“Dictating the Nation: Multilingual Textuality in Theresa Cha's Dictée”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

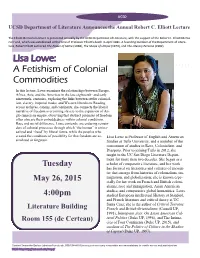

Lisa Lowe: a Fetishism of Colonial Commodities

UCSD UCSD Department of Literature Announces the Annual Robert C. Elliott Lecture The Elliott Memorial Lecture is presented annually by the UCSD Department of Literature, with the support of the Robert C. Elliott Memo- rial Fund, which was established at the time of Professor Elliott's death in April 1981. A founding member of the Department of Litera- ture, Robert Elliott authored The Power of Satire (1968), The Shape of Utopia (1970), and The Literary Persona (1982). Lisa Lowe: A Fetishism of Colonial Commodities In this lecture, Lowe examines the relationships between Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas in the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth- centuries, exploring the links between settler colonial- ism, slavery, imperial trades, and Western liberalism. Reading across archives, canons, and continents, she connects the liberal narrative of freedom overcoming slavery to the expansion of An- glo-American empire, observing that abstract promises of freedom often obscure their embeddedness within colonial conditions. Race and social difference, Lowe contends, are enduring remain- ders of colonial processes through which “the human” is univer- salized and “freed” by liberal forms, while the peoples who created the conditions of possibility for that freedom are as- Lisa Lowe is Professor of English and American similated or forgotten. Studies at Tufts University, and a member of the consortium of studies in Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora. Prior to joining Tufts in 2012, she taught in the UC San Diego Literature Depart- ment for more than two decades. She began as a Tuesday scholar of comparative literature, and her work has focused on literatures and cultures of encoun- ter that emerge from histories of colonialism, im- migration, and globalization; she is known espe- May 26, 2015 cially for her work on French and British coloni- alisms, race and immigration, Asian American studies, and comparative global humanities. -

Critical Terrains

CRITICAL TERRAINS CRITICAL TERRAINS French and British Orientalisms LISA LOWE Cornell University Press Ithaca and London Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1991 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850, or visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 1991 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowe, Lisa. Critical terrains : French and British orientalisms / Lisa Lowe. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8014-2579-0 (cloth) — ISBN-13: 978-0-8014-8195-6 (pbk.) 1. French literature—Oriental infl uences. 2. English literature—Oriental infl uences. 3. French—Travel—Orient—History. 4. British—Travel— Orient—History. 5. Exoticism in literature. 6. Orient in literature. I. Title. PQ143.O75L6 1992 840.9—dc20 91-55058 The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Cover illustration: Ingres, Odalisque with Slave. Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore. for Mei Lee Lowe and Donald M. Lowe Contents Preface ix 1 Discourse and Heterogeneity: Situating Orientalism 1 2 Travel Narratives and Orientalism: Montagu and Montesquieu 30 3 Orient as Woman, Orientalism as Sentimentalism: Flaubert 75 4 Orientalism as Literary Criticism: The Reception of E. -

Spring Newsletter 2013

Spring 2013 Upcoming Events Spring term is always a “Minor Matters –Asian/African, busy time, as projects and Muslim/Christian” plans underway all year April 9 come to fruition in a full calendar of events, “Becoming Jewish-Argentines: including all the year-end Marriage choice, and the celebrations and the construction of a Jewish formal graduation Argentine Identity (1920-1960)” ceremonies in June. April 16 During the winter term, Radical Reading Practices, A History, Languages, Symposium Linguistics, and Literature all successfully recruited April 18-19 new faculty. Look to the fall newsletter for profiles of our six new faculty colleagues. On March 7, Brenda Shaughnessy Poetry Humanities graduate programs collaborated in Reading welcoming prospective grad students to campus to April 25 directly experience the opportunities awaiting them if they decide to pursue their advanced degrees here. Leviathan: Celebrating 40 Years of Jewish Journalism at UCSC Notices about honors and awards—and successful April 28 placements of new PhDs—appear weekly. Look to the Spring Awards ceremony on May 30th for our Helen Diller Family Endowment attempt to collect them all into one celebrative Lecture with Ari Kelman: shout-out to faculty, students, and staff. “Learning to be Jewish” May 8 Upcoming Events I wish you all a successful end of the academic year and best wishes for a pleasant and “Minor Matters –Asian/African, productive summer. Muslim/Christian” April 9 “Becoming Jewish-Argentines: Marriage choice, and the construction of a Jewish Argentine -

Christine “Xine” Yao | 1

Dr. Christine “Xine” Yao | www.christineyao.com 1 CHRISTINE “XINE” YAO DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON GOWER STREET | LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM WC1E 6BT [email protected] | +44 7894 512459 WWW.CHRISTINEYAO.COM | ORCID: 0000-0002-5207-2618 ACADEMIC HISTORY 2018 Lecturer in American Literature to 1900 (UK equivalent to tenure-track Assistant Professor) Department of English Language and Literature, University College London 2016-2018 Postdoctoral Fellow, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Department of English, University of British Columbia 2016 PhD, Department of English, Cornell University Minor Fields: American Studies; Feminism, Gender, and Sexuality Studies th Dissertation: “Feeling Subjects: Science and Law in 19 -Century America” Committee: Shirley Samuels (chair), Eric Cheyfitz, George Hutchinson, Shelley Wong 2013 MA, Department of English, Cornell University 2008 MA, Department of English, Dalhousie University Thesis: “Genre-Splicing: Epic and Novel Hybrids in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman and American Gods,” directed by Jason Haslam 2007 Honours BA, High Distinction, University of Toronto, St. George Campus BOOK PROJECTS The Disaffected: The Cultural Politics of Unfeeling in Nineteenth-Century America. (forthcoming Fall 2021 with Duke University Press. Perverse Modernities series edited by Jack Halberstam and Lisa Lowe) ● Winner of the 2018 Yasuo Sakakibara Essay Prize from the American Studies Association for an excerpt from the main argument and first chapter on Benito Cereno Sex Without Love: Affect, Bodies, and Resistance in Nineteenth-Century Sex Work Narratives. (in progress) PUBLICATIONS Articles Dr. Christine “Xine” Yao | www.christineyao.com 2 “#staywoke: Digital Engagement and Literacies in Anti-Racist Pedagogy.” American Quarterly. -

Palumbo-Liu CV 10 2014 Copy

DAVID PALUMBO-LIU Department of Comparative Literature Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-2031 department: (650) 723-3566 fax: (650) 725-4090 private: (650) 725-4915 e-mail: [email protected] for more information, see: www.palumbo-liu.com Academic Positions 2012- Louise Hewlett Nixon Professor Professor of Comparative Literature and, by courtesy, English, Stanford University. 2001-2012 Professor of Comparative Literature, and, by courtesy, English. 1995-2001 Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, Stanford University. 1994-95 Fellow, Stanford Humanities Center. 1990-94 Assistant Professor, Comparative Literature, Stanford University. 1988-90 Assistant Professor, English and the School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University. 1985-86 Research Fellow, Faculty of Letters, Kyoto University; affiliated with the Research Institute for Humanistic Studies (Fellow, American Council of Learned Societies). Honors Nominated Finalist, Endowed Flexner Lectureship, Bryn Mawr 2008 Offered Jackman Chair in Arts and Humanities, University of Toronto 2007 Administrative Positions 2012- Director, Undergraduate Program in Comparative Studies in Race & Ethnicity 2009-13 Director, Department of Comparative Literature 2009-13 Director, Asian American Studies Program 2009- Executive Committee, Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity 2009- Executive Committee, Division of Literatures, Cultures and Languages 1999-2005- Director of the Program in Modern Thought & Literature, Stanford University 1999-2005, Director, Asian American Studies Program 2006-2007 Director, Program in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity 2005-2006 Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Comparative Literature Education 1988 BA, MA, Ph.D., Comparative Literature (Chinese, French, English), University of California, Berkeley Areas of Interest Asian and Asian Pacific American studies; race, migrancy and ethnicity; cultural studies; comparative literatures; literary theory and criticism; social theory; local/global issues.