2021 African American Booklist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School of Drama 2020–2021

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Drama 2020–2021 School of Drama 2020–2021 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 116 Number 13 August 30, 2020 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 116 Number 13 August 30, 2020 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in October; three times in September; four and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively times in June and July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney Avenue, New seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Haven CT 06510. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Senior Direc- tor of the O∞ce of Institutional Equity and Access, 221 Whitney Avenue, 4th Floor, The closing date for material in this bulletin was July 30, 2020. -

Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack

Originating on WMNR Fine Arts Radio [email protected] Playlist* Program is archived 24-48 hours after broadcast and can be heard Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack free of charge at Public Radio Exchange, > prx.org > Broadway Bound *Playlist is listed alphabetically by show (disc) title, not in order of play. Show #: 269 Broadcast Date: May 27, 2017 Time: 16:00 - 18:00 # Selections: 27 Time Writer(s) Title Artist Disc Label Year Position Comment File Number Intro Track Holiday Release Date Date Played Date Played Copy 3:24 Menken|Ashman|Rice|Beguelin Somebody's Got Your Back James Monroe Iglehart, Adam Jacobs & Aladdin Original Broadway Cast Disney 2014 Opened 3/20/2014 CDS Aladdin 15 2014 8/16/14 12/6/14 1/7/17 5/27/17 3:17 Irving Berlin Anything You Can Do Bernadette“friends” Peters and Tom Wopat Annie Get Your Gun - New Broadway Cast Broadway Angel 1999 3/4/1999 - 9/1/2001. 1045 perf. 2 Tony Awards: Best Revival. Best Actress, CDS Anni none 18 1999 6/7/08 5/27/17 Bernadette Peters. 3:30 Cole Porter Friendship Joel Grey, Sutton Foster Anything Goes - New Broadway Cast 2011 Ghostlight 2011 Opened 4/7/11 at the Stephen Sondheim Theater. THREE 2011 Tony Awards: Best Revival CDS Anything none 9 2011 12/10/113/31/12 5/27/17 of a Musical; Best Actress in a Musical: Sutton Foster; Best Choreography: Kathleen 2:50 John Kander/Fred Ebb Two Ladies Alan Cumming, Erin Hill & Michael Cabaret: The New Broadway Cast Recording RCA Victor 1998 3/19/1998 - 1/4/2004. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

Want to Start a Revolution? Gore, Dayo, Theoharis, Jeanne, Woodard, Komozi

Want to Start a Revolution? Gore, Dayo, Theoharis, Jeanne, Woodard, Komozi Published by NYU Press Gore, Dayo & Theoharis, Jeanne & Woodard, Komozi. Want to Start a Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: NYU Press, 2009. Project MUSE., https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/10942 Access provided by The College Of Wooster (14 Jan 2019 17:31 GMT) 4 Shirley Graham Du Bois Portrait of the Black Woman Artist as a Revolutionary Gerald Horne and Margaret Stevens Shirley Graham Du Bois pulled Malcolm X aside at a party in the Chinese embassy in Accra, Ghana, in 1964, only months after hav- ing met with him at Hotel Omar Khayyam in Cairo, Egypt.1 When she spotted him at the embassy, she “immediately . guided him to a corner where they sat” and talked for “nearly an hour.” Afterward, she declared proudly, “This man is brilliant. I am taking him for my son. He must meet Kwame [Nkrumah]. They have too much in common not to meet.”2 She personally saw to it that they did. In Ghana during the 1960s, Black Nationalists, Pan-Africanists, and Marxists from around the world mingled in many of the same circles. Graham Du Bois figured prominently in this diverse—sometimes at odds—assemblage. On the personal level she informally adopted several “sons” of Pan-Africanism such as Malcolm X, Kwame Nkrumah, and Stokely Carmichael. On the political level she was a living personification of the “motherland” in the political consciousness of a considerable num- ber of African Americans engaged in the Black Power movement. -

PSC-CUNY Research Awards (Traditional A)

PSC-CUNY Research Awards (Traditional A) Control No: TRADA-42-229 Name : Willinger, David Rank: Professor Address : Tenured: Yes Telephone : College: CITY COLLEGE Email: Panel: Performing Arts Performing Arts Discipline : Scholarship Human Subject Use No Animal Subject Use No Supplementary Materials No List of Supplementary Material Department THEATER Title of Proposed Project: IVO VAN HOVE: A MAJOR THEATRE ARTIST AND HIS WORK Brief Abstract This is a proposal for a major book-length retrospective study of Ivo Van Hove’s career as a theatre director. It would take on his design innovations and his revolutionary approach to text and theatrical ambiance as well as chart the relationships with specific theatres and theatre companies of this, one of the most prominent theatre iconoclasts alive today. Van Hove is particularly important in that he acts as one of the few long-time “bridges” between European and American praxis. His career, in itself, represents a model of cross-fertilization, as he has brought European radical interpretation of classics to America and American organic acting to Europe. This book, as conceived would contain a generous number of images illustrating his productions and archive a wide cross-section of critical and analytical responses that have engaged in the controversies his work has engendered, as well as posit new, overarching hypotheses. Relevant Publications PUBLICATIONS & Scholarship BOOKS A Maeterlinck Reader (co-edited with Daniel Gerould) New York, Francophone Belgian Series, Peter Lang Publications, 2011 Translations of The Princess Maleine, Pelleas and Melisande, The Intruder, The Blind, The Death of Tintagiles, and numerous essays, with an extensive historical and analytical introduction, 358 pp. -

A History of African American Theatre Errol G

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62472-5 - A History of African American Theatre Errol G. Hill and James V. Hatch Frontmatter More information AHistory of African American Theatre This is the first definitive history of African American theatre. The text embraces awidegeographyinvestigating companies from coast to coast as well as the anglo- phoneCaribbean and African American companies touring Europe, Australia, and Africa. This history represents a catholicity of styles – from African ritual born out of slavery to European forms, from amateur to professional. It covers nearly two and ahalf centuries of black performance and production with issues of gender, class, and race ever in attendance. The volume encompasses aspects of performance such as minstrel, vaudeville, cabaret acts, musicals, and opera. Shows by white playwrights that used black casts, particularly in music and dance, are included, as are produc- tions of western classics and a host of Shakespeare plays. The breadth and vitality of black theatre history, from the individual performance to large-scale company productions, from political nationalism to integration, are conveyed in this volume. errol g. hill was Professor Emeritus at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire before his death in September 2003.Hetaughtat the University of the West Indies and Ibadan University, Nigeria, before taking up a post at Dartmouth in 1968.His publications include The Trinidad Carnival (1972), The Theatre of Black Americans (1980), Shakespeare in Sable (1984), The Jamaican Stage, 1655–1900 (1992), and The Cambridge Guide to African and Caribbean Theatre (with Martin Banham and George Woodyard, 1994); and he was contributing editor of several collections of Caribbean plays. -

PHILANTHROPIST, ENTREPRENEUR and RECORDING ARTIST

THE FLORIDA STAR, NORTHEAST FLORIDA’S OLDEST, LARGEST, MOST READ AFRICAN AMERICAN OWNED NEWSPAPER The Florida Star Presorted Standard P. O. Box 40629 U.S. Postage Paid Jacksonville, FL 32203 Jacksonville, FL Philanthropic Families Donate More Permit No. 3617 Than Half A Million Dollars to Can’t Get to the Store? Bethune-Cookman University Have The Star Delivered! Story on page 6 Read The Florida and Georgia Star THE FLORIDA Newspapers. STAR thefl oridastar.com The only media Listen to IMPACT to receive the Radio Talk Show. Jacksonville Sheriff’s The people’s choice Offi ce Eagle Award for being “The Most Factual.” APRIL 11 - APRIL 17, 2020 VOLUME 69, NUMBER 52 $1.00 Daughter of MLK Named PHILANTHROPIST, to Georgia ENTREPRENEUR and Coronavirus RECORDING ARTIST Outreach Group Keeve Murdered eeve Hikes, Philanthropist, entre- preneur and rapper from Jack- sonville, Florida was fatally shot Tuesday evening. Keeve was pro- nounced dead on the scene, ac- cordingK to offi cials. News of his death, prompted an out- pouring of support from the Jacksonville Florida community. Dr. Bernice King, daughter of civil rights “May His peace comfort you all leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. will help lead a new outreach committee in Georgia during this diffi cult time. His life was a as the state copes with the coronavirus, Gov. Testament of time well spent.” Brian Kemp announced Sunday. Keeve drew attention for industry King, chief executive offi cer of the Martin leaders from his hit single “ Bag” Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social feat. YFN Lucci, from his album en- Change in Atlanta, will co-chair the commit- titled “ No Major Deal But I’m Still tee of more than a dozen business and com- Major”. -

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

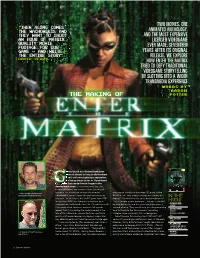

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Freedom Summer

MISSISSIPPI BURNING THE FREEDOM SUMMER OF 1964 Prepared by Glenn Oney For Teaching American History The Situation • According to the Census, 45% of Mississippi's population is Black, but in 1964 less than 5% of Blacks are registered to vote state-wide. • In the rural counties where Blacks are a majority — or even a significant minority — of the population, Black registration is virtually nil. The Situation • For example, in some of the counties where there are Freedom Summer projects (main project town shown in parenthesis): Whites Blacks County (Town) Number Eligible Number Voters Percentage Number Eligible Number Voters Percentage Coahoma (Clarksdale) 5338 4030 73% 14004 1061 8% Holmes (Tchula) 4773 3530 74% 8757 8 - Le Flore (Greenwood) 10274 7168 70% 13567 268 2% Marshall (Holly Spgs) 4342 4162 96% 7168 57 1% Panola (Batesville) 7369 5309 69% 7250 2 - Tallahatchie (Charleston) 5099 4330 85% 6438 5 - Pike (McComb) 12163 7864 65% 6936 150 - Source: 1964 MFDP report derived from court cases and Federal reports. The Situation • To maintain segregation and deny Blacks their citizenship rights — and to continue reaping the economic benefits of racial exploitation — the white power structure has turned Mississippi into a "closed society" ruled by fear from the top down. • Rather than mechanize as other Southern states have done, much of Mississippi agriculture continues to rely on cheap Black labor. • But with the rise of the Freedom Movement, the White Citizens Council is now urging plantation owners to replace Black sharecroppers and farm hands with machines. • This is a deliberate strategy to force Blacks out of the state before they can achieve any share of political power. -

Geffen Lights out Cast FINAL

Media Contact: Zenon Dmytryk Geffen Playhouse [email protected] 310.966.2405 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CAST ANNOUNCED FOR GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE WEST COAST PREMIERE OF LIGHTS OUT: NAT “KING” COLE NOW EXTENDED THROUGH MARCH 17 FEATURING DULÉ HILL AS NAT “KING” COLE ADDITIONAL CAST INCLUDES GISELA ADISA, CONNOR AMACIO MATTHEWS, BRYAN DOBSON, RUBY LEWIS, ZONYA LOVE, MARCIA RODD, BRANDON RUITER AND DANIEL J. WATTS PREVIEWS BEGIN FEBRUARY 5 - OPENING NIGHT IS FEBRUARY 13 LOS ANGELES (December 19, 2018) – Geffen Playhouse today announced the full cast for its production of Lights Out: Nat “King” Cole, written by Tony and Olivier Award nominee Colman Domingo (Summer: The Donna Summer Musical, If Beale Street Could Talk, Fear the Walking Dead) and Patricia McGregor (Place, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Skeleton Crew), directed by Patricia McGregor and featuring Emmy Award nominee Dulé Hill (Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk; The West Wing; Psych) as Nat “King” Cole. This marks the West Coast premiere for the production, which made its world premiere in 2017 at People’s Light, one of Pennsylvania’s largest professional non-profit theaters. Under the auspices of the Geffen Playhouse, the production from People’s Light has been further workshopped, songs have been added and the play has continued to evolve. In addition to Hill, the cast features Gisela Adisa (Beautiful, Sister Act) as Eartha Kitt and others; Connor Amacio Matthews (In the Flow with Connor Amacio) as Billy Preston and others; Bryan Dobson (Jesus Christ Superstar, The Rocky Horror Show) as Producer and others; Ruby Lewis (Marilyn! The New Musical, Jersey Boys) as Betty Hutton, Peggy Lee and others; Zonya Love (Emma and Max, The Color Purple) as Perlina and others; Marcia Rodd (Last of the Red Hot Lovers, Shelter) as Candy and others; Brandon Ruiter (Sex with Strangers, A Picture of Dorian Gray) as Stage Manager and others; and Daniel J. -

The Black Power Movement

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 1: Amiri Baraka from Black Arts to Black Radicalism Editorial Adviser Komozi Woodard Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 1, Amiri Baraka from Black arts to Black radicalism [microform] / editorial adviser, Komozi Woodard; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. p. cm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. ISBN 1-55655-834-1 1. Afro-Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—Sources. 3. Black nationalism—United States— History—20th century—Sources. 4. Baraka, Imamu Amiri, 1934– —Archives. I. Woodard, Komozi. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Lewis, Daniel, 1972– . Guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. IV. Title: Amiri Baraka from black arts to Black radicalism. V. Series. E185.615 323.1'196073'09045—dc21 00-068556 CIP Copyright © 2001 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-834-1. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................