Gun Running in Papua New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complaint

Case 2:15-cv-05805-R-PJW Document 1 Filed 07/31/15 Page 1 of 66 Page ID #:1 1 C.D. Michel – Calif. S.B.N. 144258 Joshua Robert Dale – Calif. S.B.N. 209942 2 MICHEL & ASSOCIATES, P.C. 180 E. Ocean Blvd., Suite 200 3 Long Beach, CA 90802 Telephone: (562) 216-4444 4 Facsimile: (562) 216-4445 [email protected] 5 [email protected] 6 Attorneys for Plaintiff Wayne William Wright 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 WESTERN DIVISION - COURTHOUSE TBD 11 WAYNE WILLIAM WRIGHT, ) CASE NO. __________________ ) 12 Plaintiff, ) COMPLAINT FOR: ) 13 v. ) (1) VIOLATION OF FEDERAL ) CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER 14 CHARLES L. BECK; MICHAEL N. ) COLOR OF LAW FEUER; WILLIAM J. BRATTON; ) (42 U.S.C. §1983) 15 HEATHER AUBRY; RICHARD ) TOMPKINS; JAMES EDWARDS; ) (a) VIOLATION OF 16 CITY OF LOS ANGELES; and ) FOURTH DOES 1 through 50, ) AMENDMENT; 17 ) Defendants. ) (b) VIOLATION OF FIFTH 18 ) AMENDMENT; 19 (c) VIOLATION OF FOURTEENTH 20 AMENDMENT; 21 (2) STATE LAW TORTS OF CONVERSION & TRESPASS 22 TO CHATTELS; AND 23 (3) VIOLATION OF RACKETEER INFLUENCED AND 24 CORRUPT ORGANIZATIONS ACT 25 (18 U.S.C. §1961, et seq.) 26 (4) CONSPIRACY TO VIOLATE RACKETEER INFLUENCED 27 AND CORRUPT ORGANIZATIONS ACT 28 (18 U.S.C. §1962(d)) DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Case 2:15-cv-05805-R-PJW Document 1 Filed 07/31/15 Page 2 of 66 Page ID #:2 1 JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2 1. Jurisdiction of this action is founded on 28 U.S.C. -

Ultimax Layout

THE LIGHTEST 5.56mm Calibre Machine Gun in the World The ultimate 5.56mm light machine gun... the lightest squad automatic weapon in the world that meets all modern combat requirements. Designed from the onset for one-man operation, the Ultimax 100 is a gas- operated magazine fed weapon. The Ultimax 100 incorporates a number of significantly outstanding features: PATENTED “CONSTANT RECOIL” PRINCIPLE LIGHTWEIGHT A revolutionary “Constant Recoil” concept practically The Ultimax 100, when fully loaded with 100 rounds of eliminates recoil and gives the Ultimax 100 exceptional ammunition, weighs only 6.8kg, lighter than many other controllability in automatic fire, better than any existing 5.56mm LMG empty. assault rifle and machine guns. FIREPOWER ACCURATE AND CONTROLLABLE The combination of lightweight and accuracy leads to The minimal recoil of the Ultimax 100 enables it to a dramatic increase in effective firepower. A saving of be fired accurately in full automation from the ammunition comes with accuracy and the lightness of hip, or with one arm. The controllability of the the weapon also enables the soldier to carry more Ultimax 100 is also unaffected even when fired ammunition. with the butt detached, a feature especially useful when space is limited or confined such QUICK RELEASE BARREL The Ultimax 100 comes with a quick-change barrel as in airborne or armoured infantry roles. feature. The barrels are pre-zeroed and can be changed quickly by the soldier. RELIABLE A 3-position gas regulator enables the weapon to function reliably even in adverse environment such as jungle, sub-zero and desert conditions. -

NZCCC TURANGI AGM AUCTION, Saturday 10 March, 2018 Turangi Holiday Park, Turangi

NZCCC TURANGI AGM AUCTION, Saturday 10 March, 2018 Turangi Holiday Park, Turangi The following items will be offered for sale on behalf of the vendors following the AGM at the Turangi Meeting. The AGM starts at 1pm. 1. The NZCCC accepts no responsibility for any incorrect description of any lot. Viewing opportunity will precede the auction. Any vendor reserve is indicated by the $ amount at the end of each lot description. 2. Bids, starting at $5, will be accepted only from currently financial members or their approved guests and the Auctioneer’s decision will be final. 3. An NZCCC vendor commission rate of 10% (minimum $1) will apply to each lot offered for sale. No commission applies to buyers. 4. All lots sold will be delivered to the purchaser or postal bid coordinator as appropriate at the time of sale. 5. A full accounting of sales will be recorded and a list of auction results will be published with the AGM report. 6. Overseas bidders must make private arrangements for the delivery of ammunition. Postal Bids: Please ensure that postal (absentee) bids are in the Editor’s hands by Monday March 5. Post to Kevan Walsh 4 Milton Road, Northcote Point, or email [email protected] . A scan of the postal bid form would be good, but simply emailing the editor with your bids will also be fine. For postal bids a payment of $5 is required. Either make a bank deposit ( BNZ account 02-0214-0052076-00) and let the Treasurer Terry Castle know, or post your bids with a cheque or cash to Kevan. -

501 Cmr: Executive Office of Public Safety

501 CMR: EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF PUBLIC SAFETY 501 CMR 7.00: APPROVED WEAPON ROSTERS Section 7.01: Purpose 7.02: Definitions 7.03: Development of Approved Firearms Roster 7.04: Criteria for Placement on Approved Firearms Roster 7.05: Compliance with the Approved Roster by Licensees 7.06: Appeals for Inclusion on or Removal from the Approved Firearms Roster 7.07: Form and Publication of the Approved Firearms Roster 7.08: Development of a Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.09: Criteria for Placement on Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.10: Large Capacity Weapons Not Listed 7.11: Form and Publication of the Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.12: Development of the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.13: Criteria for Placement on the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.14: Appeals for Inclusion on the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.15: Form and Publication of the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.16: Severability 7.01: Purpose The purpose of 501 CMR 7.00 is to provide rules and regulations governing the inclusion of firearms, rifles and shotguns on rosters of weapons referred to in M.G.L. c. 140, §§ 123 and 131¾. 7.02: Definitions As used in 501 CMR 7.00: Approved Firearm means a firearm make and model that passed the testing requirements of M.G.L. c. 140, § 123 and was subsequently approved by the Secretary. Included are those firearms listed on the current Approved Firearms Roster and those firearms approved by the Secretary of Public Safety that will be included on the next published Approved Firearms Roster. -

Case 1:14-Cv-01211-JAM-SAB Document 24 Filed 01/09/15 Page

Case 1:14-cv-01211-JAM-SAB Document 24 Filed 01/09/15 Page 1 of 6 Case 1:14-cv-01211-JAM-SAB Document 24 Filed 01/09/15 Page 2 of 6 Case 1:14-cv-01211-JAM-SAB Document 24 Filed 01/09/15 Page 3 of 6 ADMINISTRATIVE RECORD Page Date Description Correspondence and Litigation 1-6 July 2013 Legal Memo submitted with EP Arms submission (Davis & Associates) 7-9 February 2014 Classification Letter (Davis & Associates) 10-19 March 2014 Legal Memo submitted with EP Arms Request for Reconsideration (Davis & Associates) 20-25 Reconsideration Classification Letter (Davis & Associates) 26-33 March 2010 Classification Letter (Quentin Laser) 34-36 November 2013 Classification Letter (Bradley Reece) 37-42 May 2013 Classification Letter (Kenney Enterprises) 43-50 Portion of chapter in The AR-15/M-16 Practical Guide dealing with making an AR- type firearm 51-56 Graphic representation of the firing cycle of an AR-type firearm Semi Auto Functioning of an AR-15) AR-15 (Folder) 57-59 May 2014 Classification Letter (ERTW Consulting) 60-61 May 1983 Classification Letter (SGW) 62 May 1992 Classification Letter (Philadelphia Ordnance) 63-64 July 1994 Classification Letter (Thomas Miller) 65-66 December 2002 Classification Letter (Mega Machine Shop) 67 July 2003 Classification Letter (Justin Halford) 68-69 January 2004 Classification Letter (Continental Machine Tool) 70-71 March 2004 Classification Letter (Randy Paschal) 72-73 January 2004 Classification Letter (Continental Machine Tool) 74-77 July 2006 Classification Letter (Kevin Audibert) 78-79 April 2006 Classification -

Vance Outdoors Price List Eff 08/13/20

3723 CLEVELAND AVENUE, COLUMBUS, OHIO 43224 PHONE 614-471-0712 / FAX 614-471-2134 / [email protected] WWW.VANCESLE.COM STATE OF OHIO CONTRACT #RS900319 / INDEX #GDC004 FIREARMS, AMMUNITION, LESS LETHAL MUNITIONS AND RELATED LAW ENFORCEMENT MATERIALS AND SUPPLIES 2020 PRICE LIST VANCE OUTDOORS, INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTRACT #RS900319 / INDEX #GDC004 PAGE TITLE 3 ASP Batons, Restraints, Lights, Training & OC Price List 23 Defense Technology Less Lethal Munitions Price List 41 Fox Labs Law Enforcement Aerosol Projectors Price List 43 Hatch Less Lethal Munitions Bag & Protective Gear Price List 52 Hornady Law Enforcement Ammunition Price List 55 Monadnock Batons, Restraints & Riot Control Price List 77 Nightstick Fire and Law Enforcement Flashlights Price List 87 Rings Manufacturing Non-Lethal Training Guns Price List 102 Sabre Law Enforcement Aerosol Projectors Price List 111 Safariland Duty Gear Price List 121 Simunition Training Cartridges, Kits & Equipment Price List 131 Smith & Wesson Restraints, Firearms and Suppressors Price List 137 Streamlight Law Enforcement Flashlights Price List 146 Winchester Law Enforcement Ammunition Price List 2020 ASP BATONS, RESTRAINTS, LIGHTS & OC VANCE OUTDOORS, INC. RS900319 / GDC004 Product Discount % Up Description UOM 1 to 10 Units 11 to 49 Units 50 to 99 Units 100 + Units Retail Number To: BATONS 16/40 BATONS Friction 52212 F16AF Airweight, Foam Each $90.00 $82.75 $78.25 $77.00 $127.87 39.8% 52211 F16BF Black Chrome, Foam Each $90.00 $82.75 $78.25 $77.00 $127.87 39.8% 52213 F16EF Electroless, Foam -

JULY/AUGUST 1986 Vol

11 Safari~Lamina~ Process.TM Experience Innovation with purpose. t .-;;:::::::::=================~ .... • Tough Customers Dillon Precision has sold over 50,000 pro gressive reloaders, most of them to average shooters and darn nice guys. Some of our cus tom~rs . however are pretty damn tough. We cant give you all the details but we can tell you this. Dillon progressive reloaders are in use by members of the U.S. Special Forces the U.S. Seal Team in Norfolk, VA, the 1s'. RAELI MILITARY INDUSTRIES and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Agents from the U.S. Secret Service stuff Dillon loaded 9 mm's into their UZl 's. Swat teams around the world prepare their special ammunition on Dillon re loaders. Governments in Thailand, Equador and the Philippines protect their leaders with Dillon ammo. Rumor has it that Dillon loaded ammunition went ashore in Grenada Hell even Rambo's blanks were loaded on a .Dillon '. Wherev_er there is need for special purpose ammunition that absolutely must not fail - Dil lon is there . • The New Dillon RL550 Based on the RL450, the best selling pro gressive reloader in history, the new RL550 fills the demands of the worlds toughest cus tomers. The new automatic powder and primer systems, combined with interchangeable die holding tool heads, make the Dillon RL550 incredibly simple for a beginner, as well as quickly producing match grade ammo for the professional. The Dillon RL550 is available in over 115 different rifle and pistol calibers. Priced at $234.95, the Dillon RL550 is com plete to load one caliber, less dies. -

California State Laws

State Laws and Published Ordinances - California Current through all 372 Chapters of the 2020 Regular Session. Attorney General's Office Los Angeles Field Division California Department of Justice 550 North Brand Blvd, Suite 800 Attention: Public Inquiry Unit Glendale, CA 91203 Post Office Box 944255 Voice: (818) 265-2500 Sacramento, CA 94244-2550 https://www.atf.gov/los-angeles- Voice: (916) 210-6276 field-division https://oag.ca.gov/ San Francisco Field Division 5601 Arnold Road, Suite 400 Dublin, CA 94568 Voice: (925) 557-2800 https://www.atf.gov/san-francisco- field-division Table of Contents California Penal Code Part 1 – Of Crimes and Punishments Title 15 – Miscellaneous Crimes Chapter 1 – Schools Section 626.9. Possession of firearm in school zone or on grounds of public or private university or college; Exceptions. Section 626.91. Possession of ammunition on school grounds. Section 626.92. Application of Section 626.9. Part 6 – Control of Deadly Weapons Title 1 – Preliminary Provisions Division 2 – Definitions Section 16100. ".50 BMG cartridge". Section 16110. ".50 BMG rifle". Section 16150. "Ammunition". [Effective until July 1, 2020; Repealed effective July 1, 2020] Section 16150. “Ammunition”. [Operative July 1, 2020] Section 16151. “Ammunition vendor”. Section 16170. "Antique firearm". Section 16180. "Antique rifle". Section 16190. "Application to purchase". Section 16200. "Assault weapon". Section 16300. "Bona fide evidence of identity"; "Bona fide evidence of majority and identity'. Section 16330. "Cane gun". Section 16350. "Capacity to accept more than 10 rounds". Section 16400. “Clear evidence of the person’s identity and age” Section 16410. “Consultant-evaluator” Section 16430. "Deadly weapon". Section 16440. -

“BULLET BUTTON” / “ASSAULT WEAPON” Quick Reference Guide

“BULLET BUTTON” / “ASSAULT WEAPON” quick Reference Guide PREREQUISITE FEATURES or telescoping stock, (D) A grenade launcher or the weapon without burning the bearer’s hand, QUICK TIPS OF AN ASSAULT WEAPON (AW) flare launcher, (E) A flash suppressor, or (F) A except a slide that encloses the barrel; (J) The FOR GUN OWNERS WITH The Penal Code now classifies the following as forward pistol grip. capacity to accept a detachable magazine at FIREARMS NOW an AW: PISTOLS: A semiautomatic pistol that does not some location outside of the pistol grip. have a fixed magazine but has anyone of the SHOTGUNS: While the change in the Penal CLASSIFIED AS RIFLES: A semiautomatic, centerfire rifle that following: (G) A threaded barrel, capable of ac- Code affects certain rifles and pistols, the DOJ does not have a fixed magazine but has any “ASSAULT WEAPONS” cepting a flash suppressor, forward handgrip, has taken the position that semiautomatic shot- one of the following: (A) A pistol grip that pro- or silencer; (H) A second handgrip; (I) A shroud guns required to be equipped with “bullet but- On January 1, 2017, the definition trudes conspicuously beneath the action of the that is attached to, or partially or completely en- tons” are also affected. of an “assault weapon” (“AW”) under weapon, (B) A thumbhole stock, (C) A folding California law was changed to include circles, the barrel that allows the bearer to fire firearms which were required to be equipped with a “bullet button” or similar KEY DEFINITIONS magazine locking device. This change does not affect ex- “FIXED MAGAZINE”- An ammunition feeding device contained in, or permanently attached to, a firearm in such a manner that the device cannot isting definitions of other types of AWs, be removed without disassembly of the firearm action. -

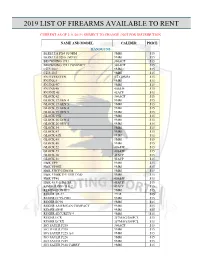

2019 List of Firearms Available to Rent

2019 LIST OF FIREARMS AVAILABLE TO RENT CURRENT AS OF 2/11/2019 | SUBJECT TO CHANGE | NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS BERETTA PX4 STORM 9MM $15 BERETTA 92FS | M9A1 9MM $15 BROWNING 1911 380ACP $15 BROWNING 1911 COMPACT 380ACP $15 CZ P-10 C 9MM $15 CZ P-10 F 9MM $15 FN FIVESEVEN 5.7X28MM $15 FN FNS-9 9MM $15 FN FNS-9C 9MM $15 FN FNS-40 40S&W $15 FN FNX-45 45ACP $15 GLOCK 42 380ACP $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19X 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 34 9MM $15 GLOCK 43 9MM $15 GLOCK 43X 9MM $15 GLOCK 45 9MM $15 GLOCK 48 9MM $15 GLOCK 22 40S&W $15 GLOCK 23 40S&W $15 GLOCK 36 45ACP $15 GLOCK 21 45ACP $15 H&K VP9 9MM $15 H&K VP9SK 9MM $15 H&K P30 V-3 DA/SA 9MM $15 H&K P30SK V-1 LEM DAO 9MM $15 H&K VP40 40S&W $15 H&K 45 V-1 DA/SA 45ACP $15 KIMBER PRO TLE 2 45ACP $15 REMINGTON RP9 9MM $15 RUGER SR-22 22LR $15 RUGER LC9S-PRO 9MM $15 RUGER EC9S 9MM $15 RUGER AMERICAN COMPACT 9MM $15 RUGER SR9E 9MM $15 RUGER SECURITY-9 9MM $15 RUGER LCR 357MAG/38SPCL $15 RUGER LCRX 357MAG/38SPCL $15 SIG SAUER P238 380ACP $15 SIG SUAER P938 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P225 A-1 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P226 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P229 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P320 CARRY 9MM $15 NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS SIG SAUER P320–M17 9MM 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P365 9MM $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P22 COMPACT 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON REVOLVER 617 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON BODYGUARD 380 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P380 SHIELD EZ 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P9 M2.0 5” FDE 9MM $15 SMITH & -

Information Bulletin 2014-BOF-01 New and Amended Firearms/Weapons Laws Page 2

Kamala D. Harris, Attorney General California Department of Justice DIVISION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT Larry J. Wallace, Director Subject: No: 2014-BOF-01 New and Amended Firearms/Weapons Laws Date: Bureau of Firearms January 10,2014 TO: All California Criminal Justice and Law Enforcement Agencies, Centralized List of Firearms Dealers, Manufacturers, and Exempted Federal Firearms Licensees This bulletin provides a brief summary of new and amended California firearms/weapons laws that take effect January 1, 2014, unless otherwise noted. You may access the full text of the bills via the Internet at http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/. AB 809 (Stats. 2011, ch. 745)- Collection and Retention of Long Gun Information • Commencing January 1, 2014, requires information regarding the sale or transfer oflong guns (rifles and shotguns) to be reported, collected, and retained in the same manner as handguns. (Pen. Code,§§ 11106, 26905.) AB 1559 (Stats. 2012, ch. 691) -Fees • Commencing January 1, 2014, only one processing fee will be charged for a single transaction (e.g. sale, transfer, miscellaneous reports of ownership, etc.) regardless ofthe number offirearms. (Pen. Code,§ 28240.) AB 48 (Stats. 2013, ch. 728)- Large-Capacity Magazines • With specified exceptions, makes it a misdemeanor to knowingly manufacture, import, keep for sale, offer or expose for sale, or give, lend, buy, or receive any large-capacity magazine conversion kit that is capable of converting an ammunition feeding device into a large-capacity magazine. (Pen. Code, § 32311.) • With specified exceptions, makes it either a misdemeanor or a felony to buy or receive a large capacity magazine. (Pen. Code, § 3231 0.) AB 170 (Stats. -

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law April 2016 Contents 1. An overview – frequently asked questions on firearms licensing .......................................... 3 2. Definition and classification of firearms and ammunition ...................................................... 6 3. Prohibited weapons and ammunition .................................................................................. 17 4. Expanding ammunition ........................................................................................................ 27 5. Restrictions on the possession, handling and distribution of firearms and ammunition .... 29 6. Exemptions from the requirement to hold a certificate ....................................................... 36 7. Young persons ..................................................................................................................... 47 8. Antique firearms ................................................................................................................... 53 9. Historic handguns ................................................................................................................ 56 10. Firearm certificate procedure ............................................................................................... 69 11. Shotgun certificate procedure ............................................................................................. 84 12. Assessing suitability ............................................................................................................