Robinson Jeffers - Poems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetry of Robinson Jeffers

The Poetry of Robinson Jeffers 1 Table of Contents The Poetry of Robinson Jeffers About the Book.................................................... 3 “Permanent things, About the Author ................................................. 4 or things forever Historical and Literary Context .............................. 7 Other Works/Adaptations ..................................... 8 renewed, like the Discussion Questions............................................ 9 grass and human Additional Resources .......................................... 10 passions, are the Credits .............................................................. 11 material for poetry...” Preface The poetry of Robinson Jeffers is emotionally direct, magnificently musical, and philosophically profound. No one has ever written more powerfully about the natural beauty of the American West. Determined to write a truthful poetry purged of ephemeral things, Jeffers cultivated a style at What is the NEA Big Read? once lyrical, tough-minded, and timeless. A program of the National Endowment for the Arts, NEA Big Read broadens our understanding of our world, our communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a good book. Managed by Arts Midwest, this initiative offers grants to support innovative community reading programs designed around a single book. A great book combines enrichment with enchantment. It awakens our imagination and enlarges our humanity. It can offer harrowing insights that somehow console and comfort us. Whether you’re a regular reader already or making up for lost time, thank you for joining the NEA Big Read. NEA Big Read The National Endowment for the Arts 2 About the Book Introduction to Robinson Jeffers The poetry of Robinson Jeffers is distractingly memorable, not only for its strong music, but also for the hard edge of its wisdom. His verse, especially the wild, expansive narratives that made him famous in the 1920s, does not fit into the conventional definitions of modern American poetry. -

The Works of William Cowper, Esq., Comprising His Poems, Correspondence, and Translations

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com TheWorksofWilliamCowper,Esq.,ComprisingHisPoems,Correspondence,andTranslations WilliamCowper,RobertSouthey mt / * r SI \/,V I M C©7. '. / ///; ivHHi" *i-;Avt-h r " ] )' HP* II", - i.; ,-. i" / .: >IF r 'Hl'l " t* J-.li /. h v i WILLIAM f f ti 1' *. v , . or, k 'i'r .so h'i' i '.' v V rJ L , V 1 I: » .. •!i.!":"ta!J'S!t BA' rcwi! "' «.- . IMM'v „ pa l f J 3 la . THE WORKS or WILLIAM COWPER, Esq. COMPRISING HIS POEMS, CORRESPONDENCE, AND TRANSLATIONS. WITH A LIFE OF THE AUTHOR, BY THE EDITOR, ROBERT SOUTHEY, Esq. LL. D. POET LAUREATE, ETC. VOL. VIII. LONDON: BALDWIN AND CRADOCK, PATERNOSTER ROW. 1836. CHISWICK press: C. WHITTINGHAM, COLLEGE HOUSE. WZoo ADVERTISEMENT. I. This Volume contains such of Cowper's juvenile Poems as were published by Hayley, those which Mr. Croft published under the title of Early Pro ductions, Cowper's part of the Olney Hymns, the Anti-Thelyphthora, and the volume of Poems by which, in 1782, he first made himself known to the public. 2. The pieces introduced by Hayley in his Life of the Poet, or appended to it, were either obtained from Cowper and Lady Hesketh, or pointed out to him by their author in the books wherein they had been pub lished anonymously. 3. Mr. Croft's little, but most interesting volume appeared with the following title, dedication, and pre face. -

Welcome to the Great Ring

Planescape Campaign Setting Chapter 1: Introduction Introduction Project Managers Ken Marable Gabriel Sorrel Editors Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Writers Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Layout Sarah Hood 1 There hardly seem any words capable of expressing the years of hard work and devotion that brings this book to you today, so I will simply begin with “Welcome to the planes”. Let this book be your doorway and guide to the multiverse, a place of untold mysteries, wonders the likes of which are only spoken of in legend, and adventurers that take you from the lowest depths of Hell to the highest reaches of Heaven. Here in you will leave behind the confines and trappings of a single world in order to embrace the potential of infinity and the ability to travel Introduction wherever you please. All roads lie open to planewalkers brave enough to explore the multiverse, and soon you will be facing wonders no ordinary adventure could encompass. Consider this a step forward in your gaming development as well, for here we look beyond tales of simple dungeon crawling to the concepts and forces that move worlds, make gods, and give each of us something to live for. The struggles that define existence and bring opposing worlds together will be laid out before you so that you may choose how to shape conflicts that touch millions of lives. Even when the line between good and evil, lawful and chaotic, is as clear as the boundaries between neighboring planes, nothing is black and white, with dark tyrants and benevolent kings joining forces to stop the spread of anarchy, or noble and peasant sitting together in the same hall to discuss shared philosophy. -

Kant, Mission Command, and What It Means to Take

OPERATIONALIZING A PEOPLE-FIRST STRATEGY: KANT, MISSION COMMAND, AND WHAT IT MEANS TO TAKE RESPONSIBILITY IN A 21ST CENTURY MILITARY A Thesis by JON GENE THOMPSON, JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Kristi Sweet Committee Members, Theodore George Marian Eide Head of Department, Theodore George May 2021 Major Subject: Philosophy Copyright 2021 Jon Gene Thompson, Jr. ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to argue for the adoption of Mission Command because it stands to promote the kind of functioning proper to the aims and conditions of the increasingly tech-enabled military. It does this because there are no mission, battle, or war conditions where good judgment and responsible action are not critical to the success of the military’s endeavors. In this, there is a moral basis to the proper functioning of a good military – trust and responsibility taking. While some argue that implementing Mission Command is infeasible, I argue that Kant, in fact, provides a model of moral education that suits Mission Command’s integration quite well. I turn to Kant because he is the thinker for whom responsibility is the key concept, so his thoughts on how to cultivate it are relevant to the successful integration of Mission Command. In order to support my argument for Mission Command, I first focus the thesis on the ethical debates of autonomous weapons systems (AWS), specifically, drones. In finding the literature too narrow, I argue the ethical discussion must be recast in terms of judgment, autonomy, and responsibility in order to locate a balanced path forward for the ethical research and development of technology that privileges the centrality of the human agent. -

Planescape Part One: Sigil by Cutter

Planescape Part One: Sigil By Cutter Welcome to Sigil, the City of Doors! The centre of the Planes and the local multiverse too. Sitting on the inside of a giant torus that itself floats above an infinitely tall mountain at the centre of the very plane of neutrality itself – the Concordant Domains of the Outlands. Here neutrality is enforced. Gods are barred from the city, and the Lady of Pain takes very aggressive steps to make sure nobody drags Sigil into the troubles outside. It is even a haven from the Blood War. Unfortunately, this means many, many criminals and troublemakers from outside land come here as a last resort. ‘Course, not everyone’s here of their own free choice. Sigil’s ridded in doors to other planes, and sometimes a local from outside falls in. What got them in Sigil rarely is what gets them out of Sigil, and they’re stuck here until they find a door back home. These planar doors all throughout Sigil would make it the most valuable place in the multiverse to hold. Master Sigil, you can master the Planes. But the Lady won’t let that happen. Piss her off and the best thing you can hope for is being locked in an extradimensional maze unable to die of age, hunger, or thirst. The unlucky ones get flayed alive in an instant. But on the bright side, you’ll see all kinds of things in Sigil. A devil and a demon (don’t call ‘em that, trust me) having friendly drinks in a bar. -

Beware, Red Heads Don't Numb!

Research Article Published: 08 Mar, 2019 Journal of Ophthalmology Forecast Beware, Red Heads Don’t Numb! Matthews JM*, Petrykowski B and Davidorf F Havener Eye Institute, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, USA Abstract Background: The use of topical anesthesia in the outpatient setting by Ophthalmologists has seen a dramatic increase since the development of antivegf medications. Each year, there are an estimated 6-7 million anti-vegf injections performed in the United States. People with red hair have a mutation of the MC1R gene, which has been associated with decreased effectiveness of local anesthesia. The purpose of this communication is to alert the ophthalmology community of potential for inadequate anesthesia for intraocular injections Methods: IRB was obtained through OSU IRB. 175 patients receiving intravitreal injections were randomly surveyed to determine incidence of poor analgesia with injections. Results: Overall, 19/175 patients were found to have decreased effectiveness of local anesthesia. We found a surprisingly high incidence (10.5%) of patients who require increased amounts of local anesthesia than is commonly used in those with natural red/auburn hair. Conclusion: We encourage ophthalmologists who use local anesthesia for their patients to include an assessment of their response to dental anesthesia. These individuals need to be identified who have had previously bad experiences with poor responses to local anesthesia. We recommend using twice the amount of topical anesthesia in these patients. Keywords: Intravitreal injections; MC1R Gene; Red hair; VEGF; Topical anesthesia Introduction The use of topical anesthesia in the outpatient setting by Ophthalmologists has seen a dramatic increase since the development of antivegf medications. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 5, No. 1

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 5 . NUMBER 1 SPECIAL ISSUE ON MELODRAMA AND CINEMA Editor's Note I Melodrama/Subjectivity/Ideology: The Relevance of Western Melodrama Theories to Recent Chinese Cinema 6 E. ANN KAPLAN Melodrama, Postmodernism, and the Japanese Cinema MITSUHIRO YOSHIMOTO Negotiating the Transition to Capitalism: The Case of Andaz 56 PAUL WILLEMEN The Politics of Melodrama in Indonesian Cinema KRISHNA SEN Melodrama as It (Dis)appears in Australian Film SUSAN DERMODY Filming "New Seoul": Melodramatic Constructions of the Subject in Spinning Wheel and First Son 107 ROB WILSON Psyches, Ideologies, and Melodrama: The United States and Japan 118 MAUREEN TURIM JANUARY 1991 The East-West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Editor's Note UNTIL very recent times, the term melodrama was used pejoratively to typify inferior works of art that subscribed to an aesthetic of hyperbole and that were given to sensationalism and the crude manipulation of the audiences' emotions. However, during the last fifteen years or so, there has been a distinct rehabilitation of the term consequent upon a retheoriz ing of such questions as the nature of representation in cinema, the role of ideology, and female subjectivity in films. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

Chicano Nationalism: the Brown Berets

CHICANO NATIONALISM: THE BROWN BERETS AND LEGAL SOCIAL CONTROL By JENNIFER G. CORREA Bachelor of Science in Criminology Texas A&M University Kingsville, TX 2004 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July 2006 CHICANO NATIONALISM: THE BROWN BERETS AND LEGAL SOCIAL CONTROL Thesis Approved: Dr. Thomas Shriver Thesis Adviser Dr. Gary Webb Dr. Stephen Perkins Dr. A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1 II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE ………………………………………………………7 Informants and Agent Provocateurs .........................................................................8 Surveillance, Dossiers, Mail Openings, and Surreptitious Entries ……………….14 Violent Strategies and Tactics ……………………………………………………20 III. METHOD OLOGY……………………………………………………………….29 Document Analysis ................................................................................................30 Telephone Interviews .............................................................................................32 Historical Analysis .................................................................................................34 IV. FINDINGS .............................................................................................................36 Mexican -American History ...................................................................................36 -

4 Minutes Remix Avant

4 minutes remix avant click here to download 4 Minutes (Mr. ColliPark Remix) Lyrics:: / Y'all know what time it is when you hear that siren! It's the ColliPark Remix. Yo Avant! Let's beat they back out /: / I only. 4 Minutes (Remix) by Avant feat. Krayzie Bone, Shawnna and Layzie Bone - discover this song's samples, covers and remixes on WhoSampled. Oct 9, Stream Avant Featuring Bone T - 4 Minutes Remix by aysmusic from desktop or your mobile device. Find a Avant (2) - 4 Minutes - (Collipark Remix) first pressing or reissue. Complete your Avant (2) collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Avant - 4 Minutes Remix lyrics lyrics: Clock ticking) Yall know what time it is its the collipark remix lil bun lets beat they back out. track listing: 4 Minutes collipark remix feat. KRAYZIE BONE & SHAWNNA & LAYZIE BONE main /instrum. /clean /instrum. /acapella Read about 4 Minutes (Remix) (Feat. Bone Thugs-N-Harmony & Shawnna) by Avant and see the artwork, lyrics and similar artists. Read about 4 Minutes (Remix) ft. Bone Thugs-N- Harmony & Shawnna by Avant and see the artwork, lyrics and similar artists. (Clock ticking) Yall know what time it is its the collipark remix lil bun lets beat they back out (Avant) i only got 4 minutes to do what i gotta do to prove to you. Myron Avant (born April 26, ), better known as Avant, is an American R&B singer/songwriter. He is best known for hits such as "Separated" (the remix to. 4 minutes (collipark remix) from avant () (12''). And other albums from avant are available on sale at Recordsale. -

![The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9514/the-canon-1972-73-volume-3-number-4-649514.webp)

The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4

Digital Collections @ Dordt Dordt Canon University Publications 1973 The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4 Dordt College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/dordt_canon Recommended Citation Dordt College, "The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4" (1973). Dordt Canon. 55. https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/dordt_canon/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dordt Canon by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soli Deo Gloria CANNON DORDT COLLEGE, SIOUX CENTER, IOWA VOL. III -.- No.4 Mother Night: Victims of Change Victoria and Blue·Jeans Prof. James Koldenhoven by Pat De Young What Is Life? The old and the new, like jaws of a trap, have closed on the people of I saw Victoria Allison for the first ally she disagreed in discussion-too by Becky Maatman Tennessee Williams and John Osborne's time on satge. She walked out, long loudly in her curt, clipped Yankee ac- Vonnegut, author of Mother Night plays, The Glass Menagerie and Look swinging steps, took the mike, and cent. Having said what she wanted to asks, "What is a war criminal? Is it Back inAnger. Laura Wingfield iS1he quietly announced, "I will sing a selec- say, she would give her head a toss someone who has obeyed his conscience, central victim in Williams' American tion from Hair." Staring at the floor in and return to silence, eyes focused on perhaps doing wrong,",» is it someone (U.S.A.) culture in the 1930's and silence, she paused. -

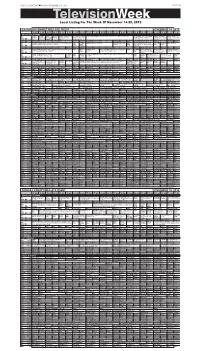

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of November 14-20, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of November 14-20, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 14, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Cook’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel Songs The Lawrence Welk High School Football SDHSAA Class 11AAA, Final: Teams TBA. (N) (Live) Rock Garden Tour: Soul Butter Austin City Limits Globe Trekker The PBS Country Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd of patriotism and Show California vaca- and Hogwash (In Stereo) Å “James Taylor” (N) (In history of tea; cultural KUSD ^ 8 ^ Å Garden faith. Å tion destinations. Stereo) Å traditions. KTIV $ 4 $ College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. (N) Å News 4 Insider Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live News 4 Saturday Night Live (N) Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. From Notre Dame Sta- KDLT The Big Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live KDLT Saturday Night Live Elizabeth The Simp- The Simp- KDLT News Å NBC dium in South Bend, Ind. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å News Bang (In Stereo) Å News Banks; Disclosure performs. (N) (In sons sons KDLT % 5 % (N) Å Theory (N) Å Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) College Football Michigan at Indiana. (N) (Live) Score News Edition College Football Oklahoma at Baylor.