Opening Doors: Employing the Disabled. INSTITUTION Arizona State Dept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Work Sharing: Issues, Policy Options, and Prospects

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 201 819 ZIT 028 AUTHOR Best, 7r-red TI-TLE Work E_-ari.ng:ISSUE Folic- and Trsrri7TOT7ON Upjohn (W.E.) Inst. or 7.mn _cm Reearch Kalama=on, Mich. FPOFT ISBN-C--1 1558-79-9: 7-7-13 r_.) A 81 772r 217p. A"-AILABLE FROM W. E. ute for :Plc 300 S. westnr-e Ave., Kal_am=o, "7 .nad cov $8.00: paper, $5.0.. oi available). 7Dpq MF01 Plus Postage. DESCPIP7ORS Adults; Economic N-1-mx__,m7gri_csnn CPorr ies: *Employment_ Practi es: -ime -Employment; *Public Policy .1-73c-fai *Ur.employment 77EN77-1.-7-7 S Impact; *Job Sharing This monograph reviews zurren- 77--:':_'eVa---7:erofwork sharing and assesses cr7.-.-a4-_i-or. potential, and likely socia_l__ pac ate:1 t7 the concept. Chapter r. overvi 'A977_"_147. sg n -oast .7-4:haring as an alternative to the (mt. anemplo-rmer-t in fulre_ Chapter 2 reviews issues of 7-0771r. ',I a :1.7'1g :The se c--.-7--_;_dera-tio7s are consolidated into thsthe o mpac.t.- :7-=3uc-oivityand price stability, job participation and aggregate er.p-Lovz---....- sociefL eguitY -tar-7eta.bility,flexibility of impl_e_men. 7,--_rative costs and reaulatory secoaLt.= cr.ncerrs. Chapter 3 focuses on sevetezy-:-:- de,---7!:Tcrne:a to redistribute existin: and oros--pe_-_=.:LvE: oppo-rtin-itles through work sharing. They major catego=i.-es: (1) subsidized worktime reduct.t.--.7 (2) .lim.Ltation of worktime (5 options), trade-cs (4 options) , and(4) voluntary -:=Ezda-off options for individuals (2 options). -

Alternative Work Arrangements 1

Running head: ALTERNATIVE WORK ARRANGEMENTS 1 Alternative Work Arrangements An Examination of Job Sharing, Compressed Workweeks, and Flextime Joseph Lutz A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2012 ALTERNATIVE WORK ARRANGEMENTS 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Colleen McLaughlin, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ David Duby, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ David Snead, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ALTERNATIVE WORK ARRANGEMENTS 3 Abstract Alternative working arrangements have become increasingly popular in workplaces across America and the world. One segment of alternative work arrangements is schedule flexibility. The three types of flexible schedules examined include: job sharing, compressed workweeks, and flextime. Each arrangement will be examined individually. First, a definition and background information will be given. Then, the benefits of the arrangement will be discussed. Next, the risks and challenges of the arrangement will be examined. Finally, there will be analysis of what conditions are necessary for the arrangement to be successful. ALTERNATIVE WORK ARRANGEMENTS 4 Alternative Work Arrangements An Examination of Job Sharing, Compressed Workweeks, and Flextime In recent years, as businesses have become more focused on employee needs and their own productivity, alternative work arrangements have grown in popularity. Alternative work arrangements, sometimes known as flexible work arrangements or alternative work schedules, can be explained as any work arrangement that deviates from the standard workweek. To gain a full understanding of alternative work arrangements, an understanding of the standard workweek and its history must first be established. -

The Brain Injury Handbook: a Resource Guide for Employers

I was hit by a drunk driver. I tripped and hit my head. I was assaulted leaving work. The Brain Injury Handbook: A Resource Guide for Employers I sustained a blast injury in Iraq. My ex-boyfriend beat me up. I had a heart attack. 1 of 64 The Brain Injury Handbook: An Introductory Guide to Understanding Brain Injury for Employers 2011 Sherry Stock, Executive Director Brain Injury Association of Oregon, Inc. PO Box 549, Molalla OR 97038 800-544-5243 www.biaoregon.org These materials were funded by the Oregon State Rehabilitation Services Grant # 136164. Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 Injury and Disability Prevalence Rates ................................................................................ 1 What Are Acquired and Traumatic Brain Injuries? ............................................................... 1 What is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder? ............................................................................ 2 The Goal: A Return to Work ............................................................................................... 2 2. INFORMATION FOR EMPLOYERS ABOUT ABI/TBI .................................................................. 2 The Role of Employers ........................................................................................................ 3 3. THE HUMAN BRAIN AND TBI/ABI ........................................................................................ 4 Structure -

What Is Job-Sharing?

International Labour Office Geneva Work-sharing and job-sharing What is work-sharing? ork-sharing is a reduction of working time intended to spread a given volume W of work over a larger number of workers in order to avoid layoffs or increase employment. The decrease in working hours is mostly coupled with cuts in wages and benefits, which, in turn, may be partially compensated by government wage subsidies or often social benefits (e.g. unemployment compensation). The extent of the reduction in workers’ wages and benefits may or may not be proportional to the extent of the reduction in working hours. What is job-sharing? ob-sharing, by contrast, refers to a voluntary arrangement whereby two persons take J joint responsibility for one full-time job and divide the time they spend on it according to specific arrangements made with the employer. A common form of job-sharing is to split one full-time job into two part-time jobs (for more information about part-time jobs, see Information Sheet No. WT-4 on part-time work). Unlike work-sharing, job-sharing is generally not used as a measure to avoid layoffs or increase employment. How are work-sharing and job-sharing constrained or promoted? any countries facilitate work-sharing as a labour market policy tool aimed at M preserving existing jobs or creating new ones. In the framework of national work- sharing programmes, firms can receive benefits when they refrain from the use of layoffs, and instead “share” the (lower) amount of available work by reducing working hours per employee, although typically the hours worked per employee are not reduced to part-time levels. -

Interwar Unemployment in International Perspective

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #12-88 April 1988 Interwar Unemployment In International Perspective Barry Eichengreen and Tim Hatton Cite as: Barry Eichengreen and Tim Hatton. (1988). “Interwar Unemployment In International Perspective.” IRLE Working Paper No. 12-88. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/12-88.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment UC Berkeley Title: Interwar Unemployment in International Perspective Author: Eichengreen, Barry, University of California, Berkeley Hatton, Tim, University of Essex Publication Date: 04-01-1988 Series: Working Paper Series Publication Info: Working Paper Series, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, UC Berkeley Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bw188gk Keywords: Eichengreen, Hatton, unemployment, international perspective Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. Interwar Unemployment in International Perspective Barry Eichengreen University of California, Berkeley Tim Hatton University of Essex January 1988 This paper is the editors' introduction to a volume of the same name, to be published by Martinus Nijhoff later this year. INTERWAR UNEMPLOYMENT IN INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE The outstanding internal economic problem of the interwar period in all countries studied was undoubtedly unemployment. Next to war, unemployment has been the most widespread, most insidious and most corroding malady of our generation; it is the specific disease of western countries in our time. -

“Practical Guide” on Job Sharing

A PRACTICAL GUIDE JOB SHARING TWO PROFESSIONALS FOR THE PRICE OF ONE CONTENTS PART-TIME WORK AND THE LABOUR MARKET 1 A MODEL FOR ALL AGES 3 DEFINITION OF JOB SHARING 4 LEGAL ISSUES 5 ADVANTAGES 8 CHALLENGES AND CONSTRAINTS 9 ORGANISATION 10 INTERGENERATIONAL JOB SHARING 11 The Go-for-jobsharing THE IDEAL PARTNER AND THE JOB APPLICATION 12 initiative is supported by the Federal Office for Gender Equality. ENSURING A SUCCESSFUL JOB SHARE 15 Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA TESTIMONIALS 16 Federal Office for Gender Equality FOGE Funded under the Equal Opportunities Act PERCEPTION WITHIN THE ORGANISATION 18 WHEN A PARTNERSHIP ENDS 19 EDITED AND PRINTED BY Authors : Irenka Krone-Germann SUPPORT FROM THE TOP 20 and Anne de Chambrier, Association PTO Graphic design : THE 10 STEPS TO JOB SHARING 21 Contreforme sàrl Photographs : Keren Bisaz (Introduction, p. 1 and p. 25) TESTIMONIALS 22 www.miragesphoto.com Photograph on p. 1 taken at Kelly Services in Fribourg USEFUL WEBSITES IN SWITZERLAND 25 Proofreading : Anne Kelleher Cuendet February 2015 INTRODUCTION Dear Readers, The number of part-time workers has grown steadily in Switzerland over a number of years, especially among women. With one-third of its working population holding part-time positions, Switzerland is virtually the European record-holder where part-time work is concerned, just after the Netherlands. Yet despite the fact that part-time positions help provide work-life balance, these jobs have a number of disadvantages. For example, part-time positions are not typically advertised, but rather granted at the specific request of the employees. Part-time work is rarely offered for positions with a high-level of responsibility, makes it difficult for a part-time employee to change jobs even within the company and hinders the employer’s abililty to ensure coverage at the workplace every day of the week. -

Compensation

GUIDE 3 Compensation KEY TOPICS audit compensation philosophy compensation policy compensation structure discrimination external equity flexible work internal equity merit office housework opportunity gap parity productivity socioeconomic inequality suppressed earnings transparency value of work wage gap Compensation issues exist throughout our profession arising from inequitable opportunities, valuation of work, and pay practices. Removing compensation gaps supports the influx, development, and retention of talent and the economic stability and growth of individuals, firms, and the profession. This guide discusses current wage gaps in architecture, how they occur, and what their impacts are and suggests steps for evaluating, establishing, and maintaining equity and parity in compensation. The University of Minnesota for the American Institute of Architects Equity and the Future of 3Architecture Committee 3.02 GUIDE 3 * COMPENSATION WHAT IS IT? What is compensation? Compensation is the sum of all tangible GAPS Women in the United States earn 80 cents per dollar and intangible value provided by earned by men for full-time work.1 That compensation employers to employees in exchange for in the United States is neither equal nor equitable is work. Employers use compensation to clearly reflected in the wage gaps that exist between almost every demographic—gender, gender identity, attract, recognize, and retain employees. sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, physical ability, Employees use it to achieve a standard age—for both salaried and hourly workers, regardless of living, gauge the relative value of their of education level, occupation, or industry.2 Here are additional gaps as of 2017: Compared to a dollar earned work contribution to an employer and to by white men, Asian women earn 87 cents, white women society, and make employment choices. -

Employee Handbook May 2018 Final.Pdf

Missouri Department of Transportation EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK Human Resources Division Revised May 2018 - Replaces January 2017 An Affirmative Action/EEO Employer, M/F Contents PREFACE Welcome 1 How to Use Your Employee Handbook 2 Mission Statement 3 Values 4 Results 5 Commission and Department Organization 6 PART 1 – EMPLOYMENT About Your Job 7 Personnel Files and Employee Records 7 Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) 7 Loss of Driving Privileges 8 Loss of Personal Property 8 Permanent Part-Time and Job Share Employment 8 Probationary Period 9 Preferred Employee Qualities 9 Diversity and Inclusion 9 Competitive Promotions and Advancement 9 Career Ladder Promotions 10 Demotion 10 Waiver of Job Specification Minimum Requirements 11 Substitution of Education or Experience 11 Employment of Relatives 11 Resignation 12 Temporary Modified Duty 12 Vehicle Liability 12 Work Hours 12 Telework 12 Background Checks 13 PART 2 – CONDUCT Alcohol Testing 13 Drug-Free Workplace 13 Drug Testing 14 Disclosure of Confidential Information 14 Communications and Information Systems 14 Outside Employment 15 i Performance/Conduct Intervention 15 Standard Rules of Conduct 15 Fraud, Waste, and Abuse 16 Political Activity 16 Attendance 17 Safety 17 Smoking and Tobacco Use 17 Use of State Vehicle 18 Workplace Security 18 Workplace Relationships 18 PART 3 – COMPENSATION AND BENEFITS Benefits Cafeteria Plan 18 Deferred Compensation 19 Deductions 19 Employee Training Opportunities 19 Educational Assistance 19 Work Life Balance Program 20 Employee Assistance Program 20 Public -

Civil Service Guide to Job-Sharing Practical Advice for Job-Sharers, Their Managers and Their Teams

Civil Service guide to job-sharing Practical advice for job-sharers, their managers and their teams 0 Introduction When job-sharing works well, it works very well, and brings lots of advantages, both for individuals and for their departments. Job-sharers can get the balance they want between work and the rest of their lives, and still take on a job with the full range of responsibilities. For the Civil Service, job-sharing (among the range of flexible working options) allows us to hold on to, and make the most of, staff skills and experiences. For managers and teams, job-sharing brings the advantage of two sets of skills, experience and ideas to any one post. At the same time, if you’re thinking about job-sharing, or, as a manager, taking on job-sharers in your team, you need to be aware of the potential challenges and manage them proactively. The key to successful job-sharing is good and clear communication structures, both with one another and with all colleagues and stakeholders. Having two sets of skills and ideas is a real strength of job-sharing; but job- sharers need to work hard behind the scenes to give their colleagues a clear and consistent approach. Every job-share partnership is different, and depending on the work you do, your particular working styles, and the needs of your colleagues, you’ll need to decide your way of making it work. The suggestions in this report are designed to help you do that. Many employees working in the Civil Service have made a success of job- sharing. -

Employee Handbook HR Suite Master

Employee Handbook HR Suite Master Table of Contents • Section 1000: Introduction and Employee Acknowledgement o Policy 1001: Employee Handbook Receipt and Acknowledgement o Policy 1005: HR Department o Policy 1010: Introduction to the Handbook o Policy 1020: Message from Management o Policy 1030: Mission Statement o Policy 1040: Overview of the Credit Union • Section 2000: General Management Practices o Policy 2010: Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) o Policy 2015: Diversity o Policy 2020: Employment-At-Will o Policy 2030: Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) o Policy 2040: Harassment • Section 3000: Employment Status and Human Resource Records o Policy 3010: Employee Classification o Policy 3020: Initial Employment Period o Policy 3030: Human Resources Files and Records o Policy 3040: Reference Requests • Section 4000: Employment Practices o Policy 4005: Alternate Working Schedules o Policy 4010: Complaint Procedure o Policy 4020: Corrective Action o Policy 4023: Emergency Closing o Policy 4024: Employee Development o Policy 4025: Employee Referral Program o Policy 4026: Employment of Minors o Policy 4030: Hiring of Relatives (Nepotism) o Policy 4032: Immigration Law Compliance o Policy 4033: In-House Education and Training o Policy 4034: Internships o Policy 4035: Involvement in Community/Political Activities o Policy 4036: Job Sharing o Policy 4039: Matching Gift Program o Policy 4040: Medical Exams, Drug Testing, and Health Certification o Policy 4048: Orientation o Policy 4050: Outside Employment o Policy 4060: Performance Appraisal -

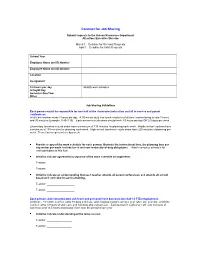

Job Sharing Guidelines

Contract for Job Sharing Submit requests to the Human Resources Department Attention: Executive Director March 1 – Deadline for Renewal Requests April 1 – Deadline for Initial Requests School Year Employee Name and ID Number Employee Name and ID Number Location Assignment 3.5 hours per day Identify work schedule A Day/B Day Semester One/Two Other Job Sharing Guidelines Each person would be responsible for one-half of the classroom instruction and all in-service and parent conferences. A full time teacher works 7 hours per day. A 30 minute duty free lunch results in a full time teacher being on site 7 hours and 30 minutes (Example: 7:45-3:15). Each person in a job share should work 3.5 hours per day OR 2.5 days per week. Elementary teachers in a job share have a minimum of 135 minutes for planning each week. Middle school teachers have a minimum of 135 minutes for planning each week. High school teachers in a job share have 225 minutes of planning per week. These times represent a 5 day week. Provide a copy of the work schedule for each person. Illustrate the instructional time, the planning time per day and/or per week. Include lunch and non-instructional duty obligations. Attach complete schedule for each participant to this form. Initial to indicate agreement/acceptance of the work schedule arrangements. Teacher: ___________________ Teacher: ___________________ Initial to indicate an understanding that each teacher attends all parent conferences and attends all school based and curricular in-service training. Teacher: ___________________ Teacher: ___________________ Each person shall earn pro-rated sick leave and personal leave based on one-half (.5 FTE) employment. -

Women in the Workplace and Management Practices: Theory and Evidence

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 10788 Women in the Workplace and Management Practices: Theory and Evidence Takao Kato Naomi Kodama MAY 2017 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 10788 Women in the Workplace and Management Practices: Theory and Evidence Takao Kato Colgate University, IZA, Rutgers University, TCER, CJEB, CCP and ETLA Naomi Kodama Hitotsubashi University and RIETI MAY 2017 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 10788 MAY 2017 ABSTRACT Women in the Workplace and Management Practices: Theory and Evidence* We review recent studies on management practices and their consequences for women in the workplace.