Legislative Assembly Legal and Social Issues Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Nationals Released a Plan

COVID-19 RESPONSE May 2020 michaelobrien.com.au COVID-19 RESPONSE Dear fellow Victorians, By working with the State and Federal Governments, we have all achieved an extraordinary outcome in supressing COVID-19 that makes Victoria – and Australia - the envy of the world. We appreciate everyone who has contributed to this achievement, especially our essential workers. You have our sincere thanks. This achievement, however, has come at a significant cost to our local economy, our community and to our way of life. With COVID-19 now apparently under a measure of control, it is urgent that the Andrews Labor Government puts in place a clear plan that enables us to take back our Michael O’Brien MP lives and rebuild our local communities. Liberal Leader Many hard lessons have been learnt from the virus outbreak; we now need to take action to deal with these shortcomings, such as our relative lack of local manufacturing capacity. The Liberals and Nationals have worked constructively during the virus pandemic to provide positive suggestions, and to hold the Andrews Government to account for its actions. In that same constructive manner we have prepared this Plan: our positive suggestions about what we believe should be the key priorities for the Government in the recovery phase. This is not a plan for the next election; Victorians can’t afford to wait that long. This is our Plan for immediate action by the Andrews Labor Government so that Victoria can rebuild from the damage done by COVID-19 to our jobs, our communities and our lives. These suggestions are necessarily bold and ambitious, because we don’t believe that business as usual is going to be enough to secure our recovery. -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Nos 47, 48 and 49 No 47 — Tuesday 26 November 2019 1 The House met according to the adjournment — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 QUESTION TIME — (Under Sessional Order 9). 3 GREAT OCEAN ROAD AND ENVIRONS PROTECTION BILL 2019 — Ms D’Ambrosio obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to recognise the importance of the landscapes and seascapes along the Great Ocean Road to the economic prosperity and liveability of Victoria and as one living and integrated natural entity for the purposes of protecting the region, to establish a Great Ocean Road Coast and Parks Authority to which various land management responsibilities are to be transferred and to make related and consequential amendments to other Acts and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 4 ROAD SAFETY AND OTHER LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2019 — Ms Neville obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Road Safety Act 1986 to provide for immediate licence or permit suspensions in certain cases and to make consequential and related amendments to that Act and to make minor amendments to the Sentencing Act 1991 and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 5 GENDER EQUALITY BILL 2019 — Ms Williams obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to require the public sector, Councils and universities to promote gender equality, to take positive action towards achieving gender equality, to establish the Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No 101 — Tuesday 4 May 2021 1 The House met according to the adjournment — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 ADDRESS TO HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN — Motion made, by leave, and question — That: (1) The following resolution be agreed to by this House: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN: We, the Legislative Assembly of Victoria, in Parliament assembled, express our sympathy with Your Majesty and members of the Royal Family, in your sorrow at the death of His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh. We acknowledge and pay tribute to his many years of service, and his devoted support of his family. (2) That the following Address to the Governor be agreed to by this House: GOVERNOR: We, the Members of the Legislative Assembly of Victoria, in Parliament assembled, respectfully request that you communicate the accompanying resolution to Her Majesty the Queen (Mr Merlino) — put, after members addressed the House in support of the motion and, members rising in their place to signify their assent, agreed to unanimously. 3 QUESTION TIME — (Under Sessional Order 9). 4 EDUCATION AND TRAINING REFORM AMENDMENT (PROTECTION OF SCHOOL COMMUNITIES) BILL 2021 — Mr Merlino introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 to provide for orders prohibiting or regulating certain conduct on school premises and school-related places and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 5 GAMBLING REGULATION AMENDMENT (WAGERING AND BETTING TAX) BILL 2021 — Mr Pallas introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Gambling Regulation Act 2003 to increase the rate of wagering and betting tax and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY, 20 MARCH 2019 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Education ......................... The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Transport Infrastructure ............................... The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Crime Prevention, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Youth Justice and Minister for Victim Support .................... The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries ............................................ The Hon. MP Foley, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Workplace Safety ................. The Hon. J Hennessy, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Ports and Freight -

Parliament of Victoria

Current Members - 23rd January 2019 Member's Name Contact Information Portfolios Hon The Hon. Daniel Michael 517A Princes Highway, Noble Park, VIC, 3174 Premier Andrews MP (03) 9548 5644 Leader of the Labor Party Member for Mulgrave [email protected] Hon The Hon. James Anthony 1635 Burwood Hwy, Belgrave, VIC, 3160 Minister for Education Merlino MP (03) 9754 5401 Deputy Premier Member for Monbulk [email protected] Deputy Leader of the Labor Party Hon The Hon. Michael Anthony 313-315 Waverley Road, Malvern East, VIC, 3145 Shadow Treasurer O'Brien MP (03) 9576 1850 Shadow Minister for Small Business Member for Malvern [email protected] Leader of the Opposition Leader of the Liberal Party Hon The Hon. Peter Lindsay Walsh 496 High Street, Echuca, VIC, 3564 Shadow Minister for Agriculture MP (03) 5482 2039 Shadow Minister for Regional Victoria and Member for Murray Plains [email protected] Decentralisation Shadow Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Leader of The Nationals Deputy Leader of the Opposition Hon The Hon. Colin William Brooks PO Box 79, Bundoora, VIC Speaker of the Legislative Assembly MP Suite 1, 1320 Plenty Road, Bundoora, VIC, 3083 Member for Bundoora (03) 9467 5657 [email protected] Member's Name Contact Information Portfolios Mr Shaun Leo Leane MLC PO Box 4307, Knox City Centre, VIC President of the Legislative Council Member for Eastern Metropolitan Suite 3, Level 2, 420 Burwood Highway, Wantirna, VIC, 3152 (03) 9887 0255 [email protected] Ms Juliana Marie Addison MP Ground Floor, 17 Lydiard Street North, Ballarat Central, VIC, 3350 Member for Wendouree (03) 5331 1003 [email protected] Hon The Hon. -

Report of the Inquiry Into Anti‑Vilification Protections

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Legal and Social Issues Committee Inquiry into anti‑vilification protections Parliament of Victoria Legislative Assembly Legal and Social Issues Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2021 PP No 207, Session 2018–2021 ISBN 978 1 922425 22 5 (print version), 978 1 922425 23 2 (PDF version) Committee membership CHAIR DEPUTY CHAIR Ms Natalie Suleyman MP Mr James Newbury MP St Albans Brighton Ms Christine Couzens MP Ms Emma Kealy MP Ms Michaela Settle MP Geelong Lowan Buninyong Mr David Southwick MP Mr Meng Heang Tak MP Caulfield Clarinda ii Legislative Assembly Legal and Social Issues Committee About the Committee Functions The Legal and Social Issues Standing Committee is established under the Legislative Assembly Standing Orders Chapter 24—Committees. The Committee’s functions are to inquire into and report on any proposal, matter or thing connected with— • the Department of Health and Human Services • the Department of Justice and Community Safety • the Department of Premier and Cabinet and related agencies. Secretariat Yuki Simmonds, Committee Manager Raylene D’Cruz, Research Officer (until 31 July 2020) Richard Slade, Research Officer (from 9 December 2019) Alice Petrie, Research Officer (from 10 August 2020 to February 2021) Catherine Smith, Administrative Officer (from 18 December 2019 to February 2021) Helen Ross-Soden, Administrative Officer (February 2021) Contact details Address Legislative Assembly Legal and Social Issues Committee Parliament of Victoria Spring Street EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 Phone 61 3 8682 2843 Email [email protected] Web https://parliament.vic.gov.au/lsic-la/inquiries/inquiry/982 This report is available on the Committee’s website. -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No 94 — Friday 19 February 2021 1 The House met in accordance with the terms of the resolution of Wednesday 17 February 2021 — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 DOCUMENTS TABLED UNDER ACTS OF PARLIAMENT — The Clerk tabled the following documents under Acts of Parliament: Municipal Association of Victoria — Report 2019–20 Parliamentary Committees Act 2003 — Government response to the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee’s Report on the 2017–18 and 2018–19 Financial and Performance Outcomes Planning and Environment Act 1987 — Notices of approval of amendments to the following Planning Schemes: Alpine — GC175 Alpine Resorts — GC175 Ararat — GC175 Ballarat — GC175 Banyule — GC175 Bass Coast — GC175 Baw Baw — GC175 Bayside — GC175 Benalla — GC175 Boroondara — GC175 Brimbank — GC175 Buloke — GC175 Campaspe — GC175 Cardinia — C249, GC175 Casey — GC175 Central Goldfields — GC175 Colac Otway — GC175 Corangamite — GC175 Darebin — GC175 East Gippsland — GC175 Frankston — GC175 French Island and Sandstone Island — GC175 Gannawarra — GC175 Glen Eira — GC175 2 Legislative Assembly of Victoria Glenelg — GC175 Golden Plains — GC175 Greater Bendigo — GC175 Greater Dandenong — GC175 Greater Geelong — GC175 Greater Shepparton — GC175 Hepburn — GC175 Hindmarsh — GC175 Hobsons Bay — GC175 Horsham — GC175 Hume — GC175 Indigo — GC175 Kingston — GC175 Knox — GC175 Latrobe — GC175 Loddon — GC175 Macedon Ranges — GC175 Manningham — GC175 Mansfield -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

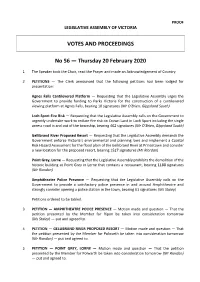

PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No 56 — Thursday 20 February 2020 1 The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 PETITIONS — The Clerk announced that the following petitions had been lodged for presentation: Agnes Falls Cantilevered Platform — Requesting that the Legislative Assembly urges the Government to provide funding to Parks Victoria for the construction of a cantilevered viewing platform at Agnes Falls, bearing 10 signatures (Mr O’Brien, Gippsland South) Loch Sport Fire Risk — Requesting that the Legislative Assembly calls on the Government to urgently undertake work to reduce fire risk on Crown Land in Loch Sport including the single access road in and out of the township, bearing 462 signatures (Mr O’Brien, Gippsland South) Gellibrand River Proposed Resort — Requesting that the Legislative Assembly demands the Government enforce Victoria’s environmental and planning laws and implement a Coastal Risk Hazard Assessment for the flood plain of the Gellibrand River at Princetown and consider a new location for the proposed resort, bearing 1527 signatures (Mr Riordan) Point Grey, Lorne — Requesting that the Legislative Assembly prohibits the demolition of the historic building at Point Grey in Lorne that contains a restaurant, bearing 1188 signatures (Mr Riordan) Amphitheatre Police Presence — Requesting that the Legislative Assembly calls on the Government to provide a satisfactory police presence in and around Amphitheatre and strongly consider opening a police station in the town, bearing 61 signatures (Ms Staley). Petitions ordered to be tabled. 3 PETITION — AMPHITHEATRE POLICE PRESENCE — Motion made and question — That the petition presented by the Member for Ripon be taken into consideration tomorrow (Ms Staley) — put and agreed to. -

Responsibilities of the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee’S Role Is Set out in Legislation

Public Accounts and Estimates Committee About the committee Committee members In 1895 the Victorian Legislative Assembly set up the first Public Accounts Committee in Australia. It was one of the first such Committees in the world. The Committee has a proud tradition of active CHAIR DEPUTY CHAIR oversight. It produces reports that promote Lizzie Blandthorn Richard Riordan public sector reform and accountability. It is Pascoe Vale Polwarth considered the flagship committee of the Victorian Parliament. On behalf of the Parliament, the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee examines public administration and finances to improve outcomes for the Victorian community. Sam Hibbins David Limbrick Gary Maas James Newbury Prahran South Eastern Metropolitan Narre Warren South Brighton Danny O’Brien Pauline Richards Tim Richardson Nina Taylor Gippsland South Cranbourne Mordialloc Southern Metropolitan Public Accounts and Estimates Committee Committee functions Responsibilities of the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee The Public Accounts and Estimates Committee’s role is set out in legislation. It has three main functions – public accounts, estimates and oversight. Public Accounts and Estimates The Committee aims to: Committee (PAEC) 1. Promote public sector accountability Public Accounts Estimates Oversight 2. Deliver reports that promote improvements to public administration and financial management of the State 3. Follow-up on Auditor-General recommendations 4. Ensure the Auditor-General and Parliamentary Budget Officer are accountable and remain Follow up of Victorian Scrutinise budget papers Auditor-General reports (budget estimates) independent 5. Enhance MPs’ understanding and decision making of State financial management matters 6. Contribute to the local and global community of public accounts committees and like agencies Review the outcomes achieved from budget expenditure and revenue raised. -

Membersdirectory.Pdf

The 59th Parliament of Victoria ADDISON, Ms Juliana Wendouree Australian Labor Party Legislative Assembly Parliamentary Service ADDISON, Ms Juliana Elected MLA for Wendouree November 2018. Committee Service Legislative Assembly Economy and Infrastructure Committee since March 2019. Localities with Electorate Localities: Alfredton, Ballarat Central, Ballarat North, Black Hill, Delacombe, Invermay, Invermay Park, Lake Gardens, Nerrina, Newington, Redan, Soldiers Hill and Wendouree. Parts of Bakery Hill, Ballarat East and Brown Hill., Election Area km2: 114 Electorate Office Address Ground Floor, 17 Lydiard Street North Ballarat Central VIC 3350 Telephone (03) 5331 1003 Email [email protected] Facebook www.facebook.com/JulianaAddisonMP Twitter https://twitter.com/juliana_addison Website www.JulianaAddison.com.au ALLAN, The Hon Jacinta Bendigo East Australian Labor Party Legislative Assembly Minister for Transport Infrastructure Minister for the Coordination of Transport: COVID-19 Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop Priority Precincts March 2020 - June 2020. Minister for the Parliamentary Service ALLAN, The Hon Jacinta Elected MLA for Bendigo East September 1999. Re-elected Coordination of Transport: COVID-19 since April 2020. November 2002, November 2006, November 2010, Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop since June 2020. November 2014, November 2018. ; Party Positions Parliamentary Party Position Delegate, Young Labor Conference 1993-95. Secretary, Leader of the House since December 2014. Manager of Bendigo South Branch 1994. Secretary 1995-97, Pres. 1997- Opposition Business since December 2010. 2000, Bendigo Federal Electorate Assembly. Committee Service Personal Dispute Resolution Committee since February 2019. Born Bendigo, Victoria, Australia.Married, two children. Legislative Assembly Privileges Committee since February Education and Qualifications 2019. Legislative Assembly Standing Orders Committee BA(Hons) 1995 (La Trobe). -

The 2018 Victorian State Election

The 2018 Victorian State Election Research Paper No. 2, June 2019 Bella Lesman, Alice Petrie, Debra Reeves, Caley Otter Holly Mclean, Marianne Aroozoo and Jon Breukel Research & Inquiries Unit Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank their colleague in the Research & Inquiries Service, Meghan Bosanko for opinion poll graphs and the checking of the statistical tables. Thanks also to Paul Thornton-Smith and the Victorian Electoral Commission for permission to reproduce their election results maps and for their two-candidate preferred results. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) Research Paper: No. 2, June 2019. © 2019 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the Library, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria. All other material produced by the Parliament of Victoria is copyright. If you are unsure please contact us. -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Nos 60, 61 and 62 No 60 — Tuesday 17 March 2020 1 The House met according to the adjournment — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 QUESTION TIME — (Under Sessional Order 9). 3 CONSTITUTION AMENDMENT (FRACKING BAN) BILL 2020 — Mr Pallas introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Constitution Act 1975 to constrain the power of the Parliament to make laws repealing, altering or varying certain provisions that prohibit hydraulic fracturing and coal seam gas exploration and mining and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 4 PETROLEUM LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2020 — Mr Pallas introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Petroleum Act 1998 and the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2010 and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 5 CRIMES (MENTAL IMPAIRMENT AND UNFITNESS TO BE TRIED) AMENDMENT BILL 2020 — Ms Hennessy introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 to implement recommendations of the Victorian Law Reform Commission arising from its review of that Act, to amend that Act and the Mental Health Act 2014 to transfer functions of the Forensic Leave Panel to the Mental Health Tribunal, to amend the Disability Act 2006 in relation to custodial supervision orders, to consequentially amend other Acts and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow.