Robinson's Reputation: Six Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bookman Anthology of Verse

The Bookman Anthology Of Verse Edited by John Farrar The Bookman Anthology Of Verse Table of Contents The Bookman Anthology Of Verse..........................................................................................................................1 Edited by John Farrar.....................................................................................................................................1 Hilda Conkling...............................................................................................................................................2 Edwin Markham.............................................................................................................................................3 Milton Raison.................................................................................................................................................4 Sara Teasdale.................................................................................................................................................5 Amy Lowell...................................................................................................................................................7 George O'Neil..............................................................................................................................................10 Jeanette Marks..............................................................................................................................................11 John Dos Passos...........................................................................................................................................12 -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Spring 1992 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism Alan Filres University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Filres, Alan, "Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism" (1992). The Courier. 293. https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc/293 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AS SOC lATE S COURIER VOLUME XXVII, NUMBER 1, SPRING 1992 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXVII NUMBER ONE SPRING 1992 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism By Alan Filreis, Associate Professor ofEnglish, 3 University ofPennsylvania Adam Badeau's "The Story ofthe Merrimac and the Monitor" By Robert]. Schneller,Jr., Historian, 25 Naval Historical Center A Marcel Breuer House Project of1938-1939 By Isabelle Hyman, Professor ofFine Arts, 55 New York University Traveler to Arcadia: Margaret Bourke-White in Italy, 1943-1944 By Randall I. Bond, Art Librarian, 85 Syracuse University Library The Punctator's World: A Discursion (Part Seven) By Gwen G. Robinson, Editor, Syracuse University 111 Library Associates Courier News ofthe Syracuse University Library and the Library Associates 159 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism BY ALAN FILREIS Author's note: In writing the bookfrom which thefollowing essay is ab stracted, I need have gone no further than the George Arents Research Li brary. -

The Poets 77 the Artists 84 Foreword

Poetry . in Crystal Interpretations in crystal of thirty-one new poems by contemporary American poets POETRY IN CRYSTAL BY STEUBEN GLASS FIRST EDITION ©Steuben Glass, A Division of Corning Glass Works, 1963 Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 63-12592 Printed by The Spiral Press, New York, with plates by The Meriden Gravure Company. Contents FOREWORD by Cecil Hemley 7 THE NATURE OF THE C OLLECTIO N by John Monteith Gates 9 Harvest Morning CONRAD A IK EN 12 This Season SARA VAN ALSTYNE ALLEN 14 The Maker W. 1-1 . AU DEN 16 The Dragon Fly LO U I SE BOGAN 18 A Maze WITTER BYNNER 20 To Build a Fire MELV ILL E CANE 22 Strong as Death GUSTAV DAVID SON 24· Horn of Flowers T H 0 M A S H 0 R N S B Y F E R R I L 26 Threnos JEAN GARR I GUE 28 Off Capri HORACE GREGORY so Stories DO NA LD H ALL S2 Orpheus CEC IL HEMLEY S4 Voyage to the Island ROB ERT HILLYER 36 The Certainty JOH N HOLMES S8 Birds and Fishes R OB I NSON JEFFER S 40 The Breathing DENISE LEVERTOV 42 To a Giraffe MARIANNE MOORE 44 The Aim LOUISE TOWNSEND NICHOLL 46 Pacific Beach KENNETH REXROTH 48 The Victorians THEODORE ROETHKE 50 Aria DELMORE SCHWARTZ 52 Tornado Warning KARL SHAPIRO 54 Partial Eclipse W. D. SNODGRASS 56 Who Hath Seen the Wind? A. M. SULLIVAN 58 Trip HOLLIS SUMMERS 60 Models of the Universe MAY SWENSON 62 Standstill JOSEPH TUSIANI 64 April Burial MARK VAN DOREN 66 Telos JOHN HALL WHEELOCK 68 Leaving RICHARD WILBUR 70 Bird Song WILL I AM CARL 0 S WILL I AMS 72 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES The Poets 77 The Artists 84 Foreword CECIL HEMLEY President, 'The Poetry Society of America, 19 61-19 6 2 Rojects such as Poetry in Crystal have great significance; not only do they promote collaboration between the arts, but they help to restore the artist to the culture to which he belongs. -

30 American Poems This Is a Sequel of Sorts to 37 American Poems, One of My First Solos

Picture here 30 American Poems This is a sequel of sorts to 37 American Poems, one of my first solos. Concentration here is on late 19th to early 20th Century works by US poets. (Summary by Bellona Times) Read by Bellona Times; total running time: 01:14:49. Dedicated Proof-Listener: April Gonzales. Meta-Coordinator & Cataloging: TriciaG. 01 - An Encounter by Robert Frost – 00:01:51 02 - Barter by Sara Teasdale – 00:01:21 03 - The Beggar Family by Morris Rosenfeld – 00:03:36 04 - California City Landscape by Carl Sandburg – 00:01:58 05 - A Chorus Girl by Edward E Cummings – 00:03:02 06 - Dinner in a Quick Lunch Room by Stephen Vincent Benet – 00:01:22 07 - The Eagle that is forgotten by Nicholas Vachel 3 Lindsay – 00:02:17 08 - A Faun in Wall Street by John Myers O'Hara – 00:01:21 09 - From a 0 Car-Window by Ruth Guthrie Harding – 00:01:10 10 - The Glory of the Day Was In Her Face by Poems American James Weldon Johnson – 00:01:05 11 - Heliodora by H.D. – 00:04:45 12 - In Time of War - Medical Unit by Edgar Lee Masters – 00:02:41 13 - Keep My Hand by Louise Driscoll – 00:00:49 14 - The Moods by Fannie Stearns Davis – 00:02:05 15 - The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes – 00:01:02 16 - Night Piece by John Dos Passos – 00:02:26 17 - Patience by American Poems American Amy Lowell – 00:01:41 18 - A Portrait of a Lady by T. -

Cummings Centennials (1914-1915)

Cummings Centennials (1914-1915) Michael Webster The school year 1914-1915 was Cummings’ senior year at Harvard, the year he moved the few blocks from 104 Irving Street to Thayer Hall in Har- vard Yard. (In the fall of 1915, Cummings continued his education at Har- vard, studying for his M.A.) Other residents of Thayer Hall included S. Foster Damon, John Dos Passos, and Robert Hillyer. According to Charles Norman, Cummings “adorned his mantelpiece with four or five elephants and his walls with ‘Krazy Kat’ comic strips” (34). In his junior and senior years, Cummings’ studies shifted from a con- centration on Latin and Greek to courses in English and Comparative Liter- ature. Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno reports that though Cummings started out as a Classics major, he eventually graduated with an “AB in Literature with concentrations in Greek and English” (59). Among the courses Cum- mings took was the year-long Literary History of England and Its Relations to that of the Continent, which covered European literature up to the Re- naissance. He also continued his Greek studies with Greek VI, which stud- ied Greek drama, and he studied Chaucer with William A. Neilson.1 In ad- dition, Cummings took George Lyman Kittredge’s course that studied in- tensively six Shakespeare plays. Kennedy writes: “most student recollec- tions depict [Kittredge] in the classroom as playing a well-rehearsed role of omniscient scholar: an imperious eagle-eyed old man hurling penetrating questions or answering queries with authoritative scorn as he lifted his well -trimmed white beard in the air” (Dreams 63). -

Tul¢W Heim, Instruc

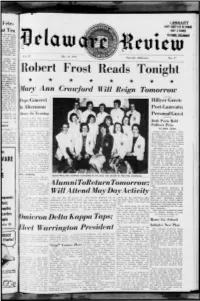

Fete .JIHRARY r'C RSITY Of OElAWAJi t Tea MAY 181959 Venture Po . will be feted + N£WARK, DEtAWAM a tea spon. h department ich awards the winn rs ual co~t e t. he tea and ntation Will tUl¢W heim, instruc. faculty ad. \ ·ul. 82 ~fa , · 15, 1959 se nior, wiLt Newark, Delaware No. 27 A cademy . f The [d Poetry Award Harold Bruce his "Flori d~ ritten in La • Robert Frost Reads Tonight * * * * * * * Crawford Will Reign /Tomorrow* Pops Concert Hillyer Greets In Afternoon Poet-Laureate; magazine w s Dan ce In Evening Personal Guest d m ay be ob · n desk In the TomoiTOI\··s .\J ay D y fc tivi - 1 ., tie ril l begin 1\iLh th crown Both Poets Hold .. liP IJ[ 1he q uePn of i hi year's Ji ~Y Court. :\Jary .-\nn Crawford, at 2:30 on the \ \.•)me n'" hockey Pulitzer Prize Page 1) field . By MIKE LEWIS Fod 11·i :1g th e f''lronatir)J1 , rec R obert Frost, America's Poet . ··Typ" .Ylorris 1 oani;ion \\'i ll be g iven to the Laureate, will visit the univers . icki Dono\·a n, dlfferrnt m m'hcr · of the May ity campus tonight f or a read.. t iona! A ctinn ; 11om the fou r classes. Cnurt ing in Mitchell Hall, at 8 p. m. junior, Ed. fre. hmnn . oph0mor . junior. Frost, :ponsored by the English ra J Action; and ;:rnior. I n he nior cl a.:>s, Department, is a personal g uest sophomore, Jan e Prr<:on s \\' a~ elect ed maid of Dr. -

American Literature

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology American Literature Subject: AMERICAN LITERATURE Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Contexts of American Literature The Puritan Context, The Consolidation and Dispersal of the Puritan Utopia, The Puritans as Literary Artists, Some “Other” Contexts of American Literature, Form the Colonial to the Federal: The Contexts of the American Enlightenment American Fiction Background, Reading the Text, Characterization, Narrative technique and Structure, Critical Perspective, Background to Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huckleberry Finn and its Narrative, Themes and Characterization in Huckleberry Finn, Language in Huckleberry Finn, Humour and Other Issues in Huckleberry Finn American Prose Revolutionary Prose in America, American prose in the Period of National Consolidation, The „Other‟ Side of American Romanticism, American Prose Around the Civil War, American Prose in the Post-Civil War Period, American Poetry Background, The Text 1: Walt Whitman, The Text 2: Emily Dickinson, Structure and Style, Critical Perspective, Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams Ezra Pound, Adrienne Rich American Short Story The American Short Story, Hemingway: A Clean, Well- Lighted Place, William Faulkner: The Bear, Comparisons and Contrasts Suggested Readings: 1. English and American Literature: John Cotton Dana 2. The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger 3. American Literature : Willam E Cain CONTENTS Chapter1 : American Literature Chapter 2 : Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Chapter 3 : Moby-Dick Chapter 4 : Walt Whitman Chapter 5 : Emily Dickinson Chapter 6 : Robert Frost Chapter 7 : Wallace Stevens Chapter 8 : William Carlos Williams Chapter 9 : Ezra Pound Chapter 10 : Adrienne Rich Chapter 11 : A Clean, Well-Lighted Place Chapter - 1 American Literature American literature is the written or literature produced in the area of the United States and its preceding colonies. -

School Lists Recor the Recordings

DOCUMENT RESUME TE 000 767 ED 022 775 By- Schreiber. Morris, Ed. FOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SECONDARY AN ANNOTATED LIST OFRECORDINGS IN TIC LANGUAGE ARTS SCHOOL COLLEGE National Council of Teachers ofEnglish. Charripaign. IN. Pub Date 64 Note 94p. Available from-National Cound ofTeachers of English. 508 South SixthStreet, Champaign. Illinois 61820 (Stock No. 47906. HC S1.75). EDRS Price MF-S0.50 HC Not Availablefrom MRS. ENGLISH 1)=Ators-Ati:RICAN LITERATURE. AUDIOVISUALAIDS. DRAMA. *ENGLISH INSTRUCTION. TURE FABLES. FICTION. *LANGUAGEARTS. LEGENDS. *LITERATURE.*PHONOGRAPH RECORDS. POETRY. PROSE. SPEECHES The approximately 500 recordings inthis selective annotated list areclassified by sublect matter and educationallevel. A section for elementaryschool lists recor of poetry. folksongs, fairytales. well-known ch4dren's storiesfrom American and w literature, and selections from Americanhistory and social studies.The recordings for both secondary school and collegeinclude American and English prose.poetry. and drama: documentaries: lectures: andspeeches. Availability Information isprovided, and prices (when known) are given.(JS) t . For Elementary School For Secoidary 'School For Colle a a- \ X \ AN ANNOTATED LIST 0 F IN THE LANGUAGE ARTS NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERSOF tNGLISH U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WILIAM I OFFICE Of EDUCATION TINS DOCUMENT HAS 1EEN REPIODUCED EXACTLY AS DECEIVED FION THE PERSON 01 016ANI1ATION 0116INATNI6 IT.POINTS OF VIEW 01 OPINIONS 1 STATED DO NOT NECESSAINLY REPIESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION 01 POLICY. i AN ANNOTATED LIST OF RECORDINGS IN I THE LANGUAGE ARTS I For 3 Elementhry School Secondary School College 0 o Compiled and Edited bY g MORRIS SCHREIBER D Prepared for the NCI% by the Committee on an Annotated Recording List a Morris Schreiber Chairman Elizabeth O'Daly u Associate Chairman AnitaDore David Ellison o Blanche Schwartz o NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERS OF ENGLISH u Champaign, Illinois i d NCTE Committee on Publications James R. -

Name Contest Name Area Year Amount Title Volume# Judges

NAME CONTEST NAME AREA YEAR AMOUNT TITLE VOLUME# JUDGES Fortune, Helen Hopwood Major Drama 1931 $1,000 "Dark Glass: A Drama in Four Acts and Judgment Day: 4 Thomas H. Dickinson, Paul (includes A Play in One Act" Osborn, D. L. Quirk Hopkins, Vivian Hopwood Major Drama 1931 $1,000 "A Courtier of Elizabeth: A One Act Play and One Loyal 8 Thomas H. Dickinson, Paul Subject: A Three Act Play" Osborn, D. L. Quirk, Thomas Humphreys, Richard Hopwood Major Drama 1931 $250 "The Blue Anchor" 9 Thomas W. Stevens (?); Thomas H. Dickinson, Paul Smith, Elizabeth W. Hopwood Major Drama 1931 $1,000 "Francine Nolan" (manuscript missing) 11 Thomas W. Stevens (?); Thomas H. Dickinson, Paul Boillotat, Dorothy Hopwood Major Essay 1931 $1,500 "Mosaic" 1 Henry Seidel Canby, Robert (later Donnelly) Morss Lovett, Agnes Repplier Gorman, William J. Hopwood Major Essay 1931 $1,500 "Essays" (manuscript missing) 7 Henry Seidel Canby, Robert Morss Lovett, Agnes Repplier Chambers, Lorna D. Hopwood Major Fiction 1931 $1,000 "The Mad Stone" (manuscript missing) 3 James Boyd, John Towner Frederick, Ellen Glasgow Fortune, Helen Hopwood Major Fiction (Novel and 1931 see above "This Man Making: A Novel and The Taffy Pup: A Short 5 James Boyd, John Towner Short Story) Story" Frederick, Ellen Glasgow Gilman, Jean A. Hopwood Major Fiction (Novel) 1931 $1,000 "Poignant Star" 6 James Boyd, John Towner Frederick, Ellen Glasgow Bonner, Sue Grundy Hopwood Major Poetry 1931 $1,500 "Fantasy in Crystal" 2 Stephen Vincent Benet, Witter Bynner, Louis Untermeyer Jennings, Frances Hopwood Major Poetry 1931 $1,000 "The Heavenly Pagan" (manuscript missing) 10 Stephen Vincent Benet, Witter Bynner, Louis Untermeyer Humphreys, Richard Hopwood Minor Drama 1931 $250 "The Well: A One-Act Play" 13 Thomas H. -

Karl Shapiro and Poetry, a Magazine of Verse (1950-1955)

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/147068 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-10 and may be subject to change. Karl Shapiro and Poetry, A Magazine of Verse (1950-1955) • SRsjgy 'Ê \ Diederik Oostdijk Karl Shapiro and Poetry: A Magazine of Verse (1950-1955) Karl Shapiro and Poetry: Λ Magazine of Verse (1950-1955) een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Letteren Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen, volgens besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 14 september 2000 des namiddags om 1.30 uur precies door Diederik Michiel Oostdijk geboren op 12 februari 1972 te Tilburg Promotor: Prof dr. G.A.M. Janssens Co-promotor: Mw. dr. M.L.M. Janssen Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. J.Th.J. Bak Prof. dr. G.C.A.M. van Gemert Prof. dr. R.J. Lyall (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) to my mother & the memory of my father Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Archival Materials xi Preface xm Chapter 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Poetry and Periodical Publishing before 1950 1 1.2 Poetry before Shapiro 9 1.3 Shapiro before Poetry 17 Chapter 2. Poetry (1950-1951) 27 2.1 Karl Shapiro and the Board of Trustees 27 2.2 The Poetry Section 34 2.3 The Prose Section 51 2.4 Special Issues 63 Chapter 3. -

The Literary Criticism of Randall Jarrell

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy.