A Case Study of Varthur Lake, Bangalore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

502B Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

502B bus time schedule & line map 502B Maduranagar - Krishnarajendra Market View In Website Mode The 502B bus line (Maduranagar - Krishnarajendra Market) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Krishnarajendra Market: 7:45 AM - 1:50 PM (2) Maduranagar: 9:10 AM - 3:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 502B bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 502B bus arriving. Direction: Krishnarajendra Market 502B bus Time Schedule 29 stops Krishnarajendra Market Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:45 AM - 1:50 PM Monday 7:45 AM - 1:50 PM Maduranagar Tuesday 7:45 AM - 1:50 PM Maduranagar Hostel Wednesday 7:45 AM - 1:50 PM Janatha Mane Thursday 7:45 AM - 1:50 PM Sarahunise Gate Friday 7:45 AM - 1:50 PM Varthoor College Saturday 7:45 AM - 1:50 PM Varthur Main Road, Bangalore Varthuru Kodi Varthur Road, Bangalore 502B bus Info Ramagondanahalli Varthuru Direction: Krishnarajendra Market Varthur Road, Bangalore Stops: 29 Trip Duration: 48 min Siddapura Line Summary: Maduranagar, Maduranagar Hostel, Janatha Mane, Sarahunise Gate, Varthoor College, Thubarahalli Varthuru Kodi, Ramagondanahalli Varthuru, Siddapura, Thubarahalli, Kundalahalli Gate, Spice Kundalahalli Gate Garden, Maratahalli Bridge, Maratahalli, Borewell, H.A.L Kalyana Mantapa, Helicopter Division, H.A.L.Main Gate, Rajeshwari Talkies, Murgeshpalya, Spice Garden Manipal Hospital, Kodihalli Domlur, Domlur T.T.M.C., Foot bridge, Bangalore Commando Hospital, Military Accounts O∆ce, Life Style, Richmond Circle, Corporation, Town Hall, Maratahalli Bridge Krishnarajendra Market 97/2, 1st Floor Marathahalli Underpass,97/2 Maratahalli 336 Ground Floor Varthur Road, Marathahalli Borewell H.A.L Kalyana Mantapa Helicopter Division H.A.L.Main Gate Rajeshwari Talkies Murgeshpalya Manipal Hospital Kodihalli Domlur Domlur T.T.M.C. -

331 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

331 bus time schedule & line map 331 Kadugodi - Shivajinagar Bus Station View In Website Mode The 331 bus line (Kadugodi - Shivajinagar Bus Station) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Kadugodi: 5:30 PM (2) Shivajinagar Bus Station: 9:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 331 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 331 bus arriving. Direction: Kadugodi 331 bus Time Schedule 28 stops Kadugodi Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:30 PM Monday 5:30 PM Shivajinagara Bus Station Tuesday 5:30 PM Manipal Centre Wednesday 5:30 PM Trinity Circle Thursday 5:30 PM Military Accounts O∆ce Friday 5:30 PM Commando Hospital Saturday 5:30 PM Domlur Madiwala Machideva Road, Bangalore Kodihalli 331 bus Info Direction: Kadugodi Manipal Hospital Stops: 28 Trip Duration: 58 min Murugeshpalya Line Summary: Shivajinagara Bus Station, Manipal Centre, Trinity Circle, Military Accounts O∆ce, Commando Hospital, Domlur, Kodihalli, Manipal Rajeshwari Talkies Hospital, Murugeshpalya, Rajeshwari Talkies, H.A.L.Main Gate, H.A.L Kalyana Mantapa, Borewell, H.A.L.Main Gate Marathahalli, Marathahalli Bridge, Spice Garden, Kundalahalli Gate, Thubarahalli, Siddapura, H.A.L Kalyana Mantapa Ramagondanahalli, Varthuru Kodi, Brook Bond, Varthur Road, Bangalore White Field, Sai Baba General Hospital, Munish Hospital, Hope Farm, Prajwal School, Kadugodi Bus Borewell Station Marathahalli Varthur Road, Bangalore Marathahalli Bridge Marathahalli Skywalk, Bangalore Spice Garden Foot bridge, Bangalore Kundalahalli Gate Thubarahalli -

List of Affiliated Colleges College Slno College Address Town District Phone 01 Phone 02 Email Code 1 6001 Govt

List of affiliated Colleges College Slno College Address Town District Phone 01 Phone 02 email Code 1 6001 Govt. First Grade College for Boys Kolar - 563 101 Kolar Kolar 9448703610 08152-222014 2 6002 Govt. First Grade College for Women Kolar - 563 101 Kolar Kolar 9448310292 9448551944 3 6003 Govt. First Grade College Bangarpet - 563 114 Bangarpet Kolar 9739601069 4 6004 Govt. First Grade College Bangaru Tirupathi Bangaru Tirupathi Kolar 8277490804 08153-277088 5 6005 Govt. First Grade College Behind BEO Office, Robertsonpet, 3rd Cross, KGF - 563 122 K.G.F Kolar 7204783372 6 6006 Govt. First Grade College Malur - 563 130 Malur Kolar 9886152726 9448562961 7 6007 Govt. First Grade College Mulabagalu - 563 131 Mulbagal Kolar 9886668896 8 6008 Govt. First Grade College Mulabagalu - 563 131 Mulbagal Kolar 9886668896 [email protected] 9 6009 Govt. First Grade College Srinivasapura - 563 135 Srinivasapura Kolar 9663701201 08157-246804 10 6010 Govt. First Grade College Vemgal - 563 101 Vemagal Kolar 9886632427 08152 246499 Smt. Danamma Channabasavaiah College of Arts, Commerce, 11 6101 Opp. to SBI Bank, Kolar Main Road, Bangarpet Bangarpet Kolar 9141814905 9060777990 [email protected] Science & Management Studies K.G.F Main road, near food godown, S.G. Kote post, Bangarpet - 12 6102 Alpha Degree College Bangarpet Kolar 9900023325 563 162 13 6103 K.G.F Frist Grade College Oorgam, K.G.F. - 563 120 K.G.F Kolar 9449730978 9449730798 14 6104 Sri Baghawan Mahaveer Jain Degree College Geetha Road, Robertsonpet, KGF - 563 122 K.G.F Kolar -

Aro Details.Xlsx

Bommanahalli Zone Office Ph.No Zonal Officers Name of the Officer Mobile No. Email Id Office Address (Prefix -080) 25732447, Joint Commissioner Rama Krishna 9480683433 [email protected] 25735642 Begur Road, Bommanahalli, Banglaore – 560068 Deputy Commissioner N.Shashikala 9480684171 25735608 [email protected] Name of the RO Revenue R.O’s Mobile No. Office Ph.No ARO Sub-division Ward No. & Name Assistant Revenue Mobile No. Email Id Office Address Division Officer & Office Ph.No (Prefix -080) Officer 175 - Bommanahalli Bommanahalli 188 - Bilekahalli Nataraj 9480685528 25735000, [email protected] Begur Road, Bommanahalli, Bengaluru 189 - Hongasandra 186 - Jaraganahalli 9480683167 Bannerghatta Road, MICO Layout, Balachandra Arakere 187 - Puttenahalli S V Manjunath 9731103437 26467619 [email protected] 25735390 Bengaluru. 193 - Arakere Bommanhalli 174 - HSR Layout 7892757079 Behind BDA Complex HSR 6TH Sector, HSR Layout Lakshmi 25725964 [email protected] 190 - Mangammanapalya 9th Main, 14TH A Cross, HSR Layout 191 – Singasandra 9480683006 Old Gram Panchayath Office, Begur, Begur Ananthramaiah 25745300 [email protected] 192 - Begur Banglore. Y. Muniyappa 9480684143 Anjanapura 194 - Gottigere Old Gram Panchayath Office, Begur, Anjanapura Ramesh 9731383407 22453000 [email protected] 196 - Anjanapura Banglore. 195 - Konanakunte Konanakunte Cross, Kanakapura Road, Yelachenahalli Rangaswamy 9480684564 26321177 [email protected] 185 - Yelachenahalli Bengaluru, 9480684034 Venkatesh 25735394 Uttarahalli 184 - Uttarahalli Near Subramanyapura Police Station, Uttarahalli Devaraj 9448905713 [email protected] 197 -Vasanthapura Bengaluru Dasarahalli Zone Office Ph.No Zonal Officers Name of the Officer Mobile No. Email Id Office Address (Prefix -080) BBMP Dasarahalli Joint Joint Commissioner Sri. Narashimamurthy [email protected] 9036828015 22975901 Commissioner MEI layout, Hesargatta Main road, Deputy Commissioner Sri. -

500KK Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

500KK bus time schedule & line map 500KK Kadugodi Bus Station - Koramangala TTMC View In Website Mode The 500KK bus line Kadugodi Bus Station - Koramangala TTMC has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Koramangala Ttmc: 9:05 AM - 7:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 500KK bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 500KK bus arriving. Direction: Koramangala Ttmc 500KK bus Time Schedule 36 stops Koramangala Ttmc Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:05 AM - 7:50 PM Monday 9:05 AM - 7:50 PM Kadugodi Bus Station Tuesday 9:05 AM - 7:50 PM Hope Farm Wednesday 9:05 AM - 7:50 PM Bpl Thursday 9:05 AM - 7:50 PM Gr Tech Park Itpl Friday 9:05 AM - 7:50 PM I.T.P.L.Whiteƒeld Saturday 9:05 AM - 7:50 PM Pattandur Agrahara Gate Big Bazar I.T.P.L. 500KK bus Info Sathya Sai Hospital Direction: Koramangala Ttmc Stops: 36 Trip Duration: 58 min Whiteƒeld T.T.M.C. (Vydehi Hospital) Line Summary: Kadugodi Bus Station, Hope Farm, 2nd Road, Bangalore Bpl, Gr Tech Park Itpl, I.T.P.L.Whiteƒeld, Pattandur Agrahara Gate, Big Bazar I.T.P.L., Sathya Sai K.T.P.O. (I.T.P.L.Road) Hospital, Whiteƒeld T.T.M.C. (Vydehi Hospital), 2nd Road, Bangalore K.T.P.O. (I.T.P.L.Road), I.Gate (I.T.P.L.Road), S.A.P.Labs, Graphite India, Kundalahalli Colony, I.Gate (I.T.P.L.Road) C.M.R.I.T. -

Karnataka 1. Dr. K.G.Balakrishnan E 135, Sobha Hibiscus, Sarjapur

Karnataka 1. Dr. K.G.Balakrishnan 2. Dr. Vijayalakshmi I. Balekundra E 135, Sobha Hibiscus, Aditi, 44A, V Main Road Sarjapur Outer Ring Road, Vijayanagar II Stage Bellandur, Bangalore-560103 Hampinagar Bangalore-560040 3. Dr.Asit Kumar Chakraborty 4. Dr. A. Chandramuki "Bikalpa", 557, 526, 11th Main, 4th Block, 8th Main, Jayanagar, Koramangala, 5th Block, Bangalore-560034. Bangalore-560041. 5. Dr. S Prabha Chandra 6. Dr. George Cherian Professor, House No. 828, Department of Psychiatry, 13th Main Road, National Institute of Mental Health 3 Block, Koramangala, and Neuro Sciences, Bangalore – 560034 Bangalore-560029 7. Dr. Bikramjit Basu 8. Dr. B.N. Gangadhar Material Research Center Professor Indian Institute of Sciences Deptt. of Psychiatry Bangalore-560012 National Instt. of Mental Health & Karnataka Neurosciences, P.O. Box 2900, Hosur Road, Bangalore-560028 9. Dr.K.S. Gopinath 10. Dr. Gomathy Gopinath Director, Flat No. 001 Consultant Surgical Oncologist, Kanchanjunga Apptts. Bangalore Institute of Oncology, 122/2, Nagavarapalya 44-45/2, 2nd Cross, C.V. Raman Nagar R.M.R.R. Exten., Bangalore – 560093 Bangalore-560027. 11. Dr.P.G.Gopinathan Nair 12. Dr. Chhitar Mal Gupta, FAMS Flat No. 001 Appt. No. D-508, Raheja Residency, Ground Floor 3rd Block, Koramangala, Kanchanjunga Apptts. Bangaluru-560034 122/2, Nagavarapalya C.V. Raman Nagar Bangalore – 560093 13. Dr. Gopalkrishna Gururaj 14. Dr. C.V. Harinarayan No. 74, Unnathi, Shree, No 260, 4th Main Road Mountain Road, (Near Ayyappa Temple) 1st Block East, Jayanagar, Vijaya Bank Colony Bangalore-560011 (Behind IIM-B), Bangalore-560076 15. Dr.B.M.Hegde 16. Dr. Usha Kini Manju Nath, 524, 20th Main Pai Hills, Bijai 4th T Block, Jayanagar Mangalore - 575004 Bangalore-560041 17. -

102 Status of Varthur Lake

Technical Report : 102 STATUS OF VARTHUR LAKE: OPPORTUNITIES FOR RESTORATION AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT Ramachandra T V, Ahalya N and Mandy Payne Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES), Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore - 560012, INDIA http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/energy/ Email: [email protected], [email protected] SUMMARY Lake ecosystems vital functions such as recycling of nutrients, purification of water, recharge of groundwater, augmenting and maintenance of stream flow and habitat provision for a wide variety of flora and fauna along with their recreation values necessitates their sustainable management through appropriate conservation mechanisms. Failure to restore these ecosystems will result in extinction of species or ecosystem types and cause permanent ecological damage. In Bangalore, lakes have played a prominent role serving the needs of agriculture and drinking water. But the burgeoning population accompanied by unplanned development has led to the drastic reduction in their numbers (from 262 in 1976 to 81 at present). The existing water bodies are contaminated by residential, agricultural, commercial and industrial wastes/effluents. Varthur lake is situated in the south taluk of Bangalore district. It has a large surface area and is the main irrigation source to the nearby agricultural fields and supports a wide variety of flora and fauna. The main aim of undertaking the present study was to evaluate the ecological status of the Varthur lake, the results of which would help in restoration efforts. The study consisted of three parts (i) Morphometric survey – to provide the information on the depth, surface area, width, etc of the lake; (ii) Water quality survey – to elucidate the quality of lake water and the nearby groundwater; (iii) Socio-economic survey – to assess the dependency of the nearby residents on the lake ecosystem. -

Bus Route: No 02 Nagarbavi Via East Point Academy

BUS ROUTE: NO 02 NAGARBAVI VIA EAST POINT ACADEMY STOPS TIMINGS NAGARABAVI 6:30 MOODLU PALYA 6:40 VIJAYANAGAR 6:50 VIJAYANAGARA TOO GATE 7:00 NAVARANGA THEATER 7:10 MALLESHWARAM 7:15 BANGALORE CANTONMENT 7:20 RAILWAY STATION ULSOOR LAKE 7:25 ITC 7:30 BHARATHNAGAR 7:32 SEVANAGAR 7:34 AYYAPPA TEMPLE 7:36 UTTHAM SAGAR 7:38 EAST POINT ACADEMY 7:40 ROYAL CONCORDE 7:45 BABUSAPALYA 7:48 JAYANTHINAGAR 7:55 KALKERE 7:57 RAMPURA 8:00 BIDARAHALLI 8:05 EPGI 8:10 BUS ROUTE – NO 09 J.P.NAGAR ROUTE STOPS TIMINGS VEGA CITY 6:00 SARAKKI SIGNAL 6:20 EAST END CIRCLE 6:25 JAYA DEVA HOSPITAL 6:30 UDUPI GARDEN 6:35 BTM LAYOUT 6:40 SILK BOARD 6:45 MADIVALA 6:50 AYYAPPA TEMPLE 6:52 POLICE QUARTERS 6:55 JAKKASANDRA 6:58 HSR LAYOUT 7:00 AGARA 7:02 SARJAPUR BRIDGE 7:05 BELLANDUR 7:07 MARATHALLI 7:10 KUNDALAHALLI GATE 7:15 THOOBARAHALLI 7:17 SIDDAPURA 7:20 VARTHUR KODI 7:25 WHITEFIELD 7:30 AMBEDKAR NAGARA 7:32 HOPE FARM SIGNAL 7:37 KADUGODI BRIDGE 7:40 BELTHUR 7:42 SEEGEHALLI 7:46 KANNAMANGALA 7:50 KATAMNALLUR CROSS 7:55 BUDIGERE CROSS 7:58 AVALAHALLI 8:00 EPGI 8:05 BUS ROUTE: NO 03 SRINIVASPUR VIA KOLAR ROUTE STOPS TIMINGS SRINIVASAPURA 6:15 DALASANOOR TBA ROJARNALLI TBA MUDAVADI TBA ARANAGANAHALLI 6:35 BAIRE GOWDA ENGINEERING TBA COLLEGE MURANDAHALLI 6:40 KEEL KOTE TEMPLE 6:50 NEW BUS STAND 6:55 TOWER – MARKET 7:00 APMC MARKET 7:05 NARASAPURA 7:20 CHIKKANAHALLI GATE 7:30 MUGBALA 7:35 HOSKOTE 7:45 AVALAHALLI 7:55 EPGI 8:00 BUS ROUTE – NO 04 MULBAGAL ROUTE STOPS TIMINGS MULBAGAL BUS STAND 6:00 AMBEDKAR CIRCLE 6:05 KANTHARAJ CIRCLE 6:10 MOTHER DAIRY 6:30 TAMAKA 6:35 -

Designated Bank Branches List for Payment

AXIS BANK BRANCHES IN BANGALORE CITY Branch BranchAddress Jayanagar JayanagarBranch,Sona Towers, No 8,32 E Cross,4th TBlock,Jayanagar,Bangalore-560041. KeersPlaza- Basveshwar Nagar 2000,472,80FTMainRoadBasveshwarnagar,Bangalor e560079 NO 688 IIIA Cross Opp.Seshadripuram CollegeNew Yelahanka TownYelahankaBangalore560064 No566&567,30thmainroad,Katriguppe,Banashankari Banashankari ,3rdstage(nexttomegamart)Bangalore-560085 Indiranagar #774,100FTRoadIndiraNagarBangalore560038 NO.119,80FeetRoad,7thBlock Koramangala IndustrialLayout,KoramangalaBangalore560095 233,2nd Malleswaram Main,SampigeRoad,MalleswaramBangalore 560003 MINUTH CRESENT, NO. 56, COLES ROAD, Cox Town FRASERTOWN,BANGALORE-560005 SiteNo.43,Varthur Main Marathahalli RoadMarathahalliIBangalore560037 Ground Floor, No.6/A,JP NagarIII J.P.Nagar Phase,BannergattaMainRoadBangalore560076 G.G.Arcade,ServiceRoad,NO.2940/E- Vijayanagar 5WestOfChordRoad,OppMarutiMandir,VijayanagarBang alore560040 "CITIUS",FirstTechnology PlaceNo.3, White field EPIP,WhitefieldBangalore560066 No. 5/111,I Main,IBlock, Dr. RajkumarRoad, Rajajinagar Rajajinagar,Bangalore-560010. 100Ft. Road,149,PeenyaIndustrial Peenya Estate,PeenyaIstStage,Bangalore-560057 Sahakaranagar No19,60ftroad,Sahakaranagar,Bangalore560092 HGPlaza,No.223/B,Konnapana Electronic City Agrahara,ElectronicCityBangalore560100 PlotNo.41,SeshadriRoad,Anand Majestic RaoCircleBangalore560009 No 30,4thcross,CMR Road,Kalyannagar,HRBR KalyanNagar 2ndblock,Bangalore-560043 Sanjay Nagar 23/4DRajagopal Road,SanjayNagarBangalore-560094 SiteNo.2621,27thMain,Sector1,OppositeCPWDQu -

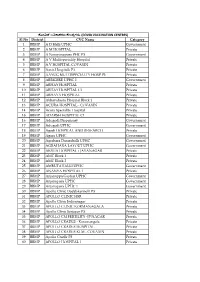

Sl No District CVC Name Category 1 BBMP a D Halli UPHC Government

ಕ ೋ풿蓍 ಲಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋᲂ飍ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Name Category 1 BBMP A D Halli UPHC Government 2 BBMP A M HOSPITAL Private 3 BBMP A Narayanapura PHC P3 Government 4 BBMP A V Multispeciality Hospital Private 5 BBMP A.V.HOSPITAL COVAXIN Private 6 BBMP Aaxis Hospitals P3 Private 7 BBMP AAYUG MULTISPECIALTY HOSP P3 Private 8 BBMP ABBIGERE UPHC 1 Government 9 BBMP ABHAY HOSPITAL Private 10 BBMP ABHAY HOSPITAL C1 Private 11 BBMP ABHAYA HOSPITAL Private 12 BBMP Abhayahasta Hospital Block 1 Private 13 BBMP ACURA HOSPITAL - COVAXIN Private 14 BBMP Acura Speciality Hospital Private 15 BBMP ADARSH HOSPITAL C1 Private 16 BBMP Adugodi Dispensary Government 17 BBMP Adugodi UPHC Government 18 BBMP Agadi HOSPITAL AND RESEARCH Private 19 BBMP Agara UPHC Government 20 BBMP Agrahara Dasarahalli UPHC Government 21 BBMP AGRAHARA LAYOUT UPHC Government 22 BBMP AKSHA HOSPITAL - JAYANAGAR Private 23 BBMP AMC Block 1 Private 24 BBMP AMC Block 2 Private 25 BBMP AMRUTAHALLI UPHC Government 26 BBMP ANANYA HOSPITAL 1 Private 27 BBMP Anjanappa Garden UPHC Government 28 BBMP Anjanapura UPHC Government 29 BBMP Anjanapura UPHC 1 Government 30 BBMP Apollo Clinic Doddakannelli P3 Private 31 BBMP APOLLO CLINIC HSR Private 32 BBMP Apollo Clinic Indiranagar Private 33 BBMP APOLLO CLINIC KORMANAGALA Private 34 BBMP Apollo Clinic Sarjapur P3 Private 35 BBMP APOLLO CM FERTILITY -JP NAGAR Private 36 BBMP APOLLO CRADLE - Koramangala Private 37 BBMP APOLLO CRADLE HOSPITAL Private 38 BBMP APOLLO CRADLE KLM - COVAXIN Private 39 BBMP Apollo Cradle P3 Private 40 BBMP APOLLO HOSPITAL 1 Private 41 BBMP APOLLO HOSPITAL BG Private 42 BBMP APOLLO HOSPITAL SHESHADRIPURAM Private 43 BBMP APOLLO HOSPITAL-C1 Private 44 BBMP Apollo Hospital-JAYANAGAR Private 45 BBMP APOLLO MEDICAL CENTER P3 Private 46 BBMP APOORVA Block 1 Private 47 BBMP APOORVA Hospital C1 Private 48 BBMP APTS UPHC Government 49 BBMP Arakere Uphc Government 50 BBMP Arka Hospital Private 51 BBMP ARTYEM HOSPITAL Private 52 BBMP ARTYEM HOSPITAL C1 Private 53 BBMP ARYAN MULTISPECIALITY HOS. -

Sl.No. Customer Name Address 1 a N SRINIVASA a M NARAYANAPPA ANDKEMPAMMA , SB-1291

Sl.No. Customer Name Address 1 A N SRINIVASA A M NARAYANAPPA ANDKEMPAMMA , SB-1291 , . BANGALORE 2 ABDUL KHUDDUS JABARTRAVELS , 19/3 A.V.ROAD KALASIPALYAM , . BANGALORE 3 ABDUL LATHIF K SB-1370 , . , . BANGALORE 4 ABDUL RAHAMAN T HAJIRA SULTA 17 1STFLOOR 3RDCROSS , T.C.MROYANROAD , . BANGALORE 5 ABDUL RAHSEED TN.109 BATTERYDEPT. , 1/1 VITTALMALLYAROAD UBLTD , . BANGALORE 6 ABDUL RAWOOF SB-1331 , . , . BANGALORE 7 ABDUL SALAM SARI SONS RICEBRAN CATTLEFEED&GENERALMERCHANTS , NO16 TCMROYANROAD , . BANGALORE 8 ABDUL SHUKOOR SENIORINSPECTOROFCO-OPSOCIETIES , O/OJRCS BANGALOREDIVISION , . BANGALORE 9 ABDUL WAJID SB-2797 , . , . BANGALORE 10 ADARSH ROAD CARRIERS BANGALORE , . , . BANGALORE 11 ADIKESHAVAN A.167 BINNYPET , . , . BANGALORE 12 ADINARAYANA B N 3/2 ROOMNO.1 ISTMNRD ICROSS , CHAMARAJPET , . BANGALORE 13 ADINARAYANAIAH C 560/11 AVENUEROAD , . , . BANGALORE 14 ADISESHA MURTHY M R 33/3 4THMAINROAD , CHAMARAJPET , . BANGALORE 15 AGARA CO OP SOCIETY LIMITED AGARA , BANGALORESOUTHTALUK , . BANGALORE 16 AGNES NAZAREETH NO.15 4THMAIN GAYATHRINAGAR , 7THCROSS , . BANGALORE 17 AKHILAKHATOON FEMALEHEALTHASSISTANT BELEDEVALAYA , SUB-CENTRE KUNIGAL(4367) , . BANGALORE 18 AKILA BHARTHKURAHINA SHETTY YU 19 NEWHIGHSCHOOLROAD , V.V.PURAM , . BANGALORE 19 AKKAYAMMA SB-992 , . , . BANGALORE 20 ALL INDIA SHEDULED CASTE DEVEL SOCIETY , . , . BANGALORE 21 ALL INDIA VEERASAIVA MAHASABHA KARNATAKASTATEUNIT , . , . BANGALORE 22 ALLAH BAKASH S PSI CENTRALPOLICESTATION , CHAMARAJPET , . BANGALORE 23 AMAREGOWDA BYYAPURAKALAGOWDAJIPOST , LINGASUGURTQ. , . BANGALORE 24 AMARNATH A JIGANI ANEKALTQ. , . , . BANGALORE 25 AMARNATH L 7 12MAINROAD , RAGHAVENDRABLOCK SRINAGAR , . BANGALORE 26 ANAND B M JAYANAGAR , BANGALORE , . BANGALORE 27 ANAND B S STAFF NO119/5MPVHOUSE16THMAIN , 16MAINROADVIJAYANAGARBLORE , . BANGALORE 28 ANAND ENTERPRISES 639 22MAINROAD , 4THBLOCKJAYANAGAR , . BANGALORE 29 ANANDA H K 42/6 ICROSS VITTALNAGAR , CHAMRAJPET , . BANGALORE 30 ANANDA KUMAR M 3/1A , 3RDCROSS 6THMAIN NR.COLONY , . BANGALORE 31 ANANDA RAO K 309/5 IFLOOR , 40THCROSS JAYANAGAR 8THBLOCK , . -

Dell International Services India

Certificate of Registration ROAD TRAFFIC SAFETY MANAGEMENT SYSTEM This is to certify that: Dell International Services India Pvt Ltd & Dell India Pvt Ltd(DELL-4) Divyasree Greens, Survey No.12/1, 12/2A, Challaghatta Village, Varthur Hobli Koramangala, Domlur Post Bangalore 560 071 Karnataka India Holds Certificate No: RTS 659104 and operates a Road Traffic Safety Management System which complies with the requirements of BS ISO 39001:2012 for the following scope: To Provide Safe and Secure Road Transport services to the users. For and on behalf of BSI: Managing Director, BSI India, Venkataram Arabolu Original Registration Date: 2017-09-02 Effective Date: 2017-09-02 Latest Revision Date: 2017-09-02 Expiry Date: 2020-09-01 Page: 1 of 2 This certificate was issued electronically and remains the property of BSI and is bound by the conditions of contract. An electronic certificate can be authenticated online. Printed copies can be validated at www.bsi-global.com/ClientDirectory or telephone +91 11 2692 9000. Further clarifications regarding the scope of this certificate and the applicability of ISO 39001:2012 requirements may be obtained by consulting the organization. This certificate is valid only if provided original copies are in complete set. BSI, The MIRA Corporate Suites (A-2), Plot 1 and 2, Ishwar Nagar, Mathura Road, New Delhi 110 065. A Member of the BSI Group of Companies. Certificate No: RTS 659104 Location Registered Activities Dell International Services India To Provide Safe and Secure Road Transport services to the Pvt Ltd & Dell India Pvt Ltd(DELL-4) users. Divyasree Greens, Survey No.12/1, 12/2A, Challaghatta Village, Varthur Hobli Koramangala, Domlur Post Bangalore 560 071 Karnataka India Dell International Services To Provide Safe and Secure Road Transport services to the India Pvt.