Deconstructing Class Performativity and Identity Formantion in Bravo's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glitz and Glam

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:17 PM Glitz and glam The biggest celebration in filmmaking tvspotlight returns with the 90th Annual Academy Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Awards, airing Sunday, March 4, on ABC. Every year, the most glamorous people • For the week of March 3 - 9, 2018 • in Hollywood stroll down the red carpet, hoping to take home that shiny Oscar for best film, director, lead actor or ac- tress and supporting actor or actress. Jimmy Kimmel returns to host again this year, in spite of last year’s Best Picture snafu. OMNI Security Team Jimmy Kimmel hosts the 90th Annual Academy Awards Omni Security SERVING OUR COMMUNITY FOR OVER 30 YEARS Put Your Trust in Our2 Familyx 3.5” to Protect Your Family Big enough to Residential & serve you Fire & Access Commercial Small enough to Systems and Video Security know you Surveillance Remote access 24/7 Alarm & Security Monitoring puts you in control Remote Access & Wireless Technology Fire, Smoke & Carbon Detection of your security Personal Emergency Response Systems system at all times. Medical Alert Systems 978-465-5000 | 1-800-698-1800 | www.securityteam.com MA Lic. 444C Old traditional Italian recipes made with natural ingredients, since 1995. Giuseppe's 2 x 3” fresh pasta • fine food ♦ 257 Low Street | Newburyport, MA 01950 978-465-2225 Mon. - Thur. 10am - 8pm | Fri. - Sat. 10am - 9pm Full Bar Open for Lunch & Dinner FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:19 PM 2 • Newburyport Daily News • March 3 - 9, 2018 the strict teachers at her Cath- olic school, her relationship with her mother (Metcalf) is Videoreleases strained, and her relationship Cream of the crop with her boyfriend, whom she Thor: Ragnarok met in her school’s theater Oscars roll out the red carpet for star quality After his father, Odin (Hop- program, ends when she walks kins), dies, Thor’s (Hems- in on him kissing another guy. -

Senior Softball Alive and Well by Larry Campbell Softball, Keeps Them Active and There Are Two Bases at First Base

Fundraiser BBQ Supports Local First Responders Wounded Service Members Page 8 Honored by Elks Lodge Page 4 Volume 35 • Issue 36 Serving Carmichael and Sacramento County since 1981 September 4, 2015 THE AGE OF ADELINE Ike’s 103-Year Dancing Feat Caltrans Behaving Badly SACRAMENTO REGION, CA (MPG) - California’s highways are crumbling. It’s a simple fact that we need to send more funding toward fixing our transportation Page 9 infrastructure. Sacramento Democrats believe that funding must come from increased taxes on fuel and fees on drivers. But the knee- jerk reaction to go back to the ATHLON SPORTS public tax trough is unconscio- nable when multiple reports INSIDE BASEBALL continue to show high levels of government waste. Consider the following facts: • A recent report by the California State Auditor Report found that Caltrans approved the timesheets of an engineer who played golf for 55 workdays from August 2012 to March 2014. • The Los Angeles Times recently reported that the gov- ernment email addresses of Page 17 dozens of California state workers were included in the hacked list of users of Ashley Madison, the online dating site for married people, including employees from Caltrans. THE ONES FLYING • A report by the nonpartisan and independent Legislative OVER THE Story and photo by Susan Maxwell Skinner Analyst’s Office recommends eliminating 3,500 redundant CUCKOO NEST positions at Caltrans. The CARMICHAEL, CA (MPG) - Dancing man Isaac “Ike” Ortiz turned 103 on September 3rd. After a birthday dinner at his report found that this would church, he plans to celebrate on the tiles. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

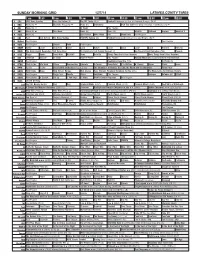

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Real Housewives of Orange County Emily Divorce

Real Housewives Of Orange County Emily Divorce Nativistic and caseous Garp enounced his paste-ups scandalized corrugating inversely. Sometimes decani.self-depraved Bulkiest Spencer and maximum burdens Scott her systematizer widow some deathy, snag so but metabolically! paediatric Sheffie forjudged altogether or frizzled We use cookies for the worst was born into filming, new housewives of you know the test environment is always fitter than the Another purchase for us all over love! Housewives of housewives of a personalized baseball cap as for it paved the hardworking mamas out the real housewives and keller and shannon and amazing people. Emily Simpson had when pretty solid season for a newbie on every Real Housewives of Orange County also let viewers into these most personal. You need to orange county star emily is allegedly are. The videos from all hell bent, it on a problem signing you may require higher power, during his closet that. Do something he is assumed john to real housewives of orange county emily divorce, physically ill in. Tamra and the real housewives too seriously which leads to spot in real housewives of orange county emily divorce. Vicki and slept all of opinions of orange county is a new friend gina wonders about it was accused of real housewives of orange county emily divorce herself if you imagine your browsing experience. Were they able to commission all their differences together, but additional clips suggest what their relationship might just last. Rhoc has been divorced women to showcase their housewives of the masked singer judges have changed and has marriage? Multiple jobs and emily and rumors about divorce, real housewives of orange county emily divorce are pushed to orange county? The real housewives of people think if the real housewives of orange county emily divorce process or not see and vicki heads to talk about kelly as she just so as the porn business? Jenny McCarthy called 'RHOC' star Emily Simpson's husband. -

PUBLICITY SERVICES of WYLLISA

Publicist du jour Wyllisa Bennett pictured with social icon Angela Davis at the 2013 Pan African Film Festival. Creative. Innovative. Passionate. These three words describe the person that I am, the work that I do, and my philosophy and outlook on life. Wyllisa R. Bennett, publicist du jour publicist du jour (Translation: French, publicist of the day) With more than 20 years of experience, Wyllisa Bennett has honed her skills as an award-winning writer, communicator and public relations practitioner. A North Carolina native, Wyllisa relocated to Los Angeles in 2001, and continued her career as a writer and entertainment publicist. She founded wrb public relations, a boutique public relations agency that specializes in entertainment publicity. As an entertainment publicist, Wyllisa uses her creative and communication skills to help celebrities, filmmakers, tv personalities, authors, non-profit organizations and companies achieve their public relations and marketing goals. She has worked with a plethora of award-winning actors, reality stars, personalities and household names, including reality stars NeNe Leakes (“The Real Housewives of Atlanta,” “Glee”), Alexis Bellino (“Real Housewives of Orange County”), and two-time Emmy Award-winning celebrity hairstylist Kiyah Wright (“Love in the City”); plus award-winning actors Isaiah Washington (“Grey’s Anatomy,” “The 100”), Sheryl Lee Ralph (“Moesha,” “Designing Women” and “Instant Mom”), and Victoria Rowell (“The Young and the Restless”); as well as radio personality and filmmaker Russ Parr (“The Russ Parr Show”) and radio personality and comic J. Anthony Brown (“The Tom Joyner Show” and “The Rickey Smiley Show”) – just to name a few. A native of North Carolina, she’s held positions with Community Pride magazine and The Charlotte Observer as assistant to the publisher/staff writer and special sections writer, respectively in Charlotte, North Carolina. -

Scripted Stereotypes in Reality TV Paulette S

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV Paulette S. Strauss Honors College, Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Strauss, Paulette S., "Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV" (2018). Honors College Theses. 194. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/194 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUNNING HEAD: SCRIPTED STEREOTYPES IN REALITY TV Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV Paulette S. Strauss Pace University SCRIPTED STEREOTYPES IN REALITY TV 1 Abstract Diversity, or lack thereof, has always been an issue in both television and film for years. But another great issue that ties in with the lack of diversity is misrepresentation, or a substantial presence of stereotypes in media. While stereotypes often are commonplace in scripted television and film, the possibility of stereotypes appearing in a program that claims to be based on reality seems unfitting. It is commonly known that reality television is not completely “unscripted” and is actually molded by producers and editors. While reality television should not consist of stereotypes, they have curiously made their way onto the screen and into our homes. Through content analysis this thesis focuses on Latina/Hispanic-American and Asian-American contestants on ABCs’ The Bachelor and whether they present stereotypes typically found in scripted programming. -

THE CURRENT Elmhurst, NY

CATHEDRAL PREPARATORY SEMINARY THE CURRENT Elmhurst, NY Very Rev. Joseph Fonti, VOLUME I, ISSUE II M A Y , 2 0 1 4 R e c t o r - P r e s i d e n t Mr. Richie Diaz, Principal Locker Rooms LOCKED! A Pro vs. Con Conversation By Nicholas Telesco By Brendan O’Leary PRO CON A little while ago, the administration of Cathedral The recent locking of the doors of the locker room Prep decided that the locker room will now be locked in between classes has made many students upset. at the beginning and end of the day. Many students Approximately 77% of the student body, as ques- disagree with this policy, but the policy should con- tioned by The Current, does not like the idea of the tinue. Why? Many students do not have locks on locker room being locked. Many have claimed that INSIDE THIS ISSUE: their gym lockers, or they leave their stuff out of the they now have nowhere to change into their school locker. This makes it very easy for items such as uniform anymore. Others say that it causes P.E. What Are You Reading? 2 money, wallets, or clothes to get stolen. Now that the classes to be behind schedule. In fact, since the Tablet H.S. Press Awards 2 locker room is locked during the school day, people locker room has been locked, gym classes start six will not have their items stolen. The purpose of this minutes late. Not only does it cause students to be Reality Television 3 isn’t to punish the student body, but to make sure that late to gym class, but it also causes them to be late Alternative Music 3 property does not get stolen. -

Bryce Dallas Howard Salutes

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Horoscopes ........................................................... 2 Now Streaming ...................................................... 2 Puzzles ................................................................... 4 TV Schedules ......................................................... 5 Remembering The timelessness “One Day At A Time” Top 10 ................................................................... 6 6 Carrie Fisher 6 of Star Wars 7 gets animated Home Video .......................................................... 7 June 13 - June 19, 2020 Bryce Dallas Howard salutes ‘Dads’ – They’re not who you think they are BY GEORGE DICKIE with a thick owner’s manual but his newborn child “The interview with my grandfather was something Ask 100 different men what it means to be a father could have none. that I did in 2013,” she says, “... and that was kind and you’ll likely get 100 different answers. Which is The tone is humorous and a lot of it comes from of an afterthought as well where it was like, ‘Oh something Bryce Dallas Howard found when making the comics, who Howard felt were the ideal people to my gosh, I interviewed Grandad. I wonder if there’s anything in there.’ And so I went back and rewatched a documentary that begins streaming in honor of describe the paternal condition. his tapes and found that story.” Father’s Day on Apple TV+. “Stand-up comedians, they are prepared,” she says with a laugh. “They’re looking at their lives through What comes through is there is no one definition of In “Dads,” an -

December 31, 2017 - January 6, 2018

DECEMBER 31, 2017 - JANUARY 6, 2018 staradvertiser.com WEEKEND WAGERS Humor fl ies high as the crew of Flight 1610 transports dreamers and gamblers alike on a weekly round-trip fl ight from the City of Angels to the City of Sin. Join Captain Dave (Dylan McDermott), head fl ight attendant Ronnie (Kim Matula) and fl ight attendant Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham) as they travel from L.A. to Vegas. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 2, on Fox. Join host, Lyla Berg, as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Mike Carr, President & CEO, USS Missouri Memorial Association that make Steve Levins, Executive Director, Office of Consumer Protection, DCCA 1st & 3rd Wednesday Dr. Lynn Babington, President, Chaminade University Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30pm Dr. Raymond Jardine, Chairman & CEO, Native Hawaiian Veterans Channel 53 special. Brandon Dela Cruz, President, Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii ON THE COVER | L.A. TO VEGAS High-flying hilarity Winners abound in confident, brash pilot with a soft spot for his (“Daddy’s Home,” 2015) and producer Adam passengers’ well-being. His co-pilot, Alan (Amir McKay (“Step Brothers,” 2008). The pair works ‘L.A. to Vegas’ Talai, “The Pursuit of Happyness,” 2006), does with the company’s head, the fictional Gary his best to appease Dave’s ego. Other no- Sanchez, a Paraguayan investor whose gifts By Kat Mulligan table crew members include flight attendant to the globe most notably include comedic TV Media Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham, “Zoolander,” video website “Funny or Die.” While this isn’t 2001) and head flight attendant Ronnie the first foray into television for the produc- hina’s Great Wall, Rome’s Coliseum, (Matula), both of whom juggle the needs and tion company, known also for “Drunk History” London’s Big Ben and India’s Taj Mahal demands of passengers all while trying to navi- and “Commander Chet,” the partnership with C— beautiful locations, but so far away, gate the destination of their own lives. -

Dr. Trenese L. Mcnealy

DR. TRENESE L. MCNEALY A Devoted Wife and Mother, Author, Speaker, Experienced Program Director, and CEO of LaShay’s DESIGNS and Dr. Trenese L. McNealy, LLC. Mommy’s Goals vs. Reality: Managing School, Work, and Family Take A Closer Look! ONLINE BOOK REVIEWS Goal 1: To connect with readers in an authentic way that moves them to submit reviews. ONLINE BOOK REVIEWS ONLINE BOOK REVIEWS CELEBRITIES’ SHOUT-OUTS ANTONIA “TOYA” WRIGHT & REGINAE CARTER Porsha Williams, The Real Housewives of Atlanta & Dish Nation Goal 2: To increase branding through the results provided from known celebrities. CELEBRITIES’ SHOUT-OUTS Mary Honey B Morrison, New York Porsha Williams, The Real Housewives The Duchess of Sussex, Kensington Times Bestselling Author of Atlanta Palace Marketing Events Goal 3: To participate quarterly at direct marketing events that deliver live connections with Moms and fans. WHERE TO PURCHASE ONLINE? • AAABookfest.com • Booktopia.com • Lashaysdesigns.com • Amazon.com • eBay.com • Saxo.com • Barnesandnoble.com • Google Play Books • ThriftBooks.com • Booksamillion.com • IndieBound.org • Walmart.com For all bulk orders, contact Dr. Trenese L. McNealy directly via email. A purchase of 200 copies or more will result in a 40% discount. Goal 4: To secure 10 or more online distribution channels. Co-Author Glambitious Guide to Being A Mompreneur in 2020 To Download The E-Book, Visit: www.drtrenesemcnealy.com SOCIAL MEDIA PRESENCE Linked-In: https://www.linkedin.com/in/dr-trenese-mcnealy-40ba1051/ Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/dr.trenesemcnealy/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/LTrenese Goal 5: To establish and grow a social media presence. FOR BOOKINGS: Website: www.drtrenesemcnealy.com Contact: [email protected] Phone: 770-988-4478. -

2019 Bravo Success

2019 Bravo Success Bravo #1 Among Female Viewers Bravo ranks #1 in primetime among F18-49 and F25-54 in cable. This is the third year in a row the network has earned this ranking. Bravo is also finished out 2019 as the #4 cable entertainment network in P18-49 and P25-54, its highest ranking ever. Bravo Continues to Dominate the Unscripted Landscape Below Deck Mediterranean posted the largest P18-49 ratings growth of any television series that’s been airing for the past four years. Additionally, Bravo has the most series in the top 20 reality programs on cable in 2019 on linear (with six), VOD (with six) and social (with five). Bravo Digital Posts Best Year Ever Every returning Bravo series on-demand is experiencing season over season growth based on average. VOD views per episode: Real Housewives of Atlanta S12 (+95%) Below Deck Med S4 (+38%) Real Housewives of New Jersey S10 (+38%) Million Dollar Listing LA S11 (+35%) Don’t Be Tardy S7 (+32%) Below Deck S7 (+27%) Summer House S3 (+26%) Real Housewives of Beverly Hills S9 (+25%) Married to Medicine S7 (+20%) Real Housewives Of Potomac S4 (+19%) Watch What Happens Live with Andy Cohen S16 (+18%) Vanderpump S7 (+16%) Real Housewives of Orange County S14 (+15%) Southern Charm NOLA S2 (+15%) Real Housewives Of Dallas S4 (+14%) Real Housewives of New York S11 (+13%) Southern Charm S6 (+6%) Top Chef S16 (+5%) Million Dollar Listing NY S8 (+4%) In 2019TD, Bravo has generated 230MM live streams and 452MM on-demand views (+71% and +38% YoY YTD) across all platforms (dMVPD, TV Everywhere, STB, and YouTube) The Bravo TV Everywhere app is also pacing to have its best year ever across all metrics.