Erik Satie's Socrate (1918), Myths of Marsyas, and Un Style Dépouillé

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Trial and Death of Socrates : Being the Euthyphron, Apology, Crito, and Phaedo of Plato

LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO /?. (Boffcen THE TRIAL & DEATH OF SOCRATES *O 5' dve^Tcurroj /3toj ov /Siwrds cu>0p(j!nrip ' An unexamined life is not worth living.' (PLATO, Apol. 38 A. ) THE TRIAL AND DEATH OF SOCRATES BEING THE EUTHYPHRON, APOLOGY, CRITO, AND PH^EDO OF PLATO TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY F. J. CHURCH, M.A. LONDON MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1895 [ All rights reserved.] First Edition printed 1880 Second Edition, Golden Treasury Series, 1886 Reprinted 1887, 1888, 1890, 1891, 1892, March and September 1895 PREFACE. THIS book, which is intended principally for the large and increasing class of readers who wish to learn something of the masterpieces of Greek literature, and who cannot easily read them in Greek, was originally published by Messrs. Macmillan in a different form. Since its first appearance it has been revised and corrected throughout, and largely re- written. The chief part of the Introduction is new. It is not intended to be a general essay on Socrates, but only an attempt to explain and illustrate such points in his life and teaching as are referred to in these dialogues, which, taken by themselves, con- tain Plato's description of his great master's life, and work, and death. The books which were most useful to me in writing it are Professor Zeller's Socrates and the Socratic Schools, and the edition of the VI PREFACE. Apology by the late Rev. James Riddell, published after his death by the delegates of the Clarendon Press. His account of Socrates is singularly striking. -

The Poverty of Socratic Questioning: Asking and Answering in the Meno

University of Cincinnati University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications Faculty Articles and Other Publications College of Law Faculty Scholarship 1994 The oP verty of Socratic Questioning: Asking and Answering In The eM no Thomas D. Eisele University of Cincinnati College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.uc.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Eisele, Thomas D., "The oP verty of Socratic Questioning: Asking and Answering In The eM no" (1994). Faculty Articles and Other Publications. Paper 36. http://scholarship.law.uc.edu/fac_pubs/36 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law Faculty Scholarship at University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles and Other Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POVERTY OF SOCRATIC QUESTIONING: ASKING AND ANSWERING IN THE MEND Thomas D. Eisele* I understand [philosophy 1 as a willingness to think not about some thing other than what ordinary human beings think about, but rather to learn to think undistractedly about things that ordinary human beings cannot help thinking about, or anyway cannot help having occur to them, sometimes in fantasy, sometimes asa flash across a landscape; such things, for example, as whether we can know the world as it is in itself, or whether others really know the nature of one's own experiences, or whether good and bad are relative, or whether we might not now be dreaming that we are awake, or whether modern tyrannies and weapons and spaces and speeds and art are continuous with the past of the human race or discontinuous, and hence whether the learning of the human race is not irrelevant to the problems it has brought before itself. -

The Historicity of Plato's Apology of Socrates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1946 The Historicity of Plato's Apology of Socrates David J. Bowman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Bowman, David J., "The Historicity of Plato's Apology of Socrates" (1946). Master's Theses. 61. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/61 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1946 David J. Bowman !HE HISTORICITY OP PLATO'S APOLOGY OF SOCRATES BY DA.VID J. BOWJWf~ S.J• .l. !BESIS SUBMITTED Ilf PARTIAL FULFILIJIE.NT OF THB: R}gQUIRE'IIENTS POR THE DEGREE OF IIA.STER OF ARTS Ill LOYOLA UlfiVERSITY JULY 1946 -VI'fA. David J. Bowman; S.J•• was born in Oak Park, Ill1no1a, on Ma7 20, 1919. Atter b!a eleaentar7 education at Ascension School# in Oak Park, he attended LoJola AcademJ ot Chicago, graduat1DS .from. there in June, 1937. On September 1, 1937# he entered the Sacred Heart Novitiate ot the SocietJ ot Jesus at Milford~ Ohio. Por the tour Jear• he spent there, he was aoademicallJ connected with Xavier Univeraitr, Cincinnati, Ohio. In August ot 1941 he tranaterred to West Baden College o.f Lorol& Universit7, Obicago, and received the degree ot Bachelor o.f Arts with a major in Greek in Deo.aber, 1941. -

The Prosecutors of Socrates and the Political Motive Theory

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2-1981 The prosecutors of Socrates and the political motive theory Thomas Patrick Kelly Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Intellectual History Commons, and the Political History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kelly, Thomas Patrick, "The prosecutors of Socrates and the political motive theory" (1981). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2692. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2689 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Thomas Patrick Kelly for the Master of Arts in History presented February 26, 1981. Title: The Prosecutors of Socrates and The Political Motive Theory. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS CO~rnITTEE: ~~varnos, Cha1rman Charles A. Le Guin Roderlc D1man This thesis presents a critical analysis of the histor- ical roles assigned to the prosecutors of Socrates by modern historians. Ancient sources relating to the trial and the principles involved, and modern renditions, especially those of John Burnet and A. E. Taylor, originators of the theory that the trial of Socrates was politically motivated, are critically 2 analyzed and examined. The thesis concludes that the political motive theory is not supported by the evidence on which it relies. THE PROSECUTORS OF SOCRATES AND THE POLITICAL MOTIVE THEORY by THOMAS PATRICK KELLY A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY Portland State University 1981 TO THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH: The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Thomas Patrick Kelly presented February 26, 1981. -

The Cult of Socrates: the Philosopher and His Companions in Satie's Socrate

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program Spring 2013 The Cult of Socrates: The Philosopher and His Companions in Satie's Socrate Andrea Decker Moreno Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Moreno, Andrea Decker, "The Cult of Socrates: The Philosopher and His Companions in Satie's Socrate" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 145. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/145 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CULT OF SOCRATES: THE PHILOSOPHER AND HIS COMPANIONS IN SATIE’S SOCRATE by Andrea Decker Moreno Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of HONORS IN UNIVERSITY STUDIES WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS in Music – Vocal Performance in the Department of Music Approved: Thesis/Project Advisor Departmental Honors Advisor Dr. Cindy Dewey Dr. Nicholas Morrison Director of Honors Program Dr. Nicholas Morrison UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT Spring 2013 The Cult of Socrates: The philosopher and his companions in Satie's Socrate Satie's Socrate is an enigma in the musical world, a piece that defies traditional forms and styles. Satie chose for his subject one of the most revered characters of history, the philosopher Socrates. Instead of evaluating his philosophy and ideas, Satie created a portrait of Socrates from the most intimate moments Socrates spent with his followers in Plato's dialogues. -

The Italian Academies and Rabbi Simone Luzzatto's Socrate

Michela Torbidoni The Italian Academies and Rabbi Simone Luzzatto’s Socrate:the Freedom of the Ingenium and the Soul 1Introduction Simone Luzzatto, chief rabbi of the Jewish community of Venice, ahighlytalented classicistconversant with Latin and Greek literature as well as apassionate reader of medievalItalian culture, wasthe author of the well-known apologetic treatise Dis- corso circa il stato degli Hebrei et in particular dimoranti nell’inclita città di Venetia (‘Discourse Concerningthe Condition of the Jews, and in Particular Those Living in the Fair City of Venice’), publishedinVenice in 1638, and also of Socrate overo dell’humano sapere (‘Socrates or on Human Knowledge’), which appearedinVenice in 1651.The scope and purpose of this latter work are indicated in the book’sextend- ed title: Esercitio seriogiocoso di Simone Luzzatto hebreo venetiano.Operanellaquale si dimostraquanto sia imbecilel’humano intendimento,mentre non èdiretto dalla div- ina rivelatione (‘The Serious-Playful Exercise of Simone Luzzatto, Venetian Jew. A Book That ShowsHow Incapable Human IntelligenceCan Be When It Is Not Led by DivineRevelation’). Thus, the work is meantasademonstration of the limits and weaknesses of the human capacity to acquire knowledge without being guided by revelation. Luzzatto achievedthis goal by offering an overviewofthe various and contradictory gnosiological opinions disseminated since ancient times: he analyses the human faculties, namely the functioningofthe external (five)senses, the internal senses (common sense, imagination, memory,and the estimative faculty), the intel- lect,and alsotheir mutualrelation.¹ In his work, Luzzatto gave an accurate analysis of all these issues by getting to the heart of the ancientepistemological theories. The divergence of views, to which he addressed the most attention, prevented him from giving afixed definition of the nature of the cognitive process. -

SATIE Gymnopédies

1000 YEARS OF CLASSICAL MUSIC SATIE Gymnopédies VOLUME 74 | THE MODERN ERA FAST FACTS • Erik Satie is famous for his deeply eccentric nature, which extended to his dress (at one point he bought seven identical velvet suits and then, for more than ten years, wore nothing else), his eating habits (he claimed to eat only white food: ‘eggs, sugar, shredded bones, the fat of dead animals, veal, salt, coconuts, SATIE chicken cooked in white water, mouldy fruit, rice, turnips, sausages in camphor, pastry, cheese (white Gymnopédies varieties), cotton salad, and certain kinds of fish, without their skin’), and the instructions he gave to those performing his music: his scores are full of enigmatic notes such as ‘Light as an egg’, ‘Open your head’, ERIK SATIE 1866–1925 ‘Work it out yourself’ and ‘Don’t eat too much’. Trois Gymnopédies [9’44] 1 No. 1: Lent et douloureux (Slow and full of suffering) 3’37 • His sharp wit, irreverence and refusal to do as expected led him to reject the big, lush Romantic 2 No. 2: Lent et triste (Slow and sad) 3’06 tradition of composers like Wagner, and turn instead to shorter, simpler pieces in which melody was 3 No. 3: Lent et grave (Slow and solemn) 2’54 the central element. 4 Je te veux (I Want You) 5’17 • Satie broke new ground in many different musical ways. His familiarity with the world of cabaret (he [7’16] Trois Gnossiennes supported himself for several years by working as a pianist at Le Chat Noir and other Montmartre 5 No. -

Mauro Tulli / Michael Erler (Eds.) Plato in Symposium

Mauro Tulli / Michael Erler (eds.) Plato in Symposium International Plato Studies Published under the auspices of the International Plato Society Series Editors: Franco Ferrari (Salerno), Lesley Brown (Oxford), Marcelo Boeri (Santiago de Chile), Filip Karfik (Fribourg), Dimitri El Murr (Paris) Volume 35 PLATO IN SYMPOSIUM SELECTED PAPERS FROM THE TENTH SYMPOSIUM PLATONICUM Edited by MAURO TULLI AND MICHAEL ERLER Academia Verlag Sankt Augustin Illustration on the cover by courtesy of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Ashmole 304, fol. 31 v. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. ISBN: 978-3-89665-678-0 1. Auflage 2016 © Academia Verlag Bahnstraße 7, D-53757 Sankt Augustin Internet: www.academia-verlag.de E-Mail: [email protected] Printed in Germany Alle Rechte vorbehalten Ohne schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages ist es nicht gestattet, das Werk unter Verwendung mechanischer, elektronischer und anderer Systeme in irgendeiner Weise zu verarbeiten und zu verbreiten. Insbesondere vorbehalten sind die Rechte der Vervielfältigung – auch von Teilen des Werkes – auf fotomechanischem oder ähnlichem Wege, der tontechnischen Wiedergabe, des Vortrags, der Funk- und Fernsehsendung, der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlagen, der Übersetzung und der literarischen und anderweitigen Bearbeitung. List of contributors Olga Alieva, National -

Vladimir Mendelssohn, Alto Dorel Fodoreanu, Violoncelle Lidija Bizjak, Piano Leonard Bernstein West Side Story Version Pour 2 Pianos

Palazzo Contarini Polignac Week-end Musical 11 - 12 novembre 2017, Venise En hommage à Winnaretta Singer Princesse Edmond de Polignac 1865 - 1943 “The Only Winnie in the World...” (Gabriel Fauré, in a letter to Winnaretta written shortly before his death.) As we enjoy this year’s splendid November program at the Palazzo Contarini Polignac, it seems appropriate to recall Winnaretta’s life here in Venice, and her personal recollections of some of the composers whose work we shall hear this weekend. I felt, though, that it might be entertaining to begin with a recollection of Winnaretta herself, by her friend Sir Ronald Storrs, a British Foreign and Colonial Office official who was a regular guest here in Venice in the years preceding the First World War: “During a summer holiday I met for the first time Princess Edmond de Polignac. This Les Amis de Winnaretta Singer lady, daughter of the Singer who I suppose has eased the life of the seamstress and the housewife more than any other public benefactor, maintained a cottage in Surrey, a house in Chelsea, a L’association « Les Amis de Winnaretta Singer » a été créée en 2015 à Paris par Henri- hôtel in Paris, a palace in Venice; and, using her wealth with a wise and appreciative artistry, led (and continues to lead) a life resembling in many ways that of a great Renaissance princess. She François de Breteuil et Daniel Popesco, avec le concours de la famille de la Princesse painted pictures that were later sold, without her knowledge, as undoubted Manets; she played Edmond de Polignac. -

Table of Contents Is Interactive

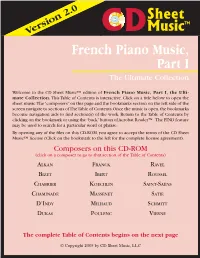

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 French Piano Music, Part I The Ultimate Collection Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of French Piano Music, Part I, the Ulti- mate Collection. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “composers” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navigate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Composers on this CD-ROM (click on a composer to go to that section of the Table of Contents) ALKAN FRANCK RAVEL BIZET IBERT ROUSSEL CHABRIER KOECHLIN SAINT-SAËNS CHAMINADE MASSENET SATIE D’INDY MILHAUD SCHMITT DUKAS POULENC VIERNE The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 VALENTIN ALKAN IV. La Bohémienne Saltarelle, Op. 23 V. Les Confidences Prélude in B Major, from 25 Préludes, VI. Le Retour Op. 31, No. 3 Variations Chromatiques de concert Symphony, from 12 Études Nocturne in D Major I. Allegro, Op. 39, No. -

Nicolas Horvath Erik Satie (1866-1925) Intégrale De La Musique Pour Piano • 3 Nouvelle Édition Salabert

comprenant DES PREMIERS ENREGISTREMENTS MONDIAUX SATIE INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH, Piano Numéro de catalogue : GP763 Date d’enregistrement : 11 décembre 2014 Lieu d’enregistrement : Villa Bossi, Bodio, Italie Publishers: Durand/Salabert/Eschig 2016 Edition Piano : Érard de Cosima Wagner, modèle 55613, année 1881 Producteur et Éditeur : Alexis Guerbas (Les Rouages) Ingénieur du son : Ermanno De Stefani Rédaction du livret : Robert Orledge Traduction française : Nicolas Horvath Photographies de l’artiste : Laszlo Horvath Portrait du compositeur : Santiago Rusiñol Una romanza ©MNAC Couverture : Sigrid Osa L’artiste tient à remercier sincèrement Ornella Volta et la Fondation Erik Satie. 2 1 PRÉLUDE DU NAZARÉEN [EN DEUX PARTIES] ** 10:23 uspud – ballet chrétien en trois actes ** 23:53 2 Acte 1 09:33 3 Acte 2 06:20 4 Acte 3 07:53 5 EGINHARD. PRÉLUDE 02:04 6 DANSES GOTHIQUES ** 10:34 7 VEXATIONS 07:01 8 SANS TITRE, PEUT-ÊTRE POUR LA MESSE DES PAUVRES, [MODÉRÉ] 01:04 9 PRÉLUDE DE « LA PORTE HÉROÏQUE DU CIEL » ** 04:50 0 GNOSSIENNE [N° 6] 02:17 ! SANS TITRE, ?GNOSSIENNE [PETITE OUVERTURE À DANSER] ** 02:09 PIÈCES FROIDES : AIRS À FAIRE FUIR 10:00 @ D’une manière très particulière 04:30 # Modestement 01:09 $ S’inviter ** 04:19 % AIRS À FAIRE FUIR N° 2 (version plus chromatique) * 00:26 PIÈCES FROIDES : DANSES DE TRAVERS ** 06:25 ^ En y regardant à deux fois 02:02 & Passer 01:44 * Encore 02:37 ( DANSE DE TRAVERS II ** 03:12 * PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DURÉE TOTALE: 85:03 ** PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DE LA VERSION RÉVISÉE PAR ROBERT ORLEDGE 3 ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT À PROPOS DE NICOLAS HORVATH ET DE LA NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT DES « ŒUVRES POUR PIANO » DE SATIE. -

Poulenc, Francis (1899-1963) by Mario Champagne

Poulenc, Francis (1899-1963) by Mario Champagne Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Francis Poulenc with harpsichordist Wanda Landowska. One of the first openly gay composers, Francis Poulenc wrote concerti, chamber music, choral and vocal works, and operas. His diverse compositions are characterized by bright colors, strong rhythms, and novel harmonies. Although his early music is light, he ultimately became one of the most thoughtful composers of serious music in the twentieth century. Poulenc was born on January 7, 1899 into a well-off Parisian family. His father, a devout Roman Catholic, directed the pharmaceutical company that became Rhône-Poulenc; his mother, a free-thinker, was a talented amateur pianist. He began studying the piano at five and was following a promising path leading to admission to the Conservatoire that was cut short by the untimely death of his parents. Although he did not attend the Conservatoire he did study music and composition privately. At the death of his parents, Poulenc inherited Noizay, a country estate near his grandparents' home, which would be an important retreat for him as he gained fame. It was also the source of several men in his life, including his second lover, the bisexual Raymond Destouches, a chauffeur who was the dedicatee of the surrealistic opera Les mamelles de Tirésias (1944) and the World War II Resistance cantata La figure humaine (1943). From 1914 to 1917, Poulenc studied with the Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes, through whom he met other musicians, especially Georges Auric, Erik Satie, and Manuel de Falla.