Jazz Columns: Kenny Werner: a Musical Expression of Grief — by Lee Mergner — Jazz Articles 10/14/10 6:55 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18Th Annual Illinois State University Jazz Festival School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 3-21-2014 18th Annual Illinois State University Jazz Festival School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "18th Annual Illinois State University Jazz Festival" (2014). School of Music Programs. 378. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/378 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University College of Fine Arts School of Music Presents th 18 Annual Illinois State University Jazz Festival featuring Dave Pietro With ISU Jazz Ensemble I ISU Center for the Performing Arts March 21 and 22, 2014 This is the one hundred and twentieth program of the 2013-2014 season. 18th Annual ISU Jazz Festival Tentative Schedule (please confirm times with the FINAL SCHEDULE upon arrival) FRIDAY, March 21, ISU CPA Concert Hall 1:00 PM Hickory Creek MS Jazz Band I Frankfort, IL 1:25 Hickory Creek MS Jazz Band II Frankfort, IL 1:50 Pekin Community HS Pekin, IL 2:15 H.L. Richards HS Big Band Oak Lawn, IL 2:40 H.L. Richards HS combo Oak Lawn, IL 3:05- 4:05 Dave Pietro Masterclass 4:45 Williamsville HS Williamsville, IL 5:10 Metamora Township HS Big Band Metamora, IL 5:35 Jacksonville High School Jacksonville, IL 6:00 Metamora Township HS Combo Metamora, IL 8:00 CONCERT: 1) ISU Jazz Ensemble II 2) Dave Pietro w/ ISU Jazz Ensemble I SATURDAY, March 22, ISU CPA Concert Hall 11:00 Morton Jr. -

Western Invitational Jazz Festival 2013–14 Season Saturday 15 March 2014 484Th–486Th Concerts Dorothy U

34th Annual Western Invitational Jazz Festival 2013–14 Season Saturday 15 March 2014 484th–486th Concerts Dorothy U. Dalton Center BILLY DREWES, Saxophone, Guest Artist SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Big Bands Combos 8:00 Kalamazoo Central High School 8:20 Byron Center High School Jazz Lab 8:40 West Michigan Home School 8:40 Loy Norrix High School 9:00 Mishawaka High School 9:00 Black River – “Truth” 9:20 Reeths-Puffer High School 9:20 Byron Center I 9:40 Grandwille High School 9:40 West Michigan Home School 10:00 WMU Jazz Lab Band 10:00 Northview 10:30 Byron Center High School Jazz Band 10:30 Community 5 10:50 Black River High School 10:50 Community 4 11:10 Ripon High School 11:10 Grandville 11:30 Comstock Park High School 11:30 Northside 11:50 Mona Shores High School BREAK 12:40 Mona Shores 1:00 Stevenson High School 1:00 Byron Center II 1:20 Northside High School 1:20 Community 3 1:40 East Kentwood High School 1:40 Community 2 2:00 Lincholn Way High School 2:00 Waterford Kettering 2:20 Northview High School 2:20 Stevenson 2:40 Byron Center Jazz Orchestra 2:40 Community 1 3:15 WMU Advanced Jazz Combo (Rehearsal B) 4:00 Clinic with guest artist Billy Drewes and the Western Jazz Quartet (Recital Hall) 5:00 Announcement of Outstanding Band and Combo Awards and Individual Citations BREAK 7:30 Evening Concert featuring an Outstanding Band and Combo from the Festival and Billy Drewes with the WMU Jazz Orchestra If the fire alarm sounds, please exit the building immediately. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Concert: Kenny Werner Trio, Visiting Artists Series 2004-5 Kenny Werner

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-3-2005 Concert: Kenny Werner Trio, Visiting Artists Series 2004-5 Kenny Werner Kenny Werner Trio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Werner, Kenny and Kenny Werner Trio, "Concert: Kenny Werner Trio, Visiting Artists Series 2004-5" (2005). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5082. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5082 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. CHOOLOF VISITING ARTISTS SERIES 2004-5 ( KENNY WERNER 7:00 p.m. Lecture Hockett Family Recital Hall KENNY WERNER TRIO 8:30 p.m. Concert Ford Hall Sunday,April3, 2005 ITHACA - Program To Be Selected From The Following Tunes Peace Pinocchio/Fall All Things You Are Jabali Peace Stella By Starlight Evidence Chach Beat Degeneration Little Blue Man Trio Imitation Yump Guru Voncify the Emulyans Melodies of 2002 ( Beat Degeneration Form and Fantasy Amongkst Sicilienne Nardis Tears In Heaven Dolphin Dance My Funny Valentine Bill Remembered Time Remembered/Lonnies Lament ( Kenny Werner was born on November 19, 1951 in Brooklyn, NY. At the age of eleven, he recorded a single with a fifteen-piece orchestra and appeared on television playing stride piano. He attended the Manhattan School of Music as a concert piano major. In 1970, he transferred to the Berklee School of Music. In 1977, he recorded his first Long Playing album that featured the music of 'ix Beiderbecke, Duke Ellington, James P. -

HANDPICKED July 30-August 4 • Blue Note

WWW.JAZZINSIDEMAGAZINE.COM AUGUST 2013 Interviews Andrew Cyrille David Chesky Satoko Fujii Francisco Mela Dizzy’s Club, August 19 Roy Hargrove Big Band Blue Note, August 20-25 Marcus Strickland EARL Jazz Standard, August 13-14 Comprehensive Directory of NY Club Concert KLUGH & Event Listings HANDPICKED E view Section! July 30-August 4 • Blue Note xpanded CD Re The Jazz Music Dashboard — Smart Listening Experiences www.ConcordMusicGroup.com www.Chesky.com www.WhalingCitySound.com www.SatokoFujii.com The Stone August 20-25 Like Us facebook.com/JazzInsideMedia Follow Us twitter.com/JazzInsideMag Watch Us youtube.com/JazzInsideMedia TJC14_Ad_Jazz Inside.pdf 1 4/26/13 5:31 PM 13TH ANNUAL SAILING OF THE JAZZ CRUISE WHERE EVERY PERFORMANCE IS SPECIAL Ernie Adams Tony Kadleck John Allred Tom Kennedy Shelly Berg Joe LaBarbera MUSIC DIRECTOR Christoph Luty Alonzo Bodden COMEDIAN Dennis Mackrel Randy Brecker Manhattan Transfer Ann Hampton Callaway Marcus Miller Quartet Quartet Bill Charlap Trio Bob Mintzer Clayton Brothers Lewis Nash Trio Quintet Dick Oatts C Freddy Cole Trio M Ken Peplowski Kurt Elling Quartet SHOW HOST Y Robin Eubanks Houston Person CM Quartet John Fedchock MY BIG BAND DIRECTOR John Pizzarelli CY Quartet JAN. 26-FEB. 2 David Finck Gregory Porter Quartet CMY Chuck Findley 2014 K Poncho Sanchez Bruce Forman Arturo Sandoval Nnenna Freelon Trio Gary Smulyan Wycliffe Gordon GOSPEL SHOW HOST Cedar Walton Trio Jimmy Greene Jennifer Wharton Jeff Hamilton Niki Haris Antonio Hart Tamir Hendelman Dick Hyman Tommy Igoe Sextet Sean Jones TO L L -FREE US & C ANADA FT LAUDERDALE • TURKS & CAICOS • SAN JUAN 888.852.9987 ST. -

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

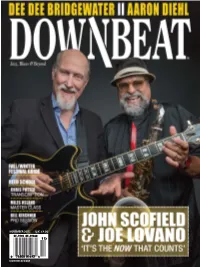

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

Kenny Werner / Jens Søndergaard Duo “A Time for Love“ STUCD 08092

Kenny Werner / Jens Søndergaard Duo “A Time For Love“ STUCD 08092 There were no long, tedious days of rehearsals prior to the session when the Danish saxophonist Jens Søndergaard and American pianist Kenny Werner recorded around 15 ballads from the Great American Songbook. No more than two takes of each tune – if the magic was there, they may as well move on. And the magic most certainly was there, when the two seasoned musicians met at Copenhagen’s Sun Studios; a magic that enabled both players to perform with ease. Jens Søndergaard’s main instrument is the alto, but he also plays baritone and clarinet. He masters his idiom of expression and allows the inspiration of the moment to carry him. Kenny Werner is an awe-inspiring pianist – supersensitive and reflective. He seems to master everything, weaving an extremely beautiful tapestry of notes as a backdrop for the lyrical horn-player. This is how experienced and insightful jazz musicians find each other; this is how the ego is neutralized – a wonderful and elegant recording, lyrical and romantic. Copenhagen was first introduced to Kenny Werner in the ‘80s, when he visited as part of saxophonist Archie Shepp’s quartet. Since then, he returned many times, often to play with Danish drummer Alex Riel’s trio (listen to the Stunt release “Celebration”), but also to see his sax-playing dentist Jens Søndergaard! They played together informally on several occasions, and finally a recording date was arranged. This is the happy result. Kenny Werner (b.1951) is a musician’s musician who impresses equally as a solo pianist, in trio format or with horns. -

We Offer Thanks to the Artists Who've Played the Nighttown Stage

www.nighttowncleveland.com Brendan Ring, Proprietor Jim Wadsworth, JWP Productions, Music Director We offer thanks to the artists who’ve played the Nighttown stage. Aaron Diehl Alex Ligertwood Amina Figarova Anne E. DeChant Aaron Goldberg Alex Skolnick Anat Cohen Annie Raines Aaron Kleinstub Alexis Cole Andrea Beaton Annie Sellick Aaron Weinstein Ali Ryerson Andrea Capozzoli Anthony Molinaro Abalone Dots Alisdair Fraser Andreas Kapsalis Antoine Dunn Abe LaMarca Ahmad Jamal ! Basia ! Benny Golson ! Bob James ! Brooker T. Jones Archie McElrath Brian Auger ! Count Basie Orchestra ! Dick Cavett ! Dick Gregory Adam Makowicz Arnold Lee Esperanza Spaulding ! Hugh Masekela ! Jane Monheit ! J.D. Souther Adam Niewood Jean Luc Ponty ! Jimmy Smith ! Joe Sample ! Joao Donato Arnold McCuller Manhattan TransFer ! Maynard Ferguson ! McCoy Tyner Adrian Legg Mort Sahl ! Peter Yarrow ! Stanley Clarke ! Stevie Wonder Arto Jarvela/Kaivama Toots Thielemans Adrienne Hindmarsh Arturo O’Farrill YellowJackets ! Tommy Tune ! Wynton Marsalis ! Afro Rican Ensemble Allan Harris The Manhattan TransFerAndy Brown Astral Project Ahmad Jamal Allan Vache Andy Frasco Audrey Ryan Airto Moreira Almeda Trio Andy Hunter Avashai Cohen Alash Ensemble Alon Yavnai Andy Narell Avery Sharpe Albare Altan Ann Hampton Callaway Bad Plus Alex Bevan Alvin Frazier Ann Rabson Baldwin Wallace Musical Theater Department Alex Bugnon Amanda Martinez Anne Cochran Balkan Strings Banu Gibson Bob James Buzz Cronquist Christian Howes Barb Jungr Bob Reynolds BW Beatles Christian Scott Barbara Barrett Bobby Broom CaliFornia Guitar Trio Christine Lavin Barbara Knight Bobby Caldwell Carl Cafagna Chuchito Valdes Barbara Rosene Bobby Few Carmen Castaldi Chucho Valdes Baron Browne Bobby Floyd Carol Sudhalter Chuck Loeb Basia Bobby Sanabria Carol Welsman Chuck Redd Battlefield Band Circa 1939 Benny Golson Claudia Acuna Benny Green Claudia Hommel Benny Sharoni Clay Ross Beppe Gambetta Cleveland Hts. -

All-Jazz Real Book

All-Jazz Real Book Title Composer / As Played By Page 2 Degrees East, 3 Degrees West John Lewis 1 2 Down, 1 Across Kenny Garrett 2 A Cor Do Por-Do-Sol Ivan Lins & Celso Viafora 4 Adoracion Eddie Palmieri & Ishmael Quintana 6 Afternoon In Paris John Lewis 11 All Is Quiet Bob Mintzer & Kurt Elling 12 Amanda Duke Pearson 14 Antigua Antonio Carlos Jobim 16 April Mist Tom Harrell 18 At Night Marc Copland 20 At The Close Of The Day Fred Hersch 22 Ayer Y Hoy Dario Eskenazi 24 Azule Serape Victor Feldman 32 Beatrice Sam Rivers 35 The Beauty Of All Things Laurence Hobgood & Kurt Elling 36 Beauty Secrets Kenny Werner 40 Bebe Hermeto Pascoal 42 Being Cool (Aviao) Djavan 44 Beiral Djavan 46 Big J John Scofield 49 Blue Matter John Scofield 50 Blue Seven Sonny Rollins 53 Blues For Pablo Gil Evans 54 Bohemia After Dark Oscar Pettiford 58 Borzeguim Antonio Carlos Jobim 60 Brazilian Suite Michel Petrucciani 68 Broken Wing Richie Beirach 71 Butterfly Dreams Stanley Clarke & Neville Potter 72 Can't Take You Nowhere Tiny Kahn, Al Cohn & Dave Frishberg 74 Cantaloupe Island Herbie Hancock 76 Caprice Eddie Gomez 78 Chitlins Con Carne Kenny Burrell 79 Choro Das Aguas Ivan Lins & Vitor Martins 80 Chris Craft Alan Broadbent 82 Circle Dance Eddie Daniels 84 Congri Rebeca Mauleon 86 Continuacion Orlando "Maraca" Valle 94 Coralie Enrico Pieranunzi 102 Countdown John Coltrane 104 Crazeology Charlie Parker 105 Dance Of Denial Michael Philip Mossman 106 Dare The Moon Darmon Meader, Sara Krieger & Caprice Fox 114 1 All-Jazz Real Book Title Composer / As Played By Page Dark Territory Marc Copland 120 Desalento Chico Buarque 124 Don't Let It Go Vincent Herring 126 Down Miles Davis 128 Dr. -

21. Joe Lovano

21. Joe Lovano o other jazz musician Bailey, Bill Hardman, the from Cleveland has great tenor player Joe N ever achieved the Alexander, and Jim Hall." world-wide acclaim that Because of his family, Tony saxophonist Joe Lovano got decided to remain in in the 1990s and early 2000s. Cleveland. But he was so He was voted "Jazz Artist respected that he often shared of the Year" by DownBeat bandstands with such artists magazine critics and readers as Stan Getz and Flip Phillips in 1995, 1996 and 2001. He when they came to Cleveland. was named "International Drummer Lawrence Artist of the Year" by Jazz "Jacktown" Jackson, who Report magazine in 1995. frequently played with the DownBeat called Cleveland elder Lovano, said, "He native Lovano "the very wasn't as advanced (as Joe epitome of the ' 90s became). He didn't have the professional jazzman." same command of his DownBeat 's Larry instrument, but Tony was a Blumenfeld wrote, "The sheer hell of a saxophone player!" breadth and ambition of When Joey, as he was Lovano's artistic endeavors called, was about 10, his reflect a consistent level of father began giving his son achievement. Lovano raises serious lessons and he began the level of the game and of listening to his father' s those around him." Joe Lovano records , particularl y The DownBeat article saxophonists Sonny Stitt, said Lovano "knows his history, not just the history of John Coltrane and Lester Young, and trumpeter Miles the music, but the value of his personal history." Davis. When Joe was II, his father bought him a King That personal history began in Cleveland where Super 20 tenor saxophone. -

January 2018 Dizzy's Cub Coca-Cola Page 10 Blue Note Page 17

188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 1:49 PM Page 1 The only jazz magazine in NY in print, online THE LATIN SIDE and on apps! OF HOT HOUSE P31 January 2018 www.hothousejazz.com Dizzy's Cub Coca-Cola Page 10 Blue Note Page 17 Jeremy Pelt Roberta Gambarini Tom Harrell Russell Malone Village Vanguard Page 10 Jazz Forum Page 21 Where To Go & Who To See Since 1982 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 4:36 PM Page 2 2 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 1:49 PM Page 3 3 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 1:49 PM Page 4 4 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 1:49 PM Page 5 5 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 5:17 PM Page 6 6 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 5:59 PM Page 7 7 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 1:49 PM Page 8 8 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/21/17 12:05 PM Page 9 9 188536_HH_Jan_0 12/20/17 4:37 PM Page 10 WINNING SPINS By George Kanzler WO TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS trumpet with scintillating bursts of cre- of trumpet players today are that they ativity. Despite the limited instrumenta- Toften double on the fuller, deeper-toned tion, the album is also a tribute to Tom's flugelhorn and that they can usually be fertile playing and consistently engaging found as part of a frontline of two or more composing and arranging. horns in small groups. The two trumpeters Make Noise!, Jeremy Pelt (HighNote), whose new albums comprise this Winning is the latest CD from a trumpeter who Spins do double on flugelhorn, but their emerged three decades after Tom, but CDs are unusual in that both appear as stands firmly in the modern, post-bop the lone horn player with a rhythm sec- mainstream. -

Traditional Jazz Band

JADB bio February 11, 2020 Word count: 1,037 THE JAZZ AMBASSADORS DIXIELAND BAND The Jazz Ambassadors Dixieland Band is an ensemble known for their positive energy and sound musicianship. Inspired mainly by the swinging styles of the great Louis Armstrong and Jack Teagarden, they play a wide variety of traditional jazz, from the classics of the 1920’s and ‘30’s to the early small group swing of the 40’s and 50’s. Comprised of key members of the Jazz Ambassadors, this popular small ensemble is featured at nearly every Jazz Ambassadors concert. The ensemble’s most memorable concerts have been in VA hospitals, Soldiers’ home care facilities, elementary schools, and Independence Day appearances on Good Morning, America! and Fox and Friends. Master Sergeant Bradford Danho, clarinet, is a native of Cranston, Rhode Island and has played tenor saxophone with the Jazz Ambassadors since 2008. MSG Danho earned a Master of Music degree from the University of North Texas, where he played lead alto saxophone with the world-renowned One O'Clock Lab Band and shared the stage with jazz legends such as Phil Woods and Benny Golson. He also received a Bachelor’s degree in Music Education from the Hartt School of the University of Hartford. He has studied saxophone with James Riggs and Michael Menapace and flute with Mary-Karen Clardy. MSG Danho has shared the stage with such artists as Bob Mintzer, Maria Schneider, Pete Christlieb, Bill Holman, Eddie Daniels, and Dick Oatts. He is a two-time alumnus of the Henry Mancini Institute and was a finalist in the 2004 North American Saxophone Alliance Jazz Competition.