Ohio - Woody Hayes used to have a saying. He would drop it into Gold Pants conversations all the time. “You can never pay back,” he would say. “So you Ohio Stadium should always try to pay forward.” I never understood precisely what he meant. The words sounded good, but I wasn’t certain of their meaning. But in the years Pay Forward since Hayes’ death I have come to learn that the “paying forward” line was not some empty slogan for him. It was the credo by which he lived his life and now the Retired Jerseys dividends of his having paid forward are becoming ever more evident. Skull Session It happened again the other day.