Ernest Renan, “What Is a Nation?”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touring a Unified Italy, Part 2 by John F

Browsing the Web: Touring A Unified Italy, Part 2 by John F. Dunn We left off last month on our tour of Italy—commemo- rating the 150th Anniversary of the Unification of the na- tion—with a relaxing stop on the island of Sardinia. This “Browsing the Web” was in- spired by the re- lease by Italy of two souvenir sheets to celebrate the Unifi- cation. Since then, on June 2, Italy released eight more souvenir sheets de- picting patriots of the Unification as well as a joint issue with San Marino (pictured here, the Italian issue) honoring Giuseppe and Anita Garibaldi, Anita being the Brazilian wife and comrade in arms of the Italian lead- er. The sheet also commemorates the 150th Anniversary of the granting of San Marino citizen- ship to Giuseppe Garibaldi. As we continue heading south, I reproduce again the map from Part 1 of this article. (Should you want Issue 7 - July 1, 2011 - StampNewsOnline.net 10 to refresh your memory, you can go to the Stamp News Online home page and select the Index by Subject in the upper right to access all previous Stamp News Online ar- ticles, including Unified Italy Part 1. So…moving right along (and still in the north), we next come to Parma, which also is one of the Italian States that issued its own pre-Unification era stamps. Modena Modena was founded in the 3rd century B.C. by the Celts and later, as part of the Roman Empire and became an important agricultural center. After the barbarian inva- sions, the town resumed its commercial activities and, in the 9th century, built its first circle of walls, which continued throughout the Middle Ages, until they were demolished in the 19th century. -

Albert Schweitzer: a Man Between Two Cultures

, .' UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY ALBERT SCHWEITZER: A MAN BETWEEN TWO CULTURES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES OF • EUROPE AND THE AMERICAS (GERMAN) MAY 2007 By Marie-Therese, Lawen Thesis Committee: Niklaus Schweizer Maryann Overstreet David Stampe We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Languages and Literatures of Europe and the Americas (German). THESIS COMMITIEE --~ \ Ii \ n\.llm~~~il\I~lmll:i~~~10 004226205 ~. , L U::;~F H~' _'\ CB5 .H3 II no. 3Y 35 -- ,. Copyright 2007 by Marie-Therese Lawen 1II "..-. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS T I would like to express my deepest gratitude to a great number of people, without whose assistance, advice, and friendship this thesis w0l!'d not have been completed: Prof. Niklaus Schweizer has been an invaluable mentor and his constant support have contributed to the completion of this work; Prof. Maryann Overstreet made important suggestions about the form of the text and gave constructive criticism; Prof. David Stampe read the manuscript at different stages of its development and provided corrective feedback. 'My sincere gratitude to Prof. Jean-Paul Sorg for the the most interesting • conversations and the warmest welcome each time I visited him in Strasbourg. His advice and encouragement were highly appreciated. Further, I am deeply grateful for the help and advice of all who were of assistance along the way: Miriam Rappolt lent her editorial talents to finalize the text; Lynne Johnson made helpful suggestions about the chapter on Bach; John Holzman suggested beneficial clarifications. -

The Constantinian Order of Saint George and the Angeli, Farnese and Bourbon Families Which Governed It

Available at a pre-publication valid until 28th December 2018* special price of 175€ Guy Stair Sainty tienda.boe.es The Constantinian Order of Saint George and the Angeli, Farnese and Bourbon families which governed it The Boletín Oficial del Estado is pleased to announce the forthcoming publication of The Constantinian Order of Saint George and the Angeli Farnese and Bourbon families which governed it, by Guy Stair Sainty. This is the most comprehensive history of the Order from its foundation to the present, including an examination of the conversion of Constantine, the complex relationships between Balkan dynasties, and the expansion of the Order in the late 16th and 17th centuries until its acquisition by the Farnese. The passage of the Gran Mastership from the Farnese to the Bourbons and the subsequent succession within the Bourbon family is examined in detail with many hitherto unpublished documents. The book includes more than 300 images, and the Appendix some key historic texts as well as related essays. There is a detailed bibliography and index of names. The Constantinian Order of Saint George 249x318 mm • 580 full color pages • Digitally printed on Matt Coated Paper 135 g/m2 Hard cover in fabric with dust jacket SHIPPING INCLUDED Preorder now Boletín Oficial del Estado * Applicable taxes included. Price includes shipping charges to Europe and USA. Post publication price 210€ GUY STAIR SAINTY, as a reputed expert in the According to legend the Constantinian Order is the oldest field, has written extensively on the history of Orders chivalric institution, founded by Emperor Constantine the GUY STAIR SAINTY Great and governed by successive Byzantine Emperors and of Knighthood and on the legitimacy of surviving their descendants. -

Nietzsche's Orientalism

Duncan Large Nietzsche’s Orientalism Abstract: Edward Said may omit the German tradition from his ground-breaking study of Orientalism (1978), but it is clearly appropriate to describe Nietzsche as Orientalist in outlook. Without ever having left Western Europe, or even having read very widely on the subject, he indulges in a series of undiscriminating stereotypes about “Asia” and “the Orient”, borrowing from a range of contemporary sources. His is an uncom- mon Orientalism, though, for his evaluation of supposedly “Oriental” characteristics is generally positive, and they are used as a means to critique European decadence and degeneration. Because he defines the type “Oriental” reactively in opposition to the “European”, though, it is contradictory. Furthermore, on Nietzsche’s analysis “Europe” itself is less a type or a geographical designation than an agonal process of repeated self-overcoming. He reverses the received evaluation of the Europe-Orient opposition only in turn to deconstruct the opposition itself. Europe first emerged out of Asia in Ancient Greece, Nietzsche claims, and it has remained a precarious achieve- ment ever since, repeatedly liable to “re-orientalisation”. He argues that “Oriental” Christianity has held Europe in its sway for too long, but his preferred antidote is a further instance of European “re-orientalisation”, at the hands of the Jews, whose productive self-difference under a unified will he views as the best model for the “good Europeans” of the future. Keywords: Orientalism, Edward Said, Asia, Europe, Christianity, Jews, good Europeans. Zusammenfassung: Auch wenn in Edward Saids bahnbrechender Studie Orienta- lismus (1978) die deutsche Tradition nicht vorkommt, lässt sich Nietzsches Haltung doch als ‚orientalistisch‘ beschreiben. -

The Fascist Jesus: Ernest Renan's Vie De Jésus and the Theological Origins of Fascism a Dissertation Submitted to the Un

The Fascist Jesus: Ernest Renan’s Vie de Jésus and the Theological Origins of Fascism A dissertation submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Theology in Systematic and Philosophical Theology 2014 Ralph E. Lentz II UWTSD 28000845 1 Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed……Ralph E. Lentz II Date …26 January 2014 2. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of …Masters of Theology in Systematic and Philosophical Theology……………………………………………………………................. Signed …Ralph E. Lentz II Date ……26 January 2014 3. This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed candidate: …Ralph E. Lentz II Date: 26 January 2014 4. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying, inter- library loan, and for deposit in the University’s digital repository Signed (candidate)…Ralph E. Lentz II Date…26 January 2014 Supervisor’s Declaration. I am satisfied that this work is the result of the student’s own efforts. Signed: ………………………………………………………………………….. Date: ……………………………………………………………………………... 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………….4 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………5 -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and Ornament

VOLUME: 4 WINTER, 2004 Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and Ornament: Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art at the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture Review by Nancy H. Ramage 1) is a copy of a vase that belonged to Ithaca College Hamilton, painted in Wedgwood’s “encaustic” technique that imitated red-figure with red, An unusual and worthwhile exhibit on the orange, and white painted on top of the “black passion for vases in the 18th century has been basalt” body, as he called it. But here, assembled at the Bard Graduate Center in Wedgwood’s artist has taken all the figures New York City. The show, entitled that encircle the entire vessel on the original, Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and and put them on the front of the pot, just as Ornament: Selections from The Metropolitan they appear in a plate in Hamilton’s first vol- Museum of Art, was curated by a group of ume in the publication of his first collection, graduate students, together with Stefanie sold to the British Museum in 1772. On the Walker at Bard and William Rieder at the Met. original Greek pot, the last two figures on the It aims to set out the different kinds of taste — left and right goût grec, goût étrusque, goût empire — that sides were Fig. 1 Wedgwood Hydria, developed over a period of decades across painted on the Etruria Works, Staffordshire, Britain, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany. back of the ves- ca. 1780. Black basalt with “encaustic” painting. The at the Bard Graduate Center. -

2 Ernest Renan the LIFE Ofjesus (1863)6

~ ;, I ~: ~-"..;t'.'",--; .; c1;c; 2 , Ernest Renan . :" .1;;;;:,-. THE LIFE OFjESUS (1863)6 ,:;";::"]",C c ic1 ~?~";:":c"c, ,- In 1835, the same year that Baur's academic work on St. Paul appeared, another f::j'!; member of the Tiibingen school, David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874), pub- ...." lished a book that introduced the techniques of Higher Criticism to a wide gen- eral audience and earned the movement immediate renown as well as infamy, In his otherwise cautious Life of Jesus, Strauss boldly dismissed all of the supernat- ural elements of the four gospels as creative myths, a stance that led to his own expulsion from academe. Almost thirty years later, another scholar, the French- man Ernest Renan (1823-1892), published an even more controversial biography of Jesus, bringing its author similar academic exclusion but also huge commer- cial success. Like Strauss, Renan portrays Jesus as an amiable Galilean preacher whose life was later given mythic dimensions by his followers. Drawing on ex- tensive scriptural cross-referencing and historical evidence, however, Renan places even greater emphasis on the ordinariness of Jesus' background and early life, including in his book a speculative description of Jesus' village and the sug- gestion that he came from a typically large family. Embarrassed by the miracu- lous elements of the gospels, Renan concludes that Jesus would never have dreamt of passing himself off as divine, and that his healing and other so-called miracles were merely "performances" necessary to establish his preaching credi- bility alongside the other wonder-working rabbis of the day. Despite strong clerical opposition in his native France, Renan was eventUally restored to his seat in the prestigious College de France in 1870 and continued to write popular books about St. -

French Historians in the Nineteenth Century

French Historians in the Nineteenth Century French Historians in the Nineteenth Century: Providence and History By F.L. van Holthoon French Historians in the Nineteenth Century: Providence and History By F.L. van Holthoon This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by F.L. van Holthoon All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3409-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3409-4 To: Francisca van Holthoon-Richards TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Part 1 Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 Under the Wings of Doctrinaire Liberalism Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 12 Germaine de Staël on Napoleon Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 23 Le Moment Guizot, François Guizot Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

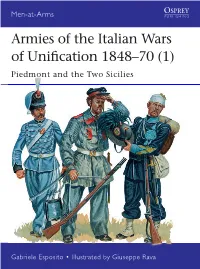

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

Postal Communications from the United Kingdom to Italy 1840 -1874

Postal Communications from the United Kingdom to Italy 1840 -1874 This exhibit addresses the postal communications between the United Kingdom and Italy, focusing on the complex historical period from 1840 to 1874. These dates saw the introduction Section 1 - Old States Frame of the first postage stamp (1840), the explosion of the industrial revolution in Britain, and the struggle of the Italian states to gain national unity after the Congress of Vienna. During this Chapter 1 - Kingdom of the Two Sicilies 1 time, new and much faster ways of communication (mostly the train and the steamship) co- Chapter 2 - Grand Duchy of Tuscany 1 existed with the remnants of old agreements, or in some cases the lack thereof, which allowed for the mail to be carried at different rates and through different routes and different countries. Chapter 3 - States of the Church & Rome 1 The result is a complex, fascinating array of rates and routes that this exhibit aims to describe. Chapter 4 - Duchies of Parma, Modena and Lucca 2 Chapter 5 - Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia 2 Chapter 6 - Kingdom of Sardinia 2 Section 2 – Kingdom of Italy Chapter 7 - New Nation: Countrywide Rates 3 Chapter 8 - New Challenges: Cholera 3 Chapter 9 - New Challenges: The Impact of War 3 The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) reshaped Europe Essential Bibliography 1. Jane and Michael Moubray: British Letter Mail to Overseas Destination 1840-1875. RPSL, London 2018 2. Lewis Geoffrey: The 1836 Anglo-French Postal Convention, The Royal Philatelic Society London, 2015. The first section covers rates and routes separately for each of the following major Old 3.