Postmodernism and Gender Relations in Feminist Theory.‖ Within and Without: Women, Gender, and Theory, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones

Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Gloria Makjanić Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Zadar, 2018. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Gloria Makjanić dr. sc. Zlatko Bukač Zadar, 2018. Makjanić 1 Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Gloria Makjanić, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Female Archetypes of Game of Thrones rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 13. rujna 2018. Makjanić 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. Game of Thrones ............................................................................................................. 4 3. Archetypes ...................................................................................................................... -

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline . -

Game of Thrones Season Six Trading Cards Checklist

Game of Thrones Season Six Trading Cards Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 001 The Red Woman [ ] 002 The Red Woman [ ] 003 The Red Woman [ ] 004 Home [ ] 005 Home [ ] 006 Home [ ] 007 Oathbreaker [ ] 008 Oathbreaker [ ] 009 Oathbreaker [ ] 010 Book of the Stranger [ ] 011 Book of the Stranger [ ] 012 Book of the Stranger [ ] 013 The Door [ ] 014 The Door [ ] 015 The Door [ ] 016 Blood of My Blood [ ] 017 Blood of My Blood [ ] 018 Blood of My Blood [ ] 019 The Broken Man [ ] 020 The Broken Man [ ] 021 The Broken Man [ ] 022 No One [ ] 023 No One [ ] 024 No One [ ] 025 Battle of the Bastards [ ] 026 Battle of the Bastards [ ] 027 Battle of the Bastards [ ] 028 The Winds of Winter [ ] 029 The Winds of Winter [ ] 030 The Winds of Winter [ ] 031 Tyrion Lannister [ ] 032 Ser Jaime Lannister [ ] 033 Cersei Lannister [ ] 034 Daenerys Targaryen [ ] 035 Jon Snow [ ] 036 Petyr "Littlefinger" Baelish [ ] 037 Queen Margaery [ ] 038 Ser Davos Seaworth [ ] 039 Melisandre [ ] 040 Ellaria Sand [ ] 041 Sansa Stark [ ] 042 Sandor Clegane "The Hound" [ ] 043 Missandei [ ] 044 Arya Stark [ ] 045 Lord Varys [ ] 046 Theon Greyjoy [ ] 047 Samwell Tarly [ ] 048 King Tommen Baratheon [ ] 049 Brienne of Tarth [ ] 050 Bronn [ ] 051 Bran Stark [ ] 052 Tormund Giantsbane [ ] 053 Daario Naharis [ ] 054 Roose Bolton [ ] 055 Gilly [ ] 056 High Sparrow [ ] 057 Ramsay Bolton [ ] 058 Jaqen H'ghar [ ] 059 Ser Jorah Mormont [ ] 060 Grey Worm [ ] 061 Waif [ ] 062 Ser Gregor Clegane [ ] 063 Yara Greyjoy [ ] 064 Lady Olenna Tyrell [ ] 065 Eddison Tollett [ ] 066 Podrick Payne -

Game of Thrones Season 7 Directors Revealed | EW.Com

Game of Thrones season 7 directors revealed It’s the first official news about Game of Thrones season 7: The next outing of the international fantasy sensation has lined up four acclaimed directors to tackle the 2017 season – including a founding Thrones veteran who’s returning to the show after directing major Hollywood films. The first thing savvy Thrones fans will notice about this list is the number of names. In recent years, Thrones has employed five directors to helm two episodes each. HBO has not yet publicly confirmed the plan by Thrones showrunners David Benioff and Dan Weiss to reduce next season to seven episodes. But given that there are fewer directors on board for season 7, viewers can take that as a sign that things will be different next year. Here are the directors signed on for season 7: – Alan Taylor: An Emmy-winning veteran of The Sopranos, Taylor helped pioneer the visual storytelling style of the show when he helmed the pivotal ninth and 10th episodes of season 1, particularly “Baelor” (the episode where Ned Stark was executed). The Thrones producers were so impressed they gave Taylor four episodes to helm in season 2 – including the premiere and the finale. Then Marvel snatched him up for Thor: The Dark World followed by Taylor reuniting with Emilia Clarke to direct her big-screen role in Terminator: Genisys. Now he’s back on Thrones for the first time since 2012. – Jeremy Podeswa: The Canadian director and Boardwalk Empire veteran scored an Emmy nomination for directing the show’s most controversial hour, season 5’s darkly tense “Unbowed, Unbent, Unbroken.” This year he directed the propulsive season premiere as well as Jon Snow’s riveting resurrection episode, “Home.” – Mark Mylod: A four-time director on the show, the British veteran of Showtime’s Shameless and HBO’s Entourage took on this season’s uniquely textured re-introduction of the The Hound in “The Broken Man,” as well as Arya’s exciting chase sequence in “No One.” – Matt Shakman: A newcomer to the series. -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

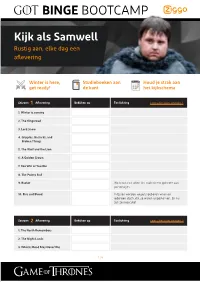

Binge Bootcamp

BINGE BOOTCAMP Kijk als Samwell Rustig aan, elke dag een aflevering Winter is here, Studieboeken aan Houd je strak aan get ready! de kant het kijkschema Seizoen1 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 1 1. Winter is coming 2. The Kingsroad 3. Lord Snow 4. Cripples, Bastards, and Broken Things 5. The Wolf and the Lion 6. A Golden Crown 7. You Win or You Die 8. The Pointy End 9. Baelor We leren een wijze les: raak niet te gehecht aan personages. 10. Fire and Blood In Essos worden wezens geboren waarvan iedereen dacht dat ze waren uitgestorven. En nu zijn ze nog cute! Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 1. The North Remembers 2. The Night Lands 3. What is Dead May Never Die 1 /4 BINGE BOOTCAMP Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 4. Garden of Bones 5. The Ghost of Harranhal 6. The Old Gods and the New 7. A Man Without Honor 8. The Prince of Winterfell 9. Blackwater King’s Landing, de hoofdstad van de Seven Kingsdoms, wordt aangevallen. Wat volgt is episch. 10. Valar Morghulis Seizoen3 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 3 1. Valar Dohaeris 2. Dark Wings, Dark Words 3. Walk of Punishment 4. And Now His Watch is 5. Kissed by Fire 6. The Climb 7. The Bear and the Maiden 8. Second Sons 9. The Rains of Castamere 10. Mhysa Seizoen4 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 4 1. Two Swords 2. The Lion and the Rose Wraak is zoet! 3. -

Star Channels Guide, July 16-22

JULY 16 - 22, 2017 staradvertiser.com GAME IS AFOOT While Jon Snow (Kit Harington) marches off to war in the North, Daenerys Targaryen (Emilia Clarke) sets her sights on reclaiming her birthright in the seventh season of Game of Thrones. Both Jon and Daenerys face a formidable adversary in Queen Cersei (Lena Headey), who is determined to see all her enemies cut down. Premieres Sunday, July 16, on HBO. – HART Board meeting, live on ROlelo THIS THURSDAY, 8:30AM | CHANNEL 49 49 52 53 54 55 www.olelo.org ON THE COVER | GAME OF THRONES All together now Characters converge on Westeros Entertainment Weekly, executive producer Also this season, Jon’s long-lost half-sister, David Benioff explained their approach. Daenerys Targaryen (Emilia Clarke, “Me Before in ‘Game of Thrones’ season 7 “So it’s really about trying to find a way to You,” 2016), crosses the Narrow Sea after make the storytelling work without feeling years in exile in a bid to reclaim her birth- By Kyla Brewer like we’re rushing it — you still want to give the right. She arrives in Westeros alongside her TV Media characters their due, and pretty much all the Dothraki, Unsullied, Dornish, Tyrell and Greyjoy characters that are now left are all important allies — as well as her dragons, of course. The ummer may be kicking into high gear in characters,” Benioff said. Mother of Dragons is poised to take the Iron most parts of the country, but winter is Among the leaders marching off to war is Throne, but first it appears she’ll retake her Sabout to arrive in prime time. -

Season/Episode Name of Episode Watch Meter Season 3/1 Valar

Season/Episode Name of Episode Watch Meter Season 3/1 Valar Dohaeris Must Watch Season 3/2 Dark Wings, Dark Words Season 3/3 Walk of Punishment Watch if you have time Season 3/4 And Now His Watch Has Ended Must Watch Season 3/5 Kissed by Fire Must Watch Season 3/6 The Climb Season 3/7 The Bear and Maiden Fair Watch if you have time Season 3/8 Second Sons Must Watch Season 3/9 Rains of Castamere Must Watch Season 3/10 Mhysa Must Watch Season/Episode Name of Episode Watch Meter Season 4/1 Two Swords Must Watch Season 4/2 Lion and Rose Must Watch Season 4/3 Breaker of Chains Season 4/4 Oath Keeper Season 4/5 First of His Name Watch if you have time Season 4/6 Law of Gods and Men Watch if you have time Season 4/7 Mockingbird Must Watch Season 4/8 The Mountain and the Viper Must Watch Season 4/9 Watchers on the Wall Must Watch Season 4/10 The Children Must Watch Season/Episode Name of Episode Watch Meter Season 5/1 Wars to Come Watch if you have time Season 5/2 House of Black and White Season 5/3 High Sparrow Must Watch Season 5/4 Sons of the Harpy Watch if you have time Season 5/5 Kill the Boy Season 5/6 Unbowed, Unbent, Unbroken Must Watch Season 5/7 The Gift Watch if you have time Season 5/8 Hardhome Must Watch (OMG) Season 5/9 Dance of Dragons Must Watch Season 5/10 Mother’s Mercy Must Watch Season/Episode Name of Episode Watch Meter Season 6/1 The Red Woman Must Watch Season 6/2 Home Must Watch Season 6/3 Oathbreaker Must Watch Season 6/4 Book of the Stranger Must Watch Season 6/5 The Door Must Watch Season 6/6 Blood of My Blood Watch if you have time Season 6/7 The Broken Man Season 6/8 No One Must Watch Season 6/9 Battle of the Bastards Must Watch Season 6/10 Winds of Winter Must Watch . -

Uberlândia De De 2011

SERVIÇO PÚBLICO FEDERAL MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE UBERLÂNDIA INSTITUTO DE PSICOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM PSICOLOGIA Juliane de Oliveira Silva Repúdio à feminilidade ou feminilidade como máscara? Um estudo psicanalítico sobre o feminino em Game of Thrones UBERLÂNDIA 2019 Universidade Federal de Uberlândia - Avenida Maranhão, s/n°, Bairro Jardim Umuarama - 38.408-144 - Uberlândia - MG +55 - 34 - 3218-2701 [email protected] http://www.pgpsi.ufu.br SERVIÇO PÚBLICO FEDERAL MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE UBERLÂNDIA INSTITUTO DE PSICOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM PSICOLOGIA Juliane de Oliveira Silva Repúdio à feminilidade ou feminilidade como máscara? Um estudo psicanalítico sobre o feminino em Game of Thrones Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Psicologia - Mestrado, do Instituto de Psicologia da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, como requisito parcial à obtenção do Título de Mestre em Psicologia. Área de Concentração: Psicologia Orientador: Prof. Dr. Luiz Carlos Avelino da Silva UBERLÂNDIA 2019 Universidade Federal de Uberlândia - Avenida Maranhão, s/n°, Bairro Jardim Umuarama - 38.408-144 - Uberlândia - MG +55 - 34 - 3218-2701 [email protected] http://www.pgpsi.ufu.br Ficha Catalográfica Online do Sistema de Bibliotecas da UFU com dados informados pelo(a) próprio(a) autor(a). S586 Silva, Juliane de Oliveira, 1992 2019 Repúdio à feminilidade ou feminilidade como máscara? [recurso eletrônico] : Um estudo psicanalítico sobre o feminino em Game of Thrones / Juliane de Oliveira Silva. - 2019. Orientador: Luiz Carlos Avelino da Silva. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Pós-graduação em Psicologia. Modo de acesso: Internet. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.14393/ufu.di. -

Binge Bootcamp

BINGE BOOTCAMP Kijk als Samwell Rustig aan, elke dag 2 afleveringen Winter is here, Studieboeken aan Houd je strak aan get ready! de kant het kijkschema Seizoen1 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 1 1. Winter is coming Di 12 maart 2. The Kingsroad Wo 13 maart 3. Lord Snow Wo 13 maart 4. Cripples, Bastards, and Do 14 maart Broken Things 5. The Wolf and the Lion Do 14 maart 6. A Golden Crown Vr 15 maart 7. You Win or You Die Vr 15 maart 8. The Pointy End Za 16 maart 9. Baelor Za 16 maart We leren een wijze les: raak niet te gehecht aan personages. 10. Fire and Blood Zo 17 maart In Essos worden wezens geboren waarvan iedereen dacht dat ze waren uitgestorven. En nu zijn ze nog cute! Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 1. The North Remembers Zo 17 maart 2. The Night Lands Ma 18 maart 3. What is Dead May Never Die Ma 18 maart 1 /4 BINGE BOOTCAMP Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 4. Garden of Bones Di 19 maart 5. The Ghost of Harranhal Di 19 maart 6. The Old Gods and the New Wo 20 maart 7. A Man Without Honor Wo 20 maart 8. The Prince of Winterfell Do 21 maart 9. Blackwater Do 21 maart King’s Landing, de hoofdstad van de Seven Kingsdoms, wordt aangevallen. Wat volgt is episch. 10. Valar Morghulis Vr 22 maart Seizoen3 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 3 1. -

Overseas 2017

overSEAS 2017 This thesis was submitted by its author to the School of English and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, in partial ful- filment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. It was found to be among the best theses submitted in 2017, therefore it was decorated with the School’s Outstanding Thesis Award. As such it is published in the form it was submitted in overSEAS 2017 (http://seas3.elte.hu/overseas/2017.html) ALAPSZAKOS SZAKDOLGOZAT Dávid Szonja Anglisztika alapszak Amerikanisztika szakirány 2017 PLEDGE OF SCHOLARLY HONESTY By my signature below, I certify that my ELTE B.A. thesis, entitled Game of Genders – The Portrayal of Female Characters in the Game of Thrones is entirely the result of my own work, and that no degree has previously been conferred upon me for this work. In my thesis I have cited all the sources (printed, electronic or oral) I have used faithfully and have always indicated their origin. The electronic version of my thesis (in PDF format) is a true representation (identical copy) of this printed version. If this pledge is found to be false, I realize that I will be subject to penalties up to and including the forfeiture of the degree earned by my thesis. Date: 2017.April 4. Signed: ........................................................... EÖTVÖS LORÁND TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM Bölcsészettudományi Kar ALAPSZAKOS SZAKDOLGOZAT Game of Genders - A női karakterek jellemfejlődése a Trónok Harca című sorozatban Game of Genders - The Portrayal of Female Characters in the Game of Thrones Témavezető: Készítette: Dr. Hegyi Pál Dávid Szonja adjunktus anglisztika alapszak amerikanisztika szakirány 2017 Abstract Gender inequality still poses a major problem even in the 21th century, the Hollywood film industry is one of the most prominent areas where this imbalance can be observed. -

Confetti, Volume 5, 2019

Éditrices / Editors: Solomiya Ostapyk, Anna Pellerin Petrova Remerciements spéciaux à nos professeurs / Special thanks to our professors: Douglas Clayton, Joerg Esleben, Rebecca Margolis, Cristina Perissinotto, Agatha Schwartz and / et May Telmissany pour leur participation à la réalisation de ce volume / for their work towards producing this volume. TABLE DES MATIÈRES / TABLE OF CONTENTS In the Public Eye – or Ear: Character and Behaviour in Pop Culture Aux yeux – où à l’oreille – du public : La personnalité et le comportement dans la culture populaire The Significance of a Trauma Survivor: The Representation of PTSD in HBO’s Game of Thrones By Kaila Desjardins .................................................................................................................. 6 Artists & Artisans: A Critical Discourse Analysis of SoundCloud Rap By Kareem Khadr ................................................................................................................... 23 Space and Place: Environment as Identity-Forming L’espace et le lieu : L’environnement à l’origine de l’identité Désorienter : Nerval, déçu, repeint l’Orient Par Raymond Auclair ............................................................................................................ 42 The Social and Cultural Impacts of Reducing the Reliance on Diesel in Canada’s Northern Indigenous Communities By Rebecca L. Cook ................................................................................................................ 63 Representing Women: The Making of