ART and CRAFT Directed by Sam Cullman and Jennifer Grausman Co-Directed by Mark Becker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2014 Kress Foundation Department of Art History

Newsletter Fall 2014 Kress Foundation Department of Art History 1301 Mississippi Street, 209 Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kansas 66045 phone: 785-864-4713 F email: [email protected] F web: arthistory.ku.edu From The Chair This year the Art History Department was pleased to honor Corine Wegener as the recipient of the 2014 Franklin D. Murphy Distinguished Alumni Award. Cori received a Master’s degree first in Political Science from the University of Kansas in CONTENTS 1994, and in 2000 obtained her Master’s degree from KU in the History of Art. From 1999—just before she completed her History of Art Master’s degree—to From The Chair 1 2012, Cori enjoyed an impressive career trajectory at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. In their Department of Decorative Arts, Textiles and Sculptures, she began as With Thanks 4 a Curatorial Intern and was subsequently hired as a Research Assistant, then Assis- tant Curator, and finally Associate Curator. In these roles, Cori was responsible for 2014 Murphy 5 the acquisition, conservation, exhibition, and educa- Lecture Series tional programs related to American and European New Faculty 7 decorative arts. Meanwhile, from 1982 through 2004, Cori assumed Faculty News 8 the responsibilities as a Major (now retired) in the U.S. Army Reserve. These years were concurrent Alumni News 15 with the time she spent as an undergrad and grad- uate student, and also concurrent with her cura- Graduate Student 20 torial career at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. News Cori’s mobilizations in the U.S. Army Reserve took Congratulations 22 her to Germany, Guam, Bosnia and Iraq. -

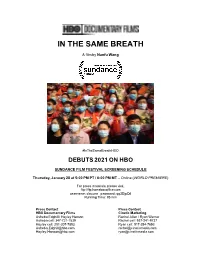

In the Same Breath

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

Sturm Und Drang : JONAS BURGERT at BLAIN SOUTHERN GALLERY DAFYDD JONES : JONAS BURGERT at JONAS BURGERT I BERLIN

FREE 16 HOT & COOL ART : JONAS BURGERT AT BLAIN SOUTHERN GALLERY : JONAS BURGERT AT Sturm und Drang DAFYDD JONES JONAS BURGERT I BERLIN STATE 11 www.state-media.com 1 THE ARCHERS OF LIGHT 8 JAN - 12 FEB 2015 ALBERTO BIASI | WALDEMAR CORDEIRO | CARLOS CRUZ-DÍEZ | ALMIR MAVIGNIER FRANÇOIS MORELLET | TURI SIMETI | LUIS TOMASELLO | NANDA VIGO Luis Tomasello (b. 1915 La Plata, Argentina - d. 2014 Paris, France) Atmosphère chromoplastique N.1016, 2012, Acrylic on wood, 50 x 50 x 7 cm, 19 5/8 x 19 5/8 x 2 3/4 inches THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING: 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ CAREL VISSER, 18 FEB - 10 APR 2015 TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com JAN_AD(STATE).indd 1 03/12/2014 10:44 WiderbergAd.State3.awk.indd 1 09/12/2014 13:19 rosenfeld porcini 6th febraury - 21st march 2015 Ali BAnisAdr 11 February – 21 March 2015 4 Hanover Square London, W1S 1BP Monday – Friday: 10.00 – 18.00 Saturday: 10.00 – 17.0 0 www.blainsouthern.com +44 (0)207 493 4492 >> DIARY NOTES COVER IMAGE ALL THE FUN OF THE FAIR IT IS A FACT that the creeping stereotyped by the Wall Street hedge-fund supremo or Dafydd Jones dominance of the art fair in media tycoon, is time-poor and no scholar of art history Jonas Burgert, 2014 the business of trading art and outside of auction records. The art fair is essentially a Photographed at Blain|Southern artists is becoming a hot issue. -

Hiff 25 Awards Announced

1 THE 25TH HAMPTONS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES HIFF AWARD WINNERS FOR BEST NARRATIVE FEATURE AND BEST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE UNDER THE TREE AND LOTS OF KIDS, A MONKEY AND A CASTLE Julie Andrews, Dick Cavett and Patrick Stewart Honored at Festival East Hampton, NY (October 9, 2017) – The 25th Hamptons International Film Festival today announced their award winners at a ceremony in East Hampton. UNDER THE TREE, directed by Hafsteinn Gunnar Sigurðsson won the Award for Best Narrative Feature. LOTS OF KIDS, A MONKEY AND A CASTLE, directed by Gustavo Salmerón, received the Award for Best Documentary Feature, sponsored by ID Films. DEKALB ELEMENTARY, directed by Reed Van Dyk, and EDITH+EDDIE, directed by Laura Checkoway, received the Award for Best Narrative Short Film and for Best Documentary Short Film, respectively. COMMODITY CITY, directed by Jessica Kingdon, received an Honorable Mention for Documentary Short Film. The Tangerine Entertainment Juice Fund Award was awarded to NOVITIATE, directed by Maggie Betts. This award honors an outstanding female narrative filmmaker. WANDERLAND, directed by Josh Klausner, was awarded the Suffolk County Next Exposure Grant. This program supports the completion of high quality, original, director-driven, low- budget independent films from both emerging and established filmmakers who have completed 50% of principal photography within Suffolk County. The film was awarded a $3,000 grant. HONDROS, directed by Greg Campbell, was awarded the 2017 Brizzolara Family Foundation Award for a Film of Conflict and Resolution, sponsored by HighTower Sports and Entertainment. THE LAST PIG, directed by Allison Argo, was awarded the Zelda Penzel Giving Voice to the Voiceless Award. -

Sundance Institute to Present a Week of Creative Film Producing Initiatives, July 29 – August 4, 2013

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: July 17, 2013 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute to Present a Week of Creative Film Producing Initiatives, July 29 – August 4, 2013 11 Projects Selected for Creative Producing Labs, Ongoing Support and Granting; 40 Industry Leaders Converge for Creative Producing Summit Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute today announced the participants for its annual Creative Producing Labs and Creative Producing Summit, both held the week of July 29 at the Sundance Resort in Sundance, Utah. These activities are part of the Institute’s year-round Creative Producing Initiative, which encompasses a series of Labs, Fellowships and other events that support independent producers. Eleven projects will participate in the Labs (July 29 – August 2), where they will work with an accomplished group of Creative Advisors to advance their creative, communication and problem-solving skills in all stages of a film’s journey from script development to distribution. These Producing Fellows will also receive ongoing creative and strategic support throughout the year, as well as direct granting for further development and production. This year’s Fellows represent eleven projects identified by the Institute’s Feature Film Program and Documentary Film Program and Fund. Immediately following the Labs, the Summit (August 2-4) takes place. The Summit is an invitation-only gathering that connects 42 producers and directors, including the Producing Fellows, with more than 40 top independent film industry leaders for three days of case study sessions, panels, roundtable discussions, one-on-one meetings and pitching sessions. Multimedia artist Doug Aitken, whose installation Sleepwalkers was featured in New Frontier at the Sundance Film Festival, will deliver a keynote opening address on storytelling and the creative process. -

Lead Ing Creative Ly Sep

LEAD ING 2012 CONFERENCE CREATIVE LY MINNEAPOLIS, MN SEP 6–8 NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MEDIA ARTS + CULTURE NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MEDIA ARTS + CULTURE LEAD ING 2012 CONFERENCE CREATIVE LY MINNEAPOLIS, MN SEP 6–8 We wish to inspire, illuminate, and activate you so that you can return to your communities reinvigorated. As a network, we flourish on the exchangeNATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MEDIA ARTS of + CULTURE ideas and on collaboration. NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MEDIA ARTS + CULTURE TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome 2 Credits 6 Official Proclamation Letter 7 General Information 9 Awards 10 Plenary Sessions 16 Locally Sourced Events 20 Expo 26 Schedule at a Glance 28 Documentary Screening Program 30 Schedule in Detail and Map 35 1 WELCOME! In 2010, NAMAC took The Twin Cities have long been at the forefront of cre- on issues of devel- ative placemaking. Through municipal and regional oping leadership planning, philanthropic initiatives, and public–private and building orga- partnerships, Minneapolis and St. Paul serve as re- nizational capac- gional models for community building, integrating the ity across the me- arts into community life. We look to the way the Twin dia arts field in our Cities’ cultural landscape continues to be shaped by publication Lead- policies that support artists’ live-work neighborhoods; ing Creatively. Now, private and corporate foundations funding both artists with our National and innovative community projects; and waves of im- Conference, Lead- migrants who bring vital energy and ideas to the cul- ing Creatively, we’re tural environment. The recent voter-approved Minne- bringing this work sota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund legislates new up to date and ex- tax revenues for clean water, parks and recreation tending it for today’s challenges. -

Interfaces Contemporâneas No Ecossistema Midiático

Interfaces Contemporâneas no Ecossistema Midiático Taciana Burgos Rodrigo Cunha Organizadores Prefácio de Carlos A. Scolari Ria Editorial - Comité Científico Abel Suing (UTPL, Equador) Alfredo Caminos (Universidade Nacional de Cordoba, Argentina) Andrea Versutti (UnB, Brasil) Angela Grossi de Carvalho (Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, Brasil) Angelo Sottovia Aranha (Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, Brasil) Anton Szomolányi (Pan-European University, Eslováquia) Antonio Francisco Magnoni (Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, Brasil) Carlos Arcila (Universidade de Salamanca, Espanha) Catalina Mier (UTPL, Equador) Denis Porto Renó (Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, Brasil) Diana Rivera (UTPL, Equador) Fatima Martínez (Universidade do Rosário, Colômbia) Fernando Ramos (Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal) Fernando Gutierrez (ITESM, México) Fernando Irigaray (Universidade Nacional de Rosario, Argentina) Gabriela Coronel (UTPL, Equador) Gerson Martins (Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul – UFMS, Brasil) Hernán Yaguana (UTPL, Equador) Jenny Yaguache (UTPL, Equador) Jerónimo Rivera (Universidade La Sabana, Colombia) Jesús Flores Vivar (Universidade Complutense de Madrid, Espanha) João Canavilhas (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) John Pavlik (Rutgers University, Estados Unidos) Joseph Straubhaar (Universidade do Texas – Austin, Estados Unidos) Juliana Colussi (Universidade do Rosário, Colômbia) Koldo Meso (Universidade do País Vasco, Espanha) Lorenzo Vilches (Universidade Autônoma de Barcelona, Espanha) Lionel -

84Th ACADEMY AWARDS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED

MEDIA CONTACT Teni Melidonian [email protected] Toni Thompson [email protected] January 24, 2012 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 84th ACADEMY AWARDS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED BEVERLY HILLS, CA — Nominations for the 84th Academy Awards were announced today (Tuesday, January 24) by Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences President Tom Sherak and 2010 Oscar® nominee Jennifer Lawrence. Sherak and Lawrence, who was nominated for an Academy Award® for her lead performance in “Winter’s Bone,” announced the nominees in 10 of the 24 Award categories at a 5:38 a.m. PT live news conference attended by more than 400 international media representatives. Lists of nominations in all categories were then distributed to the media in attendance and online via the official Academy Awards website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominations are selected by vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Nominations ballots were mailed to the 5,783 voting members in late December and were returned directly to PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), the international accounting firm, for tabulation. Official screenings of all motion pictures with one or more nominations will begin for members this weekend at the Academy's Samuel Goldwyn Theater. Screenings also will be held at the Academy's Linwood Dunn Theater in Hollywood and in London, New York and the San Francisco Bay Area. All active and life members of the Academy are eligible to select the winners in all categories, although in five of them – Animated Short Film, Live Action Short Film, Documentary Feature, Documentary Short Subject and Foreign Language Film – members can vote only if they have seen all of the nominated films in those categories. -

“Oscar ® ” and “Academyawards

“OSCAR®” AND “ACADEMY AWARDS®” ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF THE ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES, AND USED WITH PERMISSION. THIS IS NOT AN ACADEMY RELEASE. A SISTER BELGIUM /16MINS/2018 Native Title: UNE SOEUR Director: DElphiNE GiRaRD Producers: JacqUES-hENRi BRONckaRt (VERSUS pRODUctiON) Synopsis: a night. a car. alie is in trouble. to get by she must make the most important call of her life. Director’s Biography: Born in the heart of the French-canadian winter, Delphine Girard moved to Belgium a few years later. after starting her studies as an actress, she transferred to the directing department at the iNSaS in Brussels. her graduation film, MONSTRE , won several awards in Belgium and around the world. after leaving the school, she worked on several films as an assistant director, children's coach or casting director ("Our children" by Joachim lafosse, "Mothers’ instinct" by Olivier Masset-Depasse) while writing and directing the short film CAVERNE , adapted from a short story by the american author holly Goddard Jones. A SISTER is her second short film. She is currently working on her first feature and a fiction series. Awards: Jury Prize - Saguenay IFF (Canada) Grand Prize Rhode Island IFF (USA) Best International Short Film Sulmona IFF (Italy) Grand Prize Jury SPASM Festival (Canada) Best Short Film, Public Prize, Be tv Prize, University of Namur Prize - Namur Film Festival (Belgium) Public Prize & Special mention by press - BSFF (Belgium) Best Belgian Short Film RamDam FF (Belgium) Prize Creteil Film Festival Festivals/Screenings: -

Size, Scale and the Imaginary in the Work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim

Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim © Michael Albert Hedger A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History and Art Education UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES | Art & Design August 2014 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hedger First name: Michael Other name/s: Albert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Ph.D. School: Art History and Education Faculty: Art & Design Title: Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Conventionally understood to be gigantic interventions in remote sites such as the deserts of Utah and Nevada, and packed with characteristics of "romance", "adventure" and "masculinity", Land Art (as this thesis shows) is a far more nuanced phenomenon. Through an examination of the work of three seminal artists: Michael Heizer (b. 1944), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) and Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the thesis argues for an expanded reading of Land Art; one that recognizes the significance of size and scale but which takes a new view of these essential elements. This is achieved first by the introduction of the "imaginary" into the discourse on Land Art through two major literary texts, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias (1818)- works that, in addition to size and scale, negotiate presence and absence, the whimsical and fantastic, longevity and death, in ways that strongly resonate with Heizer, De Maria and especially Oppenheim. -

The Best of Hot Docs 2011

The Best of Hot Docs 2011 A doc-lovers’ guide to this year’s festival must-sees BY Jason Anderson and Adam Nayman, April 28, 2011 http://www.eyeweekly.com/film/feature/article/114730--the-best-of-hot-docs-2011 Beauty Day BIG BUZZ FLICKS PROJECT NIM ***** Dir. James Marsh. 93 min The director of Man on Wire returns with something just as astonishing as his Oscar winner. In place of high-wire artist Philippe Petit we have Nim, a chimp raised by humans and taught sign language as part of an experiment by an ambitious Columbia University professor in the 1970s. Loaded with ethical and moral quandaries, the saga is gripping, bizarre and dispiriting in its illustration of the inhumanity of people’s attitudes, to other species and our own. May 5, 9:45pm and May 6, 11am, Isabel Bader. JA BUCK **** Dir. Cindy Meehl. 88 min This Sundance prizewinner is a superior brand of horse tale. Often seeming more like a Zen master than an animal trainer, Buck Brannaman spends his life showing folks a kinder, gentler way of handling even their most skittish colts. The Montana cowboy’s sensitivity and soulfulness is all the more affecting when Cindy Meehl’s film reveals the horrific circumstances of Brannaman’s own early years. May 3, 6:30pm, Bloor; May 5, 1:15pm and May 8, 4:15pm, Isabel Bader. JA BEAUTY DAY **** Dir. Jay Cheel. 90 min If only there’d been a YouTube back when a St. Catharines hoser named Ralph Zavadil was thrilling local cable viewers with the very foolhardy stunts he performed in the guise of Cap’n Video. -

89Th Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Academy Publicity [email protected] January 24, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Editor’s Note: Nominations press kit and video content available here 89TH OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED LOS ANGELES, CA — Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, joined by Oscar®-winning and nominated Academy members Demian Bichir, Dustin Lance Black, Glenn Close, Guillermo del Toro, Marcia Gay Harden, Terrence Howard, Jennifer Hudson, Brie Larson, Jason Reitman, Gabourey Sidibe and Ken Watanabe, announced the 89th Academy Awards® nominations today (January 24). This year’s nominations were announced in a pre-taped video package at 5:18 a.m. PT via a global live stream on Oscar.com, Oscars.org and the Academy’s digital platforms; a satellite feed and broadcast media. In keeping with tradition, PwC delivered the Oscars nominations list to the Academy on the evening of January 23. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 24 categories beginning Monday, February 13 through Tuesday, February 21. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 89th Oscars will be held on Sunday, February 26, 2017, at the Dolby Theatre® at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live on the ABC Television Network at 7 p.m.