Dean's Circle 2019 – Ust Faculty of Civil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Quezon City Public Library

HISTORY OF QUEZON CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY The Quezon City Public Library started as a small unit, a joint venture of the National Library and Quezon City government during the incumbency of the late Mayor Ponciano Bernardo and the first City Superintendent of Libraries, Atty. Felicidad Peralta by virtue of Public Law No. 1935 which provided for the “consolidation of all libraries belonging to any branch of the Philippine Government for the creation of the Philippine Library”, and for the maintenance of the same. Mayor Ponciano Bernardo 1946-1949 June 19, 1949, Republic Act No. 411 otherwise known as the Municipal Libraries Law, authored by then Senator Geronimo T. Pecson, which is an act to “provide for the establishment, operation and Maintenance of Municipal Libraries throughout the Philippines” was approved. Mrs. Felicidad A. Peralta 1948-1978 First City Librarian Side by side with the physical and economic development of Quezon City officials particularly the late Mayor Bernardo envisioned the needs of the people. Realizing that the achievements of the goals of a democratic society depends greatly on enlightened and educated citizenry, the Quezon City Public Library, was formally organized and was inaugurated on August 16, 1948, with Aurora Quezon, as a guest of Honor and who cut the ceremonial ribbon. The Library started with 4, 000 volumes of books donated by the National Library, with only four employees to serve the public. The library was housed next to the Post Office in a one-storey building near of the old City Hall in Edsa. Even at the start, this unit depended on the civic spirited members of the community who donated books, bookshelves and other reading material. -

Proceeding 2018

PROCEEDING 2018 CO OCTOBER 13, 2018 SAT 8:00AM – 5:30PM QUEZON CITY EXPERIENCE, QUEZON MEMORIAL, Q.C. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Tabassam Raza, MAURP, DBA, Ph.D. P.E. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EDITOR Ernie M. Lopez, MBA Ramon Iñigo M. Espinosa, AA MANAGING EDITOR EDITORIAL BOARD Jose F. Peralta, DBA, CPA PRESIDENT, CHIEF ACADEMIC OFFICER & DEAN Antonio M. Magtalas, MBA, CPA VICE PRESIDENT FOR FINANCE & TREASURER Tabassam Raza, MAURP, DBA, Ph.D. P.E. ASSOCIATE DEAN Jose Teodorico V. Molina, LLM, DCI, CPA CHAIR, GSB AD HOC COMMITTEE EDITORIAL STAFF Ernie M. Lopez Susan S. Cruz Ramon Iñigo M. Espinosa Philip Angelo Pandan The PSBA THIRD INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH COLLOQUIUM PROCEEDINGS is an official business publication of the Graduate School of Business of the Philippine School of Business Administration – Manila. It is intended to keep the graduate students well-informed about the latest concepts and trends in business, management and general information with the goal of attaining relevance and academic excellence. PSBA Manila 3IRC Proceedings Volume III October 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description Page Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. i Concept Note ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Program of Activities .......................................................................................................................... 6 Resource -

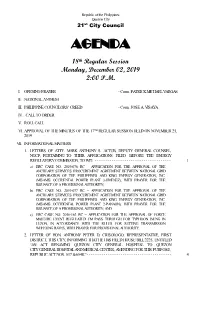

AGENDA (18Th Regular Session)

Republic of the Philippines Quezon City 21st City Council AGENDA 18th Regular Session Monday, December 02, 2019 2:00 P.M. I. OPENING PRAYER - Coun. PATRICK MICHAEL VARGAS II. NATIONAL ANTHEM III. PHILIPPINE COUNCILORS’ CREED - Coun. JOSE A. VISAYA IV. CALL TO ORDER V. ROLL CALL VI. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES OF THE 17TH REGULAR SESSION HELD ON NOVEMBER 25, 2019. VII. INFORMATIONAL MATTERS 1. LETTERS OF ATTY. MARK ANTHONY S. ACTUB, DEPUTY GENERAL COUNSEL, NGCP, PERTAINING TO THEIR APPLICATIONS FILED BEFORE THE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION, TO WIT: - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 a) ERC CASE NO. 2019-076 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF THE ANCILLARY SERVICES PROCUREMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN NATIONAL GRID CORPORATION OF THE PHILIPPINES AND KING ENERGY GENERATION, INC. (MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL POWER PLANT 3-JIMENEZ), WITH PRAYER FOR THE ISSUANCE OF A PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY; b) ERC CASE NO. 2019-077 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF THE ANCILLARY SERVICES PROCUREMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN NATIONAL GRID CORPORATION OF THE PHILIPPINES AND KING ENERGY GENERATION, INC. (MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL POWER PLANT 2-PANAON), WITH PRAYER FOR THE ISSUANCE OF A PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY; AND c) ERC CASE NO. 2016-163 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF FORCE MAJEURE EVENT REGULATED FM PASS THROUGH FOR TYPHOON INENG IN LUZON, IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE RULES FOR SETTING TRANSMISSION WHEELING RATES, WITH PRAYER FOR PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY. 2. LETTER OF HON. ANTHONY PETER D. CRISOLOGO, REPRESENTATIVE, FIRST DISTRICT, THIS CITY, INFORMING THAT HE HAS FILED HOUSE BILL 2225, ENTITLED “AN ACT RENAMING QUEZON CITY GENERAL HOSPITAL TO QUEZON CITY GENERAL HOSPITAL AND MEDICAL CENTER, AMENDING FOR THIS PURPOSE, REPUBLIC ACT NOS. -

CHAPTER 1: the Envisioned City of Quezon

CHAPTER 1: The Envisioned City of Quezon 1.1 THE ENVISIONED CITY OF QUEZON Quezon City was conceived in a vision of a man incomparable - the late President Manuel Luis Quezon – who dreamt of a central place that will house the country’s highest governing body and will provide low-cost and decent housing for the less privileged sector of the society. He envisioned the growth and development of a city where the common man can live with dignity “I dream of a capital city that, politically shall be the seat of the national government; aesthetically the showplace of the nation--- a place that thousands of people will come and visit as the epitome of culture and spirit of the country; socially a dignified concentration of human life, aspirations and endeavors and achievements; and economically as a productive, self-contained community.” --- President Manuel L. Quezon Equally inspired by this noble quest for a new metropolis, the National Assembly moved for the creation of this new city. The first bill was filed by Assemblyman Ramon P. Mitra with the new city proposed to be named as “Balintawak City”. The proposed name was later amended on the motion of Assemblymen Narciso Ramos and Eugenio Perez, both of Pangasinan to “Quezon City”. 1.2 THE CREATION OF QUEZON CITY On September 28, 1939 the National Assembly approved Bill No. 1206 as Commonwealth Act No. 502, otherwise known as the Charter of Quezon City. Signed by President Quezon on October 12, 1939, the law defined the boundaries of the city and gave it an area of 7,000 hectares carved out of the towns of Caloocan, San Juan, Marikina, Pasig, and Mandaluyong, all in Rizal Province. -

Filipino Star July 2012 Issue

Vol. XXX, No. 7 JULY 2012 http://www.filipinostar.org It's fiesta time for Filipinos in Montreal and suburbs. By W. G. Quiambao Mackenzie King park was chock-full of activities last July 15 during the FAMAS Pista sa Nayon, one of the much-anticipated events by many Filipinos in Montreal and suburbs. Friends seeing friends they haven’t seen for a while, music lovers listening to Filipino songs, women playing volleyball, kids enjoying pabitin (a rack of items is suspended over a crowd who attempt to grab at the stuff as the wooden rack is lowered and raised several times until everything is gone), revellers enjoying A few games of volleyball, arranged and managed by Mercy Sia Umipig and played by all-girl teams, was part of Pista sa Nayon (Photo: B. Sarmiento) a bounty of delicious foods - these are some of the activities during Pista sa Part of Ambassador Leslie B. bond of unity in a foreign setting." Nayon in the Philippines which are also Gatan's message read, "I wish to The tradition of the Pista sa practiced in Montreal every year. extend my heartfelt and warm Nayon dates back to centuries to the “Today, we celebrate the very congratulations to the Officers and rural areas and town in the Philippines. best of being Filipino," said Au Osdon, members of the Filipino Association of During Pista sa Nayon (called town FAMAS president. "The Bayanihan Montreal & Suburbs for their festival or fiesta), Filipinos would gather spirit is manifested by the support, sponsorship of the annual Pista sa for a fiesta in the middle of town to participation and involvement of so Nayon (town fiesta) with the main celebrate a good harvest. -

REGIONAL DIRECTOR's CORNER January 2020

Republic of the Philippines Office of the President PHILIPPINE DRUG ENFORCEMENT AGENCY REGIONAL OFFICE-NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION PDEA Annex Bldg., NIA Northside Road, National Government Center, Barangay Pinyahan, 1100 Quezon City/Telefax:(02)8351-7433/e-mail address:[email protected]/[email protected] pdea.gov.ph PDEA Top Stories PDEA@PdeaTopStories pdeatopstories REGIONAL DIRECTOR’S CORNER January 2020 On January 6, 2020, Director III JOEL B PLAZA Regional Director of PDEA RO- NCR, together with IA V Mary Lyd Arguelles, QC District Officer and other members of QCDO attended the Quezon City Peace and Order Council Conference held at 15th floor high rise Building, Quezon City Hall. The conference was attended by Hon. Ma. Josefina Belmonte, Quezon City Mayor, City Administrator Michael Alimurung, Mr. Ricardo Belmonte, Secretary to the Mayor, PBGen. Ronnie Montejo, QCPD Director, Director Rufino Mendoza, Director, NICA, JTF NCR and DILG. On January 24, 2020, Director III JOEL B PLAZA Regional Director of PDEA RO- NCR, together with IA I Berlin Orlanes of Intelligence Division attended conference meeting re Rubita Gracia Murder Case held at the Philippine Cancer Society Bldg., 310 San Rafael Street, Malacanang Complex, City of Manila. The conference was presided by USEC Jose Joel M Sy Egco. On January 28, 2020 Director III JOEL B PLAZA Regional Director of PDEA RO-NCR led the conduct of Regional Oversight Committee on Barangay Drug Clearing Program for the clearing and declaration of the forty (40) applicant barangays that are considered as drug affected from the 6 cities throughout Metro Manila on Tuesday, held at the PDEA Main Conference Room, Brgy. -

LGU Best Practices

1 Page 1-19 (Intro) 1 1/5/06, 5:50 PM 2 Page 1-19 (Intro) 2 1/5/06, 5:50 PM LOCAL GOVERNMENT FISCAL and FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT Best Practices Juanita D. Amatong Editor 3 Page 1-19 (Intro) 3 1/5/06, 5:50 PM Local Government Fiscal and Financial Management Best Practices Juanita D. Amatong, Editor Copyright © Department of Finance, 2005 DOF Bldg., BSP Complex, Roxas Blvd. 1004 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel: + 632 404-1774 or 76 Fax: + 632 521-9495 Web: http://www.dof.gov.ph Email: [email protected] First Printing, 2005. Cover design by Hoche M. Briones Photos by local governments of Santa Rosa, Malalag, San Jose de Buenavista, Quezon City, Gingoog City, and Rashel Yasmin Z. Pardo (Province of Bohol) and Niño Raymond B. Alvina (Province of Aklan). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without express permission of the copyright owners and the publisher. ISBN 971-93448-0-6 Printed in the Philippines. 4 Page 1-19 (Intro) 4 1/5/06, 5:50 PM CONTENTS About the Project ................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements ................................................................................. 9 Message ................................................................................................ 11 Foreword .............................................................................................. 12 Introduction ......................................................................................... 15 Revenue Generation Charging -

Central Banking in the Philippines: Then, Now and the Future (Mario B

The author is the President of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS). He received his Ph.D. in Economics from the University of the Philippines School of Economics (UPSE) and pursued his post-doctoral studies at the Stanford University. He specializes in money and banking, international finance and development economics. This paper was prepared for the Perspective Paper Symposium Series and presented on 22 August 2002 as part of the Institute’s celebration of its 25th anniversary. The author thanks his colleagues at the Institute, and Cyd Tuaño- Amador and Diwa Guinigundo of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas for their insightful comments on the first draft of this paper. He also thanks Juanita E. Tolentino and Jose Maria B. Ruiz for their excellent research assistance. Then, Now,and the Future Mario B. Lamberte PERSPECTIVEPAPER SERIES No.5 PHILIPPINEINSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENTSTUDIES Surian sa mg-dPag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Copyright 2003 Philippine Institute for DevelopmentStudies Printed in the Philippines. All rights reserved. The views expressedin this paper are those of the author and do not necessarilyreflect the views of any individual or organization. Please do not quote without permission from the author nor PIDS. Pleaseaddress all inquiries to: Philippine Institute for Development Studies NEDA sa Makati Building, 106Amorsolo Street Legaspi Village, 1229 Makati City, Philippines Tel: (63-2) 893-5705 / 892-4059 Fax: (63-2) 893-9589/816-1091 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.pids.gov.ph ISBN 971-564-068-0 RP 12-03-500 Foreword The Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PillS) celebrated its silver founding anniversary in 2002. -

Lloydluna 2010-Cv

Lloyd A. Luna Business Evangelist 1745 Dian St. Palanan Village Makati City, NCR 1235 Philippines Summary of Qualification T (63) 2 5055336 Motivational speaker in Asia; Probably the youngest M (63) 927 7562777 [email protected] speaker to speak in major conventions in Malaysia, www.lloydluna.com Brunei, Vietnam, Thailand, and South Korea. Spoken to more than half a million people in the last five years; Author of 8 books including the bestsellers Is There A Job Waiting For You?, The Obvious, The Internet Marketing Handbook, and Why Am I Working?; Television Host of the Philippines’ Most Dynamic Business Talk Show; Business advisor with expertise in sales and marketing, workplace motivation, operations, leadership, and change; Corporate trainer to local and multinational corporations in the Philippines and Asia; Speechwriter to business leaders and political figures; Columnist at The Manila Times, Kabayan Star (Hong Kong), GoodNewsPilipinas (Singapore), and Planet Philippines (Canada) among other news organizations; Political advisor; Resource expert on Television, radio, and the Internet on career- and business-related issues; Resource speaker on conferences and corporate events Asia-wide. Media Appearances (also in Youtube.com/lloydluna) Television (ABS-CBN and The Filipino Channel) Rated K hosted by Korina Sanchez, The 25th Anniversary Special, Four Successful Filipinos at age 25 (ABS-CBN) Kabuhayang Swak na Swak hosted by Amy Perez, Business in Speaking and Writing Books (QTV Ch. 11) Ang Pinaka (The Most), Are You In A Wrong Job? (QTV Ch. 11) The 700 Club Asia, Characters Needed to Succeed 1 (TV5) E-Connect with Earl Beja, What is success? (GNN Ch. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Financial Highlights 4 Message of the Chairman 6 Financial Review 8 A Kapamilya Nation 16 Management’s Responsibility for Financial Statements 17 Report of Independent Auditors 18 Financial Statements Balance Sheets Statements of Income Statements of Changes in Stockholders’ Equity Statements of Cash Flows Notes to Financial Statements 68 Board of Directors 70 Management Committee 72 Awards and Recognition 73 List of Officers 77 Corporate Addresses 79 Banks and Other Financial Institutions AR 2006.indd 1 4/24/07 8:10:44 AM FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS AR 2006.indd 2-3 4/24/07 8:10:49 AM AR 2006.indd 4-5 4/24/07 8:11:09 AM Operating expenses, which consist of production cost, general and administrative Non-cash operating expenses, composed primarily of depreciation and expenses, cost of sales and services, and agency commission declined by 2% amortization, went down by 14% to P2,075 million in 2006 from P2,407 million to P15,724 million in 2006. Cash operating expenses were flat while non-cash in the same period last year. Bulk of the decline can be attributed to lower operating expenses declined by 14% YoY. If we strip-out the non-recurring charges, amortization costs which dropped by 23% to P904 million as the Company already Management Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of total opex went up by 5% to P15,257 million. completed the amortization of deferred subsidies on the decoder boxes of existing Operations for 2006 US DTH subscribers in 2005. Amortization of program rights, on the other hand, Production cost was almost flat YoY at P5,714 million. -

Clean Elections and the Great Unwashed Vote Buying and Voter Education in the Philippines

Clean Elections and the Great Unwashed Vote Buying and Voter Education in the Philippines Frederic Charles Schaffer APRIL 2005, PAPER NUMBER 21 ©Unpublished by Frederic Charles Schaffer The Occasional Papers of the School of Social Science are versions of talks given at the School’s weekly Thursday Seminar. At these seminars, Members present work-in-progress and then take questions. There is often lively conversation and debate, some of which will be included with the papers. We have chosen papers we thought would be of interest to a broad audience. Our aim is to capture some part of the cross-disciplinary conversations that are the mark of the School’s programs. While members are drawn from specific disciplines of the social sciences—anthropology, economics, sociology and political science—as well as history, philosophy, literature and law, the School encourages new approaches that arise from exposure to different forms of interpretation. The papers in this series differ widely in their topics, methods, and disciplines. Yet they concur in a broadly humanistic attempt to under- stand how, and under what conditions, the concepts that order experience in different cultures and societies are produced, and how they change. Frederic Schaffer is Research Associate at the Center for International Studies at M. I. T. He was a Member in the year 2003-04, when the School’s focus had turned to bio-medical ethics. But Schaffer’s work harkened back to questions of corruption. His research focuses primarily on the impact of local cultures on the operation of electoral institutions, with a geographic focus on Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. -

State Violence in the Philippines

State violence in the Philippines An alternative report to the United Nations Human Rights Committee presented by People's Recovery, Empowerment and Development Assistance Foundation, Inc. A project coordinated by World Organisation Against Torture Case postale 21- 8, rue du Vieux Billard CH-1211 Geneva 8, Switzerland Geneva, September 2003 Foreword Writing alternative reports is one of the main activities of the OMCT and a vital source of information for the members of the Human Rights Committee. With these reports, it is possible to see the situation as objectively as possible and take a critical look at government action to eradicate torture. Under the aegis of the European Union and the Swiss Confederation, the “Special Procedures” program presented this report on state violence and torture in the Philippines at the 79th session of the Human rights Committee, which took place in Geneva from 20th October to 7th November 2003 and during which the Government’s report of the Philippines was examined. The study is divided into three parts. Part I provides a general overview of torture and inhuman or degrading treatments (in prisons in particular) committed by state officials. Parts II and III deal with torture and inhuman or degrading treatments of women and children respectively. This rather novel approach sheds light on the situation of particularly vulnerable groups of people. The Human Rights Committee’s Concluding Observations and Recommendations adopted following examination of the Filipino Government’s Report are included in the Appendices. This report was jointly prepared by the following three Filipino human rights NGOs: PREDA Foundation. Nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001, Preda Foundation, Inc., was founded in 1974 in Olongapo City.