Classic Media Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Ii

The Ferris FCC: Forging a new coalition Broadcasting'he newsweekly of broadcasting and allied arts Our 47th ii Dec Year 1977 - yewltness ews is # - in all 43 Arbitron demos.` .and #1 in 45 Nielsen demos (with one tie), again dominating the Twin Cities' news at 10 p.m.** Our news at 6 p.m. also led the field, winning 36 out of 43 Arbitron demos and tieing 5'. That's news dominance! To you it means that KSTP -TV is your best news choice for reaching people of all walks of life and of all ages. (For example, we deliver more than twice as many 18 -49 TSA adults as our closest competitor*.) Go with the clean -sweep channel: KSTP -TV. m Source: `Arbitron / "Nielsen, October 1977, program audiences, 7-day averages. Estimates subject to limitation in said reports. V J I 'i I r I I Ì I I i --- '---- - The most extraordinary serie access time. The pilc late in 1977and early 197 and to be telecast b New York WABC-TV Baltimore WBAL -TV Orlando/ Los Angeles KABC-TV Portland, OR KATU Daytona Beach WDBO -1 Chicago WLS-TV Denver KMGH -TV Albany /Schenectady WRC Philadelphia KYW-TV Cincinnati WCPO -TV Syracuse WT\ Boston WCVB-TV Sacramento /Stockton KXTV Dayton W H I O -1 San Francisco/ Milwaukee WITI-TV San Antonio KSAT-1 Oakland KGO-TV Kansas City KCMO-TV Charleston/ Detroit WXYZ-TV Nashville WNGE Huntington WSAZ -1 Washington, DC WJLA-TV Providence WJAR-TV Salt Lake City KSL -1 Cleveland WEWS San Diego KGTV Winston -Salem/ Pittsburgh KDKA-TV Phoenix KTAR-TV Greensboro WXII -1 Dallas/Ft. -

Cartersville

Sunday Edition September 22, 2019 BARTOW COUNTY’S ONLY DAILY NEWSPAPER $1.50 City of Adairsville mulling tighter Cartersville City Council restrictions on vaping, CBD shops tables BY JAMES SWIFT “The purpose behind this is there is a sig- [email protected] nifi cant question in state law and federal law decision on regarding the THC oil, CBD products and vap- Earlier this month, the Adairsville City ing-type products,” said attorney Bobby Walk- Center Road Council unanimously approved a resolution es- er. “The Federal Drug Administration, as we tablishing an “emergency moratorium” on the speak, is considering a potential ban of fl avored apartments for operation of any new businesses “substantial- oils for e-cigarettes, there’s been a number of ly engaged in the sale of low-THC oil, tobacco state laws passed dealing with this … what this three months products, tobacco-related objects, alternative would do is place a moratorium on any new nicotine products, vapor products, cannabidiol businesses opening that engage and sell in these BY JAMES SWIFT (CBD) and products containing cannabidiol.” types of materials, or rather, substantially en- [email protected] JAMES SWIFT/THE DAILY TRIBUNE NEWS According to legal counsel for the munici- gaged in selling this type of material.” Adairsville Community Development Director Richard Osborne pality, the moratorium will be in effect for 150 The Cartersville City Council speaks at Monday’s Unifi ed Zoning Board meeting. days, dating back to Sept. 12. SEE ADAIRSVILLE, PAGE 2A was set to hear the fi rst reading of a rezoning request that would allow a developer to begin the groundwork on a proposed 300- unit apartment complex off Cen- ter Road at Thursday morning’s Bartow’s public meeting. -

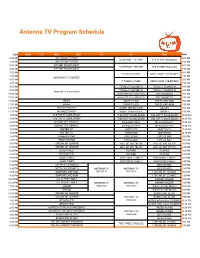

Antenna TV Program Schedule

Antenna TV Program Schedule East MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN West 5:00 AM BACHELOR FATHER 2:00 AM SUSPENSE THEATRE THE THREE STOOGES 5:30 AM BACHELOR FATHER 2:30 AM 6:00 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST 3:00 AM SUSPENSE THEATRE THE THREE STOOGES 6:30 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST 3:30 AM 7:00 AM 4:00 AM IT TAKES A THIEF HERE COME THE BRIDES 7:30 AM 4:30 AM ANTENNA TV THEATER 8:00 AM 5:00 AM IT TAKES A THIEF HERE COME THE BRIDES 8:30 AM 5:30 AM 9:00 AM TOTALLY TOONED IN TOTALLY TOONED IN 6:00 AM 9:30 AM TOTALLY TOONED IN TOTALLY TOONED IN 6:30 AM ANTENNA TV THEATER 10:00 AM ANIMAL RESCUE CLASSICS (E/I) THE MONKEES 7:00 AM 10:30 AM ANIMAL RESCUE CLASSICS (E/I) THE MONKEES 7:30 AM 11:00 AM HAZEL SWAP TV (E/I) THE FLYING NUN 8:00 AM 11:30 AM HAZEL SWAP TV (E/I) THE FLYING NUN 8:30 AM 12:00 PM MCHALE'S NAVY WORD TRAVELS (E/I) GIDGET 9:00 AM 12:30 PM MCHALE'S NAVY WORD TRAVELS (E/I) GIDGET 9:30 AM 1:00 PM THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW 10:00 AM 1:30 PM THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW 10:30 AM 2:00 PM DENNIS THE MENACE MCHALE'S NAVY MCHALE'S NAVY 11:00 AM 2:30 PM DENNIS THE MENACE MCHALE'S NAVY MCHALE'S NAVY 11:30 AM 3:00 PM MISTER ED MISTER ED MISTER ED 12:00 PM 3:30 PM MISTER ED MISTER ED MISTER ED 12:30 PM 4:00 PM GREEN ACRES CIRCUS BOY CIRCUS BOY 1:00 PM 4:30 PM GREEN ACRES CIRCUS BOY CIRCUS BOY 1:30 PM 5:00 PM I DREAM OF JEANNIE ADV. -

Bewitched Trivia Quiz

BEWITCHED TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> What was the name of the neighbor, who lived next door to the Stephens? a. Abner b. Roger c. Charlie d. Melvin 2> What was Samantha's mother's name? a. Endora b. Hilda c. Martha d. Dorothy 3> What did Darrin Stephens do for a living? a. Lawyer b. Journalist c. Doctor d. Advertizing Executive 4> What is the name of the character played by Paul Lynde? a. Frank Stevens b. Abner Kravitz. c. Uncle Arthur d. Maurice 5> What was the name of Darrin and Samantha's son? a. Larry b. Jonathon c. Maurice d. Adam 6> Where did the Stephens live? a. 705 Hudson Street b. 22 Baker Street c. 1216 Maple Avenue d. 1164 Morning Glory Circle 7> When Samantha got sick, who was called? a. Dr. Bombay b. Dr. Livingstone c. Dr. Spock d. Dr. Jonson 8> What was the name of Samantha's cousin? a. Esmeralda b. Martha c. Clara d. Serena 9> What was Esmeraldas's role on the show? a. Waitress b. Fortune teller c. Secretary d. Housekeeper 10> What was the name of Darrin's daughter? a. Tabitha b. Clara c. Endora d. Dorothy 11> Which famous person appears in the episode "Samantha's French Dessert"? a. Napoleon Bonaparte b. Henri Chopin c. Marie Antoinette d. Louis XIV 12> What type of spell does Serena cast on Darrin's mother? a. She turns her into a teddy bear b. She turns her into a cat c. She sands her to the North Pole. d. -

Activision's Spider-Man 3(TM) Video Game Unleashes the Power of the Black Suit Into North American Retail Stores

Activision's Spider-Man 3(TM) Video Game Unleashes the Power of the Black Suit into North American Retail Stores SANTA MONICA, Calif., May 04, 2007 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- Even the noblest of Marvel's Super Heroes have a dark side - it's time to unleash yours in the Spider-Man 3(TM) video game from Activision, Inc. (Nasdaq: ATVI). Timed to the highly anticipated theatrical release of Sony Pictures Entertainment's Columbia Pictures and Marvel Studios' "Spider-Man 3," based on the famous Marvel characters, the game allows players to experience for the first time Spider-Man's mysterious black-suited persona, as well as heroic red suit while battling villains in a massive New York City playground teeming with activity. "The Spider-Man 3(TM) video game gives fans the chance to relive their favorite scenes from the film, as well as new storylines brought to life by movie talents Tobey Maguire, Topher Grace, Thomas Haden Church, James Franco and J.K. Simmons," said Rob Kostich, vice president, global brand management, Activision, Inc. "Players will swing into action and choose to follow the film plot or new storylines, fight off crime waves, explore vast exterior and underground locations or battle super-villains while harnessing the power of the black suit." Set in a large, dynamic, free-roaming New York City which includes over 20 miles of subterranean environments, Spider-Man 3 (TM) for the PLAYSTATION(R)3 computer entertainment system, Xbox 360(TM) video game and entertainment system from Microsoft and PC, gives players more freedom than ever before to choose their own gameplay experience through multiple movie-based, comic-based and original storylines, fully integrated city missions and performance rewards including improved speed, combat maneuvers and agility. -

The Controversy Surrounding Bewitched and Harry Potter Natalie

Georgia Institute of Technology Which Witch? The Controversy Surrounding Bewitched and Harry Potter Natalie F. Turbiville Department of History, Technology, and Society Georgia Institute of Technology Undergraduate Thesis Friday, April 25, 2008 Advisor: Dr. Douglas Flamming Second Reader: Dr. August Giebelhaus 2 Abstract Beginning in 1999, J.K. Rowling began to receive criticism about her Harry Potter series, which was first published in 1997. Christian Fundamentalists in opposition to the books argued that occult themes present in the series were harmful to the spiritual development of children. Those in opposition cited the negative response to the popular TV series Bewitched during its initial airing in the 1960s as grounds for rejecting Harry Potter . This connection was made because the popular television series and the successful book series both contained witchcraft elements; however, this connection is false. Primary sources show that Bewitched was not challenged based on the issue of witchcraft during its initial airing in the 1960s and 1970s. Despite modern Christian fundamentalists’ claims, the modern negative response to Bewitched is built on contemporary reflection. When Christian fundamentalists seek to prove that their outcry against the witchcraft used in Harry Potter is not unique it is suggested that America had rejected a form of media based on witchcraft when the public spoke out against Bewitched in the 1960s. In fact, the claim that Bewitched received criticism during its initial airing is incorrect. My research shows a direct contemporary correlation between the protest to Harry Potter beginning in 1999 and the rejection of Bewitched by Christian fundamentalists based on the issue of witchcraft. -

06 SM 8/31 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, August 31, 2004 Monday Evening September 6, 2004 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Florida State @ Miami: College Football Local Local Jimmy K KBSH/CBS Still Stand Yes Dear Raymond Two Men CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor Hawaii Last Comic Standing Local Tonight Show Conan FOX North Shore The Complex: Malibu Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E The Riverman The Riverman The Riverman AMC Serpico Manhunter The Real ANIM Growing Up Black Be That's My Baby Miami Animal Police Growing Up Black Be That's My Baby CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King DISC World Biker Build Off World Biker Build Off World Biker Build Off World Biker Build Off World Biker Build Off Norton TV DISN Disney Movie: TBA Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! THS Dr. 90210 Howard Stern SNL ESPN Silver Anniversary Special Major League Baseball ESPN2 NHRA Nationals Sportscenter Outside Baseball T FAM Good Will Hunting Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops HGTV Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce Organize Dsgn Chal Dsgn Dim Dsgn Dme To Go Hunters Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce HIST Engineering Disasters Building a Skyscraper Building A Skyscraper Tactical To Practical Engineering Disasters LIFE In The Name of Love Deadly Encounter How Clea Golden Gr Nanny Nanny MTV The Assistant Road Rule Assistant MTV Special HIp Hop Show Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Srargate SG-1 SPIKE CSI WWE Raw WWE Raw Zone CSI CSI TBS Raymond Raymond The Singer Houseguest TCM Take the High Ground Lord of the Flies Still of the Night TLC What Not To Wear What Not To Wear What Not To Wear What Not To Wear What Not To Wear TNT Law & Order Law & Order Law & Order Law & Order X-Files Your best source for local TV LAND Bewitched Bewitched Bewitched Bewitched Bewitched Bewitched Bewitched Bewitched Cheers Cheers USA Tennis U.S. -

The Paul Lynde Halloween Special” Debuting on October 2

S’MORE ENTERTAINMENT PRESENTS A CLASSIC TELEVISION COLLECTIBLE WITH “THE PAUL LYNDE HALLOWEEN SPECIAL” DEBUTING ON OCTOBER 2 Wherever Paul Lynde appeared, the audience knew they would witness comedic brilliance and rapid-fire wit. The actor/comedian, perhaps best known for his classic residency as the center square of the famous game show, “Hollywood Squares,” was an accomplished Broadway actor, as well as a regular on some of the most revered television programs of the late ‘60s. But it is “THE PAUL LYNDE HALLOWEEN SPECIAL” that best captures the brilliant comedian in a holiday special that featured a literal “who’s who” of the entertainment business including the first prime time television appearances of rock icon KISS and film star Margaret Hamilton, the original wicked witch from The Wizard Of Oz, appearing in full witch regalia. This unique special aired only once, on October 29, 1976. “THE PAUL LYNDE HALLOWEEN SPECIAL” is a television “classic” in the truest sense of the word, making this single disc DVD uniquely collectible. The priceless humor is supplied by such talented guests as Tim Conway, Billy Barty, Margaret Hamilton (The Wicked Witch of the West), Billy Hayes (Witchie Poo from “H.R. Pufnstuf”) and Florence Henderson with cameo appearances by Betty White, Donnie & Maria Osmond and Roz Kelly (Pinky Tuscadero from “Happy Days”). The show has always been the ‘holy grail for KISS fans as the super group performs 3 songs: “Beth”, “King of the Nighttime World” and “Detroit Rock City” A native of Mt. Vernon, Ohio, Paul Lynde aspired to success as an actor from an early age, despite the objections of his conservative father, a local police officer and the sheriff of the Mount Vernon jail. -

The Paul Lynde Story Ebook, Epub

CENTER SQUARE : THE PAUL LYNDE STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joe Fiorenski | 240 pages | 01 Aug 2005 | Alyson Publications Inc | 9781555837938 | English | Boston, United States Center Square : The Paul Lynde Story PDF Book Retrieved July 29, Too overwhelming for the star of a TV show or film. He felt those failures deeply and turned more and more to alcohol, which began to impact negatively on his career. Most importantly, as far as his fans are concerned, he played the jokester warlock Arthur on Bewitched , where all of his comic skills were allowed to shine. And he was sensitive about being gay and his social life. It did have a couple of funny parts and did have a part here and there that gave him the full view of what he was like and his life. Indeed, he came out of it full of insecurities, some because of his weight, others because he was gay at a time when homosexuality was not an openly-accepted lifestyle. Also, Lynde was not movie star lead material. I don't read about Lynde's checkered career, read the endless cyclical patterns with overeating, drunken meanness, or encounters with dangerous hustlers and say "well, he's earned it. He was 55 years old. Aug 15, James rated it it was ok. He was trying to stop drinking completely, he was cutting down his smoking, and trying to focus on a more holistic lifestyle. The bottom line is that all of those on the Bewitched set, in front of and behind the scenes, knew of his sexuality. -

178 Samantha Stevens of Bewitched on Her Perch

178 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2012 Samantha Stevens of Bewitched on Her Perch This statue was installed in 2005 amid great controversy. 179 Bewitched and Bewildered: Salem Witches, Empty Factories, and Tourist Dollars ROBERT E. WEIR Abstract: In 2005, witchcraft hysteria once again roiled the city of Salem, Massachusetts. This time, however, city residents divided over a new monument—a statue honoring Samantha Stephens, a fictional witch from the television sitcom Bewitched. In the minds of many, the Stephens statue was tacky and an insult to the history, memory, and heritage of the tragic days of 1692, when a more deadly hysteria led to the executions of twenty townspeople. To the statue’s defenders, the Samantha Stephens representation was merely a bit of whimsy designed to supplement marketing plans to cement Salem’s reputation as a tourist destination. This article sides largely with the second perspective, but with a twist. It argues that Samantha Stephens is worthy of memorializing because the 1970 filming ofBewitched episodes in Salem is largely responsible for the city’s tourist trade. The article traces changing perspectives on witchcraft since the seventeenth century and, more importantly, places those changes in economic context to show the mutability of history, memory, and heritage across time. Ultimately, Samantha Stephens helped rescue Salem from a devastating twentieth-century demon: deindustrialization. Dr. Robert E. Weir is the author of six books and numerous articles dealing with social, labor, and cultural history.1 * * * * * Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 40 (1/2), Summer 2012 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 180 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2012 On June 15, 2005, the city of Salem, Massachusetts unveiled its newest monument. -

Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. in Re

Electronically Filed Docket: 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD (2010-2013) Filing Date: 12/29/2017 03:41:40 PM EST Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF THE MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS 2010-2013 SATELLITE ROYALTY YEARS VOLUME I OF II WRITTEN TESTIMONY AND EXHIBITS Gregory O. Olaniran D.C. Bar No. 455784 Lucy Holmes Plovnick D.C. Bar No. 488752 Alesha M. Dominique D.C. Bar No. 990311 Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP 1818 N Street NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 355-7917 (Telephone) (202) 355-7887 (Facsimile) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for MPAA-Represented Program Suppliers December 29, 2017 Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS FOR 2010-2013 SATELLITE ROYALTY YEARS The Motion Picture Association of America, Inc. (“MPAA”), its member companies and other producers and/or distributors of syndicated series, movies, specials, and non-team sports broadcast by television stations who have agreed to representation by MPAA (“MPAA-represented Program Suppliers”),1 in accordance with the procedural schedule set forth in Appendix A to the December 22, 2017 Order Consolidating Proceedings And Reinstating Case Schedule issued by the Copyright Royalty Judges (“Judges”), hereby submit its Written Direct Statement Regarding Distribution Methodologies (“WDS-D”) for the 2010-2013 satellite royalty years2 in the consolidated 1 Lists of MPAA-represented Program Suppliers for each of the satellite royalty years at issue in this consolidated proceeding are included as Appendix A to the Written Direct Testimony of Jane Saunders. -

Color on the Networks

Two_thirds Tint· NBC is now show ing 28 out of 29 shows in color, CBS Color on the networks: J7 out of 34 and ABC 16 out of 35, for a total of 61 out of 98, A vicwer looking for periods in color on all networks now could find nine such half-hours OUt of 49 in the nighttime well on way to 100% schedule. The nine occur on Sunday (1:30-8, 8-8:30 and 8:30-9), Wednes_ day (8:30-9 and 9-9:30) and Thursday NBC, which started it all, still has a big lead, (8-8:30, 8:30-9, 10-10:30 and 10:30 11), but ABC and CBS are investing millions to catch up Color's incidence is history at NBC. That network telccast a total of 68 hours in color during the entire year The television networks arc following ment supply for Ihat network does not of 1954, thc first year after present up the color explosion of 1965 with include cameras. Aside from the CBS color standards were approvcd by plans 10 accommodate a second color qualification, the shortages gcnerally the FCC, At midpoint in the 1965-66 burst in the faU of 1966. cover cameras, film chains, tape ma season, NBC is colorcasting at a sea Accommodation means more funds, chines and monitors. All the networks sonal rate of more than 3,000 hours, is facilities and programing -allocated to are ordering color mobile units to add still adding some color now and plans color. Color investments of the nct to studio gear.