College Athletics—Chasing the Big Bucks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Arkansas Razorbacks 2005 Football

ARKANSAS RAZORBACKS 2005 FOOTBALL HOGS TAKE ON TIGERS IN ANNUAL BATTLE OF THE BOOT: Arkansas will travel to Baton Rouge to take on the No. 3 LSU Tigers in the annual Battle of the Boot. The GAME 11 Razorbacks and Tigers will play for the trophy for the 10th time when the two teams meet at Tiger Stadium. The game is slated for a 1:40 p.m. CT kickoff and will be tele- Arkansas vs. vised by CBS Sports. Arkansas (4-6, 2-5 SEC) will be looking to parlay the momentum of back-to-back vic- tories over Ole Miss and Mississippi State into a season-ending win against the Tigers. Louisiana State LSU (9-1, 6-1 SEC) will be looking clinch a share of the SEC Western Division title Friday, Nov. 25, Baton Rouge, La. and punch its ticket to next weekend’s SEC Championship Game in Atlanta, Ga. 1:40 p.m. CT Tiger Stadium NOTING THE RAZORBACKS: * Arkansas and LSU will meet for the 51st time on the gridiron on Friday when the two teams meet in Baton Rouge. LSU leads the series 31-17-2 including wins in three of the Rankings: Arkansas (4-6, 2-5 SEC) - NR last four meetings. The Tigers have won eight of 13 meetings since the Razorbacks Louisiana State (9-1, 6-1 SEC) - (No. 3 AP/ entered the SEC in 1992. (For more on the series see p. 2) No. 3 USA Today) * For the 10th-consecutive year since its inception, Arkansas and LSU will be playing for The Coaches: "The Golden Boot," a trophy shaped like the two states combined. -

Who's Crying Now?

Originally Published: Nov. 14, 2009 $2.00 PERIODICAL NEWSPAPER CLASSIFICATION C DATED MATERIAL PLEASE RUSH!! M Vol. 29, No. 10 “For The Buckeye Fan Who Needs To Know More” November 14, 2009 Y Who’s Crying Now? K Pryor Leads Buckeyes To Win In His First Trip Back To Pa. for the Nittany Lions, Pryor was inconsolable By ADAM JARDY on the sidelines with his head in his hands. Buckeye Sports Bulletin Staff Writer It was a fact he said the OSU strength and conditioning coaches constantly pointed out In the end, one unhappy Penn State fan to him during summer workouts in an effort got in the final word. to make him work harder. The game was over, and the battle had If he needed any further reminder, it been won. Ohio State had gone into Beaver arrived the week before the Nov. 7 rematch Stadium and closed out a 24-7 victory under with the Nittany Lions in the form of a T- the cover of darkness. In the process, sopho- shirt courtesy of a student marketing group more quarterback and western Pennsylvania at Penn State. Four days before the game, native Terrelle Pryor had exacted his revenge a photo of a shirt depicting Pryor and the on the fan base of a program that had reviled Nittany Lion mascot arm-in-arm with the him immediately upon his decision to sign lion holding a box of tissues above the head- with the Buckeyes. ing “The Nutcracker: A Terrelle Cryer Story” After making what amounted to a victory started making the rounds on the Internet. -

Download Brochure (PDF)

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2019 PRESENTED BY BENEFITTING THE THE LEGACY OF JOHN FRANKLIN BROYLES Frank Broyles always said he lived a “charmed life,” and it was true. He leaves behind a multitude of legacies certain never to be replicated. Whether it was his unparalleled career in college athletics as an athlete, coach, athletic administrator and broadcaster, or his Broyles, SEC 1944 Player of the Year, handled all the passing (left) and punting (right) from his tailback spot playing for Georgia Tech under legendary Coach tireless work in the fourth quarter of his life Bobby Dodd as an Alzheimer’s advocate, his passion was always the catalyst for changing the world around him for the better, delivered with a smooth Southern drawl. He felt he was blessed to work for more than 55 years in the only job he ever wanted, first as head football coach and then as athletic director at the University of Arkansas. An optimist and a visionary who looked at life with an attitude of gratitude, Broyles lived life Broyles provided color Frank and Barbara Broyles beam with their commentary for ABC’s coverage of to the fullest for 92 years. four sons and newborn twin daughters college football in the 1970’s Coach Broyles’ legacy lives on through the countless lives he impacted on and off the field, through the Broyles Foundation and their efforts to support Alzheimer’s caregivers at no cost, and through the Broyles Award nominees, finalists, and winners that continue Broyles and Darrell Royal meet at to impact the world of college athletics and midfield after the 1969 #1 Texas vs. -

Events and Information F O R T H E Tc U Community

EVENTS AND INFORMATION F O R T H E TC U COMMUNITY VO L. 1 2 N 0. 3 8 J U L Y 3 0, 2 0 0 7 Brite president D. Newell Here are the nation's top-1 O coaches according to SI.corn's Stewart Mandel. EVENTS Williams chosen moderator of 1. Pete Carroll, USC 2. Urban Meyer, Florida Today-Aug. 3 Christian Church nationwide Frog Camp, Alpine B.* DR. D. NEWELL WILLIAMS WAS INSTALLED 3. Jim Tressel, Ohio State as moderator of the Christian Church (Disciples 4. Mack Brown, Texas JulY. 31-Aug. 2 Neil Dougherty's Basketball Day Camp II, 8:30 5. Bob Stoops, Oklahoma of Christ) for 2007-2009 during the group's a.m.-noon: entering Grades 1-4; 1-4:30 p.m.: national General Assembly meeting in Fort Worth 6. Frank Beamer, Virginia Tech entering Grades 5-8, Schollmaier Basketball Complex. Call ext. 7968 for more information. last week. Newell has been president of Brite 7. Jim Grobe, Wake Forest Divinity School atTCU since 2003. He also serves 8. Rich Rodriguez, West Virginia Aug. 1 as professor of modern and American church 9. Mark Richt, Georgia Crucial Conversations Reunion Breakfast, 8- 9:30 a.m., HR Conference Room.** history at Brite. 10. Gary Patterson, TCU + An author and editor, Newell previously taught Aug.2 Focus on Wellness Luncheon, Powerful Super at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis Department of social work Foods presented by Allison Reyna, 11 :30 a.m.- where he also served as vice president and dean 1 p.m., Bass Living Room.** during the 1990s. -

David Cutcliffe Named Walter Camp 2013 Coach of the Year

For Immediate Release: December 5, 2013 Contact: Al Carbone (203) 671-4421 - Follow us on Twitter @WalterCampFF Duke’s David Cutcliffe Named Walter Camp 2013 Coach of the Year NEW HAVEN, CT – David Cutcliffe, head coach of the Atlantic Coast Conference Coastal Division champion Duke University Blue Devils, has been named the Walter Camp 2013 Coach of the Year. The Walter Camp Coach of the Year is selected by the nation’s 125 Football Bowl Subdivision head coaches and sports information directors. Cutcliffe is the first Duke coach to receive the award, and the first honoree from the ACC since 2001 (Ralph Friedgen, Maryland). Under Cutcliffe’s direction, the 20th-ranked Blue Devils have set a school record with 10 victories and earned their first-ever berth in the Dr. Pepper ACC Championship Game. Duke clinched the Coastal Division title and championship game berth with a 27-25 victory over in-state rival North Carolina on November 30. Duke (10-2, 6-2 in the Coastal Division) will face top-ranked Florida State (12-0) on Saturday, December 7 in Charlotte, N.C. The Blue Devils enter the game with an eight-game winning streak – the program’s longest since 1941. In addition, the Blue Devils cracked the BCS standings for the first time this season, and were a perfect 4-0 in the month of November (after going 1-19 in the month from 2008 to 2012). Cutcliffe was hired as Duke’s 21st coach on December 15, 2007. Last season, he led the high- scoring Blue Devils to a school record 410 points (31.5 points per game) and a berth in the Belk Bowl – the program’s first bowl appearance since 1994. -

African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: a Qualitative Study on Turning Points

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points Thaddeus Rivers University of Central Florida Part of the Educational Leadership Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rivers, Thaddeus, "African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1469. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1469 AFRICAN AMERICAN HEAD FOOTBALL COACHES AT DIVISION I FBS SCHOOLS: A QUALITATIVE STUDY ON TURNING POINTS by THADDEUS A. RIVERS B.S. University of Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Child, Family and Community Sciences in the College of Education and Human Performance at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2015 Major Professor: Rosa Cintrón © 2015 Thaddeus A. Rivers ii ABSTRACT This dissertation was centered on how the theory ‘turning points’ explained African American coaches ascension to Head Football Coach at a NCAA Division I FBS school. This work (1) identified traits and characteristics coaches felt they needed in order to become a head coach and (2) described the significant events and people (turning points) in their lives that have influenced their career. -

2014 CLEMSON TIGERS Football Clemson (22 AP, 24 USA) Vs

2014 CLEMSON TIGERS Football Clemson (22 AP, 24 USA) vs. Florida State (1 AP, 1 USA) Clemson Tigers Florida State Seminoles Record, 2014 .............................................1-1, 0-0 ACC Record, 2014 .........................................2-0, 0-0 in ACC Saturday, September 20, 2014 Location ......................................................Clemson, SC Location ..................................................Talahassee, Fla Kickoff: 8:18 PM Colors .............................. Clemson Orange and Regalia Colors .......................................................Garnet & Gold Doak Campbell Stadium Enrollment ............................................................20,768 Enrollment ............................................................41,477 Athletic Director ........Dan Radakovich (Indiana, PA, ‘80) Tallahassee, FL Athletic Director ............... Stan Wilcox (Notre Dame ‘81) Head Coach .....................Dabo Swinney, Alabama ‘93 Head Coach ..................... Jimbo Fisher(Samford ‘87) Clemson Record/6th full year) ..................... 52-24 (.684) School Record ..................................47-10 (5th season) Television : ABC Home Record ............................................. 33-6 (.846) Overall ............................................47-10 (5th season) (Chris Fowler, Kirk Herbstreit, Heather Cox) Away Record ............................................ 14-14 (.500) Offensive Coordinator: .......................Lawrence Dawsey, Neutral Record ........................................................5-4 -

Illinois ... Football Guide

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign !~he Quad s the :enter of :ampus ife 3 . H«H» H 1 i % UI 6 U= tiii L L,._ L-'IA-OHAMPAIGK The 1990 Illinois Football Media Guide • The University of Illinois . • A 100-year Tradition, continued ~> The University at a Glance 118 Chronology 4 President Stanley Ikenberrv • The Athletes . 4 Chancellor Morton Weir 122 Consensus All-American/ 5 UI Board of Trustees All-Big Ten 6 Academics 124 Football Captains/ " Life on Campus Most Valuable Players • The Division of 125 All-Stars Intercollegiate Athletics 127 Academic All-Americans/ 10 A Brief History Academic All-Big Ten 11 Football Facilities 128 Hall of Fame Winners 12 John Mackovic 129 Silver Football Award 10 Assistant Coaches 130 Fighting Illini in the 20 D.I.A. Staff Heisman Voting • 1990 Outlook... 131 Bruce Capel Award 28 Alpha/Numerical Outlook 132 Illini in the NFL 30 1990 Outlook • Statistical Highlights 34 1990 Fighting Illini 134 V early Statistical Leaders • 1990 Opponents at a Glance 136 Individual Records-Offense 64 Opponent Previews 143 Individual Records-Defense All-Time Record vs. Opponents 41 NCAA Records 75 UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 78 UI Travel Plans/ 145 Freshman /Single-Play/ ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN Opponent Directory Regular Season UNIVERSITY OF responsible for its charging this material is • A Look back at the 1989 Season Team Records The person on or before theidue date. 146 Ail-Time Marks renewal or return to the library Sll 1989 Illinois Stats for is $125.00, $300.00 14, Top Performances minimum fee for a lost item 82 1989 Big Ten Stats The 149 Television Appearances journals. -

All In: What It Takes to Be the Best Copyright © 2011 by Gene Chizik

TYNDALE HOUSE PUBLISHERS, INC. CAROL STREAM, ILLINOIS Visit Tyndale online at www.tyndale.com. TYNDALE and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. All In: What It Takes to Be the Best Copyright © 2011 by Gene Chizik. All rights reserved. Front and back cover photographs copyright © by Todd J. Van Emst/Auburn Athletics. All rights reserved. Back cover photograph of coach Chizik with arms raised copyright © by Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images. All rights reserved. First six interior photographs are from the Chizik family collection and used with permission. All other interior photographs copyright © by Todd Van Emst/Auburn Athletics. All rights reserved. Author photograph of David Thomas copyright © 2009 by Sharon Ellman Photography. All rights reserved. Designed by Daniel Farrell Edited by Stephanie Voiland Published in association with the literary agency of Working Title Agency LLC, Spring Hill, TN. Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004, 2007 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked NIV are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version,® NIV.® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.TM Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chizik, Gene. All in : what it takes to be the best / Gene Chizik with David Thomas. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-4143-6435-3 (hc) 1. Success—Religious aspects—Christianity. 2. Chizik, Gene. 3. Football fans—Religious life. -

Tcu-Smu Series

FROG HISTORY 2008 TCU FOOTBALL TCU FOOTBALL THROUGH THE AGES 4General TCU is ready to embark upon its 112th year of Horned Frog football. Through all the years, with the ex cep tion of 1900, Purple ballclubs have com pet ed on an or ga nized basis. Even during the war years, as well as through the Great Depres sion, each fall Horned Frog football squads have done bat tle on the gridiron each fall. 4BEGINNINGS The newfangled game of foot ball, created in the East, made a quiet and un offcial ap pear ance on the TCU campus (AddRan College as it was then known and lo cat ed in Waco, Tex as, or nearby Thorp Spring) in the fall of 1896. It was then that sev er al of the col lege’s more ro bust stu dents, along with the en thu si as tic sup port of a cou ple of young “profs,” Addison Clark, Jr., and A.C. Easley, band ed to gether to form a team. Three games were ac tu al ly played that season ... all af ter Thanks giv ing. The first con test was an 86 vic to ry over Toby’s Busi ness College of Waco and the other two games were with the Houston Heavy weights, a town team. By 1897 the new sport had progressed and AddRan enlisted its first coach, Joe J. Field, to direct the team. Field’s ballclub won three games that autumn, including a first victory over Texas A&M. The only loss was to the Univer si ty of Tex as, 1810. -

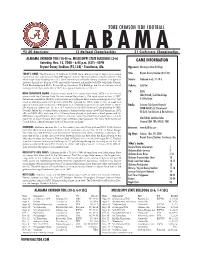

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky.