9772863 Brad Hosking Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide Represents the Most Requested Songs at Weddings and Parties

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide represents the most requested songs at Weddings and Parties. Please circle songs you like and cross out the ones you don’t. You can also write-in additional requests on the back page! WEDDING SONGS ALL TIME PARTY FAVORITES CEREMONY MUSIC CELEBRATION THE TWIST HERE COMES THE BRIDE WE’RE HAVIN’ A PARTY SHOUT GOOD FEELIN’ HOLIDAY THE WEDDING MARCH IN THE MOOD YMCA FATHER OF THE BRIDE OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL BACK IN TIME INTRODUCTION MUSIC IT TAKES TWO STAYIN ALIVE ST. ELMOS FIRE, A NIGHT TO REMEMBER, RUNAROUND SUE MEN IN BLACK WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU RAPPERS DELIGHT GET READY FOR THIS, HERE COMES THE BRIDE BROWN EYED GIRL MAMBO #5 (DISCO VERSION), ROCKY THEME, LOVE & GETTIN’ JIGGY WITH IT LIVIN, LA VIDA LOCA MARRIAGE, JEFFERSONS THEME, BANG BANG EVERYBODY DANCE NOW WE LIKE TO PARTY OH WHAT A NIGHT HOT IN HERE BRIDE WITH FATHER DADDY’S LITTLE GIRL, I LOVED HER FIRST, DADDY’S HANDS, FATHER’S EYES, BUTTERFLY GROUP DANCES KISSES, HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY, HERO, I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, IF I COULD WRITE A SONG, CHICKEN DANCE ALLEY CAT CONGA LINE ELECTRIC SLIDE MORE, ONE IN A MILLION, THROUGH THE HANDS UP HOKEY POKEY YEARS, TIME IN A BOTTLE, UNFORGETTABLE, NEW YORK NEW YORK WALTZ WIND BENEATH MY WINGS, YOU LIGHT UP MY TANGO YMCA LIFE, YOU’RE THE INSPIRATION LINDY MAMBO #5BAD GROOM WITH MOTHER CUPID SHUFFLE STROLL YOU RAISE ME UP, TIMES OF MY LIFE, SPECIAL DOLLAR WINE DANCE MACERENA ANGEL, HOLDING BACK THE YEARS, YOU AND CHA CHA SLIDE COTTON EYED JOE ME AGAINST THE WORLD, CLOSE TO YOU, MR. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop by by Stone Temple Pilots

Read and Download Ebook [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs From The Vatican Gift Shop PDF [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop PDF [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop by by Stone Temple Pilots PDF File: [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs From The Vatican Gift Shop 1 Read and Download Ebook [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs From The Vatican Gift Shop PDF [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop PDF [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop by by Stone Temple Pilots Tiny Music... Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop is the third album by American rock band Stone Temple Pilots, released on March 26, 1996 on Atlantic Records. After a brief hiatus in 1995, STP regrouped to record Tiny Music, living and recording the album together in a mansion in Santa Barbara, California.[3] The album had three singles reach #1 on the Mainstream Rock Tracks chart, including "Big Bang Baby", "Lady Picture Show", and "Trippin' on a Hole in a Paper Heart." ->>>Download: [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop PDF ->>>Read Online: [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop PDF PDF File: [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs From The Vatican Gift Shop 2 Read and Download Ebook [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs From The Vatican Gift Shop PDF [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop Review This [FREE] Tiny Music: Songs from the Vatican Gift Shop book is not really ordinary book, you have it then the world is in your hands. The benefit you get by reading this book is actually information inside this reserve incredible fresh, you will get information which is getting deeper an individual read a lot of information you will get. -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

2013 March 26 April 2

NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE STREET DATES: MARCH 26 APRIL 2 ORDERS DUE: FEB 27 ORDERS DUE: MARCH 6 ISSUE 7 wea.com 2013 3/26/13 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ORDERS ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP DUE A Rocket To The Moon Wild & Free FBY CD 075678766725 530448 $13.99 2/27/13 The Carol Burnett Show: This Time Burnett, Carol TSV DV 610583447392 27576-X $59.95 2/27/13 Together (6DVD) Original Album Series (5CD) - Has Chicago FLA CD 081227980139 524559 $21.95 2/27/13 been CANCELLED Original Album Series (5CD) - Cooper, Alice FLS CD 081227983574 522056 $21.95 2/27/13 BUMPED TO 4/23/13 Original Album Series (5CD) - Doobie Brothers, The FLS CD 081227975401 528898 $21.95 2/27/13 BUMPED TO 4/23/13 Doors, The Morrison Hotel FLE CD 603497924554 535080 $4.98 2/27/13 Original Album Series (5CD) - Franklin, Aretha FLE CD 081227982799 522563 $21.95 2/27/13 BUMPED TO 4/23/13 Kvelertak Meir RRR CD 016861761325 176132 $13.99 2/27/13 Manhattan Transfers, The Best Of The Manhattan Transfers FLE CD 081227966690 19319-F $4.98 2/27/13 The Marconi Marconi LAT CD 825646468805 535023 $11.98 2/27/13 530386- Shelton, Blake Based On A True Story… WNS CD 093624946113 $18.98 2/27/13 W Stills, Stephen Carry On (4CD) ACG CD 081227967864 534539 $54.98 2/27/13 Original Album Series (5CD) - Stone Temple Pilots FLE CD 081227971854 532180 $21.95 2/27/13 BUMPED TO 4/23/13 Wavves Afraid Of Heights WB CD 093624945369 534721 $13.99 2/27/13 Wavves Afraid Of Heights (Vinyl w/Bonus CD) WB A 093624945376 534721 $22.98 2/27/13 Last Update: 02/12/13 For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. -

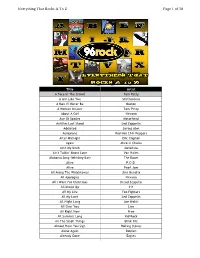

Of 30 Everything That Rocks a to Z

Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 1 of 30 Title Artist A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty A Girl Like You Smithereens A Man I'll Never Be Boston A Woman In Love Tom Petty About A Girl Nirvana Ace Of Spades Motorhead Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Addicted Saving Abel Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers After Midnight Eric Clapton Again Alice In Chains Ain't My Bitch Metallica Ain't Talkin' About Love Van Halen Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar) The Doors Alive P.O.D. Alive Pearl Jam All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All Apologies Nirvana All I Want For Christmas Dread Zeppelin All Mixed Up 311 All My Life Foo Fighters All My Love Led Zeppelin All Night Long Joe Walsh All Over You Live All Right Now Free All Summer Long Kid Rock All The Small Things Blink 182 Almost Hear You Sigh Rolling Stones Alone Again Dokken Already Gone Eagles Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 2 of 30 Always Saliva American Bad Ass Kid Rock American Girl Tom Petty American Idiot Green Day American Woman Lenny Kravitz Amsterdam Van Halen And Fools Shine On Brother Cane And Justice For All Metallica And The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen Angel Aerosmith Angel Of Harlem U2 Angie Rolling Stones Angry Chair Alice In Chains Animal Def Leppard Animal Pearl Jam Animal I Have Become Three Days Grace Animals Nickelback Another Brick In The Wall Pt. 2 Pink Floyd Another One Bites The Dust Queen Another Tricky Day The Who Anything Goes AC/DC Aqualung Jethro Tull Are You Experienced? Jimi Hendrix Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Armageddon It Def Leppard Around -

December 1996

While lead singer Scott Wieland gets his act together off the bandstand, Stone Temple Pilots' latest, Tiny Music, hits the charts without a touring band to sup- port it. Drummer Eric Kretz isn't one to twiddle his thumbs, though, and an STP side project might end up being the new canvas for his powerful and tasty playing, by Matt Peiken 44 Toto, I don't think we're in the Opry anymore, These days Garth Brooks' drummer is slamming under an acrylic "pod" to fifty thousand screaming fans a night, Mike Palmer tells tales of high-tech honky tonkin' on the new by Robyn Flans 64 Soundgarden's Matt Cameron and the Foo Fighters' Will Goldsmith have been appearing all A staunch refusal to conform may have kept over MTV behind a strange new drumkit with Fishbone off the charts for years, but it's also provid- wooden hoops. It's no surprise people have ed tons of crazy, cookin', funky, freaky music for fans been asking lots of questions about the drums' who know where to look and listen. Now a new origin. Answer: Vancouver, where custom Ayotte album and lineup have reenergized drummer Philip kits have been pumped out—one at a time—for "Fish" Fisher, who's still adding his ever-powerful and longer than you might think. creative percussives to the Fishy stew. by Rick Van Horn by Matt Peiken 80 98 photo by John Eder Volume 2O, Number 12 Cover photo by John Eder education equipment 112 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC 24 NEW AND NOTABLE A Different Slant For The Hi-Hat, Part 1 New From Nashville NAMM by Rod Morgenstein 32 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP 114 ROCK PERSPECTIVES Fibes -

The Ithacan, 2002-04-25

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 2001-02 The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 4-25-2002 The thI acan, 2002-04-25 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2001-02 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 2002-04-25" (2002). The Ithacan, 2001-02. 28. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2001-02/28 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 2001-02 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. I I I' I 1., j I , 'I VOL. 69, No. 27 THURSDAY ITHACA, N.Y. APRIL 25, 2002 28 PAGES, FREE www.ithaca.edu/ithacan The Newspaper for the Ithaca College Community Local rate Nader calls for action for phones BY ANNE K. WALTERS "Corporations should get out Staff Writer of politics," Nader said. 'They're not voters, they're not to increase Former Green Party presi real human beings, they're artifi dential candidate Ralph Nader is cial entities." BY EMILY PAULSEN sued a cry against corporate Nader also said the definition Staff Writer waste and called students to be of pollution needs to change to come civic activists during an a form of deadly violence. Most students living on campus will Earth Day speech at Ithaca Col Then people will begin to look pay more for local telephone service be lege Monday night. at what they can do to effect ginning in the fall 2002 semester. -

2 Column Indented

22,000 Karaoke Songs - AMS Entertainment ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years Duck And Run 6188 Through The Iris 20005 Here By Me 17629 Wasteland 16042 Here Without You 13010 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 10,000 Maniacs Kryptonite 6190 Because The Night 1750 Landing In London 17631 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Let Me Be Myself 25227 Like The Weather 16149 Let Me Go 13785 More Than This 16150 Live For Today 13648 These Are The Days 1273 Loser 6192 Trouble Me 16151 Road I'm On, The 6193 So I Need You 17632 10cc When I'm Gone 13086 Donna 20006 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 30 Seconds To Mars I'm Mandy 16152 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 I'm Not In Love 2631 Rubber Bullets 20007 311 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 All Mixed Up 16156 Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Don't Tread On Me 13649 First Straw 22322 112 Love Song 22323 Come See Me 25019 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Dance With Me 22319 It's Over Now 22320 38 Special Peaches & Cream 22321 Caught Up In You 1904 U Already Know 13602 Hold On Loosely 1901 Second Chance 17633 2 Tons O' Fun Teacher, Teacher 13492 It's Raining Men (Hallelujah!) 6017 3LW 2 Unlimited No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 11795 No Limits 6183 3Oh!3 20 Fingers Don't Trust Me 16157 Short Dick Man 1962 3OH!3 & Katy Perry 2Pac Starstrukk 25138 California Love (Original Version) 14147 Changes 12761 4 Him Ghetto Gospel 16153 Basics Of Life 20002 For Future Generations 20003 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Thesis Corrected Vol2.Pdf (1.596Mb)

Multimedia and Live Performance Ian Willcock Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of PhD Institute of Creative Technologies De Montfort University December 2011 Volume Two Bibliography Agile Alliance, (2001). Agile Alliance: The Agile Manifesto. [Web page] Available at: http://www.agilealliance.org/the-alliance/the-agile-manifesto/ (Accessed June 9, 2011). Allison, J. T. & Place, T. A. (2005) Teabox: A Sensor Data Interface System. Proceedings of the 2005 Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME-05). Vancouver, Canada,pp56-59. Anderson, D. P. &Kuivila, R. (1990) A system for computer music performance.ACM Trans. Comput. Syst., 8,pp56-82. Anderson, D. P. &Kuivila., R. (1991) Formula: A Programming Language for Expressive Computer Music. Computer, 24,pp12-21. Apache Subversion. (no date) [software] Available at: http://subversion.apache.org/ (Accessed June 17, 2011). Audacity (2010) [Software] (version 1.3) Available at http://audacity.sourceforge.net/about/?lang=en Auslander, P. (2009) Reactivation: Performance, Mediatization and the Present Moment. In Chatzichristodoulou, M., Jeffries, J. &Zerihan, R. (Eds.) Interfaces of Performance, pp 81-94.Farnham, Ashgate Publishing Ltd. Auvray, S., (2008).InfoQ: Distributed Version Control Systems: A Not-So-Quick Guide Through. Available at: http://www.infoq.com/articles/dvcs-guide (Accessed June 19, 2011) Aylward, R. &Paradiso, J. (2006) Sensemble: A Wireless, Compact, Multi-User Sensor System for Interactive Dance.Proceedings of the 2006 Conference onNew Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME-06). Paris, France,pp134-139. Barbosa, A. (2003) Displaced Soundscapes: A Survey of Network Systems for Music and Sonic Art Creation. Leonardo Music Journal, 13. Barbosa, A., Cardoso, J.