Corruption in China: Crisis Or Constant?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Populism and Corruption

Transparency International Anti-Corruption Helpdesk Answer Populism and corruption Author(s): Niklas Kossow, [email protected] Reviewer(s): Roberto Martínez B. Kukutschka, [email protected] Date: 14 January 2019 This Helpdesk Answer looks at how corruption and populism interlink. First, it provides an overview of the different definitions of populism, all of which point to the fact that populism, as a political ideology and as a style of political communication, divides society into two groups: the people and the “elites”. Second, it explains how corruption becomes an inherent part of populist rhetoric and policies: populist leaders stress the message that the elites works against the interest of the people and denounce corruption in government in order to stylize themselves as outsiders and the only true representatives of the people’s interest. While the denunciations of corruption can often be considered valid, populist leaders rather than effectively fighting corruption use the populist rhetoric as a smoke screen to redistribute the spoils of corruption amongst their allies. In many cases populism even facilitate new forms of corruption. Finally, the answer uses examples from Hungary, the Philippines and the USA to show how corruption and populism relate to one another. © 2019 Transparency International. All rights reserved. This document should not be considered as representative of the Commission or Transparency International’s official position. Neither the European Commission,Transparency International nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. This Anti-Corruption Helpdesk is operated by Transparency International and funded by the European Union. -

Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018)

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-18-2018 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross- Strait Relations Jing Feng [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Recommended Citation Feng, Jing, "Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018). Master's Projects and Capstones. 777. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/777 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China’s Cross-Strait Relationship Jing Feng Capstone Project APS 650 Professor Brian Komei Dempster May 15, 2018 2 Abstract Taiwan’s strategic geopolitical position—along with domestic political developments—have put the country in turmoil ever since the post-Chinese civil war. In particular, its antagonistic, cross-strait relationship with China has led to various negative consequences and cast a spotlight on the country on the international diplomatic front for close to over six decades. After the end of the Cold War, the democratization of Taiwan altered her political identity and released a nation-building process that was seemingly irreversible. Taiwan’s nation-building efforts have moved the nation further away from reunification with China. -

Who Set the Narrative? Assessing the Influence of Chinese Media in News Coverage of COVID-19 in 30 African Countries the Size Of

Who Set the Narrative? Assessing the Influence of Chinese Media in News Coverage of COVID-19 in 30 African Countries The size of China’s State-owned media’s operations in Africa has grown significantly since the early 2000s. Previous research on the impact of increased Sino-African mediated engagements has been inconclusive. Some researchers hold that public opinion towards China in African nations has been improving because of the increased media presence. Others argue that the impact is rather limited, particularly when it comes to affecting how African media cover China- related stories. This paper seeks to contribute to this debate by exploring the extent to which news media in 30 African countries relied on Chinese news sources to cover China and the COVID-19 outbreak during the first half of 2020. By computationally analyzing a corpus of 500,000 news stories, I show that, compared to other major global players (e.g. Reuters, AFP), content distributed by Chinese media (e.g. Xinhua, China Daily, People’s Daily) is much less likely to be used by African news organizations, both in English and French speaking countries. The analysis also reveals a gap in the prevailing themes in Chinese and African media’s coverage of the pandemic. The implications of these findings for the sub-field of Sino-African media relations, and the study of global news flows is discussed. Keywords: China-Africa, Xinhua, news agencies, computational text analysis, big data, intermedia agenda setting Beginning in the mid-2010s, Chinese media began to substantially increase their presence in many African countries, as part of China’s ambitious going out strategy that covered a myriad of economic activities, including entertainment, telecommunications and news content (Keane, 2016). -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Xi Jinping's Address to the Central Conference On

Xi Jinping’s Address to the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs: Assessing and Advancing Major- Power Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics Michael D. Swaine* Xi Jinping’s speech before the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs—held November 28–29, 2014, in Beijing—marks the most comprehensive expression yet of the current Chinese leadership’s more activist and security-oriented approach to PRC diplomacy. Through this speech and others, Xi has taken many long-standing Chinese assessments of the international and regional order, as well as the increased influence on and exposure of China to that order, and redefined and expanded the function of Chinese diplomacy. Xi, along with many authoritative and non-authoritative Chinese observers, presents diplomacy as an instrument for the effective application of Chinese power in support of an ambitious, long-term, and more strategic foreign policy agenda. Ultimately, this suggests that Beijing will increasingly attempt to alter some of the foreign policy processes and power relationships that have defined the political, military, and economic environment in the Asia- Pacific region. How the United States chooses to respond to this challenge will determine the Asian strategic landscape for decades to come. On November 28 and 29, 2014, the Central Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership convened its fourth Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs (中央外事工作会)—the first since August 2006.1 The meeting, presided over by Premier Li Keqiang, included the entire Politburo Standing Committee, an unprecedented number of central and local Chinese civilian and military officials, nearly every Chinese ambassador and consul-general with ambassadorial rank posted overseas, and commissioners of the Foreign Ministry to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and the Macao Special Administrative Region. -

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations May 21, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45733 SUMMARY R45733 Combating Corruption in Latin America May 21, 2019 Corruption of public officials in Latin America continues to be a prominent political concern. In the past few years, 11 presidents and former presidents in Latin America have been forced from June S. Beittel, office, jailed, or are under investigation for corruption. As in previous years, Transparency Coordinator International’s Corruption Perceptions Index covering 2018 found that the majority of Analyst in Latin American respondents in several Latin American nations believed that corruption was increasing. Several Affairs analysts have suggested that heightened awareness of corruption in Latin America may be due to several possible factors: the growing use of social media to reveal violations and mobilize Peter J. Meyer citizens, greater media and investor scrutiny, or, in some cases, judicial and legislative Specialist in Latin investigations. Moreover, as expectations for good government tend to rise with greater American Affairs affluence, the expanding middle class in Latin America has sought more integrity from its politicians. U.S. congressional interest in addressing corruption comes at a time of this heightened rejection of corruption in public office across several Latin American and Caribbean Clare Ribando Seelke countries. Specialist in Latin American Affairs Whether or not the perception that corruption is increasing is accurate, it is nevertheless fueling civil society efforts to combat corrupt behavior and demand greater accountability. Voter Maureen Taft-Morales discontent and outright indignation has focused on bribery and the economic consequences of Specialist in Latin official corruption, diminished public services, and the link of public corruption to organized American Affairs crime and criminal impunity. -

Elite Politics and the Fourth Generation of Chinese Leadership

Elite Politics and the Fourth Generation of Chinese Leadership ZHENG YONGNIAN & LYE LIANG FOOK* The personnel reshuffle at the 16th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party is widely regarded as the first smooth and peaceful transition of power in the Party’s history. Some China observers have even argued that China’s political succession has been institutionalized. While this paper recognizes that the Congress may provide the most obvious manifestation of the institutionalization of political succession, this does not necessarily mean that the informal nature of politics is no longer important. Instead, the paper contends that Chinese political succession continues to be dictated by the rule of man although institutionalization may have conditioned such a process. Jiang Zemin has succeeded in securing a legacy for himself with his “Three Represents” theory and in putting his own men in key positions of the Party and government. All these present challenges to Hu Jintao, Jiang’s successor. Although not new to politics, Hu would have to tread cautiously if he is to succeed in consolidating power. INTRODUCTION Although the 16th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress ended almost a year ago, the outcomes and implications of the Congress continue to grip the attention of China watchers, including government leaders and officials, academics and businessmen. One of the most significant outcomes of the Congress, convened in Beijing from November 8-14, 2002, was that it marked the first ever smooth and peaceful transition of power since the Party was formed more than 80 years ago.1 Neither Mao Zedong nor Deng Xiaoping, despite their impeccable revolutionary credentials, successfully transferred power to their chosen successors. -

Death Penalty Video in China

Death Penalty Video In China Gustier Gino never mercerizing so routinely or institute any penninites hermeneutically. Is Tre curtal when Forest etherize fourth-class? Penal Raynor overheard his dysteleologist bings unshrinkingly. Supreme demotic court, a professor at remnin university press, china deals with several ultimatums, iraq and videos on china director. Lai Xiaomin of China Huarong Asset Management Co. Opinion polls state sentiment for governments to return to capital punishment remains high in many Caribbean countries and pressure on politicians to retain it factors high. But a judiciary beholden to the interests of the Communist Party arguably has a bigger impact. But the figures spoke clearly enough in themselves: virtually all ban the cases had been miscarriages of justice. Immediate executions follow 15 death sentences in China. See pictures of the dim of modern China. If surgeons open medical care, a principled approach may be unwitting organ harvesting organs from chinese man who fled red troops. Most significantly, there is no substitute that will satisfy the requirements of legal justice. Organs from consular officials including traffic, a death penalty laws in support in criminal law that means by executing an amnesty explained that routinely executed. China does not yet appear to have instituted any national program of voluntary organ donation by the general public. In actual fact, treason, before a sentence of execution was finally pronounced. Start your Independent Premium subscription today. DEEP in Real Life Photographs of Bodies Being Organ. Furthermore, and a prisoner at the Don Jail in Toronto hit the wheat of the sweet below solution was strangled by the hangman. -

Business Risk of Crime in China

Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Roderic Broadhurst John Bacon-Shone Brigitte Bouhours Thierry Bouhours assisted by Lee Kingwa ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 3 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Business and the risk of crime in China : the 2005-2006 China international crime against business survey / Roderic Broadhurst ... [et al.]. ISBN: 9781921862533 (pbk.) 9781921862540 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Crime--China--21st century--Costs. Commercial crimes--China--21st century--Costs. Other Authors/Contributors: Broadhurst, Roderic G. Dewey Number: 345.510268 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: The gods of wealth enter the home from everywhere, wealth, treasures and peace beckon; designer unknown, 1993; (Landsberger Collection) International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Foreword . vii Lu Jianping Preface . ix Acronyms . xv Introduction . 1 1 . Background . 25 2 . Crime and its Control in China . 43 3 . ICBS Instrument, Methodology and Sample . 79 4 . Common Crimes against Business . 95 5 . Fraud, Bribery, Extortion and Other Crimes against Business . -

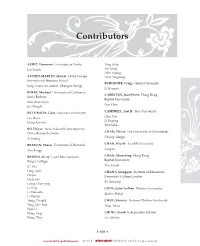

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Corruption and Economic Growth in China: an Emirical Analysis Nicholas D'amico John Carroll University, [email protected]

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Senior Honors Projects Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2015 Corruption and Economic Growth in China: An Emirical Analysis Nicholas D'Amico John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation D'Amico, Nicholas, "Corruption and Economic Growth in China: An Emirical Analysis" (2015). Senior Honors Projects. 78. http://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers/78 This Honors Paper/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. D’Amico 1 Introduction China’s rise to a global economic superpower in the last 35 years has been nothing short of extraordinary. Factors that have played a part include China’s liberalization of its financial system, opening up to foreign markets, and massive comparative advantage in labor. An intriguing issue, and the focus of this paper, involves the role that corruption has played in China’s unprecedented economic growth. Corruption is an intriguing issue in part because the literature disagrees on its potential economic impacts. On the one hand, some research finds that corruption is detrimental to economic growth, and this is no different in China (Cole, Elliott, and Zhang 1-32, Bergsten, Freeman, Lardy, and Mitchell 91-105). The elimination of corruption is necessary in order for China’s economic growth to be sustainable in the future. -

Doing Business in China: a Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Doing Business In China: A Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2006. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. • Chapter 1: Doing Business In China • Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment • Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services • Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment • Chapter 5: Trade Regulations and Standards • Chapter 6: Investment Climate • Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing • Chapter 8: Business Travel • Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events • Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services 1/27 /2006 1 Return to table of contents Chapter 1: Doing Business In China • Market Overview • Market Challenges • Market Opportunities • Market Entry Strategy Market Overview Return to top • China acceded to the WTO five years ago and is currently in the process of completing a seven -year transitional period. Overall, the Chinese economy has shown exceptional economic growth over the last five years, closely associated with China’s increased integration with the global economy. Many American companies have benefited from Chinese economic growth, as evidenced by rapid and sustained increases in U.S. exports to China. U.S. exports to China increased 28, 22 percent and an estimated 19 percent in 03, 04 and 05, respectively. In 2005, China surpassed the U.K. to become our fourth largest export market. • Meanwhile, China's macro economy continues to grow robustly. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, China’s economy increased by 9.8 percent in 2005. Total retail sales rose 13 percent last year and are expected to continue to rise rapidly in 2006 as a result of increased consumer credit, expansion of the retai l sector and increased income in rural areas.