Towards the Identification of Lampreys (Lampetra SPP.) in Archaeological Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Lamprey My Scientific Name Did You Know? Entosphenus Tridentatus Zzpacific Lampreys Spawn Between March and July

external pharyngeal (gill) slits anterior dorsal fin posterior dorsal fin buccal papillae caudal fin tail PacifIC Lamprey My ScientifIc Name Did you know? Entosphenus tridentatus zzPacific lampreys spawn between March and July. Males and females both construct nests--known as redds-- by moving stones with their By the Numbers mouths. Adults typically die within 3-36 days after spawning. As adults, we lamprey range in size from about 15 to 25 zzAfter larval lamprey (ammocoetes) hatch, they drift downstream to inches. We have been caught in depths ranging from areas with slower water velocity and fine sand for them to burrow 300 to 2,600 feet, and as far as 62 miles off the west into. Ammocoetes will grow and live in riverbeds and streambeds for coast of the United States! 2 to 7 years, where they mainly filter feed on algae. zzThe metamorphosis of Pacific lamprey from ammocoetes into How to Identify Me macropthalmia (juveniles) occurs gradually over several months. I belong to a primitive group of fishes that are eel-like That’s when they develop eyes, teeth, and emerge from substrate to in form but that lack the jaws and paired fins of true swimming. This transformation typically begins in the summer and is completed by winter. fishes. I have a round, sucker-like mouth, no scales, and seven breathing holes on each side of my body instead zzJuvenile lampreys drift or swim downstream to the estuaries of gills. I also don’t have any bones; my backbone is between late fall and spring. They mature into adults during this made of cartilage, like the stuff that makes up your ear! migration and when they reach the open ocean. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

XIV. Appendices

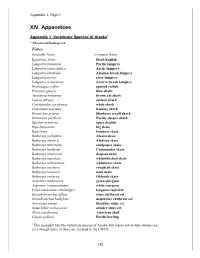

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

Learning Lessons About Lampreys Don Orth

Learning Lessons about Lampreys Don Orth 11 American Currents Vol. 43, No. 3 LEARNING LESSONS ABOUT LAMPREYS Don Orth Virginia Tech University, Blacksburg, Virginia Lampreys are simple fish that leave me with many ques- tiative emerged. Will the Pacific Lamprey ever recover? The tions. Lampreys and hagfishes are genetically very similar Lost Fish movie tells an all too familiar story (Freshwaters and represent the oldest living groups of vertebrates (Fig- Illustrated 2015) of the loss of important fish populations ure 1). These two lineages of Chordates arose well before the before scientists even have a chance to discover their distri- appearance of jawed fishes. Lampreys and hagfish persisted butions and uniqueness (Carim et al. 2017; Wade et al. 2018). through at least four of five mass extinction events on Earth. Joni Mitchell’s lyrics from “Big Yellow Taxi” seem appropri- How did they survive when most other marine organisms ate here. perished? What does their presence today indicate? “Don’t it always seem to go Studies of evolutionary history tell us that the appear- That you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone ance of the cranium, eyes, pineal gland, inner ear, olfactory They paved paradise rosettes, lateral line, large brain, and muscular heart, were And put up a parking lot” first evident in the lamprey. In fact, the body form of lam- A common genus of lampreys in eastern USA drainages preys is essentially the same as a 360 million-year-old fos- is Ichthyomyzon, which includes six species. Ichthyomyzon sil lamprey (Gess et al. -

Ecology of the River, Brook and Sea Lamprey Lampetra Fluviatilis, Lampetra Planeri and Petromyzon Marinus

Ecology of the River, Brook and Sea Lamprey Lampetra fluviatilis, Lampetra planeri and Petromyzon marinus Conserving Natura 2000 Rivers Ecology Series No. 5 Ecology of the River, Brook and Sea Lamprey Conserving Natura 2000 Rivers Ecology Series No. 5 Peter S Maitland For more information on this document, contact: English Nature Northminster House Peterborough PE1 1UA Tel:+44 (0) 1733 455100 Fax: +44 (0) 1733 455103 This document was produced with the support of the European Commission’s LIFE Nature programme. It was published by Life in UK Rivers, a joint venture involving English Nature (EN), the Countryside Council for Wales (CCW), the Environment Agency (EA), the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH), and the Scotland and Northern Ireland Forum for Environmental Research (SNIFFER). © (Text only) EN, CCW, EA, SEPA, SNH & SNIFFER 2003 ISBN 1 85716 706 6 A full range of Life in UK Rivers publications can be ordered from: The Enquiry Service English Nature Northminster House Peterborough PE1 1UA Email: [email protected] Tel:+44 (0) 1733 455100 Fax: +44 (0) 1733 455103 This document should be cited as: Maitland PS (2003). Ecology of the River, Brook and Sea Lamprey. Conserving Natura 2000 Rivers Ecology Series No. 5. English Nature, Peterborough. Technical Editor: Lynn Parr Series Ecological Coordinator: Ann Skinner Cover design: Coral Design Management, Peterborough. Printed by Astron Document Services, Norwich, on Revive, 75% recycled post-consumer waste paper, Elemental Chlorine Free. 1M. Cover photo: Erling Svensen/UW Photo Ecology of River, Brook and Sea Lamprey Conserving Natura 2000 Rivers This account of the ecology of the river, brook and sea lamprey (Lampetra fluviatilis, L. -

Sea Lampreys Zebra Mussels Asian Carp

Invasive Species Threats to the North American Great Lakes Sea Lampreys Asian Carp What are Sea Lampreys? Zebra Mussels What are Zebra Mussels? What are Asian Carp? •The sea lamprey is an aggressive parasite, equipped with a tooth-filled mouth •The Zebra Mussel is a small non-native mussel originally found in Russia. •The Asian carp is a type of fish that includes four species: black carp, grass carp, that flares open at the end of its body. Sea lampreys are aquatic vertebrates • This animal was transported to North America in the ballast water of a bighead carp, and silver carp. native to the Atlantic Ocean. transatlantic cargo ship and settled into parts of Lake St. Clair. •Adults may be more than 28 kg in weight and 120 cm in length. •Sea lampreys resemble eels, but unlike eels, they feed on large fish. They can •In less than 10 years zebra mussels spread to all five Great Lakes, •Originally, Asian carp were introduced to the United States as a management tool live in both salt and fresh water. Sea lampreys were accidentally introduced into Mississippi, Tennessee, Hudson, and Ohio River Basins. for aqua culture farms and sewage treatment facilities. The carp have made their the Great Lakes in the early 20th century through shipping canals. Today, sea •Many inland waters in Michigan are now infested with Zebra Mussels. way north to the Illinois River after escaping from fish farms during massive lampreys are found in all of the Great Lakes. flooding along the Mississippi River. •Asian carp are a tremendous threat to the Great Lakes and could devastate the Zebra Mussels in the Great Lakes lakes if they enter our Great Lakes ecosystem. -

Jawless Fishes of the World

Jawless Fishes of the World Jawless Fishes of the World: Volume 1 Edited by Alexei Orlov and Richard Beamish Jawless Fishes of the World: Volume 1 Edited by Alexei Orlov and Richard Beamish This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Alexei Orlov, Richard Beamish and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8582-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8582-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Preface ........................................................................................................ ix M. Docker Part 1: Evolution, Phylogeny, Diversity, and Taxonomy Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Molecular Evolution in the Lamprey Genomes and Its Relevance to the Timing of Whole Genome Duplications T. Manousaki, H. Qiu, M. Noro, F. Hildebrand, A. Meyer and S. Kuraku Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 17 Molecular Phylogeny and Speciation of East Asian Lampreys (genus Lethenteron) with reference to their Life-History Diversification Y. Yamazaki and -

The Freshwater Larva of the Primitive Agnathan, Cyclostome Chordate Known As the Sea Lamprey (Petromyzon Marinus) and an Adult Dissection

‘AMMOCOETES’ : the freshwater larva of the primitive Agnathan, Cyclostome Chordate known as the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) and an adult dissection Midsagittal section of lamprey adult Parker TJ, Haswell WA head John E.B. Baker, MIKROGEO Caudal fin 7 mm larva lV Anus & cloaca Oral hood around vestibule & mouth / Brain / Otic capsule / Gill slit / Dorsal fin / Notochord /Dorsal Hollow Nerve Cord Olfactory naris & pit eyes 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Buccal cirri or l ll lll oral papillae endostyle Heart / Liver / Pronephros / Typhlosole in intestine Velum 1-7 are the 7 visceral pouches separated by 8 arches with gill lamellae Oral area Pharynx trunk four cross sections of the Tail ammocoete seen as white dashed lines & roman numerals in the 2nd slide Cartilaginous skeleton of a cyclostome Chondrocranium supporting head & oral funnel apparatus Cartilaginous Branchial basket of adult lamprey Region of cloaca Caudal fin not ochord Dorsal fin cart. Ray- post. Dorsal fin n cart. Ray- ot oc ant. ho rd Pericardial Rasping keratinized tongue cartilage for cutting into body wall of host fish to suck blood & body fluids PROSENCEPHALON Telencephalon Diencephalon (Olfactory) w/ eyes Mesencephalon Pineal or 3rd eye Naris & olfatory sac Rhombencephalon cartilage Eyes, nonfunctional Nasohypophyseal in larvae pouch (‘ant. pituitary’) VELUM hood Buccal cirri or cartilage oral papillae Otic Vesicle – Inner ear Pronephros – dark area around esophagus and above heart Dorsal fin myomeres Spinal cord Notochord Esophagus arch8 Esop hagus Ventricle Atria arch7 Liver Sinus venosus Heart ‘kidney’ Otic Another 7 mm capsule ‘ammocoete’ larva eye Gall bladder cloaca velum eye Pronephros or Gall bladder ‘kidney’ heart esophagus four cross sections of another ammocoete seen as black lines & numerals in the wholemount slide at lower right Post cloacal tail 4 ‘head’ or oral area 1 ‘trunk’ 3 4 3 2 1 Branchial - Pharyngeal region 2 General Circulation: Red = oxygenated blood, Blue = CO2 rich blood Sinus Venosus Anterior Cardinal Vn Posterior Cardinal vn Common Cardinal Vn Dorsal Aorta Caudal Art. -

1 Lamprey (Family Petromyzontidae) Diversity in North Carolina by The

Lamprey (Family Petromyzontidae) Diversity in North Carolina By the NCFishes.com Team In North Carolina, lampreys constitute a small family of very evolutionary primitive fishes. Most people, including fishermen, are not aware of their existence, unless one is fortunate enough to observe a spawning aggregation in the riffles of a clear Mountain or Coastal Plain stream during the late Winter or early Spring or if one has hooked a large gamefish and wondered what sort of critter was attached to it looking like something out of a science fiction movie. Lampreys are eel-like in appearance being slender, slippery, and without scales or jaws. In fact, many people think that’s what they are – some sort of eel. However, lampreys, along with hagfishes, are the most primitive of all fishes, having been around for more than 300 million years. Lampreys range in size from about 100 mm for the smaller Least Brook Lamprey up to 1200 mm (almost 48 inches) and as big around as your fore-arm for fully-grown, adult, Sea Lamprey. In North Carolina, there are only five species (Table 1) which are widely distributed in many Mountain and Coastal Plain basins, but absent from the Piedmont (Maps 1-5) (Tracy et al. 2020). [Please note: Tracy et al. (2020) may be downloaded for free at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings/vol1/iss60/1.] [Note: see Supplemental Maps 1-3 , page 13, showing North Carolina’s 100 counties, 21 river basins, and 4 physiographic regions.] Lampreys are not known to occur in the Savannah, Pigeon, Watauga, or New basins; all other basins are known to have at least one species (Tracy et al. -

Anatomy of the Lamprey

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- ubP lished Research US Geological Survey 2014 Anatomy of the lamprey ear: morphological evidence for occurrence of horizontal semicircular ducts in the labyrinth of Petromyzon marinus Adel Maklad University of Mississippi Medical Center Caitlyn Reed University of Mississippi Medical Center Nicolas Johnson USGS Bernd Fritzsch University of Iowa, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Maklad, Adel; Reed, Caitlyn; Johnson, Nicolas; and Fritzsch, Bernd, "Anatomy of the lamprey ear: morphological evidence for occurrence of horizontal semicircular ducts in the labyrinth of Petromyzon marinus" (2014). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 836. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/836 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- ubP lished Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal of Anatomy J. Anat. (2014) 224, pp432--446 doi: 10.1111/joa.12159 Anatomy of the lamprey ear: morphological evidence for occurrence of horizontal semicircular ducts in the labyrinth of Petromyzon marinus Adel Maklad,1 Caitlyn Reed,1 Nicolas S. Johnson2 and Bernd Fritzsch3 1Department of Neurobiology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA 2Hammond Bay Biological Station, USGS, Great Lakes Science Center, Millersburg, MI, USA 3Department of Biology, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA Abstract In jawed (gnathostome) vertebrates, the inner ears have three semicircular canals arranged orthogonally in the three Cartesian planes: one horizontal (lateral) and two vertical canals. -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences. -

Freshwater Fish – Introduction

Appendix 4, Page 89 Freshwater Fish – Introduction Freshwater fish species play an important role in the social and economic fabric of Alaska. Many are important for subsistence. Recreational and commercial fishing for many species, such as Arctic char, pike, rainbow trout, Dolly Varden, sheefish, and the 5 species of Pacific salmon, account for millions of dollars in commerce annually in Alaska. However, Alaska’s “nongame” fish species—species that are not recreationally or commercially harvested—play a crucial role in aquatic ecosystems and, through predation by terrestrial, avian, and marine species, in other ecosystems as well. Some freshwater fish species constitute an important element of the food chain for many other species including species of potential conservation concern, such as loons and beluga whales. In April 2004, ADF&G convened a diverse group of freshwater fish experts and asked these scientists to develop a short list of species and/or species groups to feature in the CWCS, including specific conservation actions that could be started in the next decade. The group reviewed a complete list of freshwater and anadromous candidate species that excluded species routinely harvested in sport or commercial fisheries in Alaska. By mutual agreement, the group then excluded species (e.g., sturgeon) that occur only incidentally in Alaska. The experts compared the status of the remaining 25 species against 15 criteria; these included the 11 “species selection criteria” listed in Section II(D), plus other criteria the group generated, including whether a species is used by humans, is important prey for another “at-risk” species, or is of demonstrated special scientific importance.