Oliver Cromwell : Man of Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1St Half of Each Term HISTORY MTP Y4 Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Su

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1st half of each term HISTORY Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Summer 1: 6 WEEKS MTP Y4 Topic Title: Anglo-Saxons / Scots Topic Title: Vikings Topic Title: UK Parliament Taken from the Year Key knowledge: Key knowledge: Key knowledge: group • Roman withdrawal from Britain in CE • Viking raids and the resistance of Alfred the Great and • Establishment of the parliament - division of the curriculum 410 and the fall of the western Roman Athelstan. Houses of Lords and Commons. map Empire. • Edward the Confessor and his death in 1066 - prelude to • Scots invasions from Ireland to north the Battle of Hastings. Key Skills: Britain (now Scotland). • Anglo-Saxons invasions, settlements and Key Skills: kingdoms; place names and village life • Choose reliable sources of information to find out culture and Christianity (eg. Canterbury, about the past. Iona, and Lindisfarne) • Choose reliable sources of information to find out about • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, the past. backed up by evidence. • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, • Describe similarities and differences between people, Key Skills: backed up by evidence. events and artefacts. • Describe similarities and differences between people, • Describe how historical events affect/influence life • Choose reliable sources of information events and artefacts. today. to find out about the past. • Describe how historical events affect/influence life today. Chronological understanding • Give own reasons why changes may Chronological understanding • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE have occurred, backed up by evidence. • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE and and CE. -

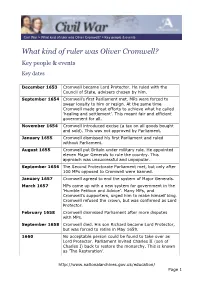

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Oliver Cromwell, Memory and the Dislocations of Ireland Sarah

CHAPTER EIGHT ‘THE ODIOUS DEMON FROM ACROSS THE sea’. OLIVER CROMWELL, MEMORY AND THE DISLOCATIONS OF IRELAND Sarah Covington As with any country subject to colonisation, partition, and dispossession, Ireland harbours a long social memory containing many villains, though none so overwhelmingly enduring—indeed, so historically overriding—as Oliver Cromwell. Invading the country in 1649 with his New Model Army in order to reassert control over an ongoing Catholic rebellion-turned roy- alist threat, Cromwell was in charge when thousands were killed during the storming of the towns of Drogheda and Wexford, before he proceeded on to a sometimes-brutal campaign in which the rest of the country was eventually subdued, despite considerable resistance in the next few years. Though Cromwell would himself depart Ireland after forty weeks, turn- ing command over to his lieutenant Henry Ireton in the spring of 1650, the fruits of his efforts in Ireland resulted in famine, plague, the violence of continued guerrilla war, ethnic cleansing, and deportation; hundreds of thousands died from the war and its aftermath, and all would be affected by a settlement that would, in the words of one recent historian, bring about ‘the most epic and monumental transformation of Irish life, prop- erty, and landscape that the island had ever known’.1 Though Cromwell’s invasion generated a significant amount of interna- tional press and attention at the time,2 scholars have argued that Cromwell as an embodiment of English violence and perfidy is a relatively recent phenomenon in Irish historical memory, having emerged only as the result of nineteenth-century nationalist (or unionist) movements which 1 William J. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663)

Ezra’s Archives | 35 A Rhetorical Convergence: Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663) Benjamin Cohen In October 1917, following the defeat of King Charles I in the English Civil War (1642-1649) and his execution, a series of republican regimes ruled England. In 1653 Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate regime overthrew the Rump Parliament and governed England until his death in 1659. Cromwell’s regime proved fairly stable during its six year existence despite his ruling largely through the powerful New Model Army. However, the Protectorate’s rapid collapse after Cromwell’s death revealed its limited durability. England experienced a period of prolonged political instability between the collapse of the Protectorate and the restoration of monarchy. Fears of political and social anarchy ultimately brought about the restoration of monarchy under Charles I’s son and heir, Charles II in May 1660. The turmoil began when the Rump Parliament (previously ascendant in 1649-1653) seized power from Oliver Cromwell’s ineffectual son and successor, Richard, in spring 1659. England’s politically powerful army toppled the regime in October, before the Rump returned to power in December 1659. Ultimately, the Rump was once again deposed at the hands of General George Monck in February 1660, beginning a chain of events leading to the Restoration.1 In the following months Monck pragmatically maneuvered England toward a restoration and a political 1 The Rump Parliament refers to the Parliament whose membership was composed of those Parliamentarians that remained following the expulsion of members unwilling to vote in favor of executing Charles I and establishing a commonwealth (republic) in 1649. -

Oliver Cromwell and the Regicides

OLIVER CROMWELL AND THE REGICIDES By Dr Patrick Little The revengers’ tragedy known as the Restoration can be seen as a drama in four acts. The first, third and fourth acts were in the form of executions of those held responsible for the ‘regicide’ – the killing of King Charles I on 30 January 1649. Through October 1660 ten regicides were hanged, drawn and quartered, including Charles I’s prosecutor, John Cooke, republicans such as Thomas Scot, and religious radicals such as Thomas Harrison. In April 1662 three more regicides, recently kidnapped in the Low Countries, were also dragged to Tower Hill: John Okey, Miles Corbett and John Barkstead. And in June 1662 parliament finally got its way when the arch-republican (but not strictly a regicide, as he refused to be involved in the trial of the king) Sir Henry Vane the younger was also executed. In this paper I shall consider the careers of three of these regicides, one each from these three sets of executions: Thomas Harrison, John Okey and Sir Henry Vane. What united these men was not their political views – as we shall see, they differed greatly in that respect – but their close association with the concept of the ‘Good Old Cause’ and their close friendship with the most controversial regicide of them all: Oliver Cromwell. The Good Old Cause was a rallying cry rather than a political theory, embodying the idea that the civil wars and the revolution were in pursuit of religious and civil liberty, and that they had been sanctioned – and victory obtained – by God. -

Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers 2017 Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda Lukas Dregne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dregne, Lukas, "Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda" (2017). Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers. 175. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp/175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dregne Just Warfare, or Genocide? Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda." Sir, the state, in choosing men to serve it, takes no notice of their opinions; if they be willing to serve it, that satisfies. I advised you formerly to bear with minds of different men from yourself. Take heed of being sharp against those to whom you can object little but that they square not with you in matters of religion. - Cromwell, To Major General Crawford (1643) Lukas Dregne B.A., History, Political Science University of Montana 1 Dregne Just Warfare, or Genocide? Abstract: Oliver Cromwell has always been a subject of fierce debate since his death on September 3, 1658. The most notorious stain blotting his reputation occurred during the conquest of Ireland by forces of the English Parliament under his command. -

Cromwell Study Guide for the Film of 1970

1 Cromwell Study Guide for the Film of 1970 Dr. Ron Fritze’s Tudor and Stuart Britain Course At Athens State University, Fall 2011 Semester Cromwell starring Richard Harris dramatized the role of Oliver Cromwell in the English Civil War, including his participation in the trial and execution of King Charles I. Unlike the Tudors, the Stuart dynasty has not attracted much cinematic interest, except for the playboy King Charles II in a minor way. It is important for Americans to understand that the English Civil War looms in the popular consciousness of the British people in much the same way as the American Civil War remains alive in the popular consciousness of Americans. Just as we have people who continue to debate the rights and the wrongs of the American Civil War, the British have people who debate the rights and wrongs of their civil war as well. We have re-enactors, they have re-enactors. The film treats the historical Oliver Cromwell sympathetically. Not all British and Irish would agree that he should be treated that way. In fact, Cromwell is the most hated figure in the Irish historical imagination. To prepare for viewing this film, take at look at the Wikipedia article on the film Cromwell. The article includes a list of some of the film’s historical inaccuracies. As you study this film, you should research and answer the questions below. They will help you write your compare-and-contrast paper. You will also find that the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the Historical Dictionary of Stuart England will help you with your background research. -

His Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax Major-General

The New Model Army December 1646 Commander: His Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax Major-General: Philip Skippon Lt General of Horse: Oliver Cromwell Lt General of the Ordnance: Thomas Hammond Commissary-General of Horse: Henry Ireton The Treasurers-at-War: Sir John Wollaston kt, Alderman Thomas Adams Esq, Alderman John Warner Esq, Alderman Thomas Andrews Esq, Alderman George Wytham Esq, Alderman Francis Allein Esq Abraham Chamberlain Esq John Dethick Esq Deputy-Treasurer-at-War: Captain John Blackwell Commissary General of Musters: Stane Deputy to the Commissary General of Musters: Mr James Standish Mr Richard Gerard Scoutmaster General: Major Leonard Watson Quartermaster-General of Foot: Spencer Assistant Quartermaster-General of Foot: Robert Wolsey Quartermaster-General of Horse: Major Richard Fincher Commissioners of Parliament residing with the Army: Colonel Pindar Colonel Thomas Herbert Captain Vincent Potter Harcourt Leighton Adjutant-Generals of Horse: Captain Christopher Flemming Captain Arthur Evelyn Adjutant-General of Foot: Lt Colonel James Grey Comptroller of the Ordnance: Captain Richard Deane Judge Advocate: John Mills Esq Secretary to the General and Soucil of War: John Rushworth Esq Chaplain to the Army: Master Bolles Commissary General of Victuals: Cowling Commissary General of Horse provisions: Jones Waggon-Master General: Master Richardson Physicians to the Army: Doctor Payne Doctor French Apothecary to the Army: Master Webb Surgeon to the General's Person: Master Winter Marshal-General of Foot: Captain Wykes Marshal-General -

A True Account of the New Model Army

Paul Z. Simons A True Account of the New Model Army 1995 Contents The Set Up . 3 The New Model Army . 4 What They Believed . 5 What They Did . 7 Where They Went . 9 Conclusion . 10 2 Revolutions have generally required some form of military activity; and mili- tary activity, in turn, generally implies an army or something like one. Armies, however, have traditionally been the offspring of the revolution, impinging little on the revolutionary politics that animate them. History provides numerous examples of this, but perhaps the most poignant is the exception that proves the rule. Recall the extreme violence with which rebellious Kronstadt was snuffed out by Bolshevism’s Finest, the Red Guards. The lesson in the massacre of the sailors and soldiers is plain, armies that defy the “institutional revolution” can expect nothing but butchery. The above statements, however, are generalizable solely to modernity, that is to say, only to the relatively contemporary era wherein the as- sumption that armies derive their mandate from the nation-state; and the nation- state in turn derives its mandate from “the people.” Prior to the hegemony of such assumptions, however, there is a stark and glaring example of an army that to a great degree was the revolution. Specifically an army that pushed the revolution as far as it could, an army that was the forum for the political development of the revolution, an army that sincerely believed that it could realize heaven on earth. Not a revolutionary army by any means, rather an army of revolutionaries, regicides, fanatics and visionaries. -

Essex Under Cromwell: Security and Local Governance in the Interregnum

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 1-1-2012 Essex under Cromwell: Security and Local Governance in the Interregnum James Robert McConnell Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the European History Commons, Military History Commons, and the Political History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation McConnell, James Robert, "Essex under Cromwell: Security and Local Governance in the Interregnum" (2012). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 686. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.686 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Essex under Cromwell: Security and Local Governance in the Interregnum by James Robert McConnell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Thesis Committee: Caroline Litzenberger, Chair Thomas Luckett David A. Johnson Jesse Locker Portland State University ©2012 Abstract In 1655, Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell’s Council of State commissioned a group of army officers for the purpose of “securing the peace of the commonwealth.” Under the authority of the Instrument of Government , a written constitution not sanctioned by Parliament, the Council sent army major-generals into the counties to raise new horse militias and to support them financially with a tax on Royalists which the army officers would also collect. In counties such as Essex—the focus of this study—the major-generals were assisted in their work by small groups of commissioners, mostly local men “well-affected” to the Interregnum government.