Petit Journal Van Caeckenbergh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrick Van Caeckenbergh

Patrick Van Caeckenbergh Expositions personnelles 2017 Les Nébuleuses - Mon Tout : les Etourdissements / Voyage autour de ma chambre, FRAC Provence - Alpes - Côte d'Azur, Marseille, FR Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent, BE 2016 Les Nébuleuses - Mon Tout : les Etourdissements, Musée Gassendi, Digne-les-Bains, FR 2015 Patrick Van Caeckenbergh, Lehman Maupin Gallery, New York, US Het Muziekbos, Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp Borgerhout, BE 2013 Les Nébuleuses - Mon Tout : les Etourdissements / Voyage autour de ma chambre, In Situ - fabienne leclerc, Paris, FR Patrick Van Caeckenbergh, Netwerk / Centrum voor Hedendaagse Kunst, Aalst, BE 2012 La ruine fructueuse, Museum M, Louvain, BE 2010 The bore thought, Nyehaus Gallery, New-York, US 2009 Le Brouhaha, In Situ - fabienne leclerc, Paris, FR 2007 Les bicoques, La Maison Rouge, Paris, FR Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature (collection permanente), Paris, FR 2006 Maquettes 1998-2006, Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp, BE 2005 Les Adoratoires, In Situ - fabienne leclerc, Paris, FR Atlas des idéations - Les jardins clos, Musée d'Art Contemporain, Nîmes, FR La peau est ce qu'il y a de plus profond, Musée des Beaux arts de Valenciennes, FR 2003 Les histoires naturelles, FRAC PACA, Marseille, FR In Situ - fabienne leclerc 43 rue de la Commune de Paris 93230 Romainville T. +33 (0)1 53 79 06 12 - [email protected] - www.insituparis.fr 2002 Les Nébuleuses, In Situ - fabienne leclerc, Paris, FR 2001 Le Dais - Le ciel à la portée de tous, Château d'Oiron, Oiron, FR Stil Geluk. Een keuze uit het werk 1980-2001, Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, NL 2000 De Anatomische Les - The Anatomy Lesson, Kabinet Overholland in het Stedelijk, Amsterdam, NL Stil Geluk, Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp, BE 1999 Die Schlupfwinkel (1979-1999), Kunstverein Bonn, DE 1998 Patrick Van Caeckenbergh, Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp, BE Patrick Van Caeckenbergh, Galerie des Archives, Paris, FR 1996 Jaarlijkse cultuurprijs van de Vlaamse gemeenschap / Annual prize of the Flemisch Community, Capitool, Gent, BE Het leven zelf. -

G Er T Ja Nv an R Oo Ij

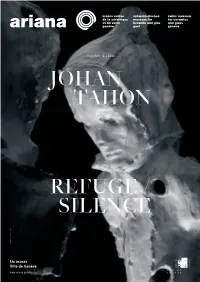

28.9.2019–5.4.2020 JOHAN TAHON REFUGE / SILENCE Photographie : Gert Jan van Rooij Press Kit 16 September 2019 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 Press visits on request only Exhibition preview Friday 27 September 2019 at 6pm Musée Ariana Swiss Museum for Ceramics and Glass 10, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva - Switzerland Press kit available at “Presse”: www.ariana-geneve.ch Visuals, photos on request: [email protected] Un musée Ville de Genève www.ariana-geneve.ch Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 CONTENTS Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE p. 3 Biography of Johan Tahon p. 4 Events p. 8 Practical information p. 9 2 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 J OHAN T AHON. REFUGE/SILENCE The Musée Ariana is proud to present Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE, in partnership with the Kunstforum gallery in Solothurn, from 28 September 2019 to 5 April 2020 in the space dedicated to contemporary creation. Johan Tahon, internationally renowned Belgian artist, is exhibiting a strong and committed body of work that reveals his deep connection with the ceramic medium. In the space devoted to contemporary creation, visitors enter a mystical world inhabited by hieratic monks, leading them into a second gallery where, in addition to the figures, pharmacy jars or albarelli are displayed. A direct reference to the history of faience, the ointments, powders and medicines contained in such vessels were intended to heal both body and soul. A sensitive oeuvre reflecting the human condition Johan Tahon’s oeuvre evolves in an original and individual way. -

PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Les Loques De Chagrin PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Les Loques De Chagrin Les Loques De Chagrin

PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Les Loques de Chagrin PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Les Loques de Chagrin Les Loques de Chagrin Zeno X Gallery stelt met trots Les Loques de Chagrin (De Smartlappen) voor, de tiende solotentoonstelling van Zeno X Gallery is proud to announce Les Loques de Chagrin (De Smartlappen), the tenth solo exhibition of Patrick Van Caeckenbergh (°1960, Aalst). Patrick Van Caeckenbergh (°1960, Aalst). Vanaf dit najaar zal zijn werk ook in dialoog treden met de collectie van het MSK te Gent. Daarenboven zal Van The Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent will host a solo presentation of his work in dialogue with the collection, Caeckenbergh zijn gehele studio ofwel ‘sigarenkistje’ aan het museum schenken, waar het een permanente opening in October 2017. Furhermore Patrick Van Caeckenbergh will donate his studio or so-called ‘cigar plek zal krijgen. box’ to the museum where it will be permanently on view. Patrick Van Caeckenbergh schematiseert, catalogiseert en brengt de wereld op een geheel eigen manier Patrick Van Caeckenbergh schematizes, catalogues and, in this way, renders the world in an entirely unique in kaart. Hij legt bijzondere parallellen bloot tussen wetenschappelijke theorieën, folkloristische verhalen, manner. He makes interesting parallels between scientific theories, folkloristic tales, mythologies and other mythologieën en andere narratieven. Hij formuleert alternatieve denkstructuren die vaak een zeer hedendaagse narratives. He formulates alternative thought patterns which are often very contemporary and critical. en kritische inslag hebben. The title of the exhibition derives from the installation Les Loques de Chagrin (La Vie d‘Esope). In the small De titel van de tentoonstelling is afkomstig van de installatie Les Loques de Chagrin (La Vie d’Esope). -

PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Het Muziekbos PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Het Muziekbos Het Muziekbos

PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Het Muziekbos PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Het Muziekbos Het Muziekbos ‘Het Muziekbos’ is reeds de negende solotentoonstelling van Patrick Van Caeckenbergh in bij Zeno X Het Muziekbos (The Musical Forest) is already the ninth solo exhibition of Patrick Van Caeckenbergh at Gallery. De laatste jaren werkte Van Caeckenbergh met enorme toewijding aan zijn project ‘Drawings of Zeno X Gallery. In recent years, Van Caeckenbergh has continued to work with tremendous dedication Old Trees’. Op de Biënnale van Venetië in 2013 werd er al een selectie van deze tekeningen getoond in het on his project Drawings of Old Trees. At the Venice Biennale in 2013, a selection of these drawings Arsenale en in Museum M werd het project voor het eerst in een museale context gepresenteerd. Met ‘Het was already shown in the Arsenale, followed by a showing in M Museum (Louvain, Belgium), the first Muziekbos’ wordt het project symbolisch afgerond. Een eerste deel werd eerder dit jaar plaats voorgesteld presentation of the project in a museum context. With Het Muziekbos, the project is brought to a in Lehmann Maupin Gallery n New York, die vanaf heden ook het werk van Patrick Van Caeckenbergh symbolic close. A first instalment was presented earlier this year at the Lehmann Maupin Gallery in New vertegenwoordigt. York, which from now on also represents the work of Patrick Van Caeckenbergh. In 1997 verhuist Patrick Van Caeckenbergh van Gent naar het kleine Sint-Kornelis-Horebeke. De nieuwe omgeving en het dorpsleven – een amalgaam van bewoners, mythes, gebeurtenissen en andere elementen In 1997, Patrick Van Caeckenbergh moved from Ghent to the small town of Sint-Kornelis-Horebeke. -

Press Kit "Felice Varini, Quatorze Triangles"

press release at la maison rouge June 1st to September 16th 2007 press preview Thursday May 31st 2007, 3pm to 6pm preview Thursday May 31st 2007, 6pm to 9pm Patrick van Caeckenbergh, Les Bicoques (Home Sweet Home) Seroussi Pavilion, architecture for a collector Felice Varini Flavio Favelli, Bureau September 12th to 16th Marie Cool and Fabio Balducci press relations la maison rouge Claudine Colin Communication fondation antoine de galbert Pauline de Montgolfier 10 bd de la bastille – 75012 Paris 5, rue Barbette – 75003 Paris www.lamaisonrouge.org [email protected] [email protected] t: +33 (0)1 42 72 60 01 t: +33 (0)1 40 01 08 81 f: +33 (0)1 42 72 50 23 f: +33 (0)1 40 01 08 83 contents p.3 presentation of la maison rouge the building the bookstore the café p.4 activities at la maison rouge the suite for children les amis de la maison rouge the vestibule publications p.5 Patrick van Caeckenbergh, Les Bicoques (Home Sweet Home) press release artist's biography selected works from the exhibition list of works p.9 The Seroussi Pavilion, architecture for a collector press release agencies taking part in the competition ancillary events p.15 Felice Varini press release p.17 the patio at la maison rouge, Flavio Favelli, Bureau press release p.19 practical info 2 presentation A private, non-profit foundation, la maison rouge opened in June 2004 in Paris. Its purpose is to promote contemporary creation through a programme of three solo or thematic temporary exhibitions a year, certain of which are staged by independent curators. -

Le Goût De L'art

REMERCIEMENTS À / THANKS TO Jocelyne Allain Delacour Ce catalogue est publié à l’occasion de l’exposition Veronique Barcelo LE GOÛT Le goût de l’Art présentée au Château du Rivau Claude Barthas du 4 avril au 2 novembre 2020 Géraldine et Lorenz Baumer Dans le cadre des Nouvelles Renaissances Armelle Blary en Region Centre-Val-de-Loire, Blackflag D E L’A R T Pour célébrer les 20 ans de l’inscription du Val de Loire Corine Borgnet — l’art du goût du — l’art sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial de l’Unesco, Lilian Bourgeat les 20 ans d’ouverture au public du Château du Rivau Denis et Solange Brihat et le 10ème anniversaire de l’inscription du repas gastronomique des Guillaume Blanc — l’art du goût français au Patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité par l’Unesco ChangKi Chung Eva Dalg Marie Denis DE L’ART This catalog is published on the occasion of the exhibition Lionel Estève Le goût de l’Art organised by Château du Rivau Bernard Estivin from the 4th of April to the 2nd of November 2020. Jean-Jacques Ezrati Sylvie Fredon As part of the Nouvelles Renaissances en Région Centre-Val-de-Loire, Galerie Air de Paris To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the inscription of the Loire Valley on Jacques Halbert GOÛTLE the UNESCO World Heritage List, the 20th anniversary of the opening of Maguelone Hédon the Château du Rivau to the public and the 10th anniversary of the ins- AEROPLASTICS Jérôme Jacobs cription of the French gastronomic meal as part of the Intangible Cultural Galerie Da-End Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. -

PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH LE MONDE À L’ENVERS PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Le Monde À L’Envers Le Monde À L’Envers

PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH LE MONDE À L’ENVERS PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH PATRICK VAN CAECKENBERGH Le Monde à l’Envers Le Monde à l’Envers Zeno X Gallery stelt met trots Le Monde à l’Envers voor, de elfde solotentoonstelling van Patrick Van Zeno X Gallery is proud to present Le Monde à l’Envers, Patrick Van Caeckenbergh’s eleventh solo Caeckenbergh sinds hij de galerij vervoegde in 1987. exhibition since he joined the gallery in 1987. Patrick Van Caeckenbergh schematiseert, catalogeert en brengt de wereld op een geheel eigen manier Patrick Van Caeckenbergh schematizes, catalogues and maps out the world in his own unique way. He in kaart. Hij legt bijzondere parallellen bloot tussen wetenschappelijke theorieën, folkloristische verhalen reveals particular parallels between scientific theories, folk tales and mythologies. He formulates alternative en mythologieën. Hij formuleert alternatieve denkstructuren die vaak een zeer hedendaagse en kritische thought structures that are often very topical and critical. inslag hebben. Le Monde à l’Envers brings together various installation works and models that emphasize the importance Le Monde à l’Envers brengt verschillende installatieve werken en maquettes samen die het belang van of caring, on both a personal and global level. The figure of the shaman plays a leading role in many of zorgzaamheid benadrukken, op persoonlijk vlak en op wereldniveau. De figuur van de sjamaan speelt the works. For Patrick Van Caeckenbergh, the shaman is an intermediary or threshold figure with whom in veel van de werken een hoofdrol. De sjamaan is voor Patrick Van Caeckenbergh een tussenpersoon he identifies; like the artist, the shaman finds himself on the border between two worlds that he tries to of drempelfiguur met wie hij zichzelf identificeert; net als de kunstenaar bevindt de sjamaan zich op de bring into contact with each other.