The HUMAN LIFE REVIEW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Notable Dates 2021

National Notable Dates 2021 The following are national commemorative days of relevance to The Royal Canadian Legion that raise awareness of an issue, commemorate a group or event, or celebrate something. Also included are national Legion activities. Branches may wish to promote these dates or organize related activities. Dominion Command promotes many of these dates through our social media channels. Selected commemorative dates may be promoted on significant anniversaries. We encourage Branches and members to share Legion national messaging from our social media channels: Facebook.com/CanadianLegion Twitter.com/RoyalCdnLegion Instagram.com/royalcanadianlegion JANUARY • 1 New Years Day • 27 Holocaust Remembrance Day • 28 Bell Let’s Talk (mental health) • Membership renewal reminders FEBRUARY • Black history month • 14 Valentines Day • Family Day (day varies by province) • 15 National Flag of Canada Day • 28 Gulf War ends (1991) - 30th anniversary • Lapsed member reminders MARCH • 3 World Hearing Day • 8 International Women’s Day • 2nd Monday - Commonwealth Day (RCEL support) • 15 Last Canadian soldiers return from Afghanistan (2014) APRIL • Month of the Military Child • 3 Battle of Moreuil Wood (1918) • 4 NATO Accord signed (1949) • 9 Battle of Vimy Ridge (1917) - Legion flags lowered to half mast • 18-24 National Volunteer Week • 21 Queens birthday 1926 • 25 Anzac Day • 25 Battle of Kapyong (1951) MAY • 1st Sunday Battle of the Atlantic (1945) • 1-7 National Youth Week • 3 John McCrae wrote ‘In Flanders Fields’ poem • 3-9 CMHA Mental -

National Family Week

87 STAT. ] PROCLAMATION 4172-NOV. 18, 1972 1141 business groups, labor unions, youth and women's clubs, schools, and other interested groups, to participate in this observance. I urge the Department of Agriculture, Jand-grant educational institutions, and all appropriate organizations and Government officials to mark the significance of National Farm-City Week with special events and activities. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this seventeenth day of November, in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred seventy-two, and of the Indepedence of the United States of America the one hundred ninety-seventh. PROCLAMATION 4172 National Family Week By the President of the United States of America November 18,1972 A Proclamation As prospects brighten for a lasting peace in the world, we can hope to approach more closely the age-old ideal of a single, harmonious family of man. As we work toward that great goal, however, we must never forget that our starting point—the center of our affections and the wellspring of our self-renewal—must be the basic family circle. Parent and child, husband and wife, brother and sister, all truly mean "home" to every human being. No institution can ever take the family's place in giving meaning to human life and a stable structure to society; indeed, as a wise philosopher > observed thousands of years ago, "the root of the state is in the family." The pressures of our modern age make this a time of challenge for fam ilies in America, but every community has its inspiring examples of families which have risen to the demand and made the time of challenge a time of glory. -

The Importance of the Catholic School Ethos Or Four Men in a Bateau

THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS OR FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ruth Joy August 2018 A dissertation written by Ruth Joy B.S., Kent State University, 1969 M.S., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Natasha Levinson _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Averil McClelland _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration ........................ _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human Services James C. Hannon ii JOY, RUTH, Ph.D., August 2018 Cultural Foundations ........................ of Education THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS. OR, FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU (213 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Natasha Levinson, Ph. D. Dozens of academic studies over the course of the past four or five decades have shown empirically that Catholic schools, according to a wide array of standards and measures, are the best schools at producing good American citizens. This dissertation proposes that this is so is partly because the schools are infused with the Catholic ethos (also called the Catholic Imagination or the Analogical Imagination) and its approach to the world in general. A large part of this ethos is based upon Catholic Anthropology, the Church’s teaching about the nature of the human person and his or her relationship to other people, to Society, to the State, and to God. -

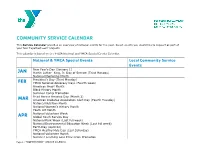

Community Service Calendar

COMMUNITY SERVICE CALENDAR This Service Calendar provides an overview of national events for the year. Select events you would like to support as part of your four Togetherhood® projects. This calendar is based on the Y-USA National and YMCA Special Events Calendar. National & YMCA Special Events Local Community Service Events New Year’s Day (January 1) JAN Martin Luther King, Jr. Day of Service (Third Monday) National Mentoring Month President’s Day (Third Monday) FEB YMCA National Advocacy Days (Fourth week) American Heart Month Black History Month Summer Camp Promotion Read Across America Day (March 2) MAR American Diabetes Association Alert Day (Fourth Tuesday) National Nutrition Month National Women’s History Month Youth Art Month National Volunteer Week APR Global Youth Service Day National Park Week (Last full week) National Environmental Education Week (Last full week) Earth Day (April 22) YMCA Healthy Kids Day (Last Saturday) National Volunteer Month Summer Learning Loss Prevention Promotion Page 1 | TOGETHERHOOD® SERVICE CALENDAR Mother’s Day, (Second Sunday) MAY National Women’s Health Week (First week) Armed Forces Day (Third Saturday) Memorial Day (Last Monday) National Senior Health & Fitness Day (Last Wednesday) National Water Safety Promotion Month Asian Pacific Heritage Month National Water Safety Month National Physical Fitness & Sports Month Older Americans Month Arthritis Awareness Month Graduations National Men’s Health Week (Second week) JUNE Summer Learning Day (Second Thursday) Father’s Day (Third Sunday) Back-to-School/Afterschool -

PROCLAMATION 6629—NOV. 24, 1993 107 STAT. 2765 National

PROCLAMATION 6629—NOV. 24, 1993 107 STAT. 2765 sis, we have recalled the importance of our national family tree, always returning to the promise of its protective shade. As families across the country gather in thanksgiving, it is particularly appropriate that we pause as a Nation to acknowledge the blessings of love and loyalty that families bring to their members and through them, to the community of America. Like oiu- democracy, all of our families must strive to be nurturing and steady. All of our children, grandparents, mothers and fathers must know that no matter the chal lenges we face, we can be secure in the love and support of a family. This lesson is among our foimders' most precious gifts. Fulfilling their ideal is each generation's most profound responsibility. The Congress, by House Joint Resolution 79, has designated the week of November 21, 1993, and the week of November 20, 1994, as "Na tional Family Week" and has authorized and requested the President to issue a proclamation in observance of these weeks. NOW, THEREFORE, I, WILLIAM J. CLINTON, President of the United States of America, do hereby proclaim the week of November 21, 1993, and the week of November 20, 1994, as National Family Week. I invite y the States, communities, £md people of the United States to observe these weeks with appropriate ceremonies and programs in appreciation of our Nation's families. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereimto set my hand this twenty-sec ond day of November, in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and ninety-three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two himdred and eighteenth. -

The Family, by E. Douglas Clark

“It is no exaggeration to say that in the Universal Declaration the family is at the very center of rights. The family is fundamental because, among other things, it is the seedbed of all the other rights delineated in the Universal Declaration. To make the world new following the devastation of the most destructive war in history, the UN built its structure of universal human rights squarely on the foundation of the family.” ––E. Douglas Clark, J.D. The author: E. Douglas Clark is an attorney and the Director of UN Affairs for the World Congress of Families sponsored by the Howard Center for Family, Religion and Society. Since 2001, Doug has been on the forefront of defending the family at the United Nations where he has played a key role as a lobbyist and consultant, helping to formulate strategy and providing legal advice in pivotal negotiations. He earned MBA and law degrees from Brigham Young University, and his legal career has included serving as Director of Content for the original Law.com website. Doug is also an avid student of religion and history, focusing on Islamic, Judaic and Christian traditions about Abraham and retracing his route through the Middle East. 8 The Family and the MDGs The Family E. Douglas Clark, J.D. On the morning of September 11, 2001, I arose in my Manhattan hotel and got ready for another day of the United Nations “PrepCom” (preparatory committee meeting) negotiations for the upcoming Special Session on Children—an event touching on family issues proving to be singularly divisive. -

Law, Judges and the Principles of Regimes: Explorations George Anastaplo Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected]

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2003 Law, Judges and the Principles of Regimes: Explorations George Anastaplo Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Anastaplo, George, Law, Judges and the Principles of Regimes: Explorations, 70 Tenn. L. Rev. 455 (2003) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAW, JUDGES, AND THE PRINCIPLES OF REGIMES: EXPLORATIONS t GEORGE ANASTAPLO* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................ 456 1. MACHIAVELLI, RELIGION, AND THE RULE OF LAW .............. 459 2. JUDGES, POLITICS, AND THE CONSTITUTION ................... 465 3. A PRIMER ON CONSTITUTIONAL ADJUDICATION ................ 468 4. BILLS OF RIGHTS-ANCIENT, MODERN, AND NATURAL 9. 475 5. THE MASS MEDIA AND THE AMERICAN CHARACTER ............ 481 6. POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY AND A SOFT CAESARISM ............... 491 7. THE PROPER OVERCOMING OF SELF-ASSERTIVENESS ............ 499 8. THE COMMON LAW AND THE JUDICIARY ACT OF 1789 ........... 511 9. A RETURN TO BARRON V. BALTIMORE ........................ 519 10. POLITICAL WILL, THE COMMON GOOD, AND THE CONSTITUTION.. 527 11. TOCQUEVILLE ON THE ROADS TO EQUALITY .................. 532 12. STATESMANSHIP AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAW ................ 546 t Law, Judges, and the Principlesof Regimes: Explorations is the first of two articles appearing in the Tennessee Law Review written by Professor Anastaplo. For the second of these two articles, see Constitutionalismandthe Good: Explorations,70 TENN. -

Family Support Centers

FAMILY SUPPORT CENTERS A Family Support Center is a place where everyone feels they are part of the family. Centers create opportunities for building strengths, accessing resources, connecting with others, and creating a sense of community. Family Support Centers work for social change by engaging families in addressing the issues that affect their lives. Who comes to a Family Support Center? Individuals looking for a sense of community and an opportunity to share gifts and learn something new. Children and Youth looking for a place to meet new friends, develop new skills, and share your talents. Families who want to spend time with other families to learn, have fun, and provide support. Community Groups who want to share resources and forge partnerships. Anyone who wants to make a difference in their community by volunteering. Everyone is Welcome at a Family Support Center • Parents receive support and share their interests! Parenting classes, support groups, parents’ and kids’ night out, resource libraries, and playgroups. • Neighbors become friends! Potluck dinners, weekend outings, block parties, and multi-cultural community celebrations. • Volunteers make a difference! Teach a class, organize a community event, chaperone a youth activity, and/or become a mentor or an advisor. • Kids feel important and become involved! After-school and homework clubs, art classes, music lessons, youth dances, and community service projects. • Everyone learns and grows! Reading clubs, exercise classes, early brain development, computer training, cooking and nutrition classes, English as a Second Language classes, information, and referrals for assistance. Who’s in Charge?...You! When you have an idea that will benefit you, your family or your community, the Family Center is there to help you make it happen! Each center is directed by community members (just like you) who serve on intergenerational advisory councils. -

The Faith and Morals of Justice Antonin Scalia

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Faculty Articles and Essays Faculty Scholarship 2019 The Faith and Morals of Justice Antonin Scalia David Forte Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Judges Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Forte, David, "The Faith and Morals of Justice Antonin Scalia" (2019). Law Faculty Articles and Essays. 1104. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles/1104 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Articles and Essays by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FAITH AND MORALS OF JUSTICE ANTONIN SCALIA DAVID F. FORTE* Both admirers and cntlcs call Antonin Scalia the most influential Supreme Court justice in the last half century. 1 He made originalism2 a legitimate tool of analysis for previously recalcitrant justices.3 Today, originalism is the stuff of the advocate's brief. 4 Antonin Scalia schooled his colleagues in the art of textual analysis, 5 * Professor of Law, Cleveland State University Cleveland-Marshall College of Law; B.A., Harvard College; M.A., University of Manchester; J.D., Columbia University; Ph.D., University ofToronto. I am grateful for the advice ofDr. Michael Uhlmann and for the assistance ofthe staff ofthe Cleveland-Marshall School of Law Library. -

From the Director

Southwestern Virginia Mental Health Institute NOVEMBER 1, 2012 From The Director Recovery 4 Heroes experienced challenges, losses when a disappointment or a and sadness, some of which we loss hits us over the head, it Chaplain’s 5 know about, and others we do makes more sense. As an Corner not know about because they are organization, our work is private sorrows. I was thinking precious, and each interaction Central Rehab 7 this week about an interaction I that we have with others can News had with one of our colleagues make a difference. The gift of who experienced a significant loss words of appreciation, admira- Time 9 this year. She was graciously tion, support, respect, and Change “It takes both rain and thankful for the time with her hope can fill up an empty sunshine to make a rainbow.” loved one, even through the heart. When we willingly bring Gym Game 12 pain. She reminded me that even our best selves, our thankful, Room Activities This year will soon be over; though we do not appreciate the sunshiny selves to each day, Personnel Thanksgiving is almost here. As cold and rainy times, the rain we have a better chance of 13 an organization, we have experi- helps us to appreciate the sun making a difference in others’ Changes enced many joys and successes. and the rainbows even more. lives. Our time on this earth History: “Old We have seen many individuals We are encouraged to take joy in is precious and what matters 14 Laundry” begin their recovery journey; we the sun while it shines as we most is that we use our days have seen many take the first step know that “Into each life some to their fullest and best and From the towards completing a Wellness rain must fall, some days be dark that we give something of our- 16 Library Recovery Action Plan, or make an and dreary.” ~ Longfellow) selves to others. -

Herald of Holiness Volume 72 Number 09 (1983)

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Herald of Holiness/Holiness Today Church of the Nazarene 5-1-1983 Herald of Holiness Volume 72 Number 09 (1983) W. E. McCumber (Editor) Nazarene Publishing House Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_hoh Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation McCumber, W. E. (Editor), "Herald of Holiness Volume 72 Number 09 (1983)" (1983). Herald of Holiness/ Holiness Today. 256. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_hoh/256 This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Church of the Nazarene at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Herald of Holiness/Holiness Today by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BENNER LIBRARY OLIVET NAZARENE COLLEGE JERALD KAKEE, ILLINOIS CHURCH OF THE NAZARENE / MAY 1, 1983 National Fam ily W eek May 1-7 AN EDITORIAL HE FINAL CHAPTER of the woman is circumspect in her own tude, but from the wonderful Book of Proverbs contains a appearance, dress, and conduct relationship found with Christ Jesus T beautiful description of a modeland, because of her sterling char in His saving and cleansing pres woman and a fitting tribute to moth acter and deportment, contributes ence. Jesus lives within, and His erhood. Though Solomon is accred to the standing and acceptance of abiding presence is far more satis ited with the writing of the first 29 her husband in the community. -

The Shadow of Natural Rights, Or a Guide from the Perplexed

Michigan Law Review Volume 86 Issue 6 1988 The Shadow of Natural Rights, or a Guide from the Perplexed Hadley Arkes Amherst College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Hadley Arkes, The Shadow of Natural Rights, or a Guide from the Perplexed, 86 MICH. L. REV. 1492 (1988). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol86/iss6/46 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SHADOW OF NATURAL RIGHTS, OR A GUIDE FROM THE PERPLEXED Hadley Arkes* AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION. By Walter Murphy, James Fleming and William Harris, IL Mineola: Foundation Press. 1986. Pp. 1212. $34.95. G.K. Chesterton once remarked that the problem with the world was not that it was unreasonable or even reasonable, but that "it is nearly reasonable, but not quite." He imagined a "mathematical crea ture from the moon" assaying the human body and being struck by its symmetry: a hand on the left side, matched by another on the right, with the same number of fingers; twin eyes, twin nostrils, twin lobes of the brain. "At last he would take it as a law; and then, where he found a heart on one side, would deduce that there was another heart on the other.