Dating Danish Textiles and Skins from Bog Finds by Means of 14C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bog Bodies & Their Biochemical Clues

May 2018 cchheemmiissin Auttstrrraliayy Bog bodies & their biochemical clues chemaust.raci.org.au • Spider venoms as drenching agents • Surface coatings from concept to commercial reality • The p-value: a misunderstood research concept SBtioll ghe rbe odies in the hereafter n 13 May 1983, the Bog bodies such as Tollund Man partially preserved head provide a fascinating insight into of a woman was Odiscovered buried in biochemical action below the ground. peat at Lindow Moss, near Wilmslow in Cheshire, England. Police BY DAVE SAMMUT AND suspected a local man, Peter Reyn- Bardt, whose wife had gone missing CHANTELLE CRAIG two decades before .‘It has been so long, I thought I would never be Toraigh Watson found out’, confesse dReyn- Bardt under questioning. He explained how he had murdered his wife, dismembered her body and buried the pieces near the peat bog. Before the case could go to trial, carbon dating of the remains showed that the skull was around 17 centuries CC-PD-Mark old. Reyn- Bardt tried to revoke his confession, but was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment . Lindow Woman and other ‘bog bodies’, as they have come to be known, are surprisingly common. Under just the right set of natural conditions, human remains can be exceptionally well preserved for extraordinarily long periods of time. 18 | Chemistry in Australia May 2018 When bog water beats bacteri a Records of bog bodies go back as far as the 17th century, with a bod y discovered at Shalkholz Fen in Holstein, Germany. Bog bodies are most commonly found in northwestern Europe – Denmark, the Netherlands, Ireland, Great Britain and northern Germany. -

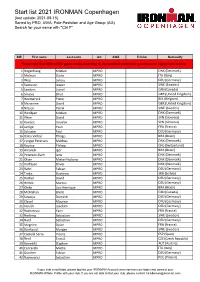

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

Oversigt Over Retskredsnumre

Oversigt over retskredsnumre I forbindelse med retskredsreformen, der trådte i kraft den 1. januar 2007, ændredes retskredsenes numre. Retskredsnummeret er det samme som myndighedskoden på www.tinglysning.dk. De nye retskredsnumre er følgende: Retskreds nr. 1 – Retten i Hjørring Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten i Aalborg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Randers Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Aarhus Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Viborg Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Holstebro Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Herning Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Horsens Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Kolding Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Esbjerg Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Sønderborg Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Odense Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Svendborg Retskreds nr. 14 – Retten i Nykøbing Falster Retskreds nr. 15 – Retten i Næstved Retskreds nr. 16 – Retten i Holbæk Retskreds nr. 17 – Retten i Roskilde Retskreds nr. 18 – Retten i Hillerød Retskreds nr. 19 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. 20 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 21 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 22 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 23 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 24 – Retten på Bornholm Indtil 1. januar 2007 havde retskredsene følende numre: Retskreds nr. 1 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Gentofte Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Gladsaxe Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Ballerup Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Hvidovre Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Rødovre Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Brøndbyerne Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Taastrup Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Tårnby Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. -

Referral of Paediatric Patients Follows Geographic Borders of Administrative Units

Dan Med Bul ϧϪ/Ϩ June ϤϢϣϣ DANISH MEDICAL BULLETIN ϣ Referral of paediatric patients follows geographic borders of administrative units Poul-Erik Kofoed1, Erik Riiskjær2 & Jette Ammentorp3 ABSTRACT e ffect of economic incentives rooted in local govern- ORIGINAL ARTICLE INTRODUCTION: This observational study examines changes ment’s interest in maximizing the number of patients 1) Department in paediatric hospital-seeking behaviour at Kolding Hospital from their own county/region who are treated at the of Paediatrics, in The Region of Southern Denmark (RSD) following a major county/region’s hospitals in order not to have to pay the Kolding Hospital, change in administrative units in Denmark on 1 January higher price at hospitals in other regions or in the pri- 2) School of 2007. vate sector. Treatment at another administrative unit is Economics and MATERIAL AND METHODS: Data on the paediatric admis- Management, usually settled with 100% of the diagnosis-related group University of sions from 2004 to 2009 reported by department of paedi- (DRG) value, which is not the case for treatment per - Aarhus, and atrics and municipalities were drawn from the Danish formed at hospitals within the same administrative unit. 3) Health Services National Hospital Registration. Patient hospital-seeking On 1 January 2007, the 13 Danish counties were Research Unit, behaviour was related to changes in the political/admini s- merged into five regions. The public hospitals hereby Kolding Hospital/ trative units. Changes in number of admissions were com- Institute of Regional became organized in bigger administrative units, each pared with distances to the corresponding departments. Health Services with more hospitals than in the previous counties [7]. -

Poisson Regression

EPI 204 Quantitative Epidemiology III Statistical Models April 22, 2021 EPI 204 Quantitative Epidemiology III 1 Poisson Distributions The Poisson distribution can be used to model unbounded count data, 0, 1, 2, 3, … An example would be the number of cases of sepsis in each hospital in a city in a given month. The Poisson distribution has a single parameter λ, which is the mean of the distribution and also the variance. The standard deviation is λ April 22, 2021 EPI 204 Quantitative Epidemiology III 2 Poisson Regression If the mean λ of the Poisson distribution depends on variables x1, x2, …, xp then we can use a generalized linear model with Poisson distribution and log link. We have that log(λ) is a linear function of x1, x2, …, xp. This works pretty much like logistic regression, and is used for data in which the count has no specific upper limit (number of cases of lung cancer at a hospital) whereas logistic regression would be used when the count is the number out of a total (number of emergency room admissions positive for C. dificile out of the known total of admissions). April 22, 2021 EPI 204 Quantitative Epidemiology III 3 The probability mass function of the Poisson distribution is λ ye−λ f (;y λ)= y! so the log-likelihood is for a single response y is L(λ | yy )= ln( λλ ) −− ln( y !) L '(λλ |yy )= / − 1 and the MLE of λλ is ˆ = y In the saturated model, for each observation y, the maximized likelihood is yyyln( )−− ln( y !) so the deviance when λ is estimated by ληˆ = exp( ) is 2(yyyy ln( )−− ln(λλˆˆ ) + ) = 2( yy ln( / λ ˆ ) − ( y − λ ˆ )) The latter term disappears when added over all data points if there is an intercept so ˆ D= 2∑ yyii ln( /λ ) Each deviance term is 0 with perfect prediction. -

Running Waters

Water flow at all scales Sand-Jensen, K. Published in: Running Waters Publication date: 2006 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Sand-Jensen, K. (2006). Water flow at all scales. In K. Sand-Jensen, N. Friberg, & J. Murphy (Eds.), Running Waters: Historical development and restoration of lowland Danish streams (pp. 55-66). Aarhus Universitetsforlag. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Running Waters EDITORS Kaj Sand-Jensen Nikolai Friberg John Murphy Biographies for Running Waters Kaj Sand-Jensen (born 1950) is professor in stream ecology at the University of Copenhagen and former professor in plant ecology and physiology at the University of Århus. He studies resource acquisition, photosynthesis, growth and grazing losses of phytoplankton, benthic algae and rooted plants in streams, lakes and coastal waters and the role of phototrophs in ecosystem processes. Also, he works with specifi c physiological processes, species adaptations and broad-scale patterns of biodiversity and metabolism in different aquatic ecosystems. Nikolai Friberg (born 1963) is senior scientist in stream ecology at the National Environmental Research Institute, Department of Freshwater Ecology in Silkeborg. He has a PhD from University of Copenhagen on the biological structure of forest streams and the effects of afforestation. His main focus is on macroinverte- brates: their interactions with other biological groups, impor- tance of habitat attributes and impacts of various human pressures such as hydromorphological alterations, pesticides and climate change. Also, he is involved in the assessment of stream quality using biological indicators and the national Danish monitoring programme. John Murphy (born 1972) is research scientist at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, River Communities Group in the United Kingdom. -

Regulativ for Gudenåen Silkeborg - Randers 2000 Regulativ for Gudenåen Silkeborg - Randers 2000

Regulativ for Gudenåen Silkeborg - Randers 2000 Regulativ for Gudenåen Silkeborg - Randers 2000 Viborg Amtsvandløb nr.: O 10 km 20 105 i Viborg amt 78 i Århus amt Indholdsfortegnelse side Forord 4 1. Grundlag for regulativet 5 2. Vandløbet 6 2. l Beliggenhed 6 2.2 Opmåling 6 2.3 Afmærkning 7 3. Vandløbets strækninger, vandføringsevne og dimensioner 9 3.1 Strækningsoversigt 9 3.2 Vandføringsevne 9 3.3 Dimensioner 10 4. Bygværker og tilløb. 12 4.1 Broer 12 4.2 Opstemningsanlæg 13 4.3 Andre bygværker 14 4.4 Større åbne tilløb 15 5. Administrative bestemmelser 16 5.1 Administration 16 5.2 Bygværker 16 5.3 Trækstien 17 6. Bestemmelser for sejlads 18 6.1 Generelt 18 6.2. Ikke - erhvervsmæssig sejlads 18 6.2. l Ikke - erhvervsmæssig sejlads på Tange Sø 18 6.3 Erhvervsmæssig sejlads 18 7. Bredejerforhold 19 7.1 Banketter 19 7.2 Arbejdsbælte langs vandløbet 19 7.3 Hegning 19 7.4 Ændring af vandløbets tilstand 19 7.5 Reguleringer m.m. 19 7.6 Forureninger m.v. 19 7.7 Drænudløb og grøfter 20 7.8 Skade på bygværker 20 7.9 Vandindvinding m.m. 20 7.10 Overtrædelse af bestemmelserne 20 8.1.1 Særbidrag 21 8.2 Oprensning 21 8.3 Grødeskæring 22 8.4 Kantskæring 22 8.5 Oprenset bundmateriale 22 9. Tilsyn 23 10. Revision 23 11. Regulativets ikrafttræden 23 Forord Dette regulativ er retsgrundlaget for administrationen af amtsvandløbet Gudenåen på strækningen mellem Silkeborg og Randers. Det indeholder bestemmelser om vandløbets fysiske udseende, vedligeholdelse samt de respektive amtsråds og lodsejeres forpligtelser og rettigheder ved vandløbet, og er derfor af stor betydning for såvel de afoandingsmæssige forhold som miljøet i og ved vandløbet. -

(Netherlands) (.Institute for Biological Archaeology

Acta Botanica Neerlandica 8 (1959) 156-185 Studies on the Post-Boreal Vegetational History of South-Eastern Drenthe (Netherlands) W. van Zeist (.Institute for Biological Archaeology , Groningen ) (received February 6th, 1959) Introduction In this paper the results of some palynological investigations of peat deposits in south-eastern Drenthe will be discussed. The location of the be discussed is indicated the of 1. This profiles to on map Fig. which is modified of the map, a slightly copy Geological Map (No. 17, sheets 2 and No. 2 and of the soils in the 4, 18, 4), gives a survey Emmen district. Peat formation took place chiefly in the Hunze Urstromtal, which to the west is bordered by the Hondsrug, a chain of low hills. It may be noted that the greater part of the raised bog has now vanished on account of peat cutting. In the eastern part of the Hondsrug fairly fertile boulder clay reaches the surface, whereas more to the in west general the boulder clay is covered by a more or less thick deposit of cover sand. Fluvio-glacial deposits are exposed on the eastern slope of the Hondsrug. Unfortunately, no natural forest has been left in south-eastern the in Drenthe. Under present conditions climax vegetation areas the with boulder clay on or slightly below surface would be a Querceto- Carpinetum subatlanticum which is rich in Fagus, that in the cover sand the boulder areas—dependent on the depth of clay—a Querceto roboris-Betuletum or a Fageto-Quercetum petraeae ( cf Tuxen, 1955). In contrast to the diagrams from Emmen and Zwartemeer previous- ly published (Van Zeist, 1955a, 1955b, 1956b) which provide a survey of the vegetational history of the whole Emmen district, the diagrams from Bargeroosterveld and Nicuw-Dordrecht have a more local character. -

Juleture 2020 Fyn - Sjælland Afg Mod Sjælland Ca

Juleture 2020 Fyn - Sjælland Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ København Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Roskilde Hillerød Helsingør Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Næstved Vordingborg Nykøbing F Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Korsør Slagelse Sorø Ringsted Køge Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Jylland - Fyn Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Aalborg Hobro Randers ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 200 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Aarhus ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Viborg Silkeborg ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Holstebro Herning ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Esbjerg Kolding Fredericia ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Skanderborg Horsens Vejle ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Sønderborg Aabenraa Haderslev ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Jylland - Sjælland Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Aalborg Hobro Randers ↔ København Afg mod Jylland ca. -

Exploring the Potential of the Strontium Isotope Tracing System in Denmark

Danish Journal of Archaeology, 2012 Vol. 1, No. 2, 113–122, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21662282.2012.760889 Exploring the potential of the strontium isotope tracing system in Denmark Karin Margarita Frei* Danish Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, CTR, SAXO Institute, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen, Denmark (Received 1 October 2012; final version received 14 November 2012) Migration and trade are issues important to the understanding of ancient cultures. There are many ways in which these topics can be investigated. This article provides an overview of a method based on an archaeological scientific methodology developed to address human and animal mobility in prehistory, the so-called strontium isotope tracing system. Recently, new research has enabled this methodology to be further developed so as to be able to apply it to archaeological textile remains and thus to address issues of textile trade. In the following section, a brief introduction to strontium isotopes in archaeology is presented followed by a state-of-the- art summary of the construction of a baseline to characterize Denmark’s bioavailable strontium isotope range. The creation of such baselines is a prerequisite to the application of the strontium isotope system for provenance studies, as they define the local range and thus provide the necessary background to potentially identify individuals originating from elsewhere. Moreover, a brief introduction to this novel methodology for ancient textiles will follow along with a few case studies exemplifying how this methodology can provide evidence of trade. The strontium isotopic system the strontium isotopic signatures are not changed in – from – Strontium is a member of the alkaline earth metal of a geological perspective very small time spans, due to Group IIA in the periodic table. -

The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Memory," Spectrum: Vol

Recommended Citation Price, Jillian (2012) "Accessing the Past as Landscape: The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Memory," Spectrum: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholars.unh.edu/spectrum/vol2/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals and Publications at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spectrum by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spectrum Volume 2 Issue 1 Fall 2012 Article 2 9-1-2012 Accessing the Past as Landscape: The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Memory Jillian Price University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/spectrum Price: Accessing the Past as Landscape: The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Accessing the Past as Landscape: The Danish Bog Bodies and Modern Memory By Jillian Price The idea of “place-making” in anthropology has been extensively applied to culturally created landscapes. Landscape archaeologists view establishing ritual spaces, building monuments, establishing ritual spaces, organizing settlements and cities, and navigating geographic space as activities that create meaningful cultural landscapes. A landscape, after all, is “an entity that exists by virtue of its being perceived, experienced, and contextualized by people” (Knapp and Ashmore 1999: 1). A place - physical or imaginary - must be seen or imagined before becoming culturally relevant. It must then be explained, and transformed (physically or ideologically). Once these requirements are fulfilled, a place becomes a locus of cultural significance; ideals, morals, traditions, and identity, are all embodied in the space. -

The Grauballe Man Les Corps Des Tourbières : L’Homme De Grauballe

Technè La science au service de l’histoire de l’art et de la préservation des biens culturels 44 | 2016 Archives de l’humanité : les restes humains patrimonialisés Bog bodies: the Grauballe Man Les corps des tourbières : l’homme de Grauballe Pauline Asingh and Niels Lynnerup Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/techne/1134 DOI: 10.4000/techne.1134 ISSN: 2534-5168 Publisher C2RMF Printed version Date of publication: 1 November 2016 Number of pages: 84-89 ISBN: 978-2-7118-6339-6 ISSN: 1254-7867 Electronic reference Pauline Asingh and Niels Lynnerup, « Bog bodies: the Grauballe Man », Technè [Online], 44 | 2016, Online since 19 December 2019, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/techne/1134 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/techne.1134 La revue Technè. La science au service de l’histoire de l’art et de la préservation des biens culturels est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Archives de l’humanité – Les restes humains patrimonialisés TECHNÈ n° 44, 2016 Fig. 1. Exhibition: Grauballe Man on display at Moesgaard Museum. © Medie dep. Moesgaard/S. Christensen. Techne_44-3-2.indd 84 07/12/2016 09:32 TECHNÈ n° 44, 2016 Archives de l’humanité – Les restes humains patrimonialisés Pauline Asingh Bog bodies : the Grauballe Man Niels Lynnerup Les corps des tourbières : l’homme de Grauballe Abstract. The discovery of the well-preserved bog body: “Grauballe Résumé. La découverte de l’homme de Grauballe, un corps Man” was a worldwide sensation when excavated in 1952.