Great Museums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saint Demetrios of Thessaloniki

Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow Saint Demetrios of Thessaloniki By Lena Kousouros Christie's Education London Master's Programme September 2000 ProQuest Number: 13818861 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818861 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ^ v r r ARV- ^ [2,5 2 . 0 A b stract This thesis intends to explore the various forms the representations of Saint Demetrios took, in Thessaloniki and throughout Byzantium. The study of the image of Saint Demetrios is an endeavour of considerable length, consisting of numerous aspects. A constant issue running throughout the body of the project is the function of Saint Demetrios as patron Saint of Thessaloniki and his ever present protective image. The first paper of the thesis will focus on the transformation of the Saint’s image from courtly figure to military warrior. Links between the main text concerning Saint Demetrios, The Miracles, and the artefacts will be made and the transformation of his image will be observed on a multitude of media. -

The Ethics of the International Display of Fashion in the Museum, 49 Case W

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 49 | Issue 1 2017 The thicE s of the International Display of Fashion in the Museum Felicia Caponigri Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Felicia Caponigri, The Ethics of the International Display of Fashion in the Museum, 49 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 135 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol49/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 49(2017) THE ETHICS OF THE INTERNATIONAL DISPLAY OF FASHION IN THE MUSEUM Felicia Caponigri* CONTENTS I. Introduction................................................................................135 II. Fashion as Cultural Heritage...................................................138 III. The International Council of Museums and its Code of Ethics .....................................................................................144 A. The International Council of Museums’ Code of Ethics provides general principles of international law...........................................146 B. The standard that when there is a conflict of interest between the museum and an individual, the interests of the museum should prevail seems likely to become a rule of customary international law .................................................................................................149 IV. China: Through the Looking Glass at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.......................................................................162 A. Anna Wintour and Condé Nast: A broad museum interest for trustees and a semi-broad museum interest for sponsors .................164 B. -

Student Tours

STUDENT T OUR S BOSTON NEW YORK CITY PHILADELPHIA WASHINGTON, D.C. LOCAL DESTINATIONS HISTORICAL SITES MUSEUMS & MORE! ® LOCAL DAY TRIPS CONNECTICUT CT Science Center Essex Steam Train and Riverboat Mark Twain House/Harriet Beecher Stowe House Seven Angels Theatre Mystic Aquarium Mystic Seaport Shubert Theatre - Educational Programs Wadsworth Athenium Mark Twain House, Hartford, CT MASSACHUSETTS Sturbridge Village Plimoth Patuxet Museum Salem Witch Museum NEWPORT, RI Self-guided Mansion Tours Servant Life Guided Tours Essex Steam Train, Essex, CT Fort Adams Tours NEW JERSEY Medieval Times Liberty Science Center American Dream Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, CT Salem Witch Museum, Salem, MA BOSTON Boston has it all for your group! Your DATTCO Tours representative will plan an exciting and interesting day, book all of the attraction visits, and provide you a detailed itinerary! Build your own tour with any of these attractions and more: Museums/Attractions Boston Tea Party Museum Be a part of the famous event that forever changed the course of American history with historical interpreters and interactive exhibits. Franklin Park Zoo John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum Faneuil Hall, Boston, MA Exhibits highlight the life, leadership & legacy of President Kennedy Mapparium at Mary Baker Eddy Library Enter a 30ft glass bridge into a stained glass globe that serves as a historic snapshot of the world as it existed in 1935. Museum of Science New England Aquarium Quincy Market/Faneuil Hall Duck Boat, Charles River, Boston, MA Tours Shows Boston Duck Tours Blue Man Group Fenway Park Tours Boston Ballet Freedom Trail Tour (Guided) Boston Pops Harvard/MIT Tours Boston Symphony Orchestra Whale Watch Tours Broadway Shows in Boston DINING OPTIONS Fire & Ice • Hard Rock Café • Maggiano’s Quincy Market Meal Vouchers • Boxed lunches are also available NEW YORK CITY Experiences Customized Private Tours Broadway Shows NYC Guided Tour Many shows offer special student rates. -

THE CLOISTERS ARCHIVES Collection No. 43 the Harry Bober

THE CLOISTERS ARCHIVES Collection No. 43 The Harry Bober Papers Processed 1995, 2013 The Cloisters Library The Metropolitan Museum of Art Ft. Tryon Park 99 Margaret Corbin Dr. New York, NY 10040 (212) 396-5365 [email protected] 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE…….…………………………………………..……………….….…………………2 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION…….……………….………….………………….……3 HARRY BOBER TIME LINE…….…………………………………………………….………4 HARRY BOBER BIBLIOGRAPHY…….…………………………………..…………….……5 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE…….………………………………………….………..……..8 SERIES DESCRIPTIONS…….………………………………………………………….…….10 CONTAINER LISTS Series I. Card Files…………….……………………………………………..……..13-30 Series II. Research Files………….……………………………………...…………31- 72 Series III. Publications ………….…………………………………………….…..73 Series IV. Slides………….……………………………………………..….………..74-77 Series V. Glass Plate Negatives………….…………………………………….………..78 Series VI. Negative Films………….………………………………………..………79-81 Series VII. Oversize Material………….……………………………….....……....…82-83 Series VIII. 1974 Messenger Lectures, Recordings (tapes and CDs) …………....…..…84 1 PREFACE In 1991, the papers of Harry Bober were donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by his sons, David and Jonathan Bober. The collection was delivered to the Medieval Department of the museum, where it was housed until its transfer to The Cloisters Archives during the summer of 1993. Funding for the first year of a two-year processing project was provided through the generosity of Shelby White and Leon Levy. The first year of the project to process the Harry Bober Papers began in August of 1994 and ended in August of 1995, conducted by Associate Archivist Elaine M. Stomber. Tasks completed within the first year included: rehousing the collection within appropriate archival folders and boxing systems; transferring original folder titles to new folders; conservation repair work to the deteriorating card file system; creating a container list to Bober's original filing system; transferring published material from research files; and preparing a preliminary finding aid to the collection. -

879-5500 Schedule of Exhibitions

The Metropolitan Museum of Art 82nd Street and Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10028 (212)879-5500 Schedule of Exhibitions - December 1982 NEW EXHIBITIONS Dec. 3 Opening of the Living Room from the Francis Little House (Permanent Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright installation) Installation of the living room from the house Frank Lloyd Wright designed for Francis Little in Wayzata, Minn., acquir ed by the Metropolitan when the house was torn down in 19 72. Room will be installed with much of its original furniture designed by Wright. The installation is made possible through the generosity of Saul P. Steinberg and Reliance Group Holdings, Inc. (In The American Wing) Dec. 3 (Through Feb. 27) Frank Lloyd Wright at the Metropolitan Museum An exhibition of about 100 objects from the Museum's collec tion of Frank Lloyd Wright material: architectural drawings, furniture, antique photographs, ceramics, engravings, fragments and graphics. Exhibition is made possible through the generos ity of Saul P. Steinberg and Reliance Group Holdings, Inc. (In The American Wing; galleries adjacent to Francis Little Eoom installation) Dec. 3 Installation of the Museum's Annual Christmas Tree and Baroque (Through Jan. 9) Creche Display Nineteenth consecutive annual display of the Museum's famous Christmas tree and collection of 200 18th-century Baroque Neapolitan creche figures presented to the Museum by Loretta Hines Howard in 1964. The installation is made possible by Reliance Group Holdings, Inc. (In the Medieval Sculpture Court, main floor) Dec. 7 Annual Christmas Display at The Cloisters (Through Jan. 9) At Christmas each year the whole of The Cloisters becomes suffused with holiday fragrances, flowers, candlelight and music. -

Painted Wood: History and Conservation

PART FOUR Investigations and Treatment 278 Monochromy, Polychromy, and Authenticity The Cloisters’ Standing Bishop Attributed to Tilman Riemenschneider Michele D. Marincola and Jack Soultanian 1975, Standing Bishop was acquired for The Cloisters collection, the Metropolitan Museum of IArt, New York. This piece—considered at purchase to be a mature work of Tilman Riemenschneider (ca. 1460–1531), a leading German mas- ter of Late Gothic sculpture—was intended to complement early works by the artist already in the collection. The sculpture (Fig. 1) is indisputably in the style of Riemenschneider; furthermore, its provenance (established to before 1907) includes the renowned Munich collection of Julius Böhler.1 The Standing Bishop was accepted as an autograph work by the great Riemenschneider scholar Justus Bier (1956), who was reversing his earlier opinion. It has been compared stylistically to a number of works by Riemenschneider from about 1505–10. In the 1970s, a research project was begun by art historians and conservators in Germany to establish the chronology and authorship of a group of sculptures thought to be early works of Riemenschneider. The Cloisters’ sculptures, including the Standing Bishop, were examined as part of the project, and cross sections were sent to Munich for analysis by Hermann Kühn. This research project resulted in an exhibition of the early work of Riemenschneider in Würzburg in 1981; The Cloisters sent two sculptures from its collection, but the loan of the Standing Bishop was not requested. Certain stylistic anomalies of the figure, as well as several Figure 1 technical peculiarities discussed below, contributed to the increasing suspi- Standing Bishop, attributed to Tilman cion that it was not of the period. -

IFA-Annual-2018.Pdf

Your destination for the past, present, and future of art. Table of Contents 2 W e l c o m e f r o m t h e D i r e c t o r 4 M e s s a g e f r o m t h e C h a i r 7 T h e I n s t i t u t e | A B r i e f H i s t o r y 8 Institute F a c u l t y a n d F i e l d s o f S t u d y 14 Honorary F e l l o w s h i p 15 Distinguished A l u m n a 16 Institute S t a f f 1 9 I n M e m o r i a m 2 4 F a c u l t y Accomplishments 30 Spotlight o n F a c u l t y R e s e a r c h 4 2 S t u d e n t V o i c e s : A r t H i s t o r y 4 6 S t u d e n t V o i c e s : Conservation 50 Exhibitions a t t h e I n s t i t u t e 5 7 S t u d e n t Achievements 6 1 A l u m n i i n t h e F i e l d 6 8 S t u d y a t t h e I n s t i t u t e 73 Institute S u p p o r t e d Excavations 7 4 C o u r s e H i g h l i g h t s 82 Institute G r a d u a t e s 8 7 P u b l i c Programming 100 Support U s Art History and Archaeology The Conservation Center The James B. -

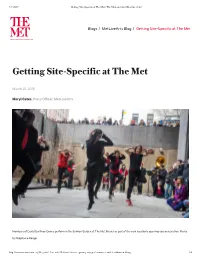

Getting Site-Specific at the Met

4/4/2017 Getting Site-Specific at The Met | The Metropolitan Museum of Art Blogs / MetLiveArts Blog / Getting Site-Specific at The Met Getting Site-Specific at The Met March 25, 2016 Meryl Cates, Press Officer, MetLiveArts Members of David Dorfman Dance perform in the Sunken Garden at The Met Breuer as part of the new location's opening-day celebration. Photo by Stephanie Berger http://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/met-live-arts/2016/met-breuer-opening-day-performances-and-stockhausen-klang 1/6 4/4/2017 Getting Site-Specific at The Met | The Metropolitan Museum of Art The Met Breuer has been open just one week, and already several site-specific works have animated the iconic building on Madison Avenue at 75th Street. On the opening day, March 18, David Dorfman Dance led the way with an inspired performance created for the outdoor Sunken Garden. A buoyant work, the dancers commanded the space with arresting lifts that were creatively crafted using the building itself as support. Dorfman's choreography and the music by Ken Thomson and Friends was completely captivating, and offered a satisfying and unexpected intimacy—no small feat for such a large opening-day celebration. Audiences lined the Garden, windows, sidewalks—wherever there was a view—for each of the day's six performances. It is easy to romanticize The Met Breuer as an ideal location for site-specific live arts. The building boasts subtle details that continue to unfold and further reveal themselves, visit after visit. To see live arts staged with such beauty and nuance is an exciting sign of what's to come in future seasons. -

Egyptian Life from Small to Tall the Egyptian Galleries

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART A GALLERY GUIDE FOR FAMILIES Egyptian Life from Small to Tall The Egyptian Galleries z\ J— o Dool ,trjjn|33" c Temple of Dendur, Sackler Wing Suggested route of guide ...r1 a ••-:• •X in K •-•• The Metropolitan Museum of Art A Gallery Guide for Families Egyptian Life from Small to Tall This publication was made possible by a generous grant from The Gap Foundation Mediterranean Sea EGYPT When you see or hear the word Egypt, what do you think of? Write down some ideas here: Maybe you thought of sphinxes and mummies. Or temples and tombs. Whatever you imagined, there's a good chance you'll see it on your trip here. This guide will take you through the Egyptian galleries in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. You'll see some things that are really DI £ and others that are so small you might walk right by without noticing them. The Egyptians made many of the same forms in sizes ranging from tiny to huge. See if you can spot the same forms in different sizes as you walk around. Here are some things to keep in mind: Use this booklet as a guide. Check out the map of the galleries on the inside front cover for extra help. As you walk around you'll notice many wonderful things not included here. But don't try to see everything in one day — you'll just get tired and grumpy. Be kind to your feet and save some things to see on your next trip here. -

The Asse to the Harpe: Boethian Music in Chaucer

XI THE ASSE TO THE HARPE: BOETHIAN MUSIC IN CHAUCER ‘What! slombrestow as in a litargie? Or artow lik an asse to the harpe, That hereth sown whan men the strynges plye, But in his mynde of that no melodie May sinken hym to gladen, for that he So dul ys of his bestialite?’ Andarus, love’s preceptor, cries out these words in exasperation at the P love-lorn Troilus who has spurned his elegant rhetorical consolatio .1 The words are borrowed from Boethius’ Philosophia who had uttered them in a tone of similar exasperation: ‘Sentisne, inquit, haec atque animo illabuntur tuo an ὄνος λυρας?’ she says after having sung to him Metrum 4, ‘Quisquis composito serenus aevo’. Chaucer translated this passage: ‘Felistow’, quod sche, ‘thise thynges, and entren thei aught in thy corage? Artow like an asse to the harpe?’ 2 In Troilus and Criseyde , probably written while Chaucer was translating Boece (see ‘Chaucer’s Wordes unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn’), 3 Chaucer carried the asinus ad liram topos further than did Boethius. He has it jangle even more discordantly in Pandarus’ mouth – the advocate of lust – being wrenched out of context by Chaucer’s Pandarus from Boethius’ Philosophia. Pandarus is the schoolmaster of lust while Philosophia is the schoolmistress of reason. Though one apes the other, yet they are diametrically opposed. Besides the rhetorical topos of the Ass to the Harpe there is also an extensive iconographic use of the harp-playing ass. An inlay on the soundbox of a sacred harp from Ur, circa 2600 B.C., shows an ass playing a lyre with other figures. -

MEDIEVAL ART a Resource for Educators

MEDIEVAL ART A Resource for Educators THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s teacher-training programs and accompanying materials are made possible through a generous grant from Mr. and Mrs. Frederick P. Rose. Copyright © 2005 byThe Metropolitan Museum of Art,NewYork Published byThe Metropolitan Museum of Art,NewYork Written by Michael Norris with the assistance of Rebecca Arkenberg,Meredith Fluke, TerryMcDonald,and RobertTheo Margelony Project Manager: Catherine Fukushima Senior Managing Editor: Merantine Hens Senior Publishing and Creative Manager: Masha Turchinsky Design byTsang Seymour Design Inc.,NewYork Color separations and printing by Galvanic Printing & Plate Co.,Inc.,Moonachie,New Jersey Photographs of works in the Museum’s collections are by the Photograph Studio of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Figs. 2,3,6 byWilliam Keighley,The Metropolitan Museum of Art,all rights reserved; figs. 7,8 by Julien Chapuis; figs. 10,11 by NancyWu. Illustrations in the Techniques and Materials section by Meredith Fluke. Map by International Mapping Associates, Ellicott City,Maryland. Cover: Image 31: Saint Louis before Damietta (detail folio 173),from The Belles Heures of Jean of France,Duke of Berry,1406–8 or 1409; Limbourg Brothers (here perhaps Herman) (Franco- Netherlandish,active in France,by 1399–1416); French; Paris; 3 5 ink,tempera,and gold leaf on vellum; 9 ⁄8 x 6 ⁄8 in. (23.8 x 16.8 cm); The Cloisters Collection,1954 (54.1.1) isbn 1-58839-083-7 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) isbn 0-300-10196-1 (Yale University Press) Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress. -

The New Yorker’S (“The Arms Dealer,” P

MARCH 5, 2018 7 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 19 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Amy Davidson Sorkin on Mueller’s indictments; charting hatred’s rise; Edna O’Brien takes her tea; Lincoln drawn from life; the shoemaker’s cameo. A REPORTER AT LARGE Mike Spies 24 The Arms Dealer A lobbyist’s influence over Florida’s lawmakers. THE CONTROL OF NATURE John McPhee 32 Direct Eye Contact Dreaming of seeing a bear outside the window. SHOUTS & MURMURS Larry David 35 No Way to Say Goodbye PROFILES Tad Friend 36 Donald Glover Can’t Save You The actor, producer, and musician writes his script. LETTER FROM MEDELLÍN Jon Lee Anderson 50 The Afterlife of Pablo Escobar How the drug kingpin became a global brand. FICTION Nicole Krauss 60 “Seeing Ershadi” THE CRITICS ON STAGE Hilton Als 67 The standup comedy of Tiffany Haddish. BOOKS Kelefa Sanneh 70 Jordan Peterson against liberal values. 75 Briefly Noted Laura Miller 76 Uzodinma Iweala’s “Speak No Evil.” THE ART WORLD Peter Schjeldahl 78 New radicals at the New Museum’s Triennial. POP MUSIC Hua Hsu 80 The fuzzy identities of U.S. Girls. POEMS Idea Vilariño 46 “Alms” Rachel Coye 64 “New Year” COVER Chris Ware “Golden Opportunity” DRAWINGS David Sipress, Carolita Johnson, Navied Mahdavian, Danny Shanahan, Roz Chast, Christopher Weyant, P. C. Vey, Pia Guerra, Will McPhail, Maddie Dai, Drew Dernavich, Barbara Smaller, Edward Steed, Paul Noth, Jason Adam Katzenstein SPOTS Sergio Membrillas Where to go, what to do. CONTRIBUTORS Try Goings On About Town Mike Spies Tad Friend online, The New Yorker’s (“The Arms Dealer,” p.