Organized Crime Control Stenographic Report of H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Safety Committee

PUBLIC SAFETY COMMITTEE OF THE SUFFOLK COUNTY LEGISLATURE A regular meeting of the Public Safety Committee of the Suffolk County Legislature was held in the Rose Y. Caracappa Legislative Auditorium of the William H. Rogers Legislature Building, 725 Veterans Memorial Highway, Smithtown, New York on Thursday, May 31, 2012 at 9:30 a.m. MEMBERS PRESENT: Legislator Kate Browning, Chairperson Legislator Kara Hahn Legislator John Kennedy Legislator DuWayne Gregory Legislator Lou D'Amaro Legislator William Spencer MEMBERS NOT PRESENT: Legislator Robert Calarco, Vice-Chair ALSO IN ATTENDANCE: D.P.O. Wayne Horsley, Fourteenth Legislative District George Nolan, Counsel to the Legislature Barbara LoMoriello, Deputy Clerk, Suffolk County Legislature John Ortiz, Budget Review Office Terry Pearsall, Chief of Staff Josh Slaughter, Aide to Legislator Browning Bobby Knight, Aide to Presiding Officer Lindsay Michael Pitcher, Aide to Presiding Officer Lindsay Paul Perillie, Aide to Legislator Gregory Lora Gellerstein, Aide to Legislator Spencer Ali Nazir, Aide to Legislator Kennedy Justin little, Aide to Legislator D'Amaro Amy Keyes, Aide to Legislator Calarco Joe Williams, Commissioner, FRES Anthony LaFerrera, SC FRES Commission Jay Egan, Suffolk County FRES Commission Ed Webber, Acting Commissioner, Suffolk County Police Department James Burke, Chief of Department, Suffolk County Police Department Ted Nieves, Deputy Inspector, Suffolk County Police Department Tracy Pollack, Suffolk County Police Department Todd Guthy, Detective, Suffolk County Police Stuart -

Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor Annual Report

FINAL DRAFT WATERFRONT COMMISSION OF NEW YORK HARBOR ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 FINAL DRAFT To the Honorable Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor To the Honorable Phil Murphy, Governor and the Legislature of the State of New York and the Legislature of the State of New Jersey MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR “The outstanding investigative work by this Office’s prosecutors and our law enforcement partners uncovered a litany of crimes allegedly committed by members and associates of the Gambino organized crime family, who still don’t get it – handcuffs and a jail cell are waiting for criminals who threaten violence and commit fraud, money laundering and bribery in furtherance of their enterprise.” - United States Attorney for the Eastern District of New York Richard P. Donoghue, December 5, 2019 I am pleased to present to you the 2019-2020 Annual Report of the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor. To say that this was a tumultuous year is an understatement. We are still reeling from the ongoing onslaught of the COVID-19 Pandemic, which has ravaged our nation and the world, and changed life as we know it. We mourn the tragic loss of lives, and remember with sadness the passing of our friend and colleague, Linda Smith, who was a dedicated member of this agency for over 23 years. This year, we also witnessed one of the largest movements in this country’s history, with millions of people participating in mass demonstrations to protest systemic racism. While diversity and inclusion has long been an integral part of the Commission’s culture, we reaffirm our commitment to fairness and equality for all, regardless of race, color, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or religion. -

Download Pernamanzo.Indictment

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Hon. V. Crim. No. 20- JOHN PERNA and 18 U.S.C. §§ 1959(a)(3), (a)(6) THOMAS MANZO 18 u.s.c. § 1349 18 u.s.c. § 1519 18 u.s.c. § 2 INDICTMENT The Grand Jury in and for the District of New Jersey, sitting at Newark, charges: COUNT ONE (Violent Crime in Aid of Racketeering Activity Assault with a Dangerous Weapon) The Racketeering Enterprise At all times relevant to this Indictment: 1. Defendant JOHN PERNA was a member of a criminal organization referred to as the Lucchese Crime Family that operated in New Jersey, New York, and elsewhere. Accomplice- I was an associate of the Lucchese Crime Family. Defendant THOMAS MANZO was an associate of defendant JOHN PERNA. 2. The Lucchese Crime Family was part of a nationwide criminal organization known by various names, such as "the Mafia," "La Cosa Nostra," and "the MOB," which operated through entities known as "families." The Lucchese Crime Family, including its leadership, members, and associates, constituted an "enterprise," as defined in Title 18, United States Code, Section 1959(b)(2), that is, a group of individuals associated in fact that engaged in, and the activities of which affected interstate and foreign commerce. The Lucchese Crime Family (the "Enterprise") constituted an ongoing organization whose members functioned as a continuing unit for a common purpose of achieving the objectives of the Enterprise. 3. The Lucchese Crime Family operated through groups of individuals, headed by persons called "captains" or "capos," who control "crews" that consist of "made" members who, in tum, control subordinates, who are known as "associates" of the Enterprise. -

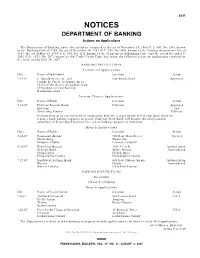

NOTICES DEPARTMENT of BANKING Actions on Applications

4211 NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF BANKING Actions on Applications The Department of Banking, under the authority contained in the act of November 30, 1965 (P. L. 847, No. 356), known as the Banking Code of 1965; the act of December 14, 1967 (P. L. 746, No. 345), known as the Savings Association Code of 1967; the act of May 15, 1933 (P. L. 565, No. 111), known as the Department of Banking Code; and the act of December 9, 2002 (P. L. 1572, No. 207), known as the Credit Union Code, has taken the following action on applications received for the week ending July 24, 2007. BANKING INSTITUTIONS Section 112 Applications Date Name of Individual Location Action 7-19-07 J. Donald Steele, Jr., and Northumberland Approved Joanne K. Steele, to acquire up to 35.0% of the shares of common stock of Northumberland Bancorp, Northumberland Interim Charter Applications Date Name of Bank Location Action 7-18-07 Elderton Interim Bank Elderton Approved Elderton and Armstrong County Effective Incorporation of an interim bank in conjunction with the reorganization of Elderton State Bank to create a bank holding company structure. Elderton State Bank will become the wholly-owned subsidiary of Keystrong Financial, Inc., a new holding company in formation. Branch Applications Date Name of Bank Location Action 5-14-07 CommunityBanks 749 East Main Street Opened Millersburg Mount Joy Dauphin County Lancaster County 6-25-07 Beneficial Mutual 1520 Cecil B. Authorization Savings Bank Moore Avenue Surrendered Philadelphia Philadelphia Philadelphia County Philadelphia County 7-12-07 Northwest Savings Bank 605 East Dubois Avenue Authorization Warren Dubois Surrendered Warren County Clearfield County SAVINGS INSTITUTIONS No activity. -

Is the Mafia Taking Over Cybercrime?*

Is the Mafia Taking Over Cybercrime?* Jonathan Lusthaus Director of the Human Cybercriminal Project Department of Sociology University of Oxford * This paper is adapted from Jonathan Lusthaus, Industry of Anonymity: Inside the Business of Cybercrime (Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2018). 1. Introduction Claims abound that the Mafia is not only getting involved in cybercrime, but taking a leading role in the enterprise. One can find such arguments regularly in media articles and on blogs, with a number of broad quotes on this subject, including that: the “Mafia, which has been using the internet as a communication vehicle for some time, is using it increasingly as a resource for carrying out mass identity theft and financial fraud”.1 Others prescribe a central role to the Russian mafia in particular: “The Russian Mafia are the most prolific cybercriminals in the world”.2 Discussions and interviews with members of the information security industry suggest such views are commonly held. But strong empirical evidence is rarely provided on these points. Unfortunately, the issue is not dealt with in a much better fashion by the academic literature with a distinct lack of data.3 In some sense, the view that mafias and organised crime groups (OCGs) play an important role in cybercrime has become a relatively mainstream position. But what evidence actually exists to support such claims? Drawing on a broader 7-year study into the organisation of cybercrime, this paper evaluates whether the Mafia is in fact taking over cybercrime, or whether the structure of the cybercriminal underground is something new. It brings serious empirical rigor to a question where such evidence is often lacking. -

Women's Crime and Criminal Administration in Pennsylvania, 1763-1790

Women's Crime and Criminal Administration in Pennsylvania, 1763-1790 NN WINTER appeared in court first in the December, 1764, term of Philadelphia County's court of quarter sessions charged Awith felonious theft; she suffered corporal punishment when a jury found against her. In 1770 and again in 1773, she appeared before Lancaster County's general sessions, in the first instance having a count of assault against her dismissed, in the second being convicted of stealing. Back in Philadelphia in September, 1777, she pleaded guilty to a third charge of theft and was sentenced to jail. In April 1779, before the mayor's court in Philadelphia and this time using the alias Mary Flood, Ann Winter was convicted of three counts of larceny and received thirty-nine lashes on her bare back for each conviction. She was by this time known as "a Notorious Thief." Records reveal she was also in "a forlorn condition," the mother of "two fatherless children," and again "big with child." Should she be released and her fine remitted, she promised authorities in November, 1779, they "should never after this time hear of the least blemish against her character As she intended retiring into the country to endeavour for an honest livelihood." Promises aside, Winter was again convicted of larceny in March, 1780, this time in oyer and terminer proceedings, and once more suffered corporal punishment and confinement. She was also judged guilty of larceny in the mayor's court in July, 1782, and in July, 1785, and pleaded guilty to still another charge of theft in April, 1784. -

Gotham Unbound: How New York City Was Liberated from the Grip of Organized Crime

BOOK REVIEW REGIONAL LABOR REVIEW Fall 2000 Gotham Unbound: How New York City Was Liberated From the Grip of Organized Crime James B. Jacobs, with Coleen Friel and Robert Radick. New York: New York University Press, 1999. reviewed by Louis J. Kern While James B..Jacobs does not maintain that the Mafia was the only organized crime group in twentieth-century America, it is his central contention that the Italian-American controlled organized crime families that since the 1930s have dominated illicit businesses—loan-sharking, protection rackets, drugs, prostitution and pornography—also have played a significant and largely unique role in infiltrating and corrupting legitimate businesses and labor unions in larger urban centers like the New York metropolitan area. The Cosa Nostra, he believes, due to its aggressive and often violent racketeering, achieved, in the period between 1920 and 1990 a preeminent criminal economic power that carried with it exceptional social status and significant political influence. By the 1980s Mafia business interests were divided among five organized-crime families—the Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese, Bonanno, and Colombo. Though the New York City mob has penetrated dozens of city industries since 1920, Jacobs focuses on six key industries that have been extensively and continuously dominated by organized crime. The “mobbed-up” industries that provide the focus for his study are: the garment industry, air freight transport and storage at John F. Kennedy International Airport, Construction and exhibition trades at the Jacob Javits Convention Center, parking and loading/unloading at Fulton Fish Market, the solid waste hauling business in the five boroughs and on Long Island, and the construction industry. -

La Cosa Nostra in the US

NIJ - International Center - U.N Activities - La Cosa Nostra in the US Participating in the U.N.'s crime prevention program. LA COSA NOSTRA IN THE UNITED STATES by James O. Finckenauer, Ph.D. International Center National Institute of Justice Organizational Structure La Cosa Nostra or LCN -- also known as the Mafia, the mob, the outfit, the office -- is a collection of Italian- American organized crime “families” that has been operating in the United States since the 1920s. For nearly three quarters of a century, beginning during the time of Prohibition and extending into the 1990s, the LCN was clearly the most prominent criminal organization in the U.S. Indeed, it was synonymous with organized crime. In recent years, the LCN has been severely crippled by law enforcement, and over the past decade has been challenged in a number of its criminal markets by other organized crime groups. Nevertheless, with respect to those criteria that best define the harm capacity of criminal organizations, it is still pre-eminent. The LCN has greater capacity to gain monopoly control over criminal markets, to use or threaten violence to maintain that control, and to corrupt law enforcement and the political system than does any of its competitors. As one eminent scholar has also pointed out, “no other criminal organization [in the United States] has controlled labor unions, organized employer cartels, operated as a rationalizing force in major industries, and functioned as a bridge between the upperworld and the underworld” (Jacobs, 1999:128). It is this capacity that distinguishes the LCN from all other criminal organizations in the U.S. -

Epilogue on the Lack of African-American (And Other)

EPILOGUE ON THE LACK OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN (AND OTHER) ORGANIZED CRIME RESEARCH THE RELATIVE DEARTH OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN ORGANIZED CRIME RESEARCH I began this research in 1992 when a colleague asked me if I could investigate the activities and networks of an African-American gangster named Jack Brown.1 My associate was particularly interested in Brown’s operations in the Philadelphia region in the 1970s. Local and federal law enforcement officials in the area did not have – or at least did not offer – much information on Jack Brown, though they did maintain extensive files on a relatively large and significant organized crime group named the “Black Mafia”. When I was first introduced to the topic, and more importantly shown the voluminous files within several agencies, my reaction was one of amazement. The files were substantial. Many of the group’s activities, as has been demonstrated in the pages above, were notorious – the DuBrow Furniture robbery/arson/murder, the Hanafi murders, the misappropriation of community “seed” money, the murder of Major Coxson, and the complex role of Philadelphia’s Black Muslim Mosque #12 – including the relationships of boxing legend Muhammad Ali to Major Coxson and to Jeremiah Shabazz. In addition to other noteworthy aspects of the group, there were the astronomical number of internecine murders, and the facts that two of the Black Mafia founding members spent time on the FBI’s Most Wanted list (which has only listed 458 people since its inception), and that for a time the group accounted for 80% of the city’s heroin market. Then there were the significant activities of Black Mafia members as they rotated in and out of the prison system over the course of approximately 25 years. -

Download Download

1 Guilt for the Guiltless: The Story of Steven Crea, the Murder of Michael Meldish and Other Tales by Lisa Babick – aka “MS” “….the other thing we’ve learned…is just how large the uni- verse of other people who wanted the guy dead is.” Judge Cathy Siebel on Michael Meldish during a bail hearing for Steven D. Crea on August 3, 2018 2 On November 15, 2013, on a quiet street in the Throggs Neck neighborhood of the Bronx, 62-year-old Michael Meldish was found dead in his car with a single, fatal gunshot wound to the right side of his head. Police were more than giddy about the murder, immediately telling news outlets they believed it was a “gangland-style” execution. Meldish was one of the reputed leaders of the Purple Gang – a criminal group that controlled the drug trade in the Bronx and Harlem in the 70s and 80s. They were said to have killed and dismembered over 100 rivals, with Meldish having committed at least half of those murders himself. Police described him as a “stone-cold killer.” Law enforcement pursued Meldish for more than 30 years but was wildly unsuccessful in bringing any charges against him even though he had been arrested 18 times since the early 70s. Joseph Coey, former head of the NYPD Organized Crime Homicide Task Force, blamed it on witnesses who wouldn’t come forward. “They had the people so terrified they just wouldn’t cooperate,” he said. He then added that Meldish’s murder “should have happened a long time ago. -

The Pennsylvania Juvenile Justice Task Force

THE PENNSYLVANIA JUVENILE JUSTICE TASK FORCE REPORT & RECOMMENDATIONS June 2021 Table of Contents Members of the Pennsylvania Juvenile Justice Task Force ............................................ 3 Executive Summary of Findings .................................................................................... 4 Overview of Task Force Recommendations................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 Key Findings ............................................................................................................... 12 Policy Recommendations ............................................................................................ 30 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 43 Appendices ................................................................................................................. 44 Appendix I: Glossary of Terms ................................................................................. 45 Appendix II: County Data Maps ............................................................................... 46 Appendix III: Financial Obligations by County ......................................................... 50 Appendix IV: Data Sources and Methods ................................................................ 56 Appendix V: System Flowchart ............................................................................... -

Crime, Justice, and Order in the North Carolina Piedmont, 1760-1806

STROUD, JASON MICHAEL, Ph.D. Crime, Justice, and Order in the North Carolina Piedmont, 1760-1806. (2019) Directed by Dr. Greg O’Brien. 345 pp. This dissertation examines crime and disorder in the North Carolina Piedmont between 1760 and 1806, exploring the ways that criminal justice and the law were enforced in the region. It is rooted in an analysis of the colonial and state Superior Court records from Salisbury and Hillsborough and traces the process by which authorities— first the colonial government and then the revolutionary state—attempted to establish and maintain order in the region. This most basic function of criminal justice necessarily involved the identification of individuals and groups of people as criminals by the state. I argue that understanding this legal and juridical process, which marked many of the people of the region as unfit subjects and citizens, helps provide a framework for understanding the turmoil and disorder that characterized the Revolutionary era in the region. As the North Carolina government sought to assert its legitimacy through imposing order, it marked presumptively disorderly men and women including horse thieves, land squatters, “Regulators,” Loyalists, and, significantly, the enslaved, as outlaws. Faced with alienation from legal and political legitimacy, these people resisted, articulating in the process a different conception of justice, one rooted in the social, political, and cultural realities of the region. This dissertation, then, traces a pattern of conflict and turmoil that reveals very different, and at times diametrically opposed, understandings of justice between governing elites and local men and women in the Piedmont. Moreover, by focusing on the interrelated issues of criminality, justice, and order, this work attempts to deepen scholarly understanding of the Revolution in the North Carolina backcountry, in particular the ways it affected the relationship between individuals and the state.