BTI 2018 Country Report Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4-The-Truth-About-Sarawaks-Forest

8/28/2020 The Truth About Sarawak's 'Forest Cover' - Why Shell Should Think Twice Before Engaging With The Timber Crooks | Sarawak Report Secure Key Contact instructions Donate to Sarawak Report Facebook Twitter Sarawak Report Latest Stories Sections Birds Of A Feather Flock Together? "I Am Alright Jack" AKA Najib Razak? Coup Coalition's 1MDB Cover-Up Continues As Talks Confirmed With IPIC GOLF DIPLOMACY AND "BACK-CHANNEL LOBBYING" - US$8 Million To Lobby President Trump, But Najib's Golf Got Cancelled! The Hawaii Connection - How Jho Low Secretly Lobbied Trump For Najib Over 1MDB! 'Back To Normal' With The Same Tired Tricksters And Their Same Old Playbook - Of Sex, Lies and Videotape Stories Talkbacks Campaign Platform Speaker's Corner Press About Sarawak Report Tweet https://www.sarawakreport.org/2019/06/the-truth-about-sarawaks-forest-cover-why-shell-should-think-before-engaging-with-the-timber-crooks/ 1/5 8/28/2020 The Truth About Sarawak's 'Forest Cover' - Why Shell Should Think Twice Before Engaging With The Timber Crooks | Sarawak Report The Truth About Sarawak's 'Forest Cover' - Why Shell Should Think Twice Before Engaging With The Timber Crooks 16 June 2019 Looking for all the world like a gruesome bunch of mafia dons, the head honchos of Sarawak dressed casual this weekend and waddled out to some turf to grin for their favourite PR organ, the Borneo Post (owned by the timber barons of KTS) in order to proclaim their belated attempt to get onto the tree planting band-waggon. The broad face of the mysteriously wealthy deputy chief minister, Awang Tengah dominated the shot (his earlier positions included chairman and director of the Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation and minister of Urban Development and Natural Resources). -

Trends in Southeast Asia

ISSN 0219-3213 2017 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia PARTI AMANAH NEGARA IN JOHOR: BIRTH, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS WAN SAIFUL WAN JAN TRS9/17s ISBN 978-981-4786-44-7 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 789814 786447 Trends in Southeast Asia 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 1 15/8/17 8:38 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and the Singapore APEC Study Centre. ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 2 15/8/17 8:38 AM 2017 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia PARTI AMANAH NEGARA IN JOHOR: BIRTH, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS WAN SAIFUL WAN JAN 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 3 15/8/17 8:38 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2017 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Bernama 27/03/2019

LIMA19 : 40 sophisticated ships anchor in Langkawi waters BERNAMA 27/03/2019 LANGKAWI, March 27 (Bernama) -- A parade of 40 local and international ships anchoring off Langkawi in conjunction with the 2019 Langkawi International Maritime and Aerospace Exhibition (LIMA ‘19) was very hypnotising and attracted the attention of the government administration’s delegation headed by Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad. Dr Mahathir and his delegation were taken aboard KD Perantau belonging to the Royal Malaysian Navy for an hour-and-a-half and received the salutes from the crew of all the ships at Resorts World Langkawi here at the exhibition which was entering its second day today. Among the federal and state government delegates were the Minister of Defence Mohamad Sabu, Economic Affairs Minister Datuk Seri Mohamed Azmin Ali, Transport Minister Anthony Loke, Deputy Minister of Home Affairs Datuk Mohd Azis Jamman and Menteri Besar of Kedah Datuk Seri Mukhriz Mahathir. They were all given the honour of seeing for themselves the greatness and sophistication of the ships, namely, 17 Royal Malaysian Navy ships, five Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) ships, MV Polaris from the Marine Department Malaysia, RV Discovery from Universiti Malaysia Terengganu and 16 ships from 12 countries involved in the event. The 15th edition saw LIMA hosting commercial delegates from 32 countries and 406 defence and commercial companies with 200 international businesses. All their products and services would be exhibited during the five-day event, until March 30 at the Mahsuri International Exhibition Centre (MIEC) and Resort World Langkawi (RWL). About 42,000 commercial visitors were expected to gather at LIMA ‘19, not only to see the latest products and services offered by the participants of the exhibition but also to explore the business potentials especially with companies based in Malaysia. -

Another PAS Leader Quits Penang Gov't Malaysiakini.Com Jun 11, 2015 by Low Chia Ming

Another PAS leader quits Penang gov't MalaysiaKini.com Jun 11, 2015 By Low Chia Ming Another PAS leader has quit his government related posts in Penang, following in the footsteps of the party's ousted progressive leaders, Mohamad Sabu and Mujahid Yusof Rawa. Penang PAS information chief Rosidi Hussain resigned as a director of Penang Youth Development Corporation. This was announced by Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng in a statement today. When contacted, Rosidi said he was resigning to focus on his law firm as a practising lawyer. Rosidi did not want to elaborate further if his resignation had anything to do with PAS under its new conservative hardline leadership passing a resolution to sever ties with DAP. However, he admitted that it was difficult to carry out his duties in the Penang government what with the ongoing spat between PAS and DAP. "But I appreciate the working experience with the chief minister and the state government. "It's just the environment is no longer conducive for me to serve the people as many things are happening," he said. He lamented that the tense relationship between DAP and PAS was a foregone conclusion after they fell into Umno's trap to break up Pakatan Rakyat. Lim (photo) also confirmed receiving Mohamad's resignation as a director of PBA Holdings Berhad. He praised the leaders for their principled stance which he said was in contrast to other PAS representatives who were still clinging on to their government positions even though the party had severed ties with DAP. "Fortunately there are still honourable PAS leaders who have resigned despite the refusal of the PAS new leadership to follow up on their killing Pakatan. -

The Taib Timber Mafia

The Taib Timber Mafia Facts and Figures on Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) from Sarawak, Malaysia 20 September 2012 Bruno Manser Fund - The Taib Timber Mafia Contents Sarawak, an environmental crime hotspot ................................................................................. 4 1. The “Stop Timber Corruption” Campaign ............................................................................... 5 2. The aim of this report .............................................................................................................. 5 3. Sources used for this report .................................................................................................... 6 4. Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 6 5. What is a “PEP”? ....................................................................................................................... 7 6. Specific due diligence requirements for financial service providers when dealing with PEPs ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 7. The Taib Family ....................................................................................................................... 9 8. Taib’s modus operandi ............................................................................................................ 9 9. Portraits of individual Taib family members ........................................................................ -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Sektor Pelancongan Anggar Rugi RM105 Juta, Sektor Perniagaan

Amanah: Anwar’s ‘wise decision’ reflects need to remove distractions Malaysia Today June 18, 2017 By Vanesha Shurentheran Salahuddin Ayub says he shares Anwar’s concern that PPBM’s proposition to occupy top two posts in Pakatan Harapan was worrying. PETALING JAYA: Amanah has lauded Anwar Ibrahim’s move not to offer himself as Pakatan Harapan’s (PH) prime ministerial candidate for the 14th general election (GE14), saying it showed the PKR de facto leader’s determination to remove distractions coming in the path of defeating the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN). Its deputy president Salahuddin Ayub said it was a wise decision as the opposition coalition needs to move forward instead of being weighed down by issues over who should be the prime minister if it wins the election due by the middle of next year. He said Anwar knows what is best for PH in any situation, including the recent scenario where PPBM apparently wanted to lead the coalition. “He has shed light on this for us, for PH to move forward and to forget about who will be the next prime minister,” Salahuddin told FMT. He said it is time for PH component parties to show their strength in unity and convince the people of their cooperation and capabilities. He also said he concurred with Anwar’s concern that PPBM’s proposition was worrying. Salahuddin said it was time for differences in the coalition to be set aside for the sake of the people. “We need to put aside all our differences and advance forward. The people want to know what we can offer to solve their problems,” he said. -

The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds

Seattle Pacific University Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring 6-7-2021 The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds Chea-Mun Tan Seattle Pacific University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Economics Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Tan, Chea-Mun, "The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds" (2021). Honors Projects. 131. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/131 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia’s 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds by Chea-Mun Tan First Reader, Dr. Doug Downing Second Reader, Dr. Hau Nguyen A project submitted in partial fulfillMent of the requireMents of the University Scholars Honors Project Seattle Pacific University 2021 Tan 2 Abstract In 2015, the former PriMe Minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak, was accused of corruption, eMbezzleMent, and fraud of over $700 million USD. Low Taek Jho, the former financier of Malaysia, was also accused and dubbed the ‘mastermind’ of the 1MDB scandal. As one of the world’s largest financial scandals, this paper seeks to explore the political and economic iMplications of 1MDB through historical context and a critical assessMent of governance. Specifically, it will exaMine the economic and political agendas of former PriMe Ministers Najib Razak and Mahathir MohaMad. -

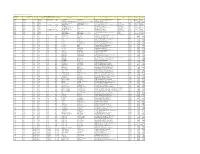

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

1 Orang Asli and Melayu Relations

1 Orang Asli and Melayu Relations: A Cross-Border Perspective (paper presented to the Second International Symposium of Jurnal Antropologi Indonesia, Padang, July 18-21, 2001) By Leonard Y. Andaya In present-day Malaysia the dominant ethnicity is the Melayu (Malay), followed numerically by the Chinese and the Indians. A very small percentage comprises a group of separate ethnicities that have been clustered together by a Malaysian government statute of 1960 under the generalized name of Orang Asli (the Original People). Among the “Orang Asli” themselves, however, they apply names usually associated with their specific area or by the generalized name meaning “human being”. In the literature the Orang Asli are divided into three groups: The Semang or Negrito, the Senoi, and the Orang Asli Melayu.1 Among the “Orang Asli”, however, the major distinction is between themselves and the outside world, and they would very likely second the sentiments of the Orang Asli and Orang Laut (Sea People) in Johor who regard themselves as “leaves of the same tree”.2 Today the Semang live in the coastal foothills and inland river valleys of Perak, interior Pahang, and Ulu (upriver) Kelantan, and rarely occupy lands above 1000 meters in elevation. But in the early twentieth century, Schebesta commented that the areas regarded as Negrito country included lands from Chaiya and Ulu Patani (Singora and Patthalung) to Kedah and to mid-Perak and northern Pahang.3 Most now live on the fringes rather than in the deep jungle itself, and maintain links with Malay farmers and Chinese shopkeepers. In the past they appear to have also frequented the coasts. -

Mw Singapore

VOLUME 4, ISSUE 2 JUNE – DECEMBER 2018 MW SINGAPORE NEWSLETTER OF THE HIGH COMMISSION OF MALAYSIA IN SINGAPORE OFFICIAL VISIT OF PRIME MINISTER YAB TUN DR MAHATHIR MOHAMAD TO SINGAPORE SINGAPORE, NOV 12: YAB Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad undertook an official visit to Singapore, at the invitation of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Singapore, His Excellency Lee Hsien Loong from 12 to 13 November 2018, followed by YAB Prime Minister’s participation at the 33rd ASEAN Summit and Relat- ed Summits from 13 to 15 November 2018. The official visit was part of YAB Prime Minister’s high-level introductory visits to ASEAN countries after being sworn in as the 7th Prime Minister of Malaysia. YAB Tun Dr Mahathir was accompanied by his wife YABhg Tun Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali; Foreign Minister YB Dato’ Saifuddin Abdullah; Minister of Economic Affairs YB Dato’ Seri Mohamed Azmin Ali and senior offi- cials from the Prime Minister’s Office as well as Wisma Putra. YAB Prime Minister’s official programme at the Istana include the Welcome Ceremony (inspection of the Guards of Honour), courtesy call on President Halimah Yacob, four-eyed meeting with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong which was followed by a Delegation Meeting, Orchid-Naming ceremony i.e. an orchid was named Dendrobium Mahathir Siti Hasmah in honour of YAB Prime Minister and YABhg. Tun Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali, of which the pro- grammes ended with an official lunch hosted by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Mrs Lee. During his visit, YAB Prime Minister also met with the members of Malaysian diaspora in Singapore. -

5127 RM4.00 2011:Vol.31No.3 For

Aliran Monthly : Vol.31(3) Page 1 For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity PP3739/12/2011(026665) ISSN 0127 - 5127 RM4.00 2011:Vol.31No.3 COVER STORY Making sense of the forthcoming Sarawak state elections Will electoral dynamics in the polls sway to the advantage of the opposition or the BN? by Faisal S. Hazis n the run-up to the 10th all 15 Chinese-majority seats, spirit of their supporters. As III Sarawak state elections, which are being touted to swing contending parties in the com- II many political analysts to the opposition. Pakatan Rakyat ing elections, both sides will not have predicted that the (PR) leaders, on the other hand, want to enter the fray with the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) will believe that they can topple the BN mentality of a loser. So this secure a two-third majority win government by winning more brings us to the prediction made (47 seats). It is likely that the coa- than 40 seats despite the opposi- by political analysts who are ei- lition is set to lose more seats com- tion parties’ overlapping seat ther trained political scientists pared to 2006. The BN and claims. Which one will be the or self-proclaimed political ob- Pakatan Rakyat (PR) leaders, on likely outcome of the forthcoming servers. Observations made by the other hand, have given two Sarawak elections? these analysts seem to represent contrasting forecasts which of the general sentiment on the course depict their respective po- Psy-war versus facts ground but they fail to take into litical bias. Sarawak United consideration the electoral dy- People’s Party (SUPP) president Obviously leaders from both po- namics of the impending elec- Dr George Chan believes that the litical divides have been engag- tions.