Public Development for Professional Sports Stadiums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF of Aug 15 Results

Huggins and Scott's August 6, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Incredible 1911 T205 Gold Borders Near Master Set of (221/222) SGC Graded Cards--Highest SGC Grade Average!5 $ [reserve - not met] 2 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Cap Anson SGC 55 VG-EX+ 4.5 22 $ 3,286.25 3 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Jocko Fields SGC 80 EX/NM 6 4 $ 388.38 4 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Cliff Carroll SGC 80 EX/NM 6--"1 of 1" with None Better 8 $ 717.00 5 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Kid Gleason SGC 50 VG-EX 4--"Black Sox" Manager 4 $ 448.13 6 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Dan Casey SGC 80 EX/NM 6 7 $ 418.25 7 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Mike Dorgan SGC 80 EX/NM 6 8 $ 448.13 8 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Sam Smith SGC 50 VG-EX 4 17 $ 776.75 9 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Joe Gunson SGC 50 VG-EX 4 6 $ 239.00 10 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Henry Gruber SGC 40 VG 3 4 $ 155.35 11 1887 N172 Old Judge Cigarettes Bill Hallman SGC 40 VG 3 6 $ 179.25 12 1888 Scrapps Die-Cuts St. Louis Browns SGC Graded Team Set (9) 14 $ 896.25 13 1909 T204 Ramly Clark Griffith SGC Authentic 6 $ 239.00 14 1909-11 T206 White Borders Sherry Magee (Magie) Error--SGC Authentic 13 $ 3,585.00 15 1909-11 T206 White Borders Bud Sharpe (Shappe) Error--SGC 45 VG+ 3.5 10 $ 1,912.00 16 (75) 1909-11 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards with (12) Hall of Famers & (6) Southern Leaguers 16 $ 2,987.50 17 1911 T206 John Hummel American Beauty 460 --SGC 55 VG-EX+ 4.5 14 $ 358.50 18 Incredible 1909 S74 Silks-White Ty Cobb SGC 84 NM 7 with Red Sun Advertising Back--Highest Graded Known8 from$ 5,078.75 Set! 19 (15) 1909-11 T206 White Border SGC 30-55 Graded Cards with Jimmy Collins 15 $ 597.50 20 1921 Schapira Brothers Candy Babe Ruth (Portrait) SGC 40 VG 3 18 $ 448.13 21 1926-29 Baseball Exhibits-P.C. -

CSL Economic Analysis

NFL Funding Comparison Total Private Funding Public Funding Year Project Total % of Total % of Stadium/Team Team Opened Cost Private Total Public Total Los Angeles Stadium (Proposed) TBD 2016 $1,200.0 $1,200.0 100% $0.0 0% San Francisco 49ers (Proposed) San Francisco 49ers 2015 $987.0 $873.0 88% $114.0 12% New Meadowlands Stadium Giants/Jets 2010 $1,600.0 $1,600.0 100% $0.0 0% New Cowboys Stadium Dallas Cowboys 2009 $1,194.0 $750.0 63% $444.0 37% Lucas Oil Stadium Indianapolis Colts 2008 $675.0 $100.0 15% $575.0 85% University of Phoenix Stadium Arizona Cardinals 2006 $471.4 $150.4 32% $321.0 68% Lincoln Financial Field Philadelphia Eagles 2003 $518.0 $330.0 64% $188.0 36% Soldier Field (renovation) Chicago Bears 2003 $587.0 $200.0 34% $387.0 66% Lambeau Field (renovation) Green Bay Packers 2003 $295.2 $126.1 43% $169.1 57% Gillette Stadium New England Patriots 2002 $412.0 $340.0 83% $72.0 17% Ford Field Detroit Lions 2002 $440.0 $330.0 75% $110.0 25% Reliant Stadium Houston Texans 2002 $474.0 $185.0 39% $289.0 61% Qwest Field Seattle Seahawks 2002 $461.3 $161.0 35% $300.3 65% Heinz Field Pittsburgh Steelers 2001 $280.8 $109.2 39% $171.6 61% Invesco Field at Mile High Denver Broncos 2001 $400.8 $111.8 28% $289.0 72% Paul Brown Stadium Cincinnati Bengals 2000 $449.8 $25.0 6% $424.8 94% LP Field Tennessee Titans 1999 $291.7 $84.8 29% $206.9 71% Cleveland Browns Stadium Cleveland Browns 1999 $271.0 $71.0 26% $200.0 74% M&T Bank Stadium Baltimore Ravens 1998 $226.0 $22.4 10% $203.6 90% Raymond James Stadium Tampa Bay Buccaneers 1998 $194.0 -

Ticket Sales Report

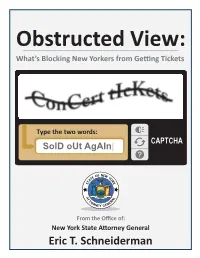

Obstructed View: What’s Blocking New Yorkers from Geng Tickets Type the two words: CAPTCHA SolD oUt AgAIn| From the Office of: New York State Aorney General Eric T. Schneiderman 1 This report was a collaborative effort prepared by the Bureau of Internet and Technology and the Research Department, with special thanks to Assistant Attorneys General Jordan Adler, Noah Stein, Aaron Chase, and Lydia Reynolds; Director of Special Projects Vanessa Ip; Researcher John Ferrara; Director of Research and Analytics Lacey Keller; Bureau of Internet and Technology Chief Kathleen McGee; Chief Economist Guy Ben-Ishai; Senior Enforcement Counsel and Special Advisor Tim Wu; and Executive Deputy Attorney General Karla G. Sanchez. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................... 3 The History of, and Policy Behind, New York’s Ticketing Laws ....... 7 Current Law ................................................................................... 9 Who’s Who in the Ticketing Industry ........................................... 10 Findings ....................................................................................... 11 A. The General Public Loses Out on Tickets to Insiders and Brokers .................................................................... 11 1. The Majority of Tickets for Popular Concerts Are Not Reserved For the General Public .......................................................................... 11 2. Brokers & Bots Buy Tickets in Bulk, Further Crowding Out Fans ...... 15 -

PRO FOOTBALL HALL of FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 Edition

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 EDITIOn Quarterback Joe Namath - Hall of fame class of 1985 nEW YORK JETS Team History The history of the New York franchise in the American Football League is the story of two distinct organizations, the Titans and the Jets. Interlocking the two in continuity is the player personnel which went with the franchise in the ownership change from Harry Wismer to a five-man group headed by David “Sonny” Werblin in February 1963. The three-year reign of Wismer, who was granted a charter AFL franchise in 1959, was fraught with controversy. The on-the-field happenings of the Titans were often overlooked, even in victory, as Wismer moved from feud to feud with the thoughtlessness of one playing Russian roulette with all chambers loaded. In spite of it all, the Titans had reasonable success on the field but they were a box office disaster. Werblin’s group purchased the bankrupt franchise for $1,000,000, changed the team name to Jets and hired Weeb Ewbank as head coach. In 1964, the Jets moved from the antiquated Polo Grounds to newly- constructed Shea Stadium, where the Jets set an AFL attendance mark of 45,665 in the season opener against the Denver Broncos. Ewbank, who had enjoyed championship success with the Baltimore Colts in the 1950s, patiently began a building program that received a major transfusion on January 2, 1965 when Werblin signed Alabama quarterback Joe Namath to a rumored $400,000 contract. The signing of the highly-regarded Namath proved to be a major factor in the eventual end of the AFL-NFL pro football war of the 1960s. -

NCAA Division II-III Football Records (Special Games)

Special Regular- and Postseason- Games Special Regular- and Postseason-Games .................................. 178 178 SPECIAL REGULAR- AND POSTSEASON GAMES Special Regular- and Postseason Games 11-19-77—Mo. Western St. 35, Benedictine 30 (1,000) 12-9-72—Harding 30, Langston 27 Postseason Games 11-18-78—Chadron St. 30, Baker (Kan.) 19 (3,000) DOLL AND TOY CHARITY GAME 11-17-79—Pittsburg St. 43, Peru St. 14 (2,800) 11-21-80—Cameron 34, Adams St. 16 (Gulfport, Miss.) 12-3-37—Southern Miss. 7, Appalachian St. 0 (2,000) UNSANCTIONED OR OTHER BOWLS BOTANY BOWL The following bowl and/or postseason games were 11-24-55—Neb.-Kearney 34, Northern St. 13 EASTERN BOWL (Allentown, Pa.) unsanctioned by the NCAA or otherwise had no BOY’S RANCH BOWL team classified as major college at the time of the 12-14-63—East Carolina 27, Northeastern 6 (2,700) bowl. Most are postseason games; in many cases, (Abilene, Texas) 12-13-47—Missouri Valley 20, McMurry 13 (2,500) ELKS BOWL complete dates and/or statistics are not avail- 1-2-54—Charleston (W.V.) 12, East Carolina 0 (4,500) (at able and the scores are listed only to provide a BURLEY BOWL Greenville, N.C.) historical reference. Attendance of the game, (Johnson City, Tenn.) 12-11-54—Newberry 20, Appalachian St. 13 (at Raleigh, if known, is listed in parentheses after the score. 1-1-46—High Point 7, Milligan 7 (3,500) N.C.) ALL-SPORTS BOWL 11-28-46—Southeastern La. 21, Milligan 13 (7,500) FISH Bowl (Oklahoma City, Okla.) 11-27-47—West Chester 20, Carson-Newman 6 (10,000) 11-25-48—West Chester 7, Appalachian St. -

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects an Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) By Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2004 May 8, 2004 Abstract The history of baseball in the United States during the twentieth century in many ways mirrors the history of our nation in general. When the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left New York for California in 1957, it had very interesting repercussions for New York. The vacancy left by these two storied baseball franchises only spurred on the reason why they left. Urban decay and an exodus of middle class baseball fans from the city, along with the increasing popularity of television, were the underlying causes of the Giants' and Dodgers' departure. In the end, especially in the case of Brooklyn, which was very attached to its team, these processes of urban decay and exodus were only sped up when professional baseball was no longer a uniting force in a very diverse area. New York's urban demographic could no longer support three baseball teams, and California was an excellent option for the Dodger and Giant owners. It offered large cities that were hungry for major league baseball, so hungry that they would meet the requirements that Giants' and Dodgers' owners Horace Stoneham and Walter O'Malley had asked for in New York. These included condemnation of land for new stadium sites and some city government subsidization for the Giants in actually building the stadium. Overall, this research shows the very real impact that sports has on its city and the impact a city has on its sports. -

Base Ball and Trap Shooting

MBfc Tag flMffll ~y^siMf " " f" BASE BALL AND TRAP SHOOTING VOL. 64. NO. 7 PHILADELPHIA, OCTOBER 17, 1914 PRICE 5 CENTS National League Pennant Winners Triumph Over Athletics in Four Straight Games, Setting a New Record for the Series Former Title Holders Are Outclassed, Rudolph and James Each Win Two Games Playing the most sensational and surprising that single tally was the result of a "high l>ase ball ever seen in a World©s Series, the throw to the plate by Collins on a double Boston National League Club won the pre steal. mier base ball honors from the Athletics, Hero of the World©s Series THE DIFFERENCE IN PITCHING champions of the American League in four made the Athletics appear to disadvantage, ©aa straight games, the series closing on October light hitting always does with any team, while 13, in Boston. Never before had any club cap Ithe winning start secured by the Braves tured the World©s Championship in the short made them appear perhaps stronger than the space of four games, and it is doubtful Athletics, on this occasion at least. At any whether in any previous series a former rate they played pretty much the game that World©s Champion team fell away so badly won their league pennant. They fielded with as did the American League title-holders. precision and speed, ran bases with reckless Rudolph and James were the two Boston abandon, and showed courage and aggressive Ditchers who annexed the victories, each tri ness from the moment they gained the lead. -

Design Considerations for Retractable-Roof Stadia

Design Considerations for Retractable-roof Stadia by Andrew H. Frazer S.B. Civil Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of AASSACHUSETTS INSTiTUTE MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN OF TECHNOLOGY CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING MAY 3 12005 AT THE LIBRARIES MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2005 © 2005 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of Author:.................. ............... .......... Department of Civil Environmental Engineering May 20, 2005 C ertified by:................... ................................................ Jerome J. Connor Professor, Dep tnt of CZvil and Environment Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:................................................... Andrew J. Whittle Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies BARKER Design Considerations for Retractable-roof Stadia by Andrew H. Frazer Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 20, 2005 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT As existing open-air or fully enclosed stadia are reaching their life expectancies, cities are choosing to replace them with structures with moving roofs. This kind of facility provides protection from weather for spectators, a natural grass playing surface for players, and new sources of revenue for owners. The first retractable-roof stadium in North America, the Rogers Centre, has hosted numerous successful events but cost the city of Toronto over CA$500 million. Today, there are five retractable-roof stadia in use in America. Each has very different structural features designed to accommodate the conditions under which they are placed, and their individual costs reflect the sophistication of these features. -

Brooklyn-Based Tgi Office Automation Brings Nearly 50 Years of Technology Expertise to Barclays Center

BROOKLYN-BASED TGI OFFICE AUTOMATION BRINGS NEARLY 50 YEARS OF TECHNOLOGY EXPERTISE TO BARCLAYS CENTER TGI Forms Partnership with the Brooklyn Nets and Barclays Center BROOKLYN (September 21, 2012) – Reaffirming their commitment to supporting local businesses, Barclays Center and the Brooklyn Nets have formed an alliance with Brooklyn-based TGI Office Automation, one of the nation’s most reputable office solutions provider. TGI will provide Barclays Center and the Brooklyn Nets with office equipment, including copiers, printers and fax machines. Factory trained service technicians and certified network engineers will be available to provide dedicated around the clock customer service. Environmental sustainability is important to Barclays Center, the Brooklyn Nets and TGI Office Automation. As part of their commitment to the environment, TGI will hold an event during a Brooklyn Nets game to collect empty printer cartridges which will then be recycled in order to keep them out of landfills. “We were thrilled when the opportunity to partner with Barclays Center and the Brooklyn Nets presented itself,” said TGI CEO Frank Grasso. “This partnership gives us the opportunity to connect with the people of Brooklyn in ways we wouldn’t otherwise be able to and provides us with an international stage to showcase what Brooklyn businesses are really all about.” In addition to the recycling program, TGI will provide other ecological solutions, including dramatically reducing paper use, introducing energy star-compliant equipment, and installing software tools to achieve and measure carbon footprint. “Barclays Center and the Brooklyn Nets are proud to align with TGI Office Automation, a Brooklyn-based business,” said Barclays Center and Brooklyn Nets CEO Brett Yormark. -

2012-13 Men's Basketball

2012-13 MEN’S BASKETBALL SCHEDULE (AS OF DEC. 6) DAY DATE OPPONENT LOCATION TIME TV Sat. Nov. 3 SONOMA STATE (Exh.) Queens, N.Y. (Carnesecca Arena) 5:30 p.m. ESPN3 Tues. Nov. 6 CONCORDIA (ILL.) (Exh.) Queens, N.Y. (Carnesecca Arena) 7:30 p.m. ESPN3 Tues. Nov. 13 DETROIT Queens, N.Y. (Carnesecca Arena) 2 p.m. ESPN DIRECTV Charleston Classic presented by Foster Grant Thurs. Nov. 15 at Charleston Charleston, S.C. (TD Arena) 5 p.m. ESPNU Fri. Nov. 16 vs. Murray State/Auburn Charleston, S.C. (TD Arena) 5:30/7:30 p.m. ESPN3 Sun. Nov. 18 Championship/Consolation Charleston, S.C. (TD Arena) TBA ESPN2/ESPNU/E3 Participating Teams: St. John’s, Auburn, Baylor, Boston College, Charleston, Colorado, Dayton, Murray State Wed. Nov. 21 HOLY CROSS Queens, N.Y. (Carnesecca Arena) 7:30 p.m. SNY Sat. Nov. 24 FLORIDA GULF COAST Queens, N.Y. (Carnesecca Arena) 7:30 p.m. ESPN3 SEC/BIG EAST Challenge Thurs. Nov. 29 SOUTH CAROLINA Queens, N.Y. (Carnesecca Arena) 7:30 p.m. ESPNU Sat. Dec. 1 NJIT Queens, N.Y. (Carnesecca Arena) 1 p.m. ESPN3 Tues. Dec. 4 at San Francisco San Francisco, Calif. (War Memorial Gym) 10 p.m. SNY Madison Square Garden Holiday Festival presented by Foot Locker Sat. Dec. 8 FORDHAM New York, N.Y. (Madison Square Garden) 7 p.m. MSG+ Rutgers vs. Iona New York, N.Y. (Madison Square Garden) 9:30 p.m. MSG+ BROOKLYN HOOPS Winter Festival Sat. Dec. 15 Fordham vs. Princeton Brooklyn, N.Y. -

St Charles Parks Department “Cardinals Vs Indians in Cleveland” July 26-30, 2021 Itinerary

St Charles Parks Department “Cardinals vs Indians in Cleveland” July 26-30, 2021 Itinerary Monday, July 26, 2021 6:30am Depart Blanchette Park, St Charles for Indianapolis, IN with rest stop for coffee and donuts in route. 8:15am Rest stop at Flying J Travel Center with coffee & donuts. Flying J Travel Center 1701 W. Evergreen Ave Effingham, IL 62401 8:45am Depart for Indianapolis, IN Move clocks forward one hour to Eastern Daylight Saving Time. 12:00pm-1:00pm Lunch at McAlister’s Deli ~Lunch on Your Own~ McAlister’s Deli 9702 E. Washington St Indianapolis, IN 46229 Phone: 317-890-0500 1:00pm Depart for Dublin, OH 3:40pm Check into overnight lodging for one-night stay. Drury Inn & Suites--Columbus Dublin 6170 Parkcenter Circle Dublin, OH 43017 Phone: 614-798-8802 5:00pm Depart for dinner 5:30pm-7:30pm Dinner tonight at Der Dutchman Der Dutchman 445 S. Jefferson Route 42 Plain City, OH 43064 Phone: 614-873-3414 Menu Family Style Entrée: Broasted Chicken, Roast Beef, & Ham Sides: Salad Bar, Mashed Potatoes, Dressing, Corn, Noodles Beverage: Non-alcoholic Drink Dessert: Slice of Pie 7:30pm Return to Drury Inn & Suites-Dublin 1 Tuesday, July 27, 2021 6am-7:30am Breakfast at our hotel at your leisure 6:30am Bags down by the bus for loading 7:30am Depart for Akron, OH 9:30am-12:00am Enjoy a guided tour of the Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens. ~Box Lunch Furnished~ Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens 714 N. Portage Path Akron, OH 44303 Phone: 330836-5533 In 1910, F.A. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally.