Explaining the Electoral Success of the AKP in Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Party Names Used in the Last 10 Years As Of: September 25, 2021

Page 1 of 6 Political Party Names Used in the Last 10 Years As of: September 25, 2021 Party Name Ballot Name Other Names Advocational International Democratic Advocational Party AID Party Party of British Columbia Advocates Advocational Democrats Advocational International Democratic Party Advocational International Democratic Party of BC Advocational Party of BC Advocational Party of British Columbia Democratic Advocates International Advocates B.C. New Republican Party Republican Party B.C. Vision B.C. Vision B.C. Vision Party BCV British Columbia Vision BC Citizens First Party BC Citizens First Party British Columbia Citizens First Party BC Ecosocialists BC Ecosocialists BC Eco-Socialists BC EcoSocialists BC Ecosocialist Alliance BC Ecosocialist Party BC First Party BC First BC Marijuana Party BC Marijuana Party British Columbia Marijuana Party Page 2 of 6 Political Party Names Used in the Last 10 Years As of: September 25, 2021 Party Name Ballot Name Other Names BC NDP BC NDP BC New Democratic Party BC New Democrats British Columbia New Democratic Party Formerly known as: New Democratic Party of B.C. NDP New Democratic Party New Democrats BC Progressive Party Pro BC BC Progressives Progressive Party BC Refederation Party BC Refed Formerly known as: Western Independence Party Formerly known as: Western Refederation Party of BC British Columbia Action Party BC Action Party BCAP British Columbia Direct Democracy British Columbia Direct BC Direct Party Democracy Party BC Direct Democracy Party Direct Democracy British Columbia Excalibur Party BC Excalibur Party British Columbia Liberal Party BC Liberal Party British Columbia Libertarian Party Libertarian Libertarian Party of BC British Columbia Party British Columbia Party BC Party BCP British Columbia Patriot Party B.C. -

TRANSFORMATION of POLITICAL ISLAM in TURKEY Islamist Welfare Party’S Pro-EU Turn

PARTY POLITICS VOL 9. No.4 pp. 463–483 Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi www.sagepublications.com TRANSFORMATION OF POLITICAL ISLAM IN TURKEY Islamist Welfare Party’s Pro-EU Turn Saban Taniyici ABSTRACT The recent changes in the Islamist party’s ideology and policies in Turkey are analysed in this article. The Islamist Welfare Party (WP) was ousted from power in June 1997 and was outlawed by the Consti- tutional Court (CC) in March 1998. After the ban, the WP elite founded the Virtue Party and changed policies on a number of issues. They emphasized democracy and basic human rights and freedoms in the face of this external shock. The WP’s hostile policy toward the European Union (EU) was changed. This process of change is discussed and it is argued that the EU norms presented a political opportunity structure for the party elites to influence the change of direction of the party. When the VP was banned by the CC in June 2001, the VP elites split and founded two parties which differ on a number of issues but have positive policies toward the EU. KEY WORDS European Union party change political Islam political oppor- tunity structure Turkey Introduction The Islamist Welfare Party (WP) in Turkey recently changed its decades-old policy of hostility toward the European Union (EU) and began strongly to support Turkey’s accession to the Union, thereby raising doubts about the inevitability of a civilizational conflict between Islam and the West. 1 This change was part of the party’s broader image transformation which took place after its leader, Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan,2 was forced by the Turkish political establishment to resign from a coalition government in June 1997. -

Full Text (PDF)

PEARSON JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES 2020 Doi Number :http://dx.doi.org/10.46872/pj.83 THE ROLE OF N. ERBAKAN AND THE WELFARE PARTY IN THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF TURKEY Dr. Namig Mammadov Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences ORCID: 0000-0003-4356-6111 Özet Bu makale, Necmettin Erbakan'ın ve Refah Partisi'nin modern Türkiye'nin siyasi tarihindeki rolünü incelemekte ve analiz etmektedir. Türkiye'de Milli Görüş Hareketi'nin oluşumunda ve gelişiminde ideoloji, sosyal taban ve ana itici güçler ile faaliyetleri de bu makalenin incelenme kısmıdır. Makale ayrıca hareketin önderi, önde gelen bilim adamı ve araştırmacısı, profesör Necmeddin Erbakan'ın rolü de dahil olmak üzere hareketin oluşumunu ve gelişimini etkileyen tarihsel koşulların yanı sıra siyasi arenaya girme nedenleri ve sonuçları da analiz ediyor. N. Erbakan'ın Türkiye'nin siyasi hayatındaki rolü araştırılarak değerlendirilmeye çalışılmıştır. Refah Partisi'nin ana ideolojisinin faizsiz bir serbest piyasa ekonomisi, üretimin güçlendirilmesi, temel insan haklarının korunduğu adil bir toplumun kurulması vb. olduğu kaydedilmiştir. Refah Partisi (RP), aynı yönü temsil eden Ahmet Tekdal liderliğinde 1983 yılında kuruldu. Siyasi yasakların kaldırılmasının ardından N. Erbakan yeniden parti başkanlığına seçildi. 1990'lar, Milli Görüş hareketinin gelişiminde yeni bir aşamaya geldi ve Refah Partisi'nin itibarı yükselmeye başladı. 1995 seçimlerinde parti oyların yüzde 21'ini kazandı. 1996 yılında N. Erbakan, Tansu Çiller liderliğindeki Doğru Yol Partisi ile koalisyon hükümeti kurdu. Bu hükümet 28 Şubat süreci sonucunda istifa etti ve parti feshedildi. Parti üyeleri Fazilet Partisi'ni kurdu. Anahtar kelimeler: Türkiye, N. Erbakan, Milli Görüş Hareketi, Milli Nizam Partisi, Refah Partisi Abstract This article examines and analyzes the role of Najmeddin Erbakan and the Welfare Party in the political history of modern Turkey. -

The Identity Crisis of the True Path Party Author(S): Ümit Cizre Sakallioğlu Source: Middle Eastern Studies, Vol

Liberalism, Democracy and the Turkish Centre-Right: The Identity Crisis of the True Path Party Author(s): Ümit Cizre Sakallioğlu Source: Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 32, No. 2 (Apr., 1996), pp. 142-161 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4283797 Accessed: 31-01-2019 17:02 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Middle Eastern Studies This content downloaded from 139.179.72.51 on Thu, 31 Jan 2019 17:02:58 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Liberalism, Democracy and the Turkish Centre-Right: The Identity Crisis of the True Path Party UMIT CIZRE SAKALLIOOLU In recent years there has been a sharp deflation of the left in political societies throughout the world. Accompanying this global trend has been the general acceptance of the primary tenets of neo-liberalism,' namely: political centrism; pragmatism; moderation; depoliticization; social and economic reforms that roll back the 'social' state; and the establishment of market capitalism. Neo- liberal ideas provided the impetus for the quality of political democracy and economic liberalization in post-1980 Turkey. -

The Cross-National Determinants of Legislative Party Switching

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2017 The rC oss-National Determinants of Legislative Party Switching Cassie Millet Knott Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Knott, Cassie Millet, "The rC oss-National Determinants of Legislative Party Switching" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4501. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4501 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CROSS-NATIONAL DETERMINANTS OF LEGISLATIVE PARTY SWITCHING A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Political Science by Cassie Millet Knott B.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2012 August 2017 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................ iii 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 2 Cross-National Analysis of Party Switching............................................................... -

Public Funding Solutions for Political Parties in Muslim-Majority Societies

Public Funding Solutions for Political Parties in Muslim-Majority Societies Writers Marcin Walecki Kevin Casas-Zamora Omer Genckaya Dina Ammar Chantal Sarkis-Hanna Karma Ekmekji-Boladian Elobaid Ahmed Elobaid. Public Funding Solutions for Political Parties in Muslim-Majority Societies Copyright © IFES. All rights reserved. IFES 1101 15th Street, NW Ste. 300 Washington, D.C. U.S.A. Notice of rights All rights reserved. No part of this report can be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-931459-34-7 P a g e | 1 Table of Contents Foreword .......................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements .......................................................................... 4 Biographies ....................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ........................................................................... 7 Introduction .................................................................................... 10 Dr. Kevin Casas-Zamora Part I Public Funding in Established and Transitional Democracies ......... 25 Dr. Marcin Walecki Part II Public Funding of Political Parties: ................................................. 39 The Case of Turkey Omer Faruk Genckaya Public Funding of Political Parties: .................................................. 50 The Case of Egypt Dina Ammar Public Funding for Political Parties: ................................................ -

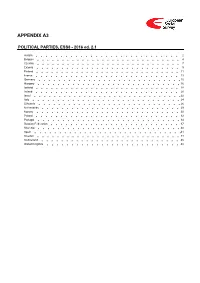

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Dynamics of the Queer Movement in Turkey Before and During The

Working Paper Research Group EU/Europe Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Zülfukar Çetin The Dynamics of the Queer Movement in Turkey before and during the Conservative AKP Government Working Paper , Research Group EU/Europe 2016/01, January 2016 SWP Berlin SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 3−4 10719 Berlin Telefon +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] SWP Working Papers do not undergo any formal peer review process. Translated by Daniel Hendrickson. Dr Zülfukar Çetin was IPC-Mercator Fellow at SWP from 2014 to 2015. The IPC-Stiftung Mercator Fellowship Program at SWP is supported by Stiftung Mercator. Table of contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 1. The History of the Queer Movement…………………………………………………. 6 1.1. The 1970s ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 1.2. The 1980s ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1.3. The 1990s ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 1.4. The 2000s ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 12 1.5. Post-Gezi ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 15 2. Demands of the Queer Movement …………………………………………………….. 16 2.1. Reforming the Criminal Code, Articles 3 and 122 …………………………… 16 2.2. Equal Treatment Requirement in Article 5 of the Labour Law ……….. 17 2.3. Discrimination in the Civil Code of November 22, 2001, in the version from May 15, 2014, Article 40 ……………………………………. 19 2.4. Discrimination by the Military Conscription Law ……………………………. 19 2.5. The Specific Demand “Equality before the Law”: Changes to Article 10 of the Constitution …………………………………………. 20 2.6. Demands with regard to due process ………………………………………………… 24 2.7. Demands with regard to the political system …………………………………… 24 3. -

Islamic Political Party Formation in Morocco, Turkey and Jordan A

Between Movement and Party: Islamic Political Party Formation in Morocco, Turkey and Jordan A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Esen Kirdi! IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Samuels Kathleen Collins July 2011 © Esen Kirdi! 2011 Acknowledgements I could have not written this dissertation without the intellectual, material and moral support of many people. I am indebted to all of them. In what follows, I will attempt the impossible task of acknowledging them all in a limited space such as this. As a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, I had the great opportunity to be a part of an intellectual community composed of a number of remarkable scholars and colleagues. I feel especially privileged and honored to have the chance to work closely with, and be mentored by, two wonderful advisors, David Samuels and Kathleen Collins. David Samuels’ Political Parties and Party Systems seminar played a central role in the framing of this project. It was in this seminar, I started researching about Islamic political parties. If David had not encouraged me to take the project further, this project would have remained as a seminar paper. I also thank David for his generosity with his time in commenting on multiple drafts of each chapter of this dissertation, his quick draft turnovers and patient replies to all my questions. David’s thoughtful comments and incisive criticisms urged me to see the bigger picture, and in doing so, helped me to express my thoughts more clearly. -

The Geography of AKP Votes

The Geography of AKP Votes Alpay Filiztekin and Ozan Bakis Sabanci University, Turkey Prepared for the 34th Annual Meeting of The Middle East Economic Association (MEEA), Philadelphia, PA January 3-5, 2014. Very preliminary. Please do not quote without authors' consent. The Geography of AKP Votes Alpay Filiztekin∗ and Ozan Bakisy Abstract The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey won three elections in a row by increasing its share of votes in each election. The political studies claim that this is mostly due to a transformation marked by the reshuffling of party preferences in favor of right-wing parties at the expense of the Center{right. Yet, AKP has also shown a remarkably good performance in terms of economic development. In 2002, after a severe economic crisis the newly formed AKP managed to establish macroeconomic stability with very high growth rates. Indeed, some early micro-studies find significant evidence of economic voting, albeit not as a strong predictor of its success as ideological orientation of voters. In this paper, using province and district level data, we are investigating support for AKP in successive elections. Particularly, we are examining geographic patterning and its evolution over time by employing spatial statistics which will allow us a deeper probing of regional and contextual elements. In studies based on micro-data space and context are implicit. We argue that voters make decisions within a context which has composites of structural (socio-economic) and spatial influences with multiple layers. Hence, regional heterogeneity in Turkey and local differences may have strong implications for voting. -

Species of Political Parties: a New Typology

PARTY POLITICS VOL 9. No.2 pp. 167–199 Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi SPECIES OF POLITICAL PARTIES A New Typology Richard Gunther and Larry Diamond ABSTRACT While the literature already includes a large number of party typologies, they are increasingly incapable of capturing the great diversity of party types that have emerged worldwide in recent decades, largely because most typologies were based upon West European parties as they existed in the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth centuries. Some new party types have been advanced, but in an ad hoc manner and on the basis of widely varying and often inconsistent criteria. This article is an effort to set many of the commonly used conceptions of parties into a coherent framework, and to delineate new party types whenever the existing models are incapable of capturing important aspects of contemporary parties. We classify each of 15 ‘species’ of party into its proper ‘genus’ on the basis of three criteria: (1) the nature of the party’s organization (thick/thin, elite-based or mass-based, etc.); (2) the programmatic orien- tation of the party (ideological, particularistic-clientele-oriented, etc.); and (3) tolerant and pluralistic (or democratic) versus proto-hegemonic (or anti-system). While this typology lacks parsimony, we believe that it captures more accurately the diversity of the parties as they exist in the contemporary democratic world, and is more conducive to hypothesis- testing and theory-building than others. KEY WORDS party organization party programmes party systems party types For nearly a century, political scientists have developed typologies and models of political parties in an effort to capture the essential features of the partisan organizations that were the objects of their analysis. -

Party Closures As a Measure of Militant Democracy in Turkey

Party Closures as a Measure of Militant Democracy in Turkey By Ozlem Ozcelik Submitted to the Central European University Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Prof. Nenad Dimitrijevic CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary (2014) Abstract The thesis explores the concept and practice of militant democracy in Turkey, with the focus on party closures. After its establishment in 1961, the Turkish Constitutional Court closed much higher number of political parties than other European countries that institutionalized militant democracy. Most of the parties that are closed by the Court are Kurdish nationalist, Islamist and socialist/communist parties. This thesis aims to find out the reason of this situation. First of all this study reveals that one of the reasons of the activism of the Court is the wide range of prohibitions offered by 1982 Constitution and the Law on Political Parties. By making analysis of the three party cases that represent three party categories frequently closed by the Turkish Constitutional Court, this study shows another reason of the frequent party closure practice in Turkey: the Court uses its power of interpretation to prioritize the state ideology as compared to freedom of assembly and association. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements Among the feelings that motivate us to take part in the academia despite all its sufferings, for me the most noble one is “compassion for others”. Like most of the signs of nobility, it is something that can be rarely observed. In this sense, I consider myself very lucky to have Nenad Dimitrijevic as my supervisor.