Edward Ridley & Sons Department Store Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

151 Canal Street, New York, NY

CHINATOWN NEW YORK NY 151 CANAL STREET AKA 75 BOWERY CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION GROUND FLOOR Northeast corner of Bowery CANAL STREET SPACE 30 FT Ground Floor 2,600 SF Basement 2,600 SF 2,600 SF Sub-Basement 2,600 SF Total 7,800 SF Billboard Sign 400 SF FRONTAGE 30 FT on Canal Street POSSESSION BASEMENT Immediate SITE STATUS Formerly New York Music and Gifts NEIGHBORS 2,600 SF HSBC, First Republic Bank, TD Bank, Chase, AT&T, Citibank, East West Bank, Bank of America, Industrial and Commerce Bank of China, Chinatown Federal Bank, Abacus Federal Savings Bank, Dunkin’ Donuts, Subway and Capital One Bank COMMENTS Best available corner on Bowery in Chinatown Highest concentration of banks within 1/2 mile in North America, SUB-BASEMENT with billions of dollars in bank deposits New long-term stable ownership Space is in vanilla-box condition with an all-glass storefront 2,600 SF Highly visible billboard available above the building offered to the retail tenant at no additional charge Tremendous branding opportunity at the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge with over 75,000 vehicles per day All uses accepted Potential to combine Ground Floor with the Second Floor Ability to make the Basement a legal selling Lower Level 151151 C anCANALal Street STREET151 Canal Street NEW YORKNew Y |o rNYk, NY New York, NY August 2017 August 2017 AREA FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS/BRANCH DEPOSITS SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LUDLOW STREET ESSEX STREET SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LEGEND LUDLOW -

Elizabeth Street Chinatown, Nyc

80 RETAIL FOR LEASE ELIZABETH STREET CHINATOWN, NYC Corner of Elizabeth & Hester Streets APPROXIMATE SIZE Ground Floor: 15,620 SF Selling Lower Level: 12,697 SF Total: 28,317 SF ASKING RENT TERM Upon Request Long Term FRONTAGE POSSESSION 175 FT x 100 FT Arranged COMMENTS • Prime corner retail space, spanning 28,317 SF at the convergence of Chinatown, Little Italy, and the Lower East Side • Current tenant, Hong Kong Supermarket, has established itself as an anchor in the neighborhood and has been operating for 25+ years • Located in close proximity to the Grand Street and Canal Street subway stations, the space is easily accessible from both Manhattan and the outer boroughs • 24/7 foot traffic • All Uses/Logical Divisions Considered • New to Market NEIGHBORS Jing Fong • TD Bank • Shanghai Dumpling • Wyndham Garden Chinatown • Citi Bank • Best Western Bowery • Puglia • Original Vincent’s • Canal Street • Chase Bank • The Original Chinatown Ice Cream Factory TRANSPORTATION JAMES FAMULARO KEVIN BISCONTI JOHN ROESCH President Director Director [email protected] [email protected] 212.468.5962 212.468.5971 All information supplied is from sources deemed reliable and is furnished subject to errors, omissions, modifications, removal of the listing from sale or lease, and to any listing conditions, including the rates and manner of payment of commissions for particular offerings imposed by Meridian Capital Group. This information may include estimates and projections prepared by Meridian Capital Group with respect to future events, and these future events may or may not actually occur. Such estimates and projections reflect various assumptions concerning anticipated results. While Meridian Capital Group believes these assumptions are reasonable, there can be no assurance that any of these estimates and projections will be correct. -

New York's Mulberry Street and the Redefinition of the Italian

FRUNZA, BOGDANA SIMINA., M.S. Streetscape and Ethnicity: New York’s Mulberry Street and the Redefinition of the Italian American Ethnic Identity. (2008) Directed by Prof. Jo R. Leimenstoll. 161 pp. The current research looked at ways in which the built environment of an ethnic enclave contributes to the definition and redefinition of the ethnic identity of its inhabitants. Assuming a dynamic component of the built environment, the study advanced the idea of the streetscape as an active agent of change in the definition and redefinition of ethnic identity. Throughout a century of existence, Little Italy – New York’s most prominent Italian enclave – changed its demographics, appearance and significance; these changes resonated with changes in the ethnic identity of its inhabitants. From its beginnings at the end of the nineteenth century until the present, Little Italy’s Mulberry Street has maintained its privileged status as the core of the enclave, but changed its symbolic role radically. Over three generations of Italian immigrants, Mulberry Street changed its role from a space of trade to a space of leisure, from a place of providing to a place of consuming, and from a social arena to a tourist tract. The photographic analysis employed in this study revealed that changes in the streetscape of Mulberry Street connected with changes in the ethnic identity of its inhabitants, from regional Southern Italian to Italian American. Moreover, the photographic evidence demonstrates the active role of the street in the permanent redefinition of -

161 BOWERYUNIVERSITY PLACE St Union Availablecomm WAVERLY PLACE Christopherpark Public George St Joseph's Theatre Synag St Johns Ch & Sch Acad

ASCAP Bldg Ethical Central Eye Ear Throat 80-88 Lincoln 1900 B'way Culture Presb Ch Hospital Metropolitan Soc & West Opera Center E End Dante Sch A Ch Christ Sci House Plaza YMCA S Geneva Sch Park 2 W 64 E T V D W 63RD STREET W 63RD STREET I E 63RD STREET E 63RD STREET E 63RD STREET R Radisson R New York IV Lowell Society of Barbizon Empire D CENTER DRIVE Damrosch State E Hotel Illustrators Hotel Hotel T Theater Fifth Our Park S Colony Rock Lady of 315 E Ave Synag Club Ch Peace E 62 W W 62ND STREET BROADWAYW 62ND STREET E 62ND STREET E 62ND STREET E 62ND STREET Kincker- Browning Lex bocker Sch United Club Meth Ch Beacon 211 Bible Society Regency W 61 1865 B'way 1114 HS Hotel First W 61ST STREET W 61ST STREET E 61ST STREET E 61ST STREET E 61ST STREET 26 NYIT 330 PS 191 Fordham 16 667 306 W 61 W 61 1855 Trump 660 E 61 University B'way Int'l Mad Mad E 61 Hotel & 655 Christ 770 Heschel 33 W CENTRAL PARK Metropolitan 654 WEST END AVENUE END WEST Tower HS AVENUE COLUMBUS W 60 1841 B'way Club Mad Ch Lex AMSTERDAM AVENUE AMSTERDAM Mad W 60TH STREET E 60TH STREET W 60TH STREET E 60TH STREET Roosevelt E 60TH STREET Prof Harmonie 14 Polo All Child 645 Island Ch St Paul Club E 60 Ralph Mad Saints Sch Apostle 750 Tramway QUEENSBORO BRIDGE 425 Time Warner Lauren Lex Bloomingdale's Ch 635 505 Lighthouse W 59 Center 650 Mad 55 Mad E 59 Park 111 E 59 Bridgemarket CENTRAL PARK S W 59TH STREET 60 Columbus CENTRAL PARK S E 59TH STREET E 59TH STREET E 59TH STREET Circle Ritz- Grand 500 130 330 Carlton 499 110 E 59 E 59 John Jay St Lukes Mandarin Hotel General -

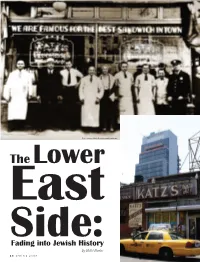

The Lower East Side

Photo courtesy of Katz’s Deli, photographer unknown The Lower East Side: Fading into Jewish History By Hillel Kuttler 26 SPRING 2009 New York — A tan brick wall creased surliness over the abandoned Grand on bialys, but mostly they listen intently. anchors the northern section of the Seward Street Dairy Restaurant. At the corner of Essex and Hester streets, Park apartment complex and its namesake The Rabbi Jacob Joseph yeshiva at one guide displays for her group a black- playground on Manhattan’s Lower East 165–167 Henry Street is now an apartment and-white photograph of the area. It depicts Side. Eight feet up the wall, outside what building, still topped by three engraved the Lower East Side of yore: tenements from once was Sinsheimer’s Café, a plaque com- Stars of David. The Jewish Daily Forward which fire escapes hang, carts of merchan- memorates “the site—60 Essex Street— newspaper no longer is published on East dise, horses, and wall-to-wall people. She where B’nai B’rith, the first national service Broadway, although the Yiddish lettering asks them to consider the present-day vistas organization created in the United States, remains on the original stone structure that with the 110-year-old scene in mind. was founded on October 13, 1843.” housed it—now a condominium. Many The request is eminently doable. Much of Four blocks south, a placard in a Catholic former clothing shops along Orchard Street the tenement stock remains, as do the fairly churchyard at the corner of Rutgers and are now bars and nightclubs. -

Family Tree Maker

Ancestry of William Allan Dart by Judy Boxler Table of Contents Register Report of RICHARD Dart ...................................................................................................................... 3 Register Report of Ami Holt ............................................................................................................................... 15 Register Report of JOHN Adams........................................................................................................................ 17 Register Report of Father Of Ethan Allen........................................................................................................... 19 Register Report of ROBERT Andrews ............................................................................................................... 21 Register Report of THOMAS Axtell................................................................................................................... 23 Register Report of RICHARD Baker.................................................................................................................. 31 Register Report of THOMAS Bayley ................................................................................................................. 33 Register Report of ZACHARY Bicknell............................................................................................................. 43 Register Report of NATHANIEL Billings, Sr. .................................................................................................. -

F. Vehicular Traffic

Chapter 9: Transportation (Vehicular Traffic) F. VEHICULAR TRAFFIC EXISTING CONDITIONS STREET AND ROADWAY NETWORK Traffic conditions in the study area vary in relation to a number of factors—the nature of the street and roadway network, surrounding land uses and the presence of major traffic generators, and the intensity of interaction between autos, taxis, trucks, buses, deliveries, and pedestrians. The study area contains five subareas, or zones—Lower Manhattan, the Lower East Side, East Midtown, the Upper East Side, and East Harlem—and each has different street and roadway characteristics along its length. East Midtown, the Upper East Side, and East Harlem are characterized by a regular street grid, with avenues running north-south and streets running east- west. Each of the major north-south avenues—First, Second, Third, Lexington, Park, Madison, and Fifth Avenues—are major traffic carriers. There is just one limited-access roadway, the FDR Drive, which extends around the eastern edge of the study area from its northern end to its southern end. A general overview of the character of the street and roadway network in each of the five zones is presented below. Lower Manhattan is characterized by an irregular grid pattern south of Canal Street. Except for a few major arterials, most streets within the area are narrow with usually just one "moving" lane. Travel is time-consuming and slow along them. Pedestrian traffic often overflows into the street space, further impeding vehicular traffic flow. Water Street and Broadway are the two key north-south streets in this area, and carry two or more effective travel lanes, yet are often difficult to negotiate due to frequent double-parked truck traffic. -

Zoning Text Amendment (ZR Sections 74-743 and 74-744) 3

UDAAP PROJECT SUMMARY Site BLOCK LOT ADDRESS Site 1 409 56 236 Broome Street Site 2 352 1 80 Essex Street Site 2 352 28 85 Norfolk Street Site 3 346 40 (p/o) 135-147 Delancey Street Site 4 346 40 (p/o) 153-163 Delancey Street Site 5 346 40 (p/o) 394-406 Grand Street Site 6 347 71 178 Broome Street Site 8 354 1 140 Essex Street Site 9 353 44 116 Delancey Street Site 10 354 12 121 Stanton Street 1. Land Use: Publicly-accessible open space, roads, and community facilities. Residential uses - Sites 1 – 10: up to 1,069,867 zoning floor area (zfa) - 900 units; LSGD (Sites 1 – 6) - 800 units. 50% market rate units. 50% affordable units: 10% middle income (approximately 131-165% AMI), 10% moderate income (approximately 60-130% AMI), 20% low income, 10% senior housing. Sufficient residential square footage will be set aside and reserved for residential use in order to develop 900 units. Commercial development: up to 755,468 zfa. If a fee ownership or leasehold interest in a portion of Site 2 (Block 352, Lots 1 and 28) is reacquired by the City for the purpose of the Essex Street Market, the use of said interest pursuant to a second disposition of that portion of Site 2 will be restricted solely to market uses and ancillary uses such as eating establishments. The disposition of Site 9 (Block 353, Lot 44) will be subject to the express covenant and condition that, until a new facility for the Essex Street Market has been developed and is available for use as a market, Site 9 will continue to be restricted to market uses. -

Name Website Address Email Telephone 11R Www

A B C D E F 1 Name Website Address Email Telephone 2 11R www.11rgallery.com 195 Chrystie Street, New York, NY 10002 [email protected] 212 982 1930 Gallery 14th St. Y https://www.14streety.org/ 344 East 14th St, New York, NY 10003 [email protected] 212-780-0800 Community 3 4 A Gathering of the Tribes tribes.org 745 East 6th St Apt.1A, New York, NY 10009 [email protected] 212-777-2038 Cultural 5 ABC No Rio abcnorio.org 156 Rivington Street , New York, NY 10002 [email protected] 212-254-3697 Cultural 6 Abrons Arts Center abronsartscenter.org 456 Grand Street 10002 [email protected] 212-598-0400 Cultural 7 Allied Productions http://alliedproductions.org/ PO Box 20260, New York, NY 10009 [email protected] 212-529-8815 Cultural Alpha Omega Theatrical Dance Company, http://alphaomegadance.org/ 70 East 4th Street, New York, NY 10003 [email protected] Cultural 8 Inc. 9 Amerinda Inc. (American Indian Artists) amerinda.org 288 E. 10th Street New York, NY 10009 [email protected] 212-598-0968 Cultural 10 Anastasia Photo anastasia-photo.com 166 Orchard Street 10002(@ Stanton) [email protected] 212-677-9725 Gallery 11 Angel Orensanz Foundation orensanz.org 172 Norfolk Street, NY, NY 10002 [email protected] 212-529-7194 Cultural 12 Anthology Film Archives anthologyfilmarchives.org 32 2nd Avenue, NY, NY 10003 [email protected] 212-505-5181 Cultural 13 ART Loisaida / Caroline Ratcliffe http://www.artistasdeloisiada.org 608 East 9th St. #15, NYC 10009 [email protected] 212-674-4057 Cultural 14 ARTIFACT http://artifactnyc.net/ 84 Orchard Street [email protected] Gallery 15 Artist Alliance Inc. -

M22 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

M22 bus time schedule & line map M22 Lower East Side - Battery Park City View In Website Mode The M22 bus line (Lower East Side - Battery Park City) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Battery Pk Cty: 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM (2) Lower E. Side Fdr Dr: 12:00 AM - 11:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest M22 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next M22 bus arriving. Direction: Battery Pk Cty M22 bus Time Schedule 22 stops Battery Pk Cty Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 5:00 AM - 11:55 PM Grand St/Fdr Dr 595 Grand Street, Manhattan Tuesday 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM Cherry St/Jackson St Wednesday 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM 32 Jackson St, Manhattan Thursday 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM Jackson St/Madison St Friday 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM 14 Jackson Street, Manhattan Saturday 12:25 AM - 10:00 PM Madison St/Jackson St 371 Madison Street, Manhattan Madison St/Gouverneur St 305 Madison Street, Manhattan M22 bus Info Direction: Battery Pk Cty Madison St/Montgomery St Stops: 22 Madison Street, Manhattan Trip Duration: 28 min Line Summary: Grand St/Fdr Dr, Cherry St/Jackson Madison St/Clinton St St, Jackson St/Madison St, Madison St/Jackson St, 209 Clinton Street, Manhattan Madison St/Gouverneur St, Madison St/Montgomery St, Madison St/Clinton St, Madison St/Jefferson St, Madison St/Jefferson St Madison St/Rutgers St, Madison St/Pike St, E 221 Madison St, Manhattan Broadway/Market St, E Broadway/Catherine St, Worth St/Mott St, Worth St/Centre St, Centre Madison St/Rutgers St St/Chambers St, Chambers -

Chinatown Little Italy Hd Nrn Final

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Chinatown and Little Italy Historic District other names/site number 2. Location Roughly bounded by Baxter St., Centre St., Cleveland Pl. & Lafayette St. to the west; Jersey St. & street & number East Houston to the north; Elizabeth St. to the east; & Worth Street to the south. [ ] not for publication (see Bldg. List in Section 7 for specific addresses) city or town New York [ ] vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10012 & 10013 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements as set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Ottoman Algeria in Western Diplomatic History with Particular Emphasis on Relations with the United States of America, 1776-1816

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE UNIVERSITE MENTOURI, CONSTANTINE _____________ Ottoman Algeria in Western Diplomatic History with Particular Emphasis on Relations with the United States of America, 1776-1816 By Fatima Maameri Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of Languages, University Mentouri, Constantine in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctorat d’Etat Board of Examiners: Supervisor: Dr Brahim Harouni, University of Constantine President: Pr Salah Filali, University of Constantine Member: Pr Omar Assous, University of Guelma Member: Dr Ladi Toulgui, University of Guelma December 2008 DEDICATION To the Memory of my Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Brahim Harouni for his insightful and invaluable remarks as well as his patience which proved to be very decisive for this work. Without his wise advice, unwavering support, and encouragement throughout the two last decades of my research life this humble work would have never been completed. However, this statement is not a way to elude responsibility for the final product. I alone am responsible for any errors or shortcomings that the reader may find. Financial support made the completion of this project easier in many ways. I would like to express my gratitude for Larbi Ben M’Hidi University, OEB with special thanks for Pr Ahmed Bouras and Dr El-Eulmi Laraoui. Dr El-Mekki El-Eulmi proved to be an encyclopedia that was worth referring to whenever others failed. Mr. Aakabi Belkacem is laudable for his logistical help and kindness.