FULLTEXT01.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zfwtvol. 9 No. 3 (2017) 269-288

ZfWT Vol. 9 No. 3 (2017) 269-288 FEMINIST READING OF GOTHIC SUBCULTURE: EMPOWERMENT, LIBERATION, REAPPROPRIATION Mikhail PUSHKIN∗ Abstract: Shifting in and out of public eye ever since its original appearance in the 1980ies, Gothic subculture, music and aesthetics in their impressive variety have become a prominent established element in global media, art and culture. However, understanding of their relation to female gender and expression of femininity remains ambiguous, strongly influenced by stereotypes. Current research critically analyses various distinct types of Gothic subculture from feminist angle, and positively identifies its environment as female-friendly and empowering despite and even with the help of its strongly sexualized aesthetics. Although visually geared towards the male gaze, Gothic subcultural environment enables women to harness, rather than repress the power of attraction generated by such aesthetics. Key words: Subculture, Feminism, Gothic. INTRODUCTION Without a doubt, Gothic subculture is a much-tattered subject, being at the centre of both popular mass media with its gossip, consumerism and commercialization, as well as academia with diverse papers debasing, pigeonholing and even defending the subculture. Furthermore, even within the defined, feminist, angle, a thorough analysis of Gothic subculture would require a volume of doctoral dissertation to give the topic justice. This leaves one in a position of either summarizing and reiterating earlier research (a useful endeavour, however, bringing no fresh insight), or striving for a kind of fresh look made possible by the ever-changing eclectic ambivalent nature of the subculture. Current research takes the middle ground approach: touching upon earlier research only where relevant, providing a very general, yet necessary outlook on the contemporary Gothic subculture in its diversity, so as to elucidate its more relevant elements whilst focusing on the ways in which it empowers women. -

Baseball Caps

HILLS HATS WINTER LOOKBOOK 2019 TWEED HATS Eske Donegal English Luton Check English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2540 2541 Navy, Black, Olive Brown, Grey S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Herefordshire Check English Wiltshire Houndstooth English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2542 2544 Blue, Green Brown, Grey, Beige, Blue, Fawn S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Devon Houndstooth Swindon Houndstooth Lambswool Tweed Cheesecutter Lambswool English Tweed Cheesecutter 2552 2573 Blue, Rust Blue, Green, Wine, Fawn S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL 1 Chester Overcheck Hunston Overcheck Lambswool English Tweed Cheesecutter English Tweed Cheesecutter 2574 2554 Blue, Olive, Brown Black, Blue, Brown, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Saxilby Overcheck English Glencoe Overcheck Lambswool Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2567 2537 Brown, Green Green, Mustard S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Bingley Check Lambswool Bramford Houndstooth English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2551 2556 Olive, Blue Blue, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL 2 TWEED HATS Warrington Herringbone English Tweed Cheesecutter 2576 Charcoal, Brown, Khaki S, M, L, XL, XXL English Wool Tweed Patchwork Cheesecutter 300 Blue, Green, Brown S, M, L, XL, XXL Eske Donegal English Tweed 4 Piece Cheesecutter 2570 Black, Navy, Olive S, M, L, XL, XXL 3 Dartford Herringbone English Tweed 4 Piece Cheesecutter 2570 Black, Brown, Blue, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL Bingley Check English Tweed 7 Piece Cheesecutter 2571 Blue, Olive S, M, L, XL, XXL Warrington Herringbone -

Spring Summer 2020 Vienna

SPRING SUMMER 2020 VIENNA What exactly is „Viennese Style“? The typical Was ist denn jetzt eigentlich dieser Wiener Stil? Viennese je-ne-sais-quoi, which has gained a Dieses typisch Wienerische, das längst eine world-wide reputation? In our Spring/Summer 2020 Weltkarriere hingelegt hat? Um nichts Geringeres collection we did our utmost to try and unearth this. als das herauszufinden, ging es in der Kollektion Did we find a succinct answer? Unfortunately not! Frühling/Sommer 2020. Haben wir eine schlüssige Vienna is many things, maybe even too many. Antwort darauf gefunden? Leider nein! But above all it is a “melange” – a blend of Wien ist Vieles, vielleicht sogar zu Vieles. Vor allem different influences and style directions, which, aber ist es eine „Melange“ unterschiedlichster when mixed together just so, result in something Einflüsse und Stilrichtungen, die in einem ganz typically Viennese. This is a fine balance between bestimmten Mischverhältnis eben Wienerisch simplicity and opulence, patina and gloss, art ergeben. Das spielt sich zwischen Schlichtheit und nouveau and social housing, superficiality and Opulenz ab, Patina und Hochglanz, Jugendstil skilful understatement. And generally between east und Gemeinde bau, Oberfläche und Understatement. and west, north and south – and we are right at Und überhaupt zwischen Westen und Osten, Norden the epicentre. Exuberant, completely over the top und Süden – und wir mittendrin. Überbordend and then again there is total clarity. Decorations, und dann wieder ganz klar. Ornamente, Rüschen, frills, fraying or their entire absence – this is the Fransen und deren Abwesenheit – das ist die Mühlbauer Spring/Summer 2020 collection. Mühlbauer- Kollektion Frühling/Sommer 2020. -

Hered White Frame for 5X7 Photo, 4X6 Slide 30

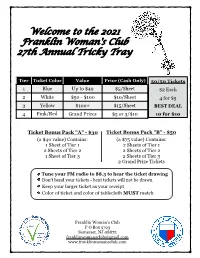

Welcome to the 2021 Franklin Woman's Club 27th Annual Tricky Tray Tier Ticket Color Value Price (Cash Only) 50/50 Tickets 1 Blue Up to $49 $5/Sheet $2 Each 2 White $50 - $100 $10/Sheet 4 for $5 3 Yellow $100+ $15/Sheet BEST DEAL 4 Pink/Red Grand Prizes $5 or 3/$10 10 for $10 Ticket Bonus Pack "A" - $30 Ticket Bonus Pack "B" - $50 (a $40 value) Contains: (a $75 value) Contains: 1 Sheet of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 2 2 Sheets of Tier 2 1 Sheet of Tier 3 2 Sheets of Tier 3 2 Grand Prize Tickets Tune your FM radio to 88.3 to hear the ticket drawing Don't bend your tickets - bent tickets will not be drawn Keep your larger ticket as your receipt Color of ticket and color of tablecloth MUST match Franklin Woman's Club P O Box 5793 Somerset, NJ 08875 [email protected] www.franklinwomansclub.com 11. Desk Set #1 Tier 1 Prizes 12. Desk Set #2 (Blue Tickets; Value up to $49) Black mesh letter sorter, pencil cup, clip holder and wastebasket 1. Cherry Blossom Spa Basket 13. Cake Pop Crush Japanese Cherry Blossom shower gel, bubble Cake Pops baking pan & accessories, cake pop bath, flower bath pouf, bath bombs, body and sticks, youth books “Cake Pop Crush” and hand lotion, more “Taking the Cake" 2. Friend Frame 14. Lunch Break "Friends" 6-opening photo collage picture frame FILA insulated lunch bag, pair of small snack for 2.25 X 3.25 inch photos containers 3. -

Autumn Winter 2021/22

AUTUMN WINTER 2021/22 cover: CLOCHE, wool felt soft, M21506, this page: CAP, lambskin, P21601, following page, left: BUCKET HAT, melusine felt, M21514, right: BUCKET HAT, melusine felt, M21515 AUTUMN WINTER 2021/22 BIG HUG Where have you gone, you intimate, stormy, friendly, romantic, comforting hugs? We have missed you so much. The autumn winter 2021/22 collection invites you to join it in a big, all-enveloping hug. The hats are fluffy and light as a feather, voluminous, as soft and padded as cotton wool. You can wrap yourself up in them, squeeze them heartily, literally crawl into them for comfort. In return they will hug you back and wrap themselves protectively around you. These are materials that invite cuddles, to feel, to sense, to lose ourselves in them. Because it’s simply impossible to keep your hands off cashmere loden, melusin felt, soft sherpa wool and thickly padded fabrics. The pieces in this collection are approachable, easy to grasp, and just as easy to experience and wear. This feels so good. Wo seid ihr geblieben, ihr innigen, stürmischen, freund- schaftlichen, romantischen, tröstenden Umarmungen? Wir haben euch so vermisst. Die Modelle der Kollektion Herbst Winter 2021/22 laden zu einer großen Umarmung ein. Sie sind flauschig und federleicht, watteweich gepolstert und mit Volumen gefüllt. Man kann sich darin einwickeln, sie herzhaft drücken, förmlich in sie hineinkriechen. Sie sind uns nahe und legen sich schützend um uns. Da sind Materialien, die zum Kuscheln einladen, zum Spüren, Fühlen, sich darin verlieren. Denn von Kaschmir- loden, Melusinfilz, weicher Sherpa-Wolle und dick gepolster- ten Stoffen kann man einfach nicht die Finger lassen. -

Aloha Hat Protect Delicate Infant Skin from the Sun’S Harsh Rays

2019 The Monterey, see page 6. The 2019 Collection THE “W” COLLECTION ............................................. 4 WOMEN ..................................................................... 24 PETITE ......................................................................... 42 EXTRAS ....................................................................... 43 MEN ............................................................................. 44 CHILDREN .................................................................. 54 Because life is meant Look for our sun icon throughout to be lived in color! the catalog to determine which hats are UPF 50+. These When we started Wallaroo 19 years ago, I was sure fabrics block 97.5% of the sun’s of our purpose — to craft sun-protective hats that ultraviolet rays. Please remember, make you look and feel great. Inspired by visits to my a Wallaroo hat only protects the skin husband's family in Australia — where the threat of skin it covers. Safeguard the rest of your body cancer has long been understood — I wanted to share by wearing sunglasses and sunscreen. that awareness far and wide. From our home base in Colorado, we draw inspiration The Skin Cancer Foundation from nature — the earthy tones of the Rocky Mountains recommends the material of every and the brilliant blue of the sunny skies. We focus Wallaroo hat with a UPF rating and on quality craftsmanship and functional, fashionable a 3" brim or wider as an effective designs so your Wallaroo hat can go with you on UV protectant. all your adventures. We want you to get out there — to play, hike, swim and explore — with complete confidence, knowing you're covered in style. Wallaroo Sun Protection Commitment: We promise that each year we will As a leader in our industry, we also think it's important donate 1% of our profits to skin to look beyond the bottom line. -

To View the 100Th Most Modern Object in Global Fashion History Report

Jessi Moonheart Global Fashion History 100th Object Final Paper The Maiden Who Was Born to Be Lolita- The Gothic Lolita Bible and its Significance as an Important Object in Fashion History Introduction “...‘I am a special maiden.’ It’s okay for you to think that you know. Even if there are strangers who look away and snicker at you because your skirt is too poufy, or because the ribbon adorning your hair is too big. You don’t have to let it bother you. Sure, it’s aggravating that there still are some confused people who see Gothic and Lolita as unemotional, cheap cosplay, but you should just remain confident and stand tall…. Cotton candy envelopes your heart. Scarlet roses bloom in your eyes, and the taste of honey forever spreads upon your tongue. Your hair is soft and your skin is smooth. You are a maiden who was born to be Lolita. You exist in a cocoon. The light of the sun and the glistening of the moon fall upon you there. You want to stay in there forever with your eyes closed. While you wish for that, the dreams that fall gently upon you there are woven like a sweet layer of powdered sugar…” -Excerpts from ‘Oh Maiden: Advance with a Sword and a Rose’ by Arika Takarano of Ali Project, Gothic & Lolita Bible US Winter 2009 The Gothic & Lolita Bible (also referred to as the GLB) was a quarterly Japanese “mook” that was first published in 2001 by Index Communications and was a spinoff of the magazine, Kera. -

The Vampire Archetype and the Steampunk Vamp Carina Maxfield

LiteraturaSubverting e Ética: the experiências Canon: The de leitura Vampire em contexto Archetype de ensino and the Steampunk Vamp Alexandra Isabel Lobo da Silva Lopes Carina Maxfield Dissertação de Mestrado em Estudos Portugueses Dissertação de Mestrado em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas Versão corrigida e melhorada após a sua defesa pública. Especialização em Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos Setembro, 2011 Novembro 2016 LiteraturaSubverting e Ética: the experiências Canon: The de leitura Vampire em contexto Archetype de ensino and the Steampunk Vamp Alexandra Isabel Lobo da Silva Lopes Carina Maxfield Dissertação de Mestrado em Estudos Portugueses Dissertação de Mestrado em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas Versão corrigida e melhorada após a sua defesa pública. Especialização em Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos Setembro, 2011 Novembro 2016 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas, realizada sob a orientação científica de Professora Doutora Iolanda Ramos. Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to Professor Iolanda Ramos for her time and patience in helping me complete this dissertation. I would also like to thank the school and several public libraries around Lisbon for lending me the space to complete my research. Finally, I would like to thank all of my friends, Vítor Arnaut, and my loving family for their complete physical and moral support through this at times challenging moment in my life. Subverter o Cânone: O Arquétipo do Vampiro e o ‘Steampunk Vamp’ Carina Maxfield Resumo Esta dissertação tem como objectivo analisar os diferentes modos em que o arquétipo do vampirismo se tem modificado das normas convencionais e como prevaleceu. -

The Victorian Age: a History of Dress, Textiles, and Accessories, 1819–1901

The Victorian Age: A History of Dress, Textiles, and Accessories, 1819–1901 International Conference of Dress Historians Friday, 25 October 2019 and Saturday, 26 October 2019 Convened By: The Association of Dress Historians www.dresshistorians.org Conference Venue: The Art Workers’ Guild 6 Queen Square London, WC1N 3AT England The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) supports and promotes the study and professional practice of dress and textile history. The ADH is proud to support scholarship in dress and textile history through its international conferences, the publication of The Journal of Dress History, prizes and awards for students and researchers, and ADH members’ events such as curators’ tours. The ADH is passionate about sharing knowledge. The mission of the ADH is to start conversations, encourage the exchange of ideas, and expose new and exciting research in the field. The ADH is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. As with all ADH publications, this conference programme is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. To view all ADH information, including events, Calls For Papers, and complete issues of The Journal of Dress History for free viewing and downloading, please visit www.dresshistorians.org. In the interest of the environment, this conference programme will not be printed on paper. We advise reading the programme digitally. Also in the interest of the environment, at the end of the conference please return plastic name badges to the name badge table, so the badges can be recycled. Thank you. If you are attending both days of the conference, you must retrieve your new name badge when you enter the venue on the second morning. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Crafting Women’s Narratives The Material Impact of Twenty-First Century Romance Fiction on Contemporary Steampunk Dress Shannon Marie Rollins A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Art) at The University of Edinburgh Edinburgh College of Art, School of Art September 2019 Rollins i ABSTRACT Science fiction author K.W. Jeter coined the term ‘steampunk’ in his 1987 letter to the editor of Locus magazine, using it to encompass the burgeoning literary trend of madcap ‘gonzo’-historical Victorian adventure novels. Since this watershed moment, steampunk has outgrown its original context to become a multimedia field of production including art, fashion, Do-It-Yourself projects, role-playing games, film, case-modified technology, convention culture, and cosplay alongside science fiction. And as steampunk creativity diversifies, the link between its material cultures and fiction becomes more nuanced; where the subculture began as an extension of the text in the 1990s, now it is the culture that redefines the fiction. -

Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915

Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915 Kimberly E. Hereford A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Susan Casteras, Chair Paul Berger Stuart Lingo Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art History ©Copyright 2015 Kimberly E. Hereford ii University of Washington Abstract Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915 Kimberly E. Hereford Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Susan Casteras Art History This dissertation examines representations in art of the Victorian woman in “altered states.” Though characterized in Victorian art in a number of ways, women are most commonly stereotyped as physically listless and mentally vacuous. The images examined show the Victorian female in a languid and at times reclining or supine pose in these representations. In addition, her demeanor implies both emotional and physical depletion, and there is both a pronounced abandonment of the physical and a collapsing effect, as if all mental faculties are withdrawing inward. Each chapter is dedicated to examining one of these distinct but interrelated types of femininity that flourished throughout British and American art from c. 1850 to c. 1910. The chapters for this dissertation are organized sequentially to demonstrate a selected progression of various states of consciousness, from the most obvious (the sleeping woman) to iii the more nuanced (the female Aesthete and the female medium). In each chapter, there is the visual perception of the Victorian woman as having access to otherworldly conditions of one form or another. -

Remembering the Veteran Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915

REMEMBERING THE VETERAN DISABILITY, TRAUMA, AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1915 Erin R. Corrales-Diaz A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Ross Barrett Bernard L. Herman John P. Bowles John Kasson Eleanor Jones Harvey © 2016 Erin R. Corrales-Diaz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erin R. Corrales-Diaz: Remembering the Veteran: Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915 (Under the direction of Ross Barrett) My dissertation, “Remembering the Veteran: Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915,” explores the complex ways that American artists interpreted war-induced disability after the Civil War. Examining pictorial representations of disabled veterans by George Inness, Thomas Nast, William Bell, and other artists, I argue that the veteran’s broken body became a vehicle for exploring the overwhelming sense of loss that Northerners and Southerners experienced in the war's aftermath. Oscillating between aestheticized ideals and the reality of affliction, visual representations of disabled veterans uncover postwar Americans’ deep and otherwise unspoken anxieties about masculinity, identity, and nationhood. This project represents the first major effort to historicize the visual culture of war-related disability and presents a significant deviation from previous Civil War scholarship and its focus on death. In examining these understudied representations of disability and tracing out the ways that they rework and reinforce nineteenth-century constructions of the body, this project models an approach to the analysis of period imaginings of corporeal difference that might in turn shed new light on contemporary artistic responses to physical and psychological injuries resulting from warfare.