Thesis Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montréal's Gay Village

Produced By: Montréal’s Gay Village Welcoming and Increasing LGBT Visitors March, 2016 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ÉTUDE SUR LE VILLAGE GAI DE MONTRÉAL Partenariat entre la SDC du Village, la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec › La Société de développement commercial du Village et ses fiers partenaires financiers, que sont la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec, sont heureux de présenter cette étude réalisée par la firme Community Marketing & Insights. › Ce rapport présente les résultats d’un sondage réalisé auprès de la communauté LGBT du nord‐est des États‐ Unis (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, État de New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvanie, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginie, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois), du Canada (Ontario et Colombie‐Britannique) et de l’Europe francophone (France, Belgique, Suisse). Il dresse un portrait des intérêts des touristes LGBT et de leurs appréciations et perceptions du Village gai de Montréal. › La première section fait ressortir certaines constatations clés alors que la suite présente les données recueillies et offre une analyse plus en détail. Entre autres, l’appréciation des touristes qui ont visité Montréal et la perception de ceux qui n’en n’ont pas eu l’occasion. › L’objectif de ce sondage est de mieux outiller la SDC du Village dans ses démarches de promotion auprès des touristes LGBT. 2 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ABOUT CMI OVER 20 YEARS OF LGBT INSIGHTS › Community Marketing & Insights (CMI) has been conducting LGBT consumer research for over 20 years. Our practice includes online surveys, in‐depth interviews, intercepts, focus groups (on‐site and online), and advisory boards in North America and Europe. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

The Reconstruction of Gender and Sexuality in a Drag Show*

DUCT TAPE, EYELINER, AND HIGH HEELS: THE RECONSTRUCTION OF GENDER AND SEXUALITY IN A DRAG SHOW* Rebecca Hanson University of Montevallo Montevallo, Alabama Abstract. “Gender blending” is found on every continent; the Hijras in India, the female husbands in Navajo society, and the travestis in Brazil exemplify so-called “third genders.” The American version of a third gender may be drag queen performers, who confound, confuse, and directly challenge commonly held notions about the stability and concrete nature of both gender and sexuality. Drag queens suggest that specific gender performances are illusions that require time and effort to produce. While it is easy to dismiss drag shows as farcical entertainment, what is conveyed through comedic expression is often political, may be used as social critique, and can be indicative of social values. Drag shows present a protest against commonly held beliefs about the natural, binary nature of gender and sexuality systems, and they challenge compulsive heterosexuality. This paper presents the results of my observational study of drag queens. In it, I describe a “routine” drag show performance and some of the interactions and scripts that occur between the performers and audience members. I propose that drag performers make dichotomous American conceptions of sexuality and gender problematical, and they redefine homosexuality and transgenderism for at least some audience members. * I would like to thank Dr. Stephen Parker for all of his support during the writing of this paper. Without his advice and mentoring I could never have started or finished this research. “Gender blending” is found on every continent. The Hijras in India, the female husbands in Navajo society, and the travestis in Brazil are just a few examples of peoples and practices that have been the subjects for “third gender” studies. -

Shifting the Media Narrative on Transgender Homicides

w Training, Consultation & Research to Accelerate Acceptance More SHIFTING THE MEDIA Than NARRATIVE ON TRANSGENDER HOMICIDES a Number MARCH 2018 PB 1 Foreword 03 An Open Letter to Media 04 Reporting Tip Sheet 05 Case Studies 06 Spokespeople Speak Out 08 2017 Data Findings 10 In Memorium 11 Additional Resources 14 References 15 AUTHORS Nick Adams, Director of Transgender Media and Representation; Arielle Gordon, News and Rapid Response Intern; MJ Okma, Associate Director of News and Rapid Response; Sue Yacka-Bible, Communications Director DATA COLLECTION Arielle Gordon, News and Rapid Response Intern; MJ Okma, Associate Director of News and Rapid Response; Sue Yacka-Bible, Communications Director DATA ANALYSIS Arielle Gordon, News and Rapid Response Intern; MJ Okma, Associate Director of News and Rapid Response DESIGN Morgan Alan, Design and Multimedia Manager 2 3 This report is being released at a time in our current political climate where LGBTQ acceptance is slipping in the U.S. and anti-LGBTQ discrimination is on the rise. GLAAD and This report documents The Harris Poll’s most recent Accelerating Acceptance report found that 55 percent of LGBTQ adults reported experiencing the epidemic of anti- discrimination because of their sexual orientation or gender transgender violence in identity – a disturbing 11% rise from last year. 2017, and serves as a companion to GLAAD’s In our online resource for journalist and advocates, the Trump tip sheet Doubly Accountability Project, GLAAD has recorded over 50 explicit attacks by the Trump Administration – many of which are Victimized: Reporting aimed at harming and erasing transgender people, including on Transgender an attempt to ban trans people from serving in the U.S. -

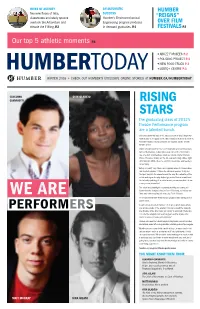

Humber Today in a Past Interview

HIVES OF ACTIVITY AN AUTOMATIC HUMBER Two new floors of labs, SUCCESS classrooms and study spaces Humber’s Electromechanical “REIGNS” overlook the Arboretum and Engineering program produces OVER FILM elevate the F Wing. P. 2 in-demand graduates. P. 4 FESTIVALS P. 3 Our top 5 athletic moments P. 4 + ABUZZ FOR BEES P.2 + POLICING PROJECT P.3 + NEW FOOD TRUCK P.3 + LGBTQ+ CENTRE P.3 WINTER 2016 • CHECK OUT HUMBER’S EXCLUSIVE ONLINE STORIES AT HUMBER.CA/HUMBERTODAY GIACOMO OYIN OLADEJO GIANNIOTTI RISING STARS The graduating class of 2012’s Theatre Performance program are a talented bunch. Giacomo Gianniotti was in the latest season of Grey’s Anatomy. Matt Murray is a regular on the ABC Family show Kevin from Work. And Oyin Oladejo and Sina Gilani are regulars on the Toronto theatre scene. Gilani is best known for his recent dramatic (and controversial) turn in the Buddies in Bad Times play The 20th of November. The one-man show features Gilani as school shooter Bastian Bosse. It’s based mainly on the 18-year-old’s blog entries, right until Nov. 20, 2006, when he shot 30 classmates and teachers in Germany. “Acting is a craft,” says Gilani, who originally came to Canada from Iran to study physics. “It takes the rehearsal process to try and find your way into the character and the play. The collective of the artists working on the play helped get inside Bastian's world and his twisted psychology. It is called a one-person show, but it is not a one-person production.” The actor and playwright is currently working on touring his Summerworks-featured play In Case of Nothing, as well as two films and workshopping his new play Field of Reeds. -

Gay Subculture Identification: Training Counselors to Work with Gay Men

Article 22 Gay Subculture Identification: Training Counselors to Work With Gay Men Justin L. Maki Maki, Justin L., is a counselor education doctoral student at Auburn University. His research interests include counselor preparation and issues related to social justice and advocacy. Abstract Providing counseling services to gay men is considered an ethical practice in professional counseling. With the recent changes in the Defense of Marriage Act and legalization of gay marriage nationwide, it is safe to say that many Americans are more accepting of same-sex relationships than in the past. However, although societal attitudes are shifting towards affirmation of gay rights, division and discrimination, masculinity shaming, and within-group labeling between gay men has become more prevalent. To this point, gay men have been viewed as a homogeneous population, when the reality is that there are a variety of gay subcultures and significant differences between them. Knowledge of these subcultures benefits those in and out-of-group when they are recognized and understood. With an increase in gay men identifying with a subculture within the gay community, counselors need to be cognizant of these subcultures in their efforts to help gay men self-identify. An explanation of various gay male subcultures is provided for counselors, counseling supervisors, and counselor educators. Keywords: gay men, subculture, within-group discrimination, masculinity, labeling Providing professional counseling services and educating counselors-in-training to work with gay men is a fundamental responsibility of the counseling profession (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014). Although not all gay men utilizing counseling services are seeking services for problems relating to their sexual orientation identification (Liszcz & Yarhouse, 2005), it is important that counselors are educated on the ways in which gay men identify themselves and other gay men within their own community. -

Gender Identity • Expression

In New York City, it’s illegal to discriminate on the basis of gender identity and gender expression in the workplace, in public spaces, and in housing. The NYC Commission on Human Rights is committed to ensuring that transgender and gender non-conforming New Yorkers are treated with dignity and respect and without threat of discrimination or harassment. This means individuals GENDER GENDER have the right to: • Work and live free from discrimination IDENTITY EXPRESSION and harassment due to their gender One's internal, External representations of gender as identity/expression. deeply-held sense expressed through, for example, one's EXPRESSION • Use the bathroom or locker room most of one’s gender name, pronouns, clothing, haircut, consistent with their gender identity as male, female, behavior, voice, or body characteristics. • and/or expression without being or something else Society identifies these as masculine required to show “proof” of gender. entirely. A transgender and feminine, although what is • Be addressed with their preferred person is someone considered masculine and feminine pronouns and name without being whose gender identity changes over time and varies by culture. required to show “proof” of gender. does not match Many transgender people align their • Follow dress codes and grooming the sex they were gender expression with their gender standards consistent with their assigned at birth. identity, rather than the sex they were gender identity/expression. assigned at birth. Courtesy 101: IDENTITY GENDER • If you don't know what pronouns to use, ask. Be polite and respectful; if you use the wrong pronoun, apologize and move on. • Respect the terminology a transgender person uses to describe their identity. -

Speech Stereotypes of Female Sexuality by Auburn Lupine Barron

Speech Stereotypes of Female Sexuality by Auburn Lupine Barron-Lutzross A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Keith Johnson, Co-Chair Professor Susan Lin, Co-Chair Professor Justin Davidson Professor Mel Chen Spring 2018 © Copyright 2018 Auburn Lupine Barron-Lutzross All rights reserved Abstract Speech Stereotypes of Female Sexuality by Auburn Lupine Barron-Lutzross Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Keith Johnson, Co-Chair Professor Susan Lin, Co-Chair At its core, my dissertation addresses one primary question: What does it mean to sound like a lesbian? On the surface, this may seem a relatively simple question, but my work takes a broad perspective, approaching this single question from a multitude of perspectives. To do so I carried out a combination of experiments, interpreting the results through the Attention Weighted Schema Abstraction model that I developed. Following the introduction Chapter 2 lays out the AWSA model in the context of previous literature on stereotype conception and speech and sexuality. Chapter 3 presents the production experiment, which recorded speakers reading a series of single words and sentences and interviews discussing stereotypes of sexuality. Phonetic analysis showed that though speech did not vary categorically by sexual orientation, familiarity with Queer culture played a significant role in variation of speech rate and mean pitch. This pattern was only seen for straight and bisexual speakers, suggesting that lesbian stereotypes are used to present an affinity with Queer culture, which was further supported by the decrease or loss of their significance in interview speech. -

Bury Your Gays’

. Volume 15, Issue 1 May 2018 Toxic regulation: From TV’s code of practices to ‘#Bury Your Gays’ Kelsey Cameron, University of Pittsburgh, USA Abstract: In 2016, American television killed off many of its queer female characters. The frequency and pervasiveness of these deaths prompted outcry from fans, who took to digital platforms to protest ‘bury your gays,’ the narrative trope wherein queer death serves as a plot device. Scholars and critics have noted the positive aspects of the #BuryYourGays fan campaign, which raised awareness of damaging representational trends and money for the Trevor Project, a suicide prevention organization focused on LGBTQ youth. There has been less attention to the ties #BuryYourGays has to toxicity, however. Protests spilled over into ad hominem attacks, as fans wished violence upon the production staff responsible for queer character deaths. Using the death of The 100 character Lexa as a case study, this article argues that we should neither dismiss these toxic fan practices nor reduce them to a symptom of present-day fan entitlement. Rather, we must attend to the history that shapes contemporary antagonisms between producers and queer audiences – a history that dates back to television’s earliest efforts at content regulation. Approaching contemporary fandom through history makes clear that toxic fan practices are not simply a question of individual agency. Longstanding industry structures predispose queer fans and producers to toxic interactions. Keywords: queer fandom, The 100, television, regulation, ‘bury your gays’ Introduction In March of 2016, queer fans got angry at American television. This anger was both general and particular, grounded in long-simmering dissatisfaction with TV’s treatment of queer women and catalyzed by a wave of character deaths during the 2016 television season. -

The State of the Lesbian Bar: San Francisco Toasts to the End of an Era | Autostraddle

11/11/2014 The State of the Lesbian Bar: San Francisco Toasts To The End Of An Era | Autostraddle News, Entertainment, Opinion, Community and Girl-on-Girl Culture The State of the Lesbian Bar: San Francisco Toasts To The End Of An Era Posted by Robin on November 11, 2014 at 5:00am PST In Autostraddle’s The State of the Lesbian Bar, we’re taking a look at lesbian bars around the country as the possibility of extinction looms ever closer. If you’re in the Bay Area or used to live there, you probably heard the news that The Lexington Club has recently been sold, and will be closing in a few months. When it closes, San Francisco will be left with exactly zero dedicated lesbian bars in its city limits. Which sounds impossible. No lesbian bars? In one of the gay-friendliest cities in the country? The same city where America’s first lesbian bar, Mona’s 440 Club, opened in the mid-1930s? So I set out to investigate the State of the San Francisco Lesbian Bar. http://www.autostraddle.com/the-state-of-the-lesbian-bar-san-francisco-toasts-to-the-end-of-an-era-262072/ 1/12 11/11/2014 The State of the Lesbian Bar: San Francisco Toasts To The End Of An Era | Autostraddle The End of an Era For many folks in the Bay Area, the Lex was almost a rite of passage. It was their baby queer refuge, the place where they met a community of people just like them, where they found their lovers and their families. -

The Rhetorics of the Voltron: Legendary Defender Fandom

"FANS ARE GOING TO SEE IT ANY WAY THEY WANT": THE RHETORICS OF THE VOLTRON: LEGENDARY DEFENDER FANDOM Renee Ann Drouin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2021 Committee: Lee Nickoson, Advisor Salim A Elwazani Graduate Faculty Representative Neil Baird Montana Miller © 2021 Renee Ann Drouin All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Lee Nickoson, Advisor The following dissertation explores the rhetorics of a contentious online fan community, the Voltron: Legendary Defender fandom. The fandom is known for its diversity, as most in the fandom were either queer and/or female. Primarily, however, the fandom was infamous for a subsection of fans, antis, who performed online harassment, including blackmailing, stalking, sending death threats and child porn to other fans, and abusing the cast and crew. Their motivation was primarily shipping, the act of wanting two characters to enter a romantic relationship. Those who opposed their chosen ship were targets of harassment, despite their shared identity markers of female and/or queer. Inspired by ethnographically and autoethnography informed methods, I performed a survey of the Voltron: Legendary Defender fandom about their experiences with harassment and their feelings over the show’s universally panned conclusion. In implementing my research, I prioritized only using data given to me, a form of ethical consideration on how to best represent the trauma of others. Unfortunately, in performing this research, I became a target of harassment and altered my research trajectory. In response, I collected the various threats against me and used them to analyze online fandom harassment and the motivations of antis. -

Queer Tastes: an Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, Jacqueline Kristine, "Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 1021. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1021 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in English, 2010 May 2014 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _________________________ Dr. Lisa Hinrichsen Thesis Director _________________________ _________________________ Dr. Susan Marren Dr. Robert Cochran Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT Southern identities are undoubtedly influenced by the region’s foodways. However, the South tends to neglect and even to negate certain peoples and their identities. Women, especially lesbians, are often silenced within southern literature. Where Tennessee Williams and James Baldwin used literature to bridge gaps between gay men and the South, southern lesbian literature severely lacks a traceable history of such connections.