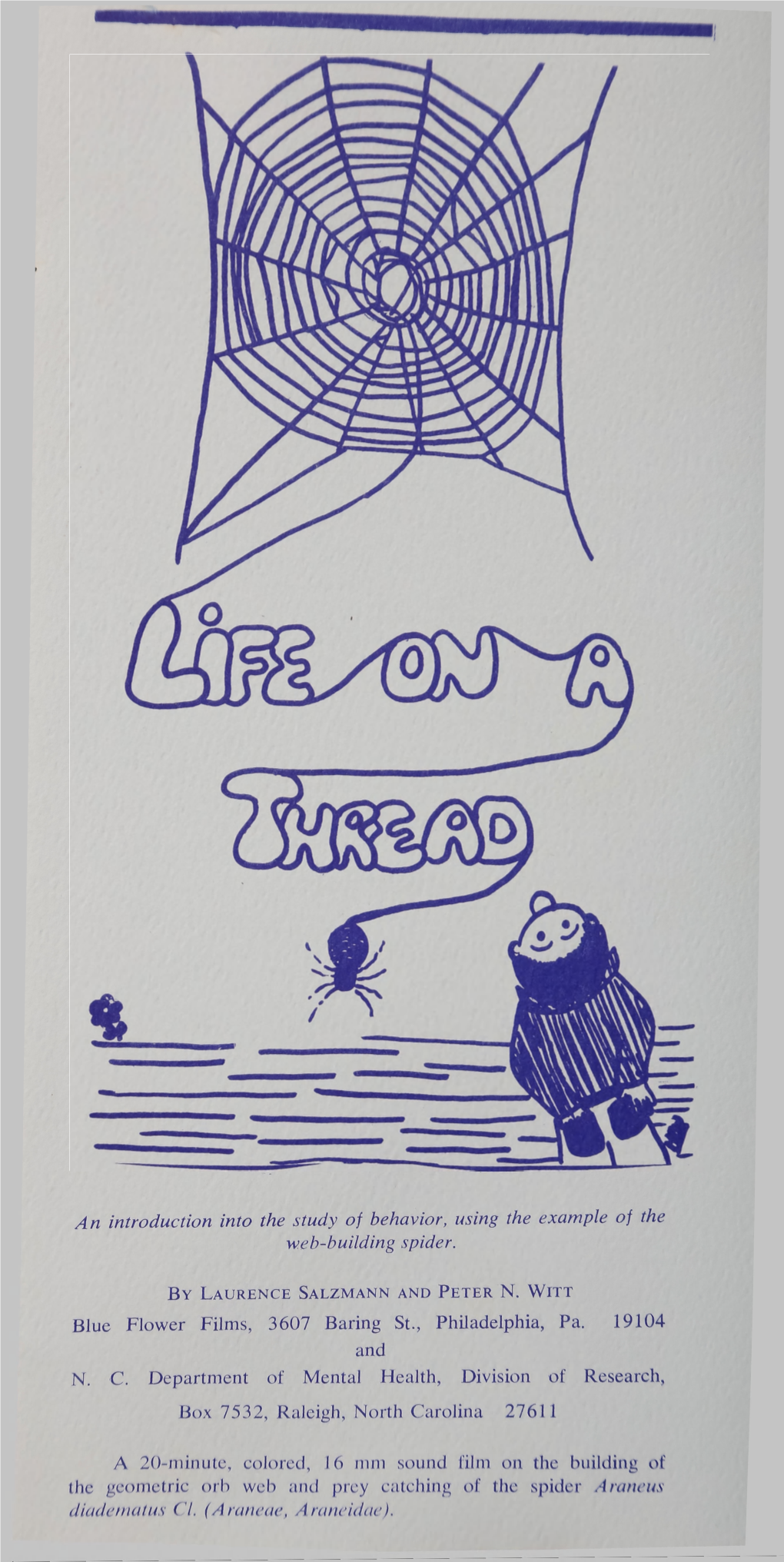

An Introduction Into the Study of Behavior, Using the Example of the W.Eb-Building Spider

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untangling Taxonomy: a DNA Barcode Reference Library for Canadian Spiders

Molecular Ecology Resources (2016) 16, 325–341 doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12444 Untangling taxonomy: a DNA barcode reference library for Canadian spiders GERGIN A. BLAGOEV, JEREMY R. DEWAARD, SUJEEVAN RATNASINGHAM, STEPHANIE L. DEWAARD, LIUQIONG LU, JAMES ROBERTSON, ANGELA C. TELFER and PAUL D. N. HEBERT Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada Abstract Approximately 1460 species of spiders have been reported from Canada, 3% of the global fauna. This study provides a DNA barcode reference library for 1018 of these species based upon the analysis of more than 30 000 specimens. The sequence results show a clear barcode gap in most cases with a mean intraspecific divergence of 0.78% vs. a min- imum nearest-neighbour (NN) distance averaging 7.85%. The sequences were assigned to 1359 Barcode index num- bers (BINs) with 1344 of these BINs composed of specimens belonging to a single currently recognized species. There was a perfect correspondence between BIN membership and a known species in 795 cases, while another 197 species were assigned to two or more BINs (556 in total). A few other species (26) were involved in BIN merges or in a combination of merges and splits. There was only a weak relationship between the number of specimens analysed for a species and its BIN count. However, three species were clear outliers with their specimens being placed in 11– 22 BINs. Although all BIN splits need further study to clarify the taxonomic status of the entities involved, DNA bar- codes discriminated 98% of the 1018 species. The present survey conservatively revealed 16 species new to science, 52 species new to Canada and major range extensions for 426 species. -

Araneus Bonali Sp. N., a Novel Lichen-Patterned Species Found on Oak Trunks (Araneae, Araneidae)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 779: 119–145Araneus (2018) bonali sp. n., a novel lichen-patterned species found on oak trunks... 119 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.779.26944 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Araneus bonali sp. n., a novel lichen-patterned species found on oak trunks (Araneae, Araneidae) Eduardo Morano1, Raul Bonal2,3 1 DITEG Research Group, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Toledo, Spain 2 Forest Research Group, INDEHESA, University of Extremadura, Plasencia, Spain 3 CREAF, Cerdanyola del Vallès, 08193 Catalonia, Spain Corresponding author: Raul Bonal ([email protected]) Academic editor: M. Arnedo | Received 24 May 2018 | Accepted 25 June 2018 | Published 7 August 2018 http://zoobank.org/A9C69D63-59D8-4A4B-A362-966C463337B8 Citation: Morano E, Bonal R (2018) Araneus bonali sp. n., a novel lichen-patterned species found on oak trunks (Araneae, Araneidae). ZooKeys 779: 119–145. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.779.26944 Abstract The new species Araneus bonali Morano, sp. n. (Araneae, Araneidae) collected in central and western Spain is described and illustrated. Its novel status is confirmed after a thorough revision of the literature and museum material from the Mediterranean Basin. The taxonomy of Araneus is complicated, but both morphological and molecular data supported the genus membership of Araneus bonali Morano, sp. n. Additionally, the species uniqueness was confirmed by sequencing the barcode gene cytochrome oxidase I from the new species and comparing it with the barcodes available for species of Araneus. A molecular phylogeny, based on nuclear and mitochondrial genes, retrieved a clade with a moderate support that grouped Araneus diadematus Clerck, 1757 with another eleven species, but neither included Araneus bonali sp. -

Untangling Taxonomy: a DNA Barcode Reference Library for Canadian Spiders

Received Date : 14-Mar-2015 Revised Date : 30-Jun-2015 Accepted Date : 06-Jul-2015 Article type : Resource Article Untangling Taxonomy: A DNA Barcode Reference Library for Canadian Spiders Gergin A. Blagoev Jeremy R. deWaard* Sujeevan Ratnasingham Article Stephanie L. deWaard Liuqiong Lu James Robertson Angela C. Telfer Paul D. N. Hebert Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada * Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: Accepted 10.1111/1755-0998.12444 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Keywords: DNA barcoding, spiders, Araneae, species identification, Barcode Index Numbers, Operational Taxonomic Units Abstract Approximately 1460 species of spiders have been reported from Canada, 3% of the global fauna. This study provides a DNA barcode reference library for 1018 of these species based upon the analysis of more than 30,000 specimens. The sequence results show a clear barcode gap in most cases with a mean intraspecific divergence of 0.78% versus a minimum nearest-neighbour (NN) distance averaging 7.85%. The sequences were assigned to 1359 Barcode Index Numbers (BINs) with 1344 of these BINs composed of specimens belonging to a single currently recognized Article species. There was a perfect correspondence between BIN membership and a known species in 795 cases while another 197 species were assigned to two or more BINs (556 in total). -

Araneae (Spider) Photos

Araneae (Spider) Photos Araneae (Spiders) About Information on: Spider Photos of Links to WWW Spiders Spiders of North America Relationships Spider Groups Spider Resources -- An Identification Manual About Spiders As in the other arachnid orders, appendage specialization is very important in the evolution of spiders. In spiders the five pairs of appendages of the prosoma (one of the two main body sections) that follow the chelicerae are the pedipalps followed by four pairs of walking legs. The pedipalps are modified to serve as mating organs by mature male spiders. These modifications are often very complicated and differences in their structure are important characteristics used by araneologists in the classification of spiders. Pedipalps in female spiders are structurally much simpler and are used for sensing, manipulating food and sometimes in locomotion. It is relatively easy to tell mature or nearly mature males from female spiders (at least in most groups) by looking at the pedipalps -- in females they look like functional but small legs while in males the ends tend to be enlarged, often greatly so. In young spiders these differences are not evident. There are also appendages on the opisthosoma (the rear body section, the one with no walking legs) the best known being the spinnerets. In the first spiders there were four pairs of spinnerets. Living spiders may have four e.g., (liphistiomorph spiders) or three pairs (e.g., mygalomorph and ecribellate araneomorphs) or three paris of spinnerets and a silk spinning plate called a cribellum (the earliest and many extant araneomorph spiders). Spinnerets' history as appendages is suggested in part by their being projections away from the opisthosoma and the fact that they may retain muscles for movement Much of the success of spiders traces directly to their extensive use of silk and poison. -

Sexual Cannibalism in the European Garden Spider Araneus Diadematus: the Roles of Female Hunger and Mate Size Dimorphism

Animal Behaviour 81 (2011) 749e755 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Sexual cannibalism in the European garden spider Araneus diadematus: the roles of female hunger and mate size dimorphism Helma Roggenbuck a,*, Stano Pekár b,1, Jutta M. Schneider a a Department of Biology, Zoological Institute and Museum, University of Hamburg b Department of Botany and Zoology, Faculty of Sciences, Masaryk University article info Sexual cannibalism, in particular before insemination, is a long-standing evolutionary paradox because it Article history: persists despite extreme costs for the victim, usually the male. Several adaptive and nonadaptive Received 10 May 2010 hypotheses have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, but empirical studies are still scarce and Initial acceptance 7 June 2010 results are inconclusive. We studied the spider Araneus diadematus in which females may attack and kill Final acceptance 5 January 2011 potential mates at any time during courtship or mating, making the species ideal for examining the Available online 16 February 2011 causes of pre- and postinsemination sexual cannibalism. We manipulated food availability for females MS. number: 10-00323R and conducted mating trials in the laboratory to test predictions derived from two hypotheses: the adaptive female foraging (AFF) hypothesis, which views sexual cannibalism as an optimal female Keywords: behaviour in the face of a trade-off between mating and cannibalizing a courting male; and the mate size adaptive female foraging dimorphism (MSD) hypothesis, which postulates a physical advantage of larger females in subduing Araneus diadematus males. We found partial support for the AFF hypothesis, but MSD explained sexual cannibalism irre- mate choice postinsemination spective of the timing of cannibalism. -

Spiders (Arthropoda: Aranea) from Deciduous Forest Litter of the Ouachita Highlands Peggy Rae Dorris Henderson State University

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 49 Article 11 1995 Spiders (Arthropoda: Aranea) From Deciduous Forest Litter of the Ouachita Highlands Peggy Rae Dorris Henderson State University Henry W. Robison Southern Arkansas University Chris Carlton Louisiana State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Dorris, Peggy Rae; Robison, Henry W.; and Carlton, Chris (1995) "Spiders (Arthropoda: Aranea) From Deciduous Forest Litter of the Ouachita Highlands," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 49 , Article 11. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol49/iss1/11 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 49 [1995], Art. 11 Spiders (Arthropoda: Aranea) From Deciduous Forest Litter of the Ouachita Highlands Peggy Rae Dorris Henry W. Robison Chris Carlton Department of Biology Department of Biology Department of Biology Henderson State University Southern Arkansas University Louisiana State University Arkadelphia, AR71999 Magnolia, AR 71753 Baton Rouge, LA70803 Abstract One hundred two litter samples were collected from oak/hickory and maple/beech forests in the Ouachita Highlands of western Arkansas July 1991-June 1992. -

Where Have All the Spiders Gone? Observations of a Dramatic

insects Communication Where Have All the Spiders Gone? Observations of a Dramatic Population Density Decline in the Once Very Abundant Garden Spider, Araneus diadematus (Araneae: Araneidae), in the Swiss Midland Martin Nyffeler 1,* and Dries Bonte 2 1 Department of Environmental Sciences, Section of Conservation Biology, University of Basel, CH–4056 Basel, Switzerland 2 Department of Biology, Terrestrial Ecology Unit, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] * Correspondence: martin.nyff[email protected] Received: 6 March 2020; Accepted: 10 April 2020; Published: 15 April 2020 Abstract: Aerial web-spinning spiders (including large orb-weavers), as a group, depend almost entirely on flying insects as a food source. The recent widespread loss of flying insects across large parts of western Europe, in terms of both diversity and biomass, can therefore be anticipated to have a drastic negative impact on the survival and abundance of this type of spider. To test the putative importance of such a hitherto neglected trophic cascade, a survey of population densities of the European garden spider Araneus diadematus—a large orb-weaving species—was conducted in the late summer of 2019 at twenty sites in the Swiss midland. The data from this survey were compared with published population densities for this species from the previous century. The study verified the above-mentioned hypothesis that this spider’s present-day overall mean population density has declined alarmingly to densities much lower than can be expected from normal population fluctuations (0.7% of the historical values). Review of other available records suggested that this pattern is widespread and not restricted to this region. -

Planarity and Size of Orb-Webs Built by Araneus Diadematus (Araneae: Araneidae) Under Natural and Experimental Conditions

EkolÛgia (Bratislava) Vol. 19, Supplement 3, 307-318, 2000 PLANARITY AND SIZE OF ORB-WEBS BUILT BY ARANEUS DIADEMATUS (ARANEAE: ARANEIDAE) UNDER NATURAL AND EXPERIMENTAL CONDITIONS SAMUEL ZSCHOKKE1,2,3, FRITZ VOLLRATH1,2,4 1 Department of Zoology, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, United Kingdom. 2 Zoologisches Institut, Universit‰t Basel, Rheinsprung 9, CHñ4051 Basel, Switzerland. 3 Institut f¸r Natur-, Landschafts- und Umweltschutz, Universit‰t Basel, St. Johanns-Vorstadt 10, CH-4056 Basel, Switzerland. Fax: +41 61 267 08 32. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Zoology, Universitetsparken B135, DKñ8000 Aarhus C, Denmark. 3 Address for correspondence Abstract ZSCHOKKE S., VOLLRATH F.: Planarity and size of orb-webs built by Araneus diadematus (Araneae: Araneidae) under natural and experimental conditions. In GAJDOä P., PEK¡R S. (eds): Proceedings of the 18th European Colloquium of Arachnology, Star· Lesn·, 1999. EkolÛgia (Bratislava), Vol. 19, Supplement 3/2000, p. 307-318. Orb-weaving spiders build more or less planar webs in a complex, three dimensional environ- ment. How do they achieve this? Do they explore all twigs and branches in their surroundings and store the information in some form of mental map? Or do they at first just build a cheap (i.e. few loops, possibly non-planar) web to test the site and ñ if this first web is successful (i.e. the web site is good) ñ later build subsequent improved and enlarged webs, by re-using some of the an- chor points and moving other anchor points? The second hypothesis is supported by the fact that the garden cross spider Araneus diadematus CLERCK (Araneidae) usually builds several webs at the same site, re-using structural parts of one web for subsequent webs. -

Common Spiders of the Chicago Region 1 the Field Museum – Division of Environment, Culture, and Conservation

An Introduction to the Spiders of Chicago Wilderness, USA Common Spiders of the Chicago Region 1 The Field Museum – Division of Environment, Culture, and Conservation Produced by: Jane and John Balaban, North Branch Restoration Project; Rebecca Schillo, Conservation Ecologist, The Field Museum; Lynette Schimming, BugGuide.net. © ECCo, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA [http://fieldmuseum.org/IDtools] [[email protected]] version 2, 2/2012 Images © Tom Murray, Lynette Schimming, Jane and John Balaban, and others – Under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License (non-native species listed in red) ARANEIDAE ORB WEAVERS Orb Weavers and Long-Jawed Orb Weavers make classic orb webs made famous by the book Charlotte’s Web. You can sometimes tell a spider by its eyes, most have eight. This chart shows the orb weaver eye arrangement (see pg 6 for more info) 1 ARANEIDAE 2 Argiope aurantia 3 Argiope trifasciata 4 Araneus marmoreus Orb Weaver Spider Web Black and Yellow Argiope Banded Argiope Marbled Orbweaver ORB WEAVERS are classic spiders of gardens, grasslands, and woodlands. The Argiope shown here are the large grassland spiders of late summer and fall. Most Orb Weavers mature in late summer and look slightly different as juveniles. Pattern and coloring can vary in some species such as Araneus marmoreus. See the link for photos of its color patterns: 5 Araneus thaddeus 6 Araneus cingulatus 7 Araneus diadematus 8 Araneus trifolium http://bugguide.net/node/view/2016 Lattice Orbweaver Cross Orbweaver Shamrock Orbweaver 9 Metepeira labyrinthea 10 Neoscona arabesca 11 Larinioides cornutus 12 Araniella displicata 13 Verrucosa arenata Labyrinth Orbweaver Arabesque Orbweaver Furrow Orbweaver Sixspotted Orbweaver Arrowhead Spider TETRAGNATHIDAE LONG-JAWED ORB WEAVERS Leucauge is a common colorful spider of our gardens and woodlands, often found hanging under its almost horizontal web. -

Phylogeny of the Orb‐Weaving Spider

Cladistics Cladistics (2019) 1–21 10.1111/cla.12382 Phylogeny of the orb-weaving spider family Araneidae (Araneae: Araneoidea) Nikolaj Scharffa,b*, Jonathan A. Coddingtonb, Todd A. Blackledgec, Ingi Agnarssonb,d, Volker W. Framenaue,f,g, Tamas Szuts} a,h, Cheryl Y. Hayashii and Dimitar Dimitrova,j,k aCenter for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; bSmithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution, NW Washington, DC 20560-0105, USA; cIntegrated Bioscience Program, Department of Biology, University of Akron, Akron, OH, USA; dDepartment of Biology, University of Vermont, 109 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405-0086, USA; eDepartment of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, WA 6986, Australia; fSchool of Animal Biology, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia; gHarry Butler Institute, Murdoch University, 90 South St., Murdoch, WA 6150, Australia; hDepartment of Ecology, University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest, H1077 Budapest, Hungary; iDivision of Invertebrate Zoology and Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA; jNatural History Museum, University of Oslo, PO Box 1172, Blindern, NO-0318 Oslo, Norway; kDepartment of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway Accepted 11 March 2019 Abstract We present a new phylogeny of the spider family Araneidae based on five genes (28S, 18S, COI, H3 and 16S) for 158 taxa, identi- fied and mainly sequenced by us. This includes 25 outgroups and 133 araneid ingroups representing the subfamilies Zygiellinae Simon, 1929, Nephilinae Simon, 1894, and the typical araneids, here informally named the “ARA Clade”. -

Zoologische Mededelingen

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN WELZIJN, VOLKSGEZONDHEID EN CULTUUR) Deel 57 no. 25 15 december 1983 THE DISTRIBUTION OF SPIDERS AND HARVESTMEN (CHELICERATA) IN THE DUTCH NATIONAL PARK "DE HOGE VELUWE" by L. VAN DER HAMMEN Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden ABSTRACT A preliminary study is made of the distribution of Araneida and Opilionida (Chelicerata) in a National Park in The Netherlands. Special attention is paid to the influence of vegetation struc- ture on the distribution of the spiders. In the late summer of 1944 and the autumn of 1946 a study was made of the distribution of spiders and harvestmen in the Dutch National Park "De Hoge Veluwe". The theme of this study was suggested to me by Dr. A. D. Voûte, at that time director of the Biological Laboratory, Hoenderloo. Some years before, Quispel (1941) had investigated the distribution of Ants in the same area. Westhoff & Westhoff-De Joncheere (1942; cf. also Westhoff, 1960), who continued Quispel's work with a study of distribution and nest- ecology of the ants in Dutch woods, characterized it as the first quantitative faunistic-sociological study in The Netherlands. Synecology was flourishing in The Netherlands at that time. Meitzer & Westhoff (1942) published an introduction to plant sociology, Westhoff, Dijk & Passchier (1942) a survey of the Dutch plant associations. Mörzer Bruyns (1947) published a theoretical introduction to biocenology, together with a biocenological study of terrestrial Mollusca. Van der Drift (1950) analysed the animal community in a beach forest floor in the National Park "De Hoge Ve• luwe" (before that time, Noordam & Van der Vaart-De Vlieger, 1943, had already studied the fauna of oak litter in that area). -

Novel Approaches to Exploring Silk Use Evolution in Spiders Rachael Alfaro University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Biology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 4-14-2017 Novel Approaches to Exploring Silk Use Evolution in Spiders Rachael Alfaro University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Alfaro, Rachael. "Novel Approaches to Exploring Silk Use Evolution in Spiders." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ biol_etds/201 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rachael Elaina Alfaro Candidate Biology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Kelly B. Miller, Chairperson Charles Griswold Christopher Witt Joseph Cook Boris Kondratieff i NOVEL APPROACHES TO EXPLORING SILK USE EVOLUTION IN SPIDERS by RACHAEL E. ALFARO B.Sc., Biology, Washington & Lee University, 2004 M.Sc., Integrative Bioscience, University of Oxford, 2005 M.Sc., Entomology, University of Kentucky, 2010 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosphy, Biology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2017 ii DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my grandparents, Dr. and Mrs. Nicholas and Jean Mallis and Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence and Elaine Mansfield, who always encouraged me to pursue not only my dreams and goals, but also higher education. Both of my grandfathers worked hard in school and were the first to achieve college and graduate degrees in their families.