Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2016-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2008

Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2008 Virginia S. Gillerman E.H. Bennett Idaho Geological Survey Morrill Hall, Third Floor Staff Report 09-5 University of Idaho June 2009 Moscow, Idaho 83844-3014 Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2008 Virginia S. Gillerman E.H. Bennett Staff Reports present timely information for public distribution. This publication may not conform to the agency’s standards. Idaho Geological Survey Morrill Hall, Third Floor Staff Report 09-5 University of Idaho June 2009 Moscow, Idaho 83844-3014 Contents Metal Mining ......................................................... 1 Phosphate Industry ..................................................... 3 Other Industrial Minerals ................................................ 4 Energy ............................................................... 5 Exploration ........................................................... 5 State Activities ........................................................ 8 Illustrations Figure 1. Idaho non-fuel mineral production ................................. 9 Figure 2. Commodity breakdown of USGS mineral value data for Idaho ............................................. 10 Figure 3. Galena mine, Coeur d’Alene District, Idaho ......................... 11 Figure 4. Agrium’s D pit at Dry Valley phosphate mine, Caribou County, Idaho ........................................... 11 Figure 5. Idaho industrial minerals map for 2008, not including phosphate .......................................... 12 Figure 6. Idaho exploration map in 2008 .................................. -

Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2019

Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2019 Virginia S. Gillerman Idaho Geological Survey (Boise) www.idahogeology.org American Exploration and Mining Association Reno, NV December 4, 2019 Acknowledgements AEMA Idaho Dept. of Lands staff BLM and USFS minerals staff Industry geologists IGS and Claudio Berti (new IGS Director) Earl Bennett 2019 Trends and Highlights Phosphate Reigns in Idaho Lucky Friday strike? Gold Renaissance – North, South and in between! Cobalt/Critical Minerals Price Matters Social License and Public Perception Exciting Development Projects Idaho-based Companies 2018 Leading Commodities: Phosphate rock, Sand and Gravel, Crushed Stone, Pb and Ag Idaho Non-fuel Mineral Production Idaho Non-fuel Mineral Production (USGS data) 1,400,000 1,200,000 1,000,000 800,000 600,000 000sof $ 400,000 200,000 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018P Metals $ Total $ Dec. 2014: Thompson Creek Mo on care and maintenance; large March 2017: Lucky Friday resource remains. miners go on strike. Metal prices (5-years) Co Au Mo: $ 9.70/lb. (LME, Platt’s, 11/20/2019) vs. >$ 11 at end of 2018. Ag Two World Class Mining Districts Coeur d’Alene District: Over 1.24 billion troy ounces Ag (38,568 metric tons) Pb, Zn, Cu, Sb Quartz-Siderite-Sulfide veins in PC Belt metasedimentary rocks Deep mines, ore extends vertically SE Phosphate District: Also over 100 years production Permian Phosphoria Formation Sedimentary apatite-rich black shale of regional extent Coeur d’Alene district (Silver Valley) Murray 2019 Active: Lucky Friday Galena Complex (inc. Coeur) Inactive, but resource in ground: Sunshine Bunker Hill – Zn, renegotiated lease Hecla Mining Company: Lucky Friday mine 2018 Sentinels of Safety 2019 production by salaried employees up Award by NMA (115,682 oz. -

H:\IBLA Convert\Converted\184IBLA\WPD\L087-105.Wpd

UNITED STATES v. RESOURCE TECHNICS, LLC and STONE RESOURCES, LLC 184 IBLA 87 Decided July 31, 2013 United States Department of the Interior Office of Hearings and Appeals Interior Board of Land Appeals 801 N. Quincy St., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22203 UNITED STATES v. RESOURCE TECHNICS, LLC and STONE RESOURCES, LLC IBLA 2012-233 Decided July 31, 2013 Appeal from a decision of Administrative Law Judge Robert G. Holt dismissing a contest complaint challenging the validity of placer mining claims. Contest No. UTU-87817. Affirmed. 1. Mining Claims: Common Varieties of Minerals: Generally--Mining Claims: Determination of Validity The test for determining whether a deposit of building stone is an uncommon variety that is locatable under the mining laws requires a claimant to meet the five criteria codified at 43 C.F.R. § 3830(b): (1) there must be a comparison of the mineral deposit with other deposits of such mineral generally; (2) the mineral deposit at issue must have a unique property; (3) the unique property must give the deposit a distinct and special value; (4) if the special value is for uses to which ordinary varieties of the mineral are put, the deposit must have some distinct and special value for such use; and (5) the distinct and special value must be reflected by the higher price which the material commands in the market place. 2. Administrative Procedure: Burden of Proof--Evidence: Preponderance--Evidence: Prima Facie Case--Mining Claims: Contests In a contest, the Government bears the burden of going forward with evidence sufficient to establish a prima facie case of the invalidity of the challenged mining claim. -

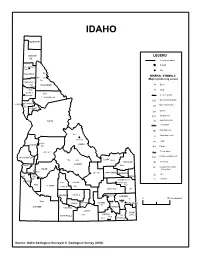

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY of IDAHO This Chapter Has Been Prepared Under a Memorandum of Understanding Between the U.S

IDAHO BOUNDARY BONNER LEGEND DS County boundary Capital Coeur d'Alene SG City Ag KOOTENAI MINERAL SYMBOLS Pb Zn roducing areas) Sb (Major p BENEWAH Gar SHOSHONE Ag Silver Gem Gem Au Gold LATAH Gem Moscow Cem Cement plant CLEARWATER D-Q Dimension quartzite NEZ PERCE Lewiston Dimension stone SG DS LEWIS Gar Garnet Gem Gemstones IDAHO IS Industrial sand Lime Lime plant Mo Molybdenum Au P Phosphate rock Salmon Pb Lead McCall ADAMS LEMHI SG Per Perlite VALLEY Per Perlite plant Pumice and pumicite WASHINGTON Pum Mo D-Q CLARK Gem FREMONT Sb Antimony CUSTER PAYETTE Gem SG Construction sand BOISE and gravel IS Gem BUTTE JEFFERSON MADISON Caldwell Zn Zinc SG D-Q Boise TETON Zeo Zeolites SG BONNEVILLE CANYON Pum BLAINE Idaho Falls ADA Pum ELMORE CAMAS SG BINGHAM DS LINCOLN GOODING Pocatello CARIBOU 0 100 Kilometers Lime P Cem Gem IS JEROME MINIDOKA POWER Soda Springs IS OWYHEE Twin Falls BANNOCK CASSIA BEAR D-Q ONEIDA Zeo LAKE TWIN FALLS Pum Per Per FRANKLIN Source: Idaho Geological Survey/U.S. Geological Survey (2002) THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF IDAHO This chapter has been prepared under a Memorandum of Understanding between the U.S. Geological Survey and the Idaho Geological Survey for collecting information on all nonfuel minerals. In 2002, the estimated value1 of nonfuel mineral production and a $4 million decrease in gold. Industrial sand and gravel, for Idaho was $301 million, based upon preliminary U.S. construction sand and gravel, and zinc were down $2 million Geological Survey (USGS) data. This was a 4.5% increase from or less each (descending order of change) (table 1). -

The Mineral Industry of Idaho

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF IDAHO This chapter has been prepared under a Memorandum of Understanding between the U.S. Geological Survey and the Idaho Geological Survey for collecting information on all nonfuel minerals. In 2000, the estimated value1 of nonfuel mineral production producer of construction and industrial sand and gravel and for Idaho was $399 million, based upon preliminary U.S. dimension stone. Geological Survey (USGS) data. This was a 1.7% decrease The Idaho Geological Survey3 (IGS) provided the narrative from that of 19992 and followed a 7.5% decrease from 1998 to information that follows. Production data in the following text 1999. The State remained 33d in rank among the 50 States in are those reported by the IGS, based upon its own survey and total nonfuel mineral production value, of which Idaho estimates. The data differ from some production figures accounted for 1% of the U.S. total. reported by the USGS. Low metal prices took their toll on Phosphate rock, silver, construction sand and gravel, Idaho’s mining industry in 2000, even as high demand for molybdenum, and lead were, by value, Idaho’s leading nonfuel industrial minerals and construction materials contributed to minerals. In 2000, molybdenum concentrates and construction increased exploration activity for several commodities. sand and gravel values (listed in descending order of change) According to statistics compiled by the Idaho Department of increased by about $5 million each and those of portland cement Labor, employment in metal mining declined during 2000 from and zinc, about $2 million each. Smaller increases also 1,300 in January to 1,200 persons in December 2000. -

Download FY 2020 Annual Report

On the Cover Top right: IGS geologist investigates tension cracks and sand boils associated with the collapse of the inlet delta at Stanley Lake. Bottom right: Idaho Transportation Department pilot prepares a state aircraft for departure from Upper Loon airstrip after deployment of a broadband seismometer from IGS and Boise State University personnel in response to the M6.5 Stanley earthquake of March 31st, 2020. Bottom left: IGS geologist retrieves seismic data from one of the temporary seismic stations at Thomas Creek airstrip deployed in response to the M6.5 Stanley earthquake of March 31st, 2020. Top left: Earthquakes during FY 2020 in Idaho and location of the temporary seismic monitoring network deployed by IGS and collaborating partners. Source: USGSANSS Comprehensive Earthquake Catalog for 07-01-2019 to 06-30-2020. Annual Report of the Idaho Geological Survey Fiscal Year 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 1 Mission . .1 Vision . .1 From the Director . .2 Organization and Personnel . .3 Organization Chart . 3 Directory . 4 Idaho Geological Survey Advisory Board. .5 Idaho Geological Mapping Advisory Committee . 6 Fiscal Overview . 7 Partnerships . .9 Funding Partners . .9 Collaborators . .10 Research . 11 Geological Mapping and Related Studies . 11 Hydrogeology . .13 Geologic Hazards. .16 Mineral Resources and Mining . 19 Energy . 26 Outreach . 31 Publications. .31 Website . .33 Social Media . 33 Digital Mapping and GIS Laboratory . 33 Databases and Archives . 34 Earth Science Education . 35 Publications and Activities . 37 Publications. .37 Abstracts . 37 Reports . 38 Presentations . .39 Web Products . .41 Operational Improvements . 42 Media Interviews . 42 Professional Activities. .45 Graduate Thesis Committees . 49 Grants and Contracts . .49 Idaho Geological Survey Annual Report—Fiscal Year 2020 INTRODUCTION The Idaho Geological Survey (IGS) is a non-regulatory state agency that leads in the collection, interpretation, and dissemination of geologic and mineral data for Idaho. -

Albion Raft River and Grouse Creek Field Trip Guide

1 THE ALBION-RAFT RIVER-GROUSE CREEK METAMORPHIC CORE COMPLEX: GEOLOGIC SETTING AND FIELD TRIP GUIDE Elizabeth Miller, Ariel Strickland and Alex Konstantinou, Dept. Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University (Revised from: Elizabeth Miller and Ariel Strickland, 2007 Stanford Field Trip to ARG. Caution: Not necessarily accurate or up-to-date!!!!) Introduction The Albion-Raft River-Grouse Creek metamorphic core complex (ARG) is part of a chain of Cordilleran metamorphic core complexes that lie to the west of the Sevier fold- and-thrust belt (Fig. 1). The ARG is made up of three mountain ranges for which it is named (Fig. 2). The Albion Mountains and Grouse Creek Mountains are characteristic of mountain ranges in the Basin and Range Province; they have a generally north-south orientation and rise abruptly from the surrounding relatively flat topography. The Raft River Mountains have an enigmatic east-west trend and project eastward from the northern end of the Grouse Creek Mountains (Fig. 2). Late Archean crystalline basement is exposed in all three mountain ranges indicating a broad dome or structural culmination beneath this region, where probably 10-15 km minimum of relative vertical uplift (compared to surrounding regions) has occurred. In addition, significant thinning of the overlying upper part of the crust characterizes the geology of this core complex. Eocene and Oligocene granitic plutons are exposed in these ranges and based on geologic relations and cross-sections, most likely underlie much of the ARG. The ARG is unique in the Basin and Range because it is bound on both of its sides (east and west) by normal fault systems and their associated basins. -

Burley Field Office Middle Mountain Plan of Operations Draft

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT EA No. DOI-BLM-ID-T020-2012-0015-EA Middle Mountain POO’s Serial/Project No.: IDI-33744, IDI-36013 Field Office: Burley BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Burley Field Office 15 East 200 South Burley, ID 83318 Project Applicants: Oakley Mountain Corporation Gillette Sharp Corporation Burley Field Office Draft Environmental Assessment US Bureau of Land Management 1 Middle Mountain POOs CHAPTER 1, PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Burley Idaho Field Office is considering approval of two Mining Plans of Operations (POOs) submitted by Gillette Sharp Corporation (Gillette) and Oakley Mountain Corporation (Oakley Mountain) to quarry “Oakley Stone,” a micaceous quartzite that is used for decorative surfaces and exterior fascia on buildings and other structures by the construction industry. Uses for Oakley Stone include poolside non-slip surfaces, footpaths, exterior building veneer, and other exterior applications. The proposed quarrying project would be located on public lands within Cassia County, Idaho. Gillette is proposing to quarry, split, palletize, and transport Oakley Stone from an open pit quarry. Oakley Mountain is proposing to quarry and split Oakley Stone from an open pit quarry, and transport it to a millsite approximately two miles west of the quarry. The mill site would be used to split, palletize, and store the stone until it is hauled off-site. Gillette’s quarry and Oakley Mountain’s quarry are immediately adjacent to each other and Oakley Mountain’s mill site is approximately 2 miles west of the quarries (Project Area). The Project Area is generally situated in southern Idaho in unincorporated Cassia County roughly 7 miles south of Oakley and 9 miles north of the Utah-Idaho border (See Map 1). -

Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2014-2015

Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2014-2015 Virginia S. Gillerman Alexis Clark Mark Barton Earl H. Bennett Idaho Geological Survey Morrill Hall, Third Floor Staff Report 21-01 University of Idaho June 2021 Moscow, Idaho 83844-3014 Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2014-2015 Virginia S. Gillerman Alexis Clark Mark Barton Earl H. Bennett Staff Reports present timely information for public distribution. This publication may not conform to the agency’s standards. Idaho Geological Survey Morrill Hall, Third Floor Staff Report 21-01 University of Idaho June 2021 Moscow, Idaho 83844-3014 2 3 Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………...5 Metal Mining ………………………………………………………………………….....8 Phosphate Mining ………………………………………………………………………11 Other Industrial Minerals ………………………………………………………………13 Energy ………………………………………………………………………………….15 Mineral Exploration ……………………………………………………..……………..21 Illustrations Figure 1. Location of mines and active plants in 2014 and 2015………………………..7 Figure 2. Idaho non-fuel mineral production by year 2006 through 2015.……………...8 Figure 3. Map of the Coeur d’Alene district, or Silver Valley…………………………..9 Figure 4. View of # 4 shaft at Hecla’s Lucky Friday mine ………………………..…..10 Figure 5. Thompson Creek mine, September 2014…………………………………….11 Figure 6. Map of Southeast Idaho Phosphate District………………………………….12 Figure 7. Agrium’s Conda phosphate processing plant, 2015………………………….13 Figure 8. Map of Idaho’s industrial mineral locations, 2015…………………………..14 Figure 9. Map of potential oil and gas regions and wells in Idaho…………………….18 Figure 10. Location map of Idaho exploration projects in 2014 and 2015…………….21 Figure 11. Exploration drill, Lucky Friday mine, 6500 level, 2014…………………...23 Figure 12. Portal work, Golden Chest mine, 2014…………………………………….23 Figure 13. New Jersey Mining drilling at McKinley mine……………………………24 Figure 14. -

Ihaarlfs01\Research\OHA Research Library\D

UNITED STATES v. LYLE I. THOMPSON, ET AL. 168 IBLA 64 Decided March 16, 2006 Editors Note: Appeal Filed, No. CV-06-237-E-BLW, (D. Idaho), aff’d, Thompson v. U.S. Dept. of Interior, 2008 WL 564710 (D. Idaho 2008). Appeal Filed, No. 08-35260, (C.A. 9 (Idaho), aff’d, Thompson v. U.S. Department of the Interior, 2009 WL 1974608 (C.A. 9 (Idaho)) June 16, 2009. United States Department of the Interior Office of Hearings and Appeals Interior Board of Land Appeals 801 N. Quincy St., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22203 UNITED STATES v. LYLE I. THOMPSON, ET AL. IBLA 2002-414 Decided March 16, 2006 Appeal from a decision by Administrative Law Judge James H. Heffernan declaring the Tin Cup #12, #13, and #14 mining claims valid, the Tincup #16 mill site claim valid, and the Tincup #17 mill site claim invalid. IMC 166557-59, 166561-62. Mineral Patent Application IDI-28704. Affirmed in part as modified, and reversed in part. 1. Administrative Procedure: Adjudication--Contests and Protests: Government Contests--Evidence: Presumptions-- Mining Claims: Contests--Rules of Practice: Government Contests--Rules of Practice: Appeals: Jurisdiction Where BLM’s administrative record does not contain a date-stamped copy verifying that BLM timely received contestees’ answer to a Government contest complaint, but the record contains substantial corroborating evidence establishing that it is more probable than not that the document was received timely, the legal presumption of regularity, which would ordinarily operate to force a conclusion that the Answer was untimely, is rebutted, and the Office of Hearings and Appeals retains jurisdiction to adjudicate the contest. -

BLM Northern Stone Granite Quarry EA

FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT EA No. DOI-BLM-ID-T020-2015-0008-EA Northern Stone Granite Quarry Serial/Project No.: IDI-33978 Field Office: Burley BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Burley Field Office 15 East 200 South Burley, ID 83318 Project Applicants: Northern Stone Supply, Inc. Burley Field Office Final Environmental Assessment US Bureau of Land Management 1 Northern Stone Granite Quarry CHAPTER 1, PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Burley Idaho Field Office is considering whether to approve a Mining Plan of Operations (POO) submitted by Northern Stone Supply, Inc. (Northern) to quarry granite building stone that is used for decorative surfaces and exterior fascia on buildings and other structures by the construction industry. The proposed quarrying project would be located on public and private lands within Cassia County, Idaho. Northern is proposing to quarry, split, palletize, and transport the granite from an open pit quarry. The Project Area is generally situated in southern Idaho in unincorporated Cassia County roughly 9 miles south of Oakley and 8 miles north of the Utah-Idaho border (See Map 1). Access to the project area is from a gravel road that intersects the Goose Creek Road. This gravel quarry access road travels east and crosses federal, state, and private lands. The BLM-Burley Field Office administers the federal lands in which quarrying operations take place. A common variety determination of the granite produced from Northern’s quarry was performed in 2002 and the granite was found to be locatable. The granite mined at this quarry is a gneissic granite that was found to have unique qualities that include cleavability and dip slope that enable the granite to be used as veneer (unlike other granites) and to allow it to bring a higher price in the market place. -

Chris Miller Was In

SEPTEMBER 2020 VOLUME 26.9 THE BEACON OF THE STONE INDUstRY www.slipperyrockgazette.net recalled Chris, “and pretty much Perpetual Excellence at the by high school age I was consid- ering some kind of career as an Chris Miller Studio artist. I just wasn’t sure of what medium. Then, at about age sev- you’ve ever explored Peter J. Marcucci enteen, I started woodcarving. IF the beauty and charm Photos by Paul Rogers and “Pretty early in my career, I that’s found in small-town Chris Miller Studio opened my first studio at age Vermont, chances are you've eighteen in southern Vermont ex- visited Vermont's State Capitol, clusively doing wood sculpture. Montpelier. Located just a stone's Chris Miller is a seasoned vet- However, I had always wanted throw from Montpelier is the eran with hammer and chisel, and to try stone, and a few years after town of Calais, the home of the has been creating art since child- opening the studio I went to visit Kent Museum and the Robinson hood, and sculpture since 1976. the Vermont quarries. What’s the Saw Mill. It’s also the home of Mostly self-taught, Chris was old saying: ‘When in Rome, do the renowned Chris Miller Studio. influenced by many local artists, as the Romans’? So, after many including the late Billy Brauer years of doing exclusively wood, of Warren, Vermont, and the it was nice to try a different ma- late Lothar Werslin of Sandgate, terial and the techniques used to Vermont. It’s noteworthy to men- carve it, and it was a great mid-ca- tion that Chris’ studio is conve- reer challenge to add stone to the niently close to the Rock of Ages mix.