An Interview with György Ligeti in Hamburg Stephen Satory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

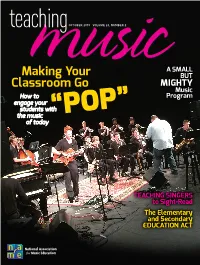

Making Your Classroom Go

teaching OCTOBER 2015 VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2 A SMALL Makingmusicmusic Your BUT Classroom Go MIGHTY Music How to Program engage your students with the music “POP” of today TEACHING SINGERS to Sight-Read The Elementary and Secondary EDUCATION ACT QuaverFindOutAd_NAfME_Aug15.pdf 1 7/30/15 12:26 PM Find out what these districts already know... Quaver is revolutionizing music education! TM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Packed with nearly 1,000 Songs! Try 36 Lessons from our K-8 Curriculum! Just go to QuaverMusic.com/Preview and begin your FREE 30-day trial today! ©2015 QuaverMusic.com, LLC October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 contentsMUSIC EDUCATION ● ORCHESTRATING SUCCESS Music students learn cooperation, discipline, and teamwork. 28 Teachers and students alike can rock out and learn with pop music! FEATURES 24 TEACHING SINGERS 28 POP AND ROCK GOES 32 EL SISTEMA TODAY 38 SMALL SCHOOL, TO READ THE PROGRAM! José Antonio Abreu’s BIG EFFORT, Instructing students in Pop music connects creation has taken GREAT SUCCESS the art and techniques instantly with many root in the U.S. and Alexandria Hanessian’s of sight-singing can reap students. How can continues to grow small but mighty middle many rewards in your music educators use through programs such school program thrives choral rehearsals and it in their classrooms as the Corona Youth in Spencertown, beyond. to increase student Music Project and New York. engagement? Juneau Alaska Music Matters. Photo by Little Kids Rock. Photo by nafme.org 1 October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 Student composers contents (far left and right) work with teachers Conductor Marin Alsop 56 at Williamsville East works with students in High School. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:07 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2011 This essay offers broad reflection on some of the challenges faced by African composers of art music. The specific point of departure is the publication of a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar new anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Ghanaian pianist and scholar William Chapman Nyaho and published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. The anthology exemplifies a diverse range of See table of contents creative achievement in a genre that is less often associated with Africa than urban ‘popular’ music or ‘traditional’ music of pre-colonial origins. Noting the virtues of musical knowledge gained through individual composition rather than ethnography, the article first comments on the significance of the Publisher(s) encounters of Steve Reich and György Ligeti with various African repertories. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Then, turning directly to selected pieces from the anthology, attention is given to the multiple heritage of the African composer and how this affects his or her choices of pitch, rhythm and phrase structure. Excerpts from works by Nketia, ISSN Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi and Osman serve as illustration. 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Agawu, K. (2011). The Challenge of African Art Music. Circuit, 21(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart – Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Mozart entered this concerto in his catalog on February 10, 1785, and performed the solo in the premiere the next day in Vienna. The orchestra consists of one flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. At these concerts, Shai Wosner plays Beethoven’s cadenza in the first movement and his own cadenza in the finale. Performance time is approximately thirty-four minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20 were given at Orchestra Hall on January 14 and 15, 1916, with Ossip Gabrilowitsch as soloist and Frederick Stock conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on March 15, 16, and 17, 2007, with Mitsuko Uchida conducting from the keyboard. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 6, 1961, with John Browning as soloist and Josef Krips conducting, and most recently on July 8, 2007, with Jonathan Biss as soloist and James Conlon conducting. This is the Mozart piano concerto that Beethoven admired above all others. It’s the only one he played in public (and the only one for which he wrote cadenzas). Throughout the nineteenth century, it was the sole concerto by Mozart that was regularly performed—its demonic power and dark beauty spoke to musicians who had been raised on Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt. -

GEORGIEV Martin

MARTIN GEORGIEV’s artistic activity connects the fields of composition, conducting and research in a symbiosis. As a composer and conductor he has collaborated with leading orchestras and ensembles, such as the Brussels Philharmonic, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Bulgarian National Radio Orchestra, Heidelberg Philharmonic Orchestra, Sofia National Philharmonic Orchestra, National Orchestra of Belgium, Azalea Ensemble, Manson Ensemble, Cosmic Voices choir, Isis Ensemble and Ensemble Musiques Nouvelles. More recently he was Composer in Residence to the City of Heidelberg - 'Komponist für Heidelberg 2012|13", featuring the orchestral commission The Secret which premiered in 2013 with the Heidelberg Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by the composer. Since 2013 he works as Assistant Conductor for the Royal Ballet at ROH Covent Garden, London, where he is involved with a number of world premieres. In 2010-11 he was SAM Embedded Composer with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, London. He has completed a PhD doctorate in Composition at the Royal Academy of Music, University of London (2012), in which he developed his Morphing Modality technique for composition. He also holds Masters' degrees in both Composition and Conducting from the Royal Academy of Music and the National Academy of Music 'Pancho Vladigerov', Sofia, Bulgaria. Born in 1983 at Varna, Bulgaria, he is based in London since 2005, holding both Bulgarian and British citizenship. He is a laureate of the International Composers' Forum TACTUS in Brussels, Belgium, where his works featured in the selection in 2004, 2008 and 2011; the Grand Prize for Symphonic Composition dedicated to the 75th Anniversary of the Sofia National Philharmonic Orchestra in 2003; the UBC Golden Stave Award in 2004; orchestral commission prize in memory of Sir Henry Wood by the Royal Academy of Music, London, in 2011; he was a finalist of the Hindemith Prize of the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival in Germany in 2011 and a recipient of 15 prizes from national and international competitions as a percussionist. -

A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels Achareeya Fukiat Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Fukiat, Achareeya, "A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels" (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5630. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5630 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF SELECTED PIANO CONCERTI FOR ELEMENTARY, INTERMEDIATE, AND EARLY-ADVANCED LEVELS Achareeya Fukiat A Doctoral Research Project submitted to College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance James Miltenberger, -

Ligeti, Gyorgy Lux Aeterna

T.C. DOKUZ EYLÜL ÜNİVERSİTESİ GÜZEL SANATLAR ENSTİTÜSÜ MÜZİK ANASANAT DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ LIGETI, GYORGY LUX AETERNA Hazırlayan Elif Nur KARLIDAĞ Danışman Prof. Dr. Necati GEDİKLİ İZMİR-2007 ÖZGEÇMİŞ Ad, Soyad: Elif Nur KARLIDAĞ Doğum yeri ve yılı: Ankara, 03 Ekim 1982 Yabancı Dil: Fransızca, İngilizce (2006 sınavında TOEFL’dan 220), İtalyanca Eğitimi: Yüksek Lisans: Lisans : Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Devlet Konservatuarı Kompozisyon ve Orkestra Şefliği Anasanat Dalı Kompozisyon Sanat Dalı 2004 mezunu. Lise : İzmir Anadolu Güzel Sanatlar Lisesi Müzik Bölümü 2000 Mezunu. İş tecrübesi: - Mesleki Birlik/Dernek/Kuruluş Üyelikleri: - Alınan Burs ve Ödüller: Eğitim sürecinde Takdirname ve Teşekkürler Yayınları: Başlıca besteleri; Piyano için 3 Pieces, Piyano için 2 Poemes, Piyano için 5 Preludes, 2 Keman için 5 Pieces, Piyano için Variations, Arp ve Flüt için Variations, Piyano için 8 Preludes, Yaylı Çalgılar için‘’Larg Espressivo’’, Piyano için 12 Ton Parçaları, Piyano için 7 Preludes, Piyano için Sonat : 1. Allegro Appassionato 2. Andante 3.Quasi Lullaby 4. Presto, Yaylı Çalgılar Orkestrası için Senfoni ‘’Duvar’’, İki Si bemol Klarinet ve Flüt için ‘’Değişmeyen Eksende Ağır Giden Sezgiler’’, Orkestra ve Koro için Senfoni, Orkestra için Suit, Orkestra için Senfoni Classique, Piyano için Allegro Cantabile, Piyano için Intermezzo, 6 Flüt için Suit. Grafik Notasyon ile yazılmış olan eserler; - Vision (Kuartet için – 2 keman, viyola ve çello), - Değişmeyen Eksende Ağır Giden Önseziler II Soru : Soprano, Arp ve Kontrabas için Cevap : Flüt, Çelesta ve Viyolonsel için, - Koro için ‘’Meditation’’, - Orkestra için ‘’Tranquillo’’ Yüksek Lisans Tezi olarak sunduğum ‘’ LIGETI, GYORGY LUX AETERNA’’ adlı çalışmanın, tarafımdan, bilimsel ahlak ve geleneklere aykırı düşecek bir yardıma başvurmaksızın yazıldığını ve yararlandığım eserlerin bibliyografyada gösterilenlerden oluştuğunu, bunlara atıf yapılarak yararlanılmış olduğunu belirtir ve bunu onurumla doğrularım. -

Discographie

Discographie I. Précurseurs musiques savantes Compilations An Anthology Of Noise & Electronic Music, Vol. 1-5 (Sub Rosa, 2000-2007) Le bruit dans la musique 1900-1950 Compilations Dada et la musique (Centre Georges Pompidou/A&T, 2005) Futurism & Dada Reviewed 1912-1959, (Sub rosa, 1995) Musica Futurista : The Art Of Noise (LTM, 2005) George Antheil, Ballet mécanique, dirigé par Daniel Spalding (Naxos, 2001) Belà Bartók, Le mandarin merveilleux, dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1997) John Cage, Sonatas And Interludes For Prepared Piano, interprété par Boris Berman (Naxos, 1999) John Cage, Imaginary Landscapes, dirigé par Jan Williams (Hat Hut, 1995) Henry Cowell, New Music : Piano Compositions By Henry Cowell, interprété par Sorrel Hays, Joseph Kubera, Sarah Cahill (New Albion Records, 1999) Charles Ives, Symphony n°2 etc., dirigé par Léonard Bernstein (Deutsche Grammophon, 1990) Erik Satie, Parade, dirigé par Manuel Rosenthal (Ades, 2007) Arnold Schoenberg, Pierrot lunaire, Lied der Waldtaube, Erwartung dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Sony, 1993) Edgard Varese, The Complete Works, dirigé par Riccardo Chailly (Decca, 1998) Musique et timbre, 1950 à nos jours Luciano Berio, Differences, Sequenzas III & VII, Due pezzi, Chamber Music (Lilith, 2007) György Ligeti, Requiem, Aventures, Nouvelles Aventures (Wergo, 1985) György Ligeti, Chamber Concerto, Ramifications, String Quartet n°2, Aventures, Lux aeterna, dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1983) Tristan Murail, Gondwana, Désintégrations, Time and Again (Disques Montaigne, 2003) Giacinto Scelsi, The Orchestral Works 2 (Mode, 2006) Krzysztof Penderecki, Anaklasis, Threnody, etc., dirigé par Wanda Wilkomirska (EMI, 1994) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Aus den sieben Tagen (Harmonia Mundi, 1988) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Stimmung (Hyperion, 1986) Iannis Xenakis, Orchestral Works, Vol.