The Art of Travel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A St. Helena Who's Who, Or a Directory of the Island During the Captivity of Napoleon

A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO ARCHIBALD ARNOTT, M.D. See page si. A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO OR A DIRECTORY OF THE ISLAND DURING THE CAPTIVITY OF NAPOLEON BY ARNOLD gHAPLIN, M.D. (cantab.) Author of The Illness and Death of Napoleon, Thomas Shortt, etc. NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY LONDON : ARTHUR L. HUMPHREYS 1919 SECOND EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED PREFACE The first edition of A St. Helena Whos Wlio was limited to one hundred and fifty copies, for it was felt that the book could appeal only to those who were students of the period of Napoleon's captivity in St. Helena. The author soon found, however, that the edition was insuffi- cient to meet the demand, and he was obliged, with regret, to inform many who desired to possess the book that the issue was exhausted. In the present edition the original form in which the work appeared has been retained, but fresh material has been included, and many corrections have been made which, it is hoped, will render the book more useful. vu CONTENTS PAQI Introduction ....... 1 The Island or St. Helena and its Administration . 7 Military ....... 8 Naval ....... 9 Civil ....... 10 The Population of St. Helena in 1820 . .15 The Expenses of Administration in St. Helena in 1817 15 The Residents at Longwood . .16 Topography— Principal Residences . .19 The Regiments in St. Helena . .22 The 53rd Foot Regiment (2nd Battalion) . 22 The 66th Foot Regiment (2nd Battalion) . 26 The 66th Foot Regiment (1st Battalion) . 29 The 20th Foot Regiment . -

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

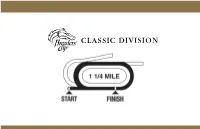

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Lincoln Village

Approximate boundaries: N-W. Becher St; S-W. Harrison Ave; E-I-94 Freeway; W-S. 16th St SOUTH SIDELincoln Village NEIGHBORHOOD DESCRIPTION Lincoln Village is a residential neighborhood with modest homes and strong commercial corridors along West Lincoln Avenue, South 6th Street, and South 16th Street. It is rare to see a commercial building unoccupied and vacant lots simply do not exist in the business district. The corridors truly house “mom and pop” shops. The stores Todays neighborhood- The Basilica of St. Josaphat are small by comparison to other neighborhoods, and tend to have long-term occupants. There are nearly 20 ethnic restaurants or delis along these blocks, representing Mexican, Salvadoran, Serbian, and Polish food. Two architectural styles are of note in Lincoln Village. One style is commercial, where walls extend above the roof of the buildings and are called parapets (see photos below). These can be angular or curved, and represent an architectural style that was brought from northern Poland to the neighbor- hood. The style had originally been developed by the Danes, then brought to Germany, and the Germans erected buildings with parapets in northern Poland. The other architecture style of note is residential, and is called the “Polish flat.” This developed at the grassroots. Most Poles who arrived in Milwaukee were intent on home and land ownership. Often their first paychecks went toward purchasing narrow lots where they would build three to four room cottages. However, as families grew and more relatives arrived, the homeowners lacked space on the lots to enlarge the homes. Often they raised the cottages and replaced the wood foundations with brick or cement block. -

1502-1629 THOUGH It Did Not Take Place Until Fifteen Years Later, the Discovery of St

CHAPTER I 1502-1629 THOUGH it did not take place until fifteen years later, the discovery of St. Helena became inevitable AL when the Portuguese navigator, Bartholomew de Diaz, rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487. For many years the Portuguese, the greatest race of sailors who ever ventured into uncharted seas, excluded from the Mediterranean, had gradually explored farther and farther along the mysterious unmapped western coast of Africa. Ten years after the epoch-making discovery of Diaz and after Columbus and Cabot had opened up the Atlantic to the races of the West and North of Europe, the King of Portugal, Emmanuel the Fortunate, sent out a fleet under the command of Vasco da Gama with orders to sail beyond the Cape of Good Hope in search of a direct sea route to India and thus tap the wealth of the East. Hitherto for centuries all trade between Europe and the East had been carried overland across Arabia, and by ship along the Mediterranean, and had been in the hands of the Italian cities of Venice and Genoa. Da Gama achieved his ambition, and arrived at Calicut, on the west coast of the Indian Peninsula, and from that day the Mediterranean, which for centuries had been the centre of civilization, began to decline. The Portuguese lost no time in building forts and setting up trading posts along the west coast of India, but their principal one was at Calicut. I 5 021 ST. HELENA ST. HELENA [1502 It is not to be wondered at that the "Moors" or Arabs who by some strange fluke of fortune, is still existing and to be for centuries had held the monopoly of the trade between found in considerable numbers. -

Keesep Starts Sunday, Right on Time

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2020 KEESEP STARTS SUNDAY, BREEDERS= CUP BACK TO KEENELAND IN 2022, PURSES MAINTAINED IN 2020 RIGHT ON TIME The Breeders= Cup will return to Keeneland Race Course in Lexington, Ky. as the host site for the 2022 Breeders= Cup World Championships, the Breeders= Cup announced Saturday. Keeneland, which is also scheduled to host this year=s World Championships Nov. 6-7, will hold the 39th Breeders= Cup Nov. 4-5, 2022. It will be the third time the Breeders= Cup has been held at Keeneland since 2015. Del Mar will remain the host of the 2021 event. The announcement of Keeneland as host of the 2022 championships was made in conjunction with two other pieces of news: first, attendance at this year=s event will be limited to the connections of race participants and essential staff, and without fans on-site, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Cont. p6 Keeneland sales grounds | Keeneland photo IN TDN EUROPE TODAY by Jessica Martini MAGICAL TAKES CHAMPION THRILLER LEXINGTON, KY - While the coronavirus pandemic wreaked Magical (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) turned the tables on Ghaiyyath havoc with sales across the globe from March through August, (Ire) (Dubawi {Ire}) to record back-to-back wins in the G1 Irish the calendar will return to some semblance of normalcy when Champion S. the Keeneland September Yearling Sale kicks off right on Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. schedule in Lexington Sunday at noon. ASo many sales companies in the Northern Hemisphere have had to rearrange some things, but we have been very fortunate that the September sale is taking place in September at Keeneland,@ said Keeneland=s Director of Sales Operations Geoffrey Russell. -

Brexit Referendum in Gibraltar. Result and Effect Northern Ireland7 with the Average Turnout of 70,9%

Białostockie Studia Prawnicze 2019 vol. 24 nr 1 DOI: 10.15290/bsp.2019.24.01.07 Bartłomiej H. Toszek University of Szczecin [email protected] ORCID ID: http://orcid.org/ 0000-0003-2989-7168 Brexit Referendum in Gibraltar. Result and Eff ect Abstract: Almost complete unanimity of the small Gibraltar community during 2016 referendum on Brexit remained nearly unnoticed because of including this British Overseas Territory into “combined electoral region” with South West England where most of people were in favour of the United Kingdom withdrawing from the European Union. No political diff erences with the UK (i.e. England and Wales) but concern about future possibilities of economic development outside the Single Market stimulated an intense discussion among the Gibraltarians. Th e vision of being non-subject of the EU’s four freedoms (i.e. damage or lost present prosperity basis) would force Gibraltar to re-orientate its economic relations especially by creating and developing new trade links which could gradually replace the existing ones. Despite that Gibraltarians have consequently rejected Spanish proposals of remaining inside the Single Market for the price of sharing sovereignty between the UK and Spain. It is therefore beyond doubt that the people of Gibraltar can be characterised as more British than European. Keywords: Brexit, European Union, Gibraltar, United Kingdom Th e specifi city of Gibraltar’s referendum on Brexit expressed itself not only because it was the fi rst time for any British Overseas Territory (BOT) to participate in the United Kingdom-wide referendum but also because the Gibraltarians were straight included in the decision-making process related to one of the most important question in the UK’s modern history. -

Panel Listing

Panel Listing Abdus A Financial Services & Investment Banking professional, majoring in Rujubali Business & Finance as well as Economics, with more than 22 years of industry experience, having worked for a number of top financial institutions in various locations globally, namely Lehman Brothers, Standard Chartered Bank & Barclays Capital in London, New York, Tokyo and Singapore. Strong technical expertise in various traditional investment banking products as well as front to back operations knowledge, a keen supporter and advocator of new technologies and innovations (like Blockchain) that can be used in the financial markets which will enable financial inclusion and create more financial equality. Addy Crezee Bitcoin/Blockchain Enthusiast since 2013. 2014 has become the year of changes when I entered the doors of CoinTelegraph. I was working as the CMO and tried to show my best in developing growth, sales and marketing. In August 2015 I founded my own project Investors' Angel - Blockchain Investments Consultancy agency. Investors' Angel has helped to raise $800k for Blockchain-oriented startups up to this moment. Since August 2016 I have become the CEO at Blockshow by Cointelegraph focused on creating an international platform for founders to showcase their Blockchain solutions. Adrian Yeow Dr. Adrian Yeow is currently a Senior Lecturer at School of Business, Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) where he teaches Accounting Information Systems and Accounting Analytics courses for the full-time Accounting programme. He earned his Ph.D. from R.H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland, College Park in 2008. Adrian's research and consulting work focuses on the implementation and use of business systems in accounting, healthcare, and financial settings. -

Brexit: Gibraltar

HOUSE OF LORDS European Union Committee 13th Report of Session 2016–17 Brexit: Gibraltar Ordered to be printed 21 February 2017 and published 1 March 2017 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 116 The European Union Committee The European Union Committee is appointed each session “to scrutinise documents deposited in the House by a Minister, and other matters relating to the European Union”. In practice this means that the Select Committee, along with its Sub-Committees, scrutinises the UK Government’s policies and actions in respect of the EU; considers and seeks to influence the development of policies and draft laws proposed by the EU institutions; and more generally represents the House of Lords in its dealings with the EU institutions and other Member States. The six Sub-Committees are as follows: Energy and Environment Sub-Committee External Affairs Sub-Committee Financial Affairs Sub-Committee Home Affairs Sub-Committee Internal Market Sub-Committee Justice Sub-Committee Membership The Members of the European Union Select Committee are: Baroness Armstrong of Hill Top Baroness Kennedy of The Shaws Lord Trees Lord Boswell of Aynho (Chairman) Earl of Kinnoull Baroness Verma Baroness Brown of Cambridge Lord Liddle Lord Whitty Baroness Browning Baroness Prashar Baroness Wilcox Baroness Falkner of Margravine Lord Selkirk of Douglas Lord Woolmer of Leeds Lord Green of Hurstpierpoint Baroness Suttie Lord Jay of Ewelme Lord Teverson Further information Publications, press notices, details of membership, forthcoming meetings and other information is available at http://www.parliament.uk/hleu. General information about the House of Lords and its Committees is available at http://www.parliament.uk/business/lords. -

Bar-Tender's Guide Or How to Mix Drinks

JERRY THOMAS' BAR-TENDERS GUIDE НOW TO MIX DRINKS NEW YORK. DIС AND FITZGERALD, PUBLISHERS. THE BAR-TENDERS GUIDE; OR, HOW TO MIX ALL KINDS OF PLAIN AND FANCY DRINKS, CONTAINING CLEAR AND RELIABLE DIRECTIONS FOB MIXING ALL THE BEVERAGES USED IN THE UNITED STATES, TOGETHER WITH THE MOST POPULAR BRITISH, FRENCH, GERMAN, ITALIAN, EUSSIAN, AND SPANISH RECIPES ; EMBRACING PUNCHES, JULEPS, COBBLERS, ETC., ETC., IN ENDLESS VARIETY. BY JERRY THOMAS, Formerly Principal Bar-Tender at the Metropolitan Hotel, New York, and the Planters' House, 81. Louis. NEW YORK: DICK & FITZGERALD, PUBLISHERS, No. 18 ANN STREET. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1862, by DICK & FITZGERALD, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States, for the Southern District of New York. - Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1876, BY DICK & FITZGERALD, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. PREFACE. In all ages of the world, and in all countries, men have in dulged in "so cial drinks." They have al ways possess ed themselves of some popu lar beverage apart from water and those of the breakfast and tea table. Whether it is judicious that mankind should con tinue to indulge in such things, or whether it would be wiser to abstain from all enjoyments of that character, it is not our province to decide. We leave that question to the moral philosopher. We simply contend that a relish for "social drinks" is universal; that those drinks exist in greater variety in the United States than in any other country in the world; and that he, therefore, who proposes to impart to these drink not only the most palatable but the most wholesome characteristics of which they may be made susceptible, is a genuine public benefactor. -

Øvrevoll Galoppbanen På Facebook

ØVREVOLL GALOPP Hovedsamarbeidspartner 2012 Nr. 24/2012 – Kr. 20,– TORSDAG 20. SEPTEMBER KL. 18.00 Første løp kl. 18.10. V5A: 3.-7. løp. 3 Velkommen til en hyggelig kveld på Øvrevoll! 3 3 Spill i dag Hovedsamarbeidspartner 2012 @ Annette Boe Østergaard @ For hester som hele tiden skal utvikles, er det viktig med et fôr som også gjør det Bak Champion står det et våkent og kunnskapsrikt miljø, som er raske til å ta tilbakemeldinger fra markedet. Den nære kontakten med brukerne, samt det faktum at vi råder over eget fôrutviklingsselskap og avansert kvalitetskontroll, gjør at vi raskt kan omsette nye erfaringer, ny forskning og teknologi, til stadig bedre fôrblandinger for prestasjonshester. Generalsponsor for Anbefalt av Norges Rytterforbund Norges Veterinærhøgskole Øvrevoll Program_Champion_FK.indd 1 20.05.2009 11:15:18 Hans Petter Eriksen Norsk Jockeyklub Postboks 134, 1332 Østerås Vollsveien 132, 1358 Jar Tlf. 22 95 62 00 – Faks 22 95 62 62 Telefon løpsdager 22 95 62 18 www.ovrevoll.no Ragazzo vant Norsk Rikstoto Grand Prix Styret i Norsk Jockeyklub S A Hauge, formann Ragazzo med Espen Ski på ryggen vant lett Norsk Rikstoto Grand N P Gill N Ekjord Prix sist torsdag og viste at annenplassen i Fearnleyløpet ikke var R Molthe S Pedersen et blaff. Ragazzo er oppdrettet av Johan C Løken og eies av Stall M Robertz, Avlsforeningen Trotting. Trener Annike Bye Hansen har vært forsiktig med den S E Lilja, Trenerforeningen S Tangen, storvokste hingsten og det ser ut til å betale seg nå og han blir Øvrevoll Hesteeierforening spennende å følge framover. H L S Marwell-Hauge, NoARK Styret i Øvrevoll Galopp AS B Jacobsen, formann En annen flott vinner torsdag var Stall RH’s Wunschkind som C Skotvedt R Hoel imponerte i toårsløpet. -

Memorinmotion

english memorInmotion pedagogical tool on culture of remembrance manual dvd second supplemented edition MemorInmotion Pedagogical Tool on Culture of Remembrance Second supplemented edition Manual DVD Sarajevo, 2016 Publication Title: Consultants: MemorInmotion - Pedagogical Tool on Culture of Suad Alić Remembrance Andrea Baotić Second supplemented edition Judith Brand Elma Hašimbegović Authors: Adis Hukanović Laura Boerhout Alma Mašić Ana Čigon Nerkez Opačin Bojana Dujković-Blagojević Christian Pfeifer Melisa Forić Soraja Zagić Senada Jusić Muhamed Kafedžić Muha Editor-in-chief: Larisa Kasumagić-Kafedžić Michele Parente Vjollca Krasniqi Nita Luci Project Coordinators: Nicolas Moll Michele Parente, forumZFD Michele Parente Melisa Forić, EUROCLIO HIP BiH Wouter Reitsema Laura Boerhout, Anne Frank House (Netherlands) Students of the PI Gymnasium Obala, Sarajevo CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo 791.5:725.94(497) MEMORLNMOTION : pedagogical tool on culture of remembrance : manual / [authors Melisa Forić ... [et al.] ; translators Lejla Efendić, Gordana Lonco]. - 2nd supplemented ed. - Sarajevo : Forum Ziviler Friedensdienste e.V. (forumZFD), 2016. - 101 str. : ilustr. ; 20 x 20 cm + [1] DVD Prijevod djela: Sjećanje u pokretu. - The authors: str. 93-96. - Bibliografija: str. 97-100 ISBN 978-9958-0399-6-6 1. Forić, Melisa COBISS.BH-ID 23297286 contents I. Manual 1.0. Introduction 1.1. Memorlnmotion - Pedagogical Tool on Culture of Remembrance 7 2.0. Essay: how to create an active culture of remembrance in our societies? 2.1. Challenging young people to reflect on monuments and their meaning 11 3.0. The pedagogical modules with lesson plans 3.1. Module I: Start-up 3.1.1. Lesson Plan 1: Who am I? 17 3.2.