The Dragon and the Crown : Hong Kong Memoirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Existing Services for the English Speaking Children with Special Needs Government Subsidized Programme Private Programme English Kindergartens from E.G

Overview of Existing Services for the English Speaking Children with Special Needs Government Subsidized Programme Private Programme English Kindergartens From e.g. AP, ARN, TCI, Little Kids Learning e.g. Anfield, ESF, Small World Christian, Birth to The Child Development Centre Academy, Kids Connect, Bridge Academy, Woodland, KBCK, Yiu Chung, David Exodus, Int’l Montessori, Safari Kids, Bebegarten, Age of Watchdog Early Education Centre Rainbow Early Intervention Progrmme Kingston, Letterland Childcare Centre, YMCA, 6 KCIS, DBIS, DMK, Tutor Time Int’l, SunIsland, Delia English Kindergarten / Debroah English Kindergarten ESF Special Needs Provisions Other Alternatives Learning Support Classes Segregated •Springboard Project • Island Christian Academy •Bradbury (21) Setting •Family Partners School •The Children Institute of HK (Harbour School) • NIS •Quarry Bay (7) •ICS (Bridges class) •Hong Lok Yuen Int’l School •Peak School (7) • Jockey Club •Aoi Pui School & Autism Partnership •DBIS & DMPS •Glenealy school (7) Sarah Roe •Rainbow Project (HK Island) * • Christian Alliance Int’l School Primary •Kennedy School (7) School (70) •Autism Recovery Network •Kellett School •Bridge Academy Schools •Beacon Hill (21) •Hong Kong Academy • The International Montessori School •Kowloon Junior School •St. Bosco Centre (Anfield School) • Kingston Int’l Primary School •Kids Connect (14) • Woodland Int’l Primary School •Clearwater Bay (7) Local System • Think International School •Shatin Junior School (14) • Japanese International School •Catholic Mission -

2019 Annual Report (8.37MB PDF)

CONTENTS 2 Financial Summary 4 Corporate Information 6 Biographical Details of Directors and Senior Management 13 Abridged Corporate Structure 14 Shareholders’ Calendar 15 Chairman’s Statement 18 Chief Executive’s Statement 33 Directors’ Report 46 Corporate Governance Report 69 Independent Auditor’s Report 74 Financial Statements – Contents 76 Consolidated Income Statement 77 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 78 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 79 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 81 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 83 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 232 Unaudited Supplementary Financial Information 253 Head Office, Branches, Sub-Branches, Representative Office, Principal Subsidiaries and Associates FINANCIAL SUMMARY TOTAL ADVANCES TO CUSTOMERS / TOTAL CUSTOMERS' DEPOSITS / TOTAL ASSETS HK$ Million 250,000 200,000 212,768 190,576 150,000 163,747 162,665 143,690 137,772 127,838 118,759 118,079 100,000 108,046 102,881 101,825 99,392 85,188 82,133 86,698 71,165 70,689 50,000 63,600 56,925 45,120 0 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Total Advances To CustomersTotal Customers’ Deposits Total Assets TOTAL EQUITY HK$ Million 25,000 24,863 22,542 20,000 17,434 15,000 15,914 15,108 10,000 10,784 7,732 5,000 0 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2 Chong Hing Bank Limited FINANCIAL SUMMARY PROFIT ATTRIBUTABLE TO EQUITY OWNERS HK$ Million 3,000 2,742 2,500 2,000 1,901 1,760 1,500 1,565 1,420 1,193 1,000 793 500 557 0 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Profit from the sale of Chong Hing Bank Centre -

Mortgage Corporation 〜The Poison Or

MORTGAGE CORPORATION 〜THE POISON OR MEDICINE TO HONG KONG ECONOMY ? by ’ CHENG LOK-MAN 鄭洛文 MBA PROJECT REPORT Presented to The Graduate School In the Partial Fulfilment ofthe Requirements of the Degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION TWO-YEAR MBA PROGRAMME THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG May 1999 =i^^trjeCr;":fy of Hon^o^g holds the copyr|ght ofthis project. Any person(s) intending to use a part or Gradu^e 8^00^ 口」‘“^ P,osed pubhcat,on must seek copyright release from the Dean of the ^¾ k{ I \ ii • J-| ^P^ APPROVAL Name: Cheng Lok-Man Degree: Master ofBusiness Administration Title of Project: Mortgage Corporation 〜The Poison or Medicine to Hong Kong Economy? 、 丄 Pro$fessp^ Raymondh C.P.ChiaA iCg Date Approved: / ii ABSTRACT In 1997, Hong Kong Mortgage Corporation ("HKMC") has started its operation in Hong Kong. The objective of the corporation is to enhance the home ownership in Hong Kong. This study is to observe the performance ofthe corporation m the past and analyse whether the corporation accomplishes the objectives mentioned. The short history of Hong Kong mortgage market places the obstacle to HKMC in enforcing the mortgage securitization. Different voices from parties reflected the shaping of the "much better,mortgage corporation is needed. On one hand,Fannie Mae, an experienced US mortgage corporation, gives the advice and keeps tracks of the performances of HKMC. On the other hand, the interaction between the parties involved in this game is also the main task force in the process of modification. Suggestions will be given in order to upgrade the quality ofservices ofHKMC and facilitated the pace of maturity of the corporation in future. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

Prospectus E.Pdf

IMPORTANT If you are in any doubt about this prospectus, you should consult your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. (Incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability under the Companies Ordinance) GLOBAL OFFERING Number of Offer Shares in the Global Offering: 2,298,435,000 (subject to adjustment and the Over-allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong OÅer Shares: 229,843,500 (subject to adjustment) Maximum OÅer Price: HK$9.50 per OÅer Share payable in full on application in Hong Kong dollars, subject to refund Nominal Value: HK$5.00 per Share Stock Code: 2388 Joint Global Coordinators and Joint Bookrunners BOC International Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. UBS Warburg Holdings Limited Joint Sponsors BOCI Asia Limited Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. UBS Warburg Asia Limited The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this prospectus. A copy of this prospectus, together with the documents speciÑed in the section headed ""Documents Delivered to the Registrar of Companies'' in Appendix VIII, has been registered by the Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong as required by Section 38D of the Companies Ordinance, Chapter 32 of the Laws of Hong Kong. The Securities and Futures Commission and the Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong take no responsibility as to the contents of this prospectus or any other document referred to above. -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) Ancient Emaki "Genesis" Exploration and Practice of Emaki Art Expression Tong Zhang Digital Media and Design Arts College Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications Beijing, China 100876 Abstract—The ancient myths and legends with distinctive generation creators such as A Gen, sheep and others, and a Chinese characteristics, refers to myths and legends from dedicated serial picture book magazine "Paint Heart", Chinese Xia Dynasty until ancient times, it carries the origin of "STORY" appears, the delicate picture and vivid story make Chinese culture and it is the foundation of the Chinese nation, it Chinese picture book also developing rapidly and has formed a influence the formation and its characteristics of the national national reading faction craze for outstanding picture books. spirit to a large extent. The study explore and practice the art expression which combines ancient culture with full visual 1) Picture book traced back to ancient Chinese Emaki: impact Emaki form, learn traditional Chinese painting China has experienced a few stages include ancient Emaki, techniques and design elements, and strive to make a perfect illustrated book in Republican period and modern picture performance for the magnificent majestic ancient myth with a books. "Picture book", although the term originated in Japan, long Emaki. It provides a fresh visual experience to the readers and promotes the Chinese traditional culture, with a certain but early traceable picture books is in China. In Heian research value. Kamakura Period Japanese brought Buddhist scriptures (Variable graph), Emaki (Lotus Sutra) and other religious Keywords—ancient myths; Emaki form; Chinese element Scriptures as picture books back to Japan, until the end of Middle Ages Emaki had developed into Nara picture books. -

T It W1~~;T~Ril~T,~

University of Hong Kong Libraries Publications, No.7 LIBRARIES AND INFORMATION CENTRES IN HONG KONG t it W1~~;t~RIl~t,~ Compiled and edited by Julia L.Y. Chan ~B~ B.A., M.L.S., A.H.I.P., FHKLA Angela S.W. Van I[I~Uw~ B.A., M.L.S., A.H.I.P., A.A.L.I.A. Kan Lai-bing MBiJl( B.Sc., M.A., M.L.S., Ph.D., Hon. D.Litt, A.L.A.A., M.I.Inf. Sc., FHKLA Published for The Hong Kong Library Association by Hong Kong University Press * 1~ *- If ~ )i[ ltd: Hong Kong University Press 139 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 1996 ISBN 962 209 409 0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in Hong Kong by United League Graphic & Printing Company Limited Contents Plates Preface xv Introduction xvii Abbreviations & Acronyms xix Alphabetical Directory xxi Organization Listings, by Library Types 533 Libraries Open to the Public 535 Post-Secondary College and University Libraries 538 School Libraries 539 Government Departmental Libraries 550 HospitallMedicallNursing Libraries 551 Special Libraries 551 Club/Society Libraries 554 List of Plates University of Hong Kong Main Library wnt**II:;:tFL~@~g University of Hong Kong Main Library - Electronic Infonnation Centre wnt**II:;:ffr~+~~n9=t{., University of Hong Kong Libraries - Chinese Rare Book Room wnt**II:;:i139=t)(~:zjs:.~ University of Hong Kong Libraries - Education -

List of Licensed Banks Which Are Not Currently Issuing and Facilitating The

List of licensed banks which are not currently issuing and facilitating the issue of SVF Licence Effective Date Name of Licenced Bank (in alphabetical order) Address of the Principal Place of Business in Hong Kong Number (dd/mm/yyyy) ABN AMRO BANK N.V. UNITS 7001-06 & 7008B, LEVEL 70, INTERNATIONAL COMMERCE CENTRE, 1 AUSTIN ROAD WEST, KOWLOON, HONG KONG. SVFB299 13/11/2016 AGRICULTURAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED 25/F, AGRICULTURAL BANK OF CHINA TOWER, 50 CONNAUGHT ROAD CENTRAL, HONG KONG. SVFB235 13/11/2016 AIRSTAR BANK LIMITED SUITES 3201-07, TOWER 5, THE GATEWAY, HARBOUR CITY, TSIM SHA TSUI, KOWLOON SVFB329 09/05/2019 ANT BANK (HONG KONG) LIMITED SUITES 2312-13, 23/F, TOWER ONE, TIMES SQUARE, 1 MATHESON STREET, CAUSEWAY BAY, HONG KONG SVFB331 09/05/2019 AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED 22/F, THREE EXCHANGE SQUARE, 8 CONNAUGHT PLACE, CENTRAL, HONG KONG. SVFB164 13/11/2016 BANCO BILBAO VIZCAYA ARGENTARIA S.A. UNIT 9507, LEVEL 95, INTERNATIONAL COMMERCE CENTRE, 1 AUSTIN ROAD WEST, KOWLOON. SVFB157 13/11/2016 BANCO SANTANDER, S.A. 10/F, TWO INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CENTRE, 8 FINANCE STREET, CENTRAL, HONG KONG. SVFB289 13/11/2016 BANGKOK BANK PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED BANGKOK BANK BUILDING, 28 DES VOEUX ROAD, CENTRAL, HONG KONG. SVFB036 13/11/2016 BANK J. SAFRA SARASIN AG 40/F, EDINBURGH TOWER, THE LANDMARK, 15 QUEEN'S ROAD CENTRAL, HONG KONG. SVFB297 13/11/2016 BANK JULIUS BAER & CO. LTD. 39/F, ONE INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CENTRE, 1 HARBOUR VIEW STREET, CENTRAL, HONG KONG. SVFB301 13/11/2016 BANK OF AMERICA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 52/F, CHEUNG KONG CENTER, 2 QUEEN'S ROAD CENTRAL, CENTRAL, HONG KONG. -

Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs Into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.47-86 47 Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8 ∗∗ Nataša VAMPELJ SUHADOLNIK 9 Abstract This paper examines the ways in which Fuxi and Nüwa were depicted inside the mu- ral tombs of the Wei-Jin dynasties along the Hexi Corridor as compared to their Han counterparts from the Central Plains. Pursuing typological, stylistic, and iconographic approaches, it investigates how the western periphery inherited the knowledge of the divine pair and further discusses the transition of the iconographic and stylistic design of both deities from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) to the Wei and Western Jin dynasties (220–316). Furthermore, examining the origins of the migrants on the basis of historical records, it also attempts to discuss the possible regional connections and migration from different parts of the Chinese central territory to the western periphery. On the basis of these approaches, it reveals that the depiction of Fuxi and Nüwa in Gansu area was modelled on the Shandong regional pattern and further evolved into a unique pattern formed by an iconographic conglomeration of all attributes and other physical characteristics. Accordingly, the Shandong region style not only spread to surrounding areas in the central Chinese territory but even to the more remote border regions, where it became the model for funerary art motifs. Key Words: Fuxi, Nüwa, the sun, the moon, a try square, a pair of compasses, Han Dynasty, Wei-Jin period, Shandong, migration Prenos slikovnih motivov na zahodno periferijo: Fuxi in Nüwa v grobnicah s poslikavo iz obdobja Wei Jin na območju prehoda Hexi Izvleček Pričujoči prispevek v primerjalni perspektivi obravnava upodobitev Fuxija in Nüwe v grobnicah s poslikavo iz časa dinastij Wei in Zahodni Jin (220–316) iz province Gansu * The author acknowledges the financial support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) in the framework of the research core funding Asian languages and Cultures (P6-0243). -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

SAP Crystal Reports

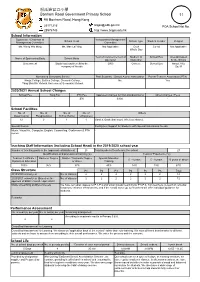

般咸道官立小學 Bonham Road Government Primary School 11 9A Bonham Road, Hong Kong 25171216 [email protected] POA School Net No. 28576743 http://www.brgps.edu.hk School Information Supervisor / Chairman of Incorporated Management School Head School Type Student Gender Religion Management Committee Committee Ms. Wong Wai Ming Ms. Man Lai Ying Not Applicable Gov't Co-ed Not Applicable Whole Day Year of Commencement of Medium of School Bus Area Occupied Name of Sponsoring Body School Motto Operation Instruction by the School Government Study hard and benefit by the 2000 Chinese School Bus About 3765 company of friends Sq. M Nominated Secondary School Past Students' / School Alumni Association Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) King's College, Belilios College, Clementi College, No Yes Tang Shiu Kin Victoria Government Secondary School 2020/2021 Annual School Charges School Fee Tong Fai PTA Fee Approved Charges for Non-standard Items Other Charges / Fees - - $70 $300 - School Facilities No. of No. of No. of No. of Others Classroom(s) Playground(s) School Hall(s) Library(ies) 12 2 1 1 Garden, Basketball court, Wireless intranet. Special Rooms Facility(ies) Support for Students with Special Educational Needs Music, Visual Art, Computer, English, Counselling, Conference & PTA - rooms. Teaching Staff Information (including School Head) in the 2019/2020 school year Number of teaching posts in the approved establishment 25 Total number of teachers in the school 27 Qualifications and professional training (%) Years of Experience (%) Teacher Certificate / Bachelor Degree Master / Doctorate Degree Special Education 0 - 4 years 5 - 9 years 10 years or above Diploma in Education or above Training 100% 96% 33% 40% 14% 19% 67% Class Structure P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 P6 Total 2019/2020 school year No.