Folklife Center News, Volume 32, #3&4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WNYC Schedule 12.14.17

Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday 93.9 FM AM 820 93.9 FM AM 820 93.9 FM AM 820 5:00 AM 5:00 AM BBC World Service 5:00 AM BBC World Service BBC World Service BBC World Service 5:30 BBC World Service 5:30 The Capitol Connection 5:30 6:00 Morning Edition 6:00 6:00 Reveal Left, Right & Center The Splendid Table The Capitol Pressroom 6:30 Morning Edition 6:30 6:30 7:00 Marketplace Morning Rpt. 6:50 & 8:50 7:00 7:00 On the Media Innovation Hub On Being Latino USA 7:30 Money Talking: Friday, 5:50 & 7:50 Marketplace Morning Rpt. 6:50 & 8:50 7:30 7:30 8:00 Money Talking: Friday, 5:50 & 7:50 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 Weekend Edition Weekend Edition 8:30 9:00 9:00 Saturday Weekend Edition Sunday Weekend Edition 9:00 BBC Newshour The Takeaway 9:30 9:30 Saturday Sunday 9:30 10:00 10:00 The New Yorker 10:00 On the Media 10:30 10:30 Radio Hour 10:30 The Brian Lehrer Show The Brian Lehrer Show 11:00 11:00 Wait, Wait Wait, Wait 11:00 Studio 360 Specials 11:30 11:30 Don't Tell Me Don't Tell Me 11:30 NOON NOON The New Yorker NOON Radiolab Ask Me Another 12:30 PM 12:30 PM Radio Hour 12:30 PM The Leonard Lopate Show The Leonard Lopate Show 1:00 1:00 Planet Money 1:00 This American Life This American Life 1:30 1:30 How I Built This The Sunday Show 1:30 2:00 Fresh Air (Monday-Thursday) 2:00 Jonathan Schwartz 2:00 1A The Moth Freakonomics Radio On Being 2:30 Science Friday (Friday) 2:30 2:30 3:00 3:00 3:00 The Takeaway BBC Newshour Ask Me Another Studio 360 On the Media 3:30 3:30 3:30 4:00 4:00 Wait, Wait 4:00 Freakonomics Radio BBC Newshour BBC Newshour 4:30 4:30 Don't -

April May June

May 2005 vol 40, No.5 April 30 Sat Songs and Letters of the Spanish Civil War, co-sponsored with and at the Peoples’ Voice Cafe May 1 Sun Sea Music Concert: Dan Milner, Bob Conroy & Norm Pederson + NY Packet; 3pm South St.Melville Gallery 4WedFolk Open Sing; Ethical Culture Soc., Brooklyn, 7pm 9 Mon NYPFMC Exec. Board Meeting 7:15pm at the club office, 450 7th Ave, #972D (34-35 St), info 1-718-575-1906 14 Sat Chantey Sing at Seamen’s Church Institute, 8pm 15 Sun Sacred Harp Singing at St. Bart’s, Manhattan; 2:30 pm 19 Thur Riverdale Sing, 7:30-10pm, Riverdale Prsby. Church, Bronx 20 Fri Bill Staines, 8pm at Advent Church ☺ 21 Sat For The Love of Pete; at Community Church 22 Sun Gospel & Sacred Harp Sing, 3pm: location TBA 22 Sun Balkan Singing Workshop w/ Erica Weiss in Manhattan 22 Sun Sunnyside Song Circle in Queens; 2-6pm 27-30 Spring Folk Music Weekend --see flyer in centerfold June 1WedFolk Open Sing; Ethical Culture Soc., Brooklyn, 7pm 2 Thur Newsletter Mailing; at Club office, 450 7th Ave, #972, 7 pm 7 Tue Sea Music Concert: Mick Moloney + NY Packet; 6pm South Street Seaport Melville Gallery 11 Sat Chantey Sing at Seamen’s Church Institute, 8pm 13 Mon NYPFMC Exec. Board Meeting 7:15pm at the club office, 450 7th Ave, #972D (34-35 St), info 1-718-575-1906 14 Tue Sea Music Concert: The NexTradition + NY Packet; 6pm 16 Thur: Sara Grey & Kieron Means; location to be announced 19 Sun Sacred Harp Singing at St. -

1 Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Regents Of

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY SYSTEM OF GEORGIA HELD AT 270 Washington St., S.W. Atlanta, Georgia November 19 and 20, 2002 CALL TO ORDER The Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia met on Tuesday, November 19 and Wednesday, November 20, 2002, in the Board Room, room 7007, 270 Washington St., S.W., seventh floor. The Chair of the Board, Regent Joe Frank Harris, called the meeting to order at 1:00 p.m. on Tuesday, November 19, 2002. Present on Tuesday, in addition to Chair Harris, were Vice Chair James D. Yancey and Regents Hugh A. Carter, Jr., Connie Cater, William H. Cleveland, Michael J. Coles, Hilton H. Howell, Jr., George M. D. (John) Hunt III, Donald M. Leebern, Jr., Allene H. Magill, Elridge W. McMillan, Martin W. NeSmith, Wanda Yancey Rodwell, J. Timothy Shelnut, Glenn S. White, and Joel O. Wooten, Jr. Chair Harris announced that the Regents had a very productive retreat at the Jolley Lodge on Monday, November 18, 2002, and he thanked the Regents who made time in their schedules to attend. Chair Harris said that the Regents had heard the tragic news regarding the death of William H. (Bill) Weber III, husband of the Secretary to the Board, Gail S. Weber, and that he wanted to begin this meeting with a few words. He stated that Ms. Weber is the Regents’ colleague, friend, and family. Mr. Weber was also dedicated to higher education. He earned his doctorate in Economics from Columbia University and had an esteemed career as a professor at Agnes Scott College and Lyon College in Arkansas. -

Tacoma Refuses to Lose

TACOMA REFUSES TO LOSE werefusetolose.org TRUTH IS ESSENTIAL. Introducing the We TRUTH IS POWER. Refuse to Lose Series TRUTH IS HEALING. AN EDUCATION FIRST PRODUCTION The We Refuse to Lose series explores what cradle-to-career initiatives across the country are doing to improve outcomes for students of color TRUTH FOR TACOMA. and those experiencing poverty. The series profiles five communities— Buffalo, Chattanooga, Dallas, the Rio Grande Valley and Tacoma —that are working to close racial gaps for students journeying from early education TRUTH IS COURAGE. to careers. A majority of these students come from populations that have been historically oppressed and marginalized through poorly resourced schools, employment, housing and loan discrimination, police violence, a TRUTH IS URGENT. disproportionate criminal justice system and harsh immigration policies. Since early 2019, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has supported these five community partnerships and convened their leaders as a learning community. It commissioned Education First to write this series TRUTH IS JUSTICE. to share how these communities refuse to lose their children and youth to the effects of systemic racism and a new and formidable foe —COVID-19. TRUTH IS YOURS. TRUTH IS NOW. Cover Photo: Courtesy of Deeper Learning 2 WE REFUSE TO LOSE TACOMA PROFILE 01 LYLE QUASIM, COMMUNITY LEADER school for the Black Panther Party, defending Native With the help of Graduate American fishing rights and serving as a college president and cabinet member as the head of state Tacoma, the city’s cradle-to- agencies for two governors, Quasim sits behind his home desk for a virtual interview. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

The Digital Story

THE DIGITAL STORY: GIVING VOICE TO THE UNHEARD IN WASHINGTON, D.C. A REPORT OF THE COMMUNITY VOICE PROJECT APRIL 2018 NINA SHAPIRO-PERL, PHD WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY BRIGID MAHER, AMBERLY ALENE ELLIS, AND MAREK CABRERA ABOUT THE PROJECT The Digital Story: Giving Voice to the Unheard in Washington, D.C. In 2008, with the support of the American University School of Communication, the AU Anthropology Department, and the Surdna Foundation, American University began a community storytelling initiative, the Community Voice Project (CVP). Under the leadership of SOC Dean Emeritus Larry Kirkman, Professors Nina Shapiro-Perl and Angie Chuang set out to capture stories of the unseen and unheard Washington, D.C., through filmmaking and reporting, while helping a new generation of social documentarians through a training process. Over the past decade, the Community Voice Project, directed by AU School of Communication Filmmaker-in-Residence Nina Shapiro-Perl, has produced more than 80 films and digital stories. These stories, created in collaboration with over 25 community organizations, have brought the voice and visibility of underserved groups to the public while providing students and community members with transformative and practical experiences. About the Center for Media & Social Impact The Center for Media & Social Impact (CMSI) at American University’s School of Communication, based in Washington, D.C., is a research center and innovation lab that creates, studies and showcases media for social impact. Focusing on independent, documentary, entertainment and public media, CMSI bridges boundaries between scholars, producers and communication practitioners who work across media production, media impact, public policy and audience engagement. -

"Or This Whole Affair Is a Failure": a Special Treasury Agent's Observations of the Port Royal Experiment, Port Royal, South Carolina, April to May, 1862

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 "Or this whole affair is a failure": a special treasury agent's observations of the Port Royal Experiment, Port Royal, South Carolina, April to May, 1862 Michael Edward Scott Emett [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Emett, Michael Edward Scott, ""Or this whole affair is a failure": a special treasury agent's observations of the Port Royal Experiment, Port Royal, South Carolina, April to May, 1862" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1028. https://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1028 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “OR THIS WHOLE AFFAIR IS A FAILURE”: A SPECIAL TREASURY AGENT’S OBSERVATIONS OF THE PORT ROYAL EXPERIMENT, PORT ROYAL, SOUTH CAROLINA, APRIL TO MAY, 1862 A thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Michael Edward Scott Emett Approved by Dr. Michael Woods, Committee Chairperson Dr. Robert Deal Dr. Tyler Parry Marshall University July 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Michael Edward Scott Emett, affirm that the thesis, "Or This Whole ffiir Is A Failure": A Special Treasury Agent's Observations of the Port Royal Experiment, Port Royal, South Carolins, April to May, 1865, meets dre high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the Masters of History Program and the College of Liberal Arts. -

Life on the Sea Islands, 1864, Charlotte Forten

Life on the Sea Islands, 1864 Charlotte Forten Introduction The Civil War began just off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina in April, 1861. By November, the United States Army controlled the South Carolina coast including the Sea Islands, a collection of barrier islands stretching 185 miles. The Guale Indians lived on the Islands for hundreds of years before the Spanish colonized the southeastern coast of North America during the sixteenth century. Mainland South Carolina became a British colony in 1663, and unlike neighboring Virginia, was founded as a slave society. South Carolina had the largest population of enslaved people as a colony and later, a state. In fact, South Carolina still had the largest population of enslaved people when the Civil War broke out in 1861. The Spanish ceded the Sea Islands to the British following the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. The low-tides and fertile soil of the Sea Islands made the them ideal for cultivating rice and sugar, and later, cotton. The rice plantations in the Sea Islands were some of the largest and most lucrative in South. Rice planters were the wealthiest men in America, primarily because enslaved bodies were the most valuable property before the Civil War. Rice plantations relied on hundreds of enslaved people. Several Sea Island plantations had over one thousand enslaved people. Enslaved people on the Sea Islands essentially lived in small towns, where they developed their own distinct identity, culture, and language known as Gullah. The Gullah language was rooted in the Creek language of the Guale Indians, but included elements of Spanish, French, English, African, and Afro-Caribbean languages. -

A Structural Analysis of Personal Experience Narratives, the Federal Writers‘ Project to Storycorps

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE: A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL EXPERIENCE NARRATIVES, THE FEDERAL WRITERS‘ PROJECT TO STORYCORPS by Megan M. Dickson B.A. May 2007, Utah State University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 16, 2010 Thesis directed by John Michael Vlach Professor of American Studies and of Anthropology © Copyright 2010 by Megan Marie Dickson All rights reserved ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to the experiences we each have and share every day— in the park, over the phone, and sometimes even to a government employee (circa 1937), or with a loved one in a cozy StoryCorps sound booth in New York City. To my husband— Perry Dickson—without you, your love and strength, your championing and cheerleading this story would never have been possible. To my parents—Mona and Ken Farnsworth, and Robin Dickson—thank you for your unending love, support, encouragement, and belief. To my son Parker, whose story has only just begun, your vigor and verve for life already bring constant adventure and joy beyond measure. iii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge and thank the faculty and staff of the American Studies department at The George Washington University. A special thanks to Maureen Kentoff—the most fabulous muse in American Studies Executive Assistant history for helping to navigate the sometime frightful waters of university protocol, and sharing ways to succeed as a non-traditional student; John Michael Vlach—my faithful advisor; Melanie McAlister—Director of Graduate Studies who administered my comprehensive examination; Phyllis Palmer—a woman whose enthusiasm and intellectual spark lit up an otherwise apathetic paper proposal; and Thomas Guglielmo, Chad Heap, Terry Murphy, and Elizabeth Anker—for their teaching prowess and academic acumen. -

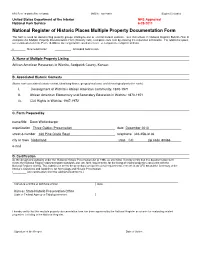

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior NPS Approved National Park Service 6-28-2011 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing African American Resources in Wichita, Sedgwick County, Kansas B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. Development of Wichita’s African American Community: 1870-1971 II. African American Elementary and Secondary Education in Wichita: 1870-1971 III. Civil Rights in Wichita: 1947-1972 C. Form Prepared by name/title Deon Wolfenbarger organization Three Gables Preservation date December 2010 street & number 320 Pine Glade Road telephone 303-258-3136 city or town Nederland state CO zip code 80466 e-mail D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Folklife Sourcebook: a Directory of Folklife Resources in the United States

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 380 257 RC 019 998 AUTHOR Bartis, Peter T.; Glatt, Hillary TITLE Folklife Sourcebook: A Directory of Folklife Resources in the United States. Second Edition. Publications of the American Folklife Center, No. 14. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. American Folklife Center. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0521-3 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 172p.; For the first edition, see ED 285 813. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, P.O. Box 371954, Pittsburgh, PA 15250-7954 ($11, include stock no. S/N 030-001-00152-1 or U.S. Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-93280. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *College Programs; Cultural Education; Cultural Maintenance; Elementary Secondary Education; *Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Library Collections; *Organizations (Groups); *Primary Sources; Private Agencies; Public Agencies; *Publications; Rural Education IDENTIFIERS Ethnomusicology; *Folklorists; Folk Music ABSTRACT This directory lists professional folklore networks and other resources involved in folklife programming in the arts and social sciences, public programs, and educational institutions. The directory covers:(1) federal agencies; (2) folklife programming in public agencies and organizations, by state; (3)a listing by state of archives and special collections of folklore, folklife, and ethnomusicology, including date of establishment, access, research facilities, services, -

Ukulele Club of Santa Cruz Songbook Part 2

Introduction D7 G D7 G 67 C G Honolulu Baby, where'd you get those eyes D7 G G7 And that dark complexion, I idolize C G Honolulu Baby, where'd you get that style D7 G G7 HHoonnoolluulluu BBaabbyy Those pretty red lips, that sunny smile Music and lyrics by T. Marvin Hatley C G October 1933 for "Sons of the Desert" Neath palm trees swaying, at Waikiki starring Laurel and Hardy D7 G G7 Ukulele Club of Santa Cruz February 2004 Honolulu Baby, you're the one for me D7 G C G Honolulu Baby, when you start to sway D7 G G7 All the men go crazy, they seem to say C G Honolulu Baby, where'd you get those eyes D7 G G7 And that dark complexion, I idolize C G 7 C G Honolulu Baby, where'd you get that style D7 G G7 Those pretty red lips, that sunny smile C G Neath palm trees swaying, at Waikiki D7 G G7 Honolulu Baby, you're the one for me C G Honolulu Baby, at Waikiki D7 G G7 Honolulu Baby, you're the one for me D7 G G7 Honolulu Baby, you're the one for me "...the real music's in your mind. All the instruments are just mechanics." --- Marvin Hatley, composer of "Honolulu Baby" End with D7 G D7 G No mention of Laurel and Hardy music is complete without a nod to Hatley's immortal "Honolulu Baby" from the Boys' 1933 feature, SONS OF THE DESERT. Used in the big convention scene where Stan and Ollie share their subterfuge with fellow Son Charley Chase, "Honolulu Baby" comes off as both a typical "Hollywood Production Number" and a gentle satire of the same.