Geopolitical Tamil Nadu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasures and Traditions of South India February 18- March 1, 2008

Treasures and Traditions of South India February 18- March 1, 2008 DETAILED ITINERARY (subject to amendment) Monday, February 18, 2008 The group departs New York on a flight to Chennai. (Meals aloft) Tuesday, February 19, 2008 Late this evening, we arrive at Chennai Airport. Upon arrival, we check-in at the Taj Connemara Hotel. Taj Connemara (meals aloft) Wednesday, February 20, 2008 The morning is at leisure. This afternoon, we enjoy a city tour by motorcoach, including a visit to the renowned Government Museum of Chennai. The Government Museum displays the largest and most spectacular collection of bronzes in India. Of particular note are the various Nataraja, or Dancing Shiva, created centuries apart and displaying the artistic styles of each period. This evening, we are treated to a welcome dinner under the stars featuring live music and dancers and fine South Indian cuisine. Taj Connemara (B, D) Thursday, February 21, 2008 At Mahabalipuram, a 7th century Pallava trading port and UNESCO World Heritage Site, we examine the sublime rock-cut temples of Mahabalipuram and the spectacular shore temple, a spectacular two-spired shrine, unique in that it houses both Vishnu and Shiva in its sanctum. We enjoy a delightful al fresco lunch on the Bay of Bengal, serenaded by the sounds of the waves crashing against the shore. Next, we learn about the architecture and crafts tradition of the four states of South India at Dakshinachitra. Using actual buildings transported and reconstructed from each state, Dakshinachitra gives visitors rare insight into how each state’s architecture varies based on environmental and economic factors, as well as how crafts are produced for the home. -

Welcome to CMI Outline

Introduction Academic Non-academic Chennai Welcome to CMI Outline 1 Introduction 2 Academic 3 Non-academic Hostel and other facilities Life outside home 4 Chennai Introduction Academic Non-academic Chennai This presentation is intended to: Make you aware of some important features of CMI Alert you to some potential problems you will face Inform you of all the facilities and resources available to you Emphasize your responsibilities Outline 1 Introduction 2 Academic 3 Non-academic Hostel and other facilities Life outside home 4 Chennai Students must get the approval of faculty advisor and relevant instructor before taking an elective. The complete list of electives must be submitted to the office by a deadline. For more information consult: CMI webpage Your instructors Faculty advisor Introduction Academic Non-academic Chennai Academic Structure Each degree requires a student to take a certain number of courses. core: these are compulsory courses electives: these are to be chosen by the student from among those offered Introduction Academic Non-academic Chennai Academic Structure Each degree requires a student to take a certain number of courses. core: these are compulsory courses electives: these are to be chosen by the student from among those offered Students must get the approval of faculty advisor and relevant instructor before taking an elective. The complete list of electives must be submitted to the office by a deadline. For more information consult: CMI webpage Your instructors Faculty advisor More importantly, you must feel free to consult your advisor in case of any confusion or difficulty. Introduction Academic Non-academic Chennai Academic Advisors Each batch of students is assigned a faculty advisor from the faculty. -

11309 MM Vol. XXI No. 11.Pmd

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/09-11 Registrar of Newspapers Licence to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. WPP 506/09-11 Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI INSIDE • Short ‘N’ Snappy • The Editor & Madras Week • Madras Week blogs • Tamil film publicity • Two men of letters Vol. XXI No. 11 MUSINGS September 16-30, 2011 Marina’s elevated road plans now abandoned You design whatever you want and however you want, but you know that – But is beach permanently safe? anyway I’m going to change it a hundred times...! he Tamil Nadu Govern- other places, some nowhere Tment has informed the near the coast. Secondly, it in- Building blocks High Court of Madras that it volved work being done at en- Buildings are a slightly worried lot has dropped the idea of build- vironmental hotspots such as these days. ing an elevated road along the the Theosophical Society, the Understandable. East Coast Road. The project Adyar Creek and the beach- Picture this. had faced strong protests from front, the last also being the You were created, even launched, as a symbol, a monument, to environmental activists and the nesting spot of the Olive Ridley the majesty and gravitas of au- fisherfolk right from inception. turtles. Thirdly, there was the thority. The decision to drop it has, question of whether the whole Then, suddenly, your role gets re- therefore, been widely wel- project would finally play into written. comed. But all this does not in the hands of the real estate You are now a supermarket. -

Iso/Tc 157 N934

ISO/TC 157 N934 35th MEETING of ISO/TC 157 NON-SYSTEMIC CONTRACEPTIVES AND STI BARRIER PROPHYLACTICS 17 -20 September 2018, Hotel Grand by GRT, T Nagar, Chennai, India HOSTED BY Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) 9 Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi-110002 India Tel : +91 11 23230910 / +91 11 23608292 Tele Fax : + 91 11 23230910 Email : [email protected] 35th MEETING FOR ISO/TC 157 NON-SYSTEMIC CONTRACEPTIVES AND STI BARRIER PROPHYLACTICS,CHENNAI,INDIA Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) is glad to invite you to the 35th meeting of ISO/TC 157 meeting being convened from 17th September 2018 to 20th September 2018 in Chennai, India. The venue for the above meeting is Hotel Grand by GRT, Chennai, India. We attach a copy of the meeting information for your reference. We wish to extend our best wishes to all delegates for a pleasant and memorable stay in Chennai and for productive outcome of your deliberations at the meeting. Page 1 of 9 ISO/TC 157 N934 35th MEETING of ISO/TC 157 NON-SYSTEMIC CONTRACEPTIVES AND STI BARRIER PROPHYLACTICS 17 -20 September 2018, Hotel Grand by GRT, T Nagar, Chennai, India 1. MEETING VENUE Hotel Grand by GRT, T Nagar, Chennai 120, Sir Thyagaraya Road, T.Nagar Chennai – 600017, Tamilnadu, India Phone : +91 44 2815 0500 Fax : +91 44 2815 0778 Email : [email protected] & [email protected] Website : www.grthotels.com Road MAP from Airport to Hotel Grand by GRT Page 2 of 9 ISO/TC 157 N934 35th MEETING of ISO/TC 157 NON-SYSTEMIC CONTRACEPTIVES AND STI BARRIER PROPHYLACTICS 17 -20 September 2018, Hotel Grand by GRT, T Nagar, Chennai, India 2. -

In This Issue Preparing for College: a Checklist Undergraduate Studies

January - February 2013 Vol 2 - Issue 4 - `100 In This Issue Preparing for College: A Checklist Undergraduate Studies: Destination Singapore Dyscalculia: Connecting the Dots Inculcating Good Study Habits Road Trips from your City It’s good with lots of information related to children. One article I really like is “Places to See”. It’s good and very important for kids to know about different places. It is also helpful for them in schools, since it is related to their subjects like history and geography. One suggestion: Your team should include articles I guess I am paranoid over somethings that I feel with information for parents about what are the are unique between me and my 4 year old, who options available on the internet in the field of thinks she is 25! But again, I guess it's every Mom's education. story....! Madhukar Wakade, Bangalore The same stuff....getting up, school, food, sleep, behaviour, respect to elders, etc.......!!! I’ll give myself a break, get a tea time coffee.....thank you It’s a good magazine with a lot of interesting topics Parent Edge for being there....!!! Kudos!! for parents; I have read a couple of your issues, which are amazing. Bhagirathi Panchal, Bangalore Mohan Pandit, Pune It’s a good magazine with articles related to children, which are useful for parents and teachers, It’s a good magazine and informative, with lot of to know how to handle them. And over all its nice information regarding children, which helps parents magazine. to know what is best for their kids regarding schools, food, clothes, college etc. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 22:3 — Fall 2010 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2010 Textile Society of America Newsletter 22:3 — Fall 2010 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 22:3 — Fall 2010" (2010). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 59. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/59 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Textile VOLUME 22 n NUMBER 3 n FALL, 2010 Society of America Reflections of A Symposium Co-Chair by Wendy Weiss CO N TE N TS UGUST 2010 MARKS TWO show of weavings mediated by serve as on-site hosts whenever years since we started digital technology. You can get their work schedules allow. 1 Symposium: Reflections Aplanning this coming a sneak preview of “American The Book Fair Committee 2 Symposium: Dyes & Color Symposium in earnest. By this Tapestry Biennial Eight” (ATB8) at: has secured an excellent selec- 3 From the President time two years ago, Co-Chair http://americantapestryalliance.org/ tion of books representing TSA Diane Vigna and I had met Exhibitions/ATBs/ATB8/ATB8.html authors and more, available 4 TSA News with TSA Board members at Rebecca Stevens juried this exhi- for you to purchase and have 6 TSA Member News the Spring, 2008 meeting in bition and some of the artists shipped home. -

Trading on Culture: Planning the 21St Century City

Trading on Culture: Planning the 21st Century City Industrial Relocation Leads to Artistic Appreciation When the future is in doubt, look to your heritage. A new UN-HABITAT publication, The State of the World’s Cities Report, 2004, illustrates the growing trend of refurbishing and re-branding cities as cultural havens - a creative attempt by many local governments to revitalize economies in need of urban renewal mechanisms. As more and more cities seek to sustain themselves in the wake of the industrial flight that often accompanies globalization, many are being recreated as “cities of culture.” Whether or not a city has a cultural heritage to draw upon, or merely a survivalist’s need to succeed, banking on the financial draws of culture – be it artistic, historic, athletic or religious - has proved to be a blessing for many urban officials and planners. However, as with the many endeavours that globalization engenders, this new exercise in artistic appreciation has forced many of the urban poor and middle-class into an exodus out of the cities that no longer seem to appreciate them. Current trends in many parts of the world suggest that culture will play an increasingly important role in the future of cities. The culturally driven redevelopment of inner-city areas has included the preservation of historic buildings as well as revival of traditional crafts for enhancing the global tourism potential of cities; and gentrification of inner-city residential areas. Gentrification has transformed the older sections of many cities into some of the most sought-after real estate. These restored buildings may now glisten in all their historical splendor, but they are no longer home to the people who, historically, used to live in them. -

Rohaan Oasis-II

https://www.propertywala.com/rohaan-oasis-ii-chennai Rohaan Oasis-II - Perambakkam, Chennai 2 BHK apartments available at Rohaan Oasis-II Rohaan Constructions presents Rohaan Oasis-II with 2 BHK apartments available at Perumbakkam, Chennai Project ID : J811900323 Builder: Rohaan Constructions Properties: Apartments / Flats Location: Rohaan Oasis-II, Perambakkam, Chennai - 600100 (Tamil Nadu) Completion Date: Mar, 2015 Status: Started Description Rohaan Constructions presents a beautiful project that is Rohaan Oasis - II which is located in Rukmani Nagar. It is a opulent project that boasts of luxurious apartments. The residency consists of spacious apartments and gives a quality construction. It offers an array of desirable amenities that together ensure a serene way of living and makes the life of its residents comfortable and hassle free. The projects give pure and eco-friendly living. The view from every apartment is breath taking, enveloped with lush of greenery. Oasis II is a efficiency of design, spaciousness and preferred location are the key features of this residence. Amenities Car Parking Vastu Compliant 24 Hour Electricity Park Rain Water Harvesting 24 Hour Water Supply Community Hall Rohaan Constructions is having an established credibility and a consistent record of superior performance, timeless style and timely delivery. The company design construct and maintain residential and commercial buildings. They aim transparency and commitment to the customers. The key feature of the company is their technological skills and new age vision towards the construction industry. The company is continuously improving and transforming into a dynamic and forward thinking company. They provide the highest standard quality of construction and timely completion of project. -

Pearson Travel Guide & Cognizant Value Book

ALWAYS INNOVATING ALWAYS TRANSFORMING Pearson Travel Guide & Cognizant Value Book February 27, 2015 BOUND BY PARTNERSHIP & Sunil Rajan Global Client Partner Mobile: +44 779 522 0276 Email: [email protected] ARTNERS P Ashok Thambi Krishnan Senior Account Manager, NA Venkatachalam Mobile: Global Delivery Partner +1-201-417-1491 Mobile: +91-984-018-9637 Email: Email: Venkatachalam. Ashok.KumarThambi@ [email protected] cognizant.com OMMITTED Somnath Mondal Ramprasad Senior Account Manager, UK Varadarajan (Ram) Mobile: Delivery Manager C +44 777-177-5611 Mobile: +919003034098 Email: Email: Ramprasad.Varadharajan@ Somnath.Mondal@ cognizant.com cognizant.com OUR Y ALWAYS INNOVATING 2 ALWAYS TRANSFORMING Cognizant Technology Solutions 500 Frank W. Burr Blvd. Teaneck, NJ 07666 Ph: +1 201 801 0233 Fax: +1 201 801 0243 E-mail: [email protected] On behalf of Cognizant, we would like to extend a warm welcome to you upon your visit to our Chennai facilities. It is truly our pleasure to host you during your time in India. We hope that your trip is rewarding and memorable. We recognize the trip to India is a signifi cant investment of your valuable time and, to that end, we have put together an agenda, which we feel gives you deeper understanding of our capabilities, culture and the quality of work we do. We hope you enjoy this book, and we look forward to seeing you soon! Sincerely, Ramachandran Meenakshisundaram Global Head of Delivery Information, Media & Entertainment Business Unit BOUND BY PARTNERSHIP & 3 INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT INDIA Historical & Cultural: • The name ‘India’ is derived from the River Indus, the valleys around which were the home of the early settlers. -

15097 MM Vol. XXV No. 5.Pmd

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/15-17 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/15-17 Publication: 15th & 28th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI INSIDE • Short ‘N’ Snappy • Saving our classical wealth • Remembering Gopulu • An affection for Chennai • Life with the staff Vol. XXV No. 5 MUSINGS June 16-30, 2015 Global investors Know your Fort Some City better showpieces to light up (By A Staff Reporter) t is learnt that of Chennai’s I800 heritage buildings of Architectural, Historical, heritage Cultural and Aesthetical interest. 36 Grade-I heritage buildings in the stretch from Chennai Airport to Secre- G by The Editor tariat Building, George Town, will be externally improved and floodlit to greet dignitaries visiting and t is not clear though it is clear as to how these can be attending the Investors’ Meet Ihoped that our State will floodlit. Take for instance the scheduled to be held in the benefit economically from the Madras Club and the Theo- The Cupola in the Fort, as seen today. city in September. Govern- Global Investors’ Meet, but 36 sophical Society – which parts G If you are not a VIP, you enter the Fort through a small side ment, it would appear, is at heritage buildings of our city of these campuses are to be illu- entrance – not for you the joy of sweeping up the driveway in your last waking up to the fact definitely will. -

Draft Routing Proposal Only

Our Personal Guest, Inc. || Agni || The delicacies by Indian fire DATE SOUTH INDIA PROGRAM REMARKS It’s not what you taste It’s what you spice your memory with Agni – Fire, since it was tamed by ancient Indians, it has been the residing deity of all things culinary. Enjoy the rich and exotic ten day culinary trip down the spice-laden trail of South India or up North India. Sink your teeth into succulent meats gently teased by Indian fire or savor the melting taste of fragrant rice prepared over charcoal. Medium, rare or well done, Agni in its different forms serves you cuisine to your ultimate satisfaction. Camellia Panjabi, arguably India’s foremost gourmet and food expert, a legend throughout the culinary world and credited with introducing regional Indian cooking to the UK, besides being the author of the best selling “ 50 Great Curries of India” will be planning, to the last detail, all the culinary inputs for you for this incredible journey. She is one of the directors of Masala World, which owns Chutney Mary, Veeraswamy, Amaya and several Masala Zone restaurants in London. Camellia as your Cuisine Curator…..It couldn’t get better than this! While on this culinary holiday you will enjoy personal, hands-on cooking sessions with acclaimed chefs at the Taj Hotels and escorted visits that will include shopping in local markets for fresh produce and spices -the raw materials for cooking your lunch, celebratory meals hosted by the chefs, et al. In South India you will sojourn at Fisherman’s Cove - Chennai, Taj Garden Retreat- Madurai and Taj Malabar – Kochi. -

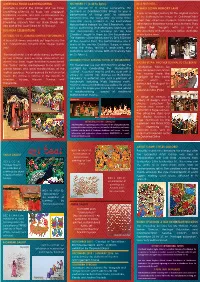

Greetings from Dakshinachitra Dusshera

GREETINGS FROM DAKSHINACHITRA OCTOBER 11 (3.30 to 5pm): IN A NUTSHELL... Dusshera is round the corner and we have Treat yourself to a unique experience this A WALK DOWN MEMORY LANE everything planned to keep you engaged! Dusshera as DakshinaChitra brings to you a It was a nostalgic journey for the original owners Traditional festivals and folk performances by performance of ‘living dolls’ to celebrate of the Kuthatukulam house at DakshinaChitra talented artists welcome you this season. Navaratri Kolu. The ‘living dolls’ are none other when they visited our museum. Fond memories Interesting snippets from our close friends are than the young students of the Rukminidevi Natyakshetra trained by Shri S.Premnath, who attached to the place came back to them. They also part of this issue! Read on to find out... will be performing Bharatnatyam. Members will shared their thoughts with us and a DUSSHERA CELEBRATIONS also demonstrate a ‘spinning on the box documentary of that interview will be available OCTOBER 7 TO 11: SOMANA KUNITHA PERFORMANCE Charkha’ taught to them by Shri Karunakaran. in our library soon. The dances will be introduced by Dr.V.R.Devika A beautiful dance ensemble put together by Shri of The Aseema Trust. The performances are in D.S. Gangadhara Gowda and troupe awaits praise of the mother Goddess, Durga, in whose you! name the 9-day festival is dedicated, and Mahatma Gandhi whose birth anniversary falls ‘Somana Kunita’ is a ritualistic dance performed on October 2. by two or three artists wearing masks which are DECEMBER 19 TO 27: NATIONAL FESTIVAL OF ‘MAHARASHTRA’ almost four times larger than the human head.