2 Little Things Mean a Lot Odysseus’ Scar and Eurycleia’S Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Cash Box , Music Page 18

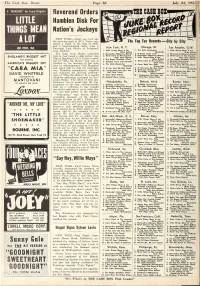

The Cash Box , Music Page 18 A "HIGHLIGHT” For Every Program Reverend Orders LIU1LE Hamblen Disk For THINGS MEAN Nation’s Jockeys NEW YORK—About one week ago Al.OT the morning mail at RCA Victor con- tained a check in the sum of $850. and a heartwarming letter from a York, N. Y. Chicago, III. Los LEO FEIST, INC. Reverend Jack Shuler of Independ- New Angeles, Calif. ence, Kansas. 1. Little Things Mean A lot 1. The Little Shoemaker 1. Little Things Mean A Lot (Kitty Kallen) (Gaylords) (Kitty Kallen! The letter from Shuler explained 2. Hernando's Hideawav (Bleyer) 2. Sh-Boom (Crew Cuts) 2. Hernando's Hideaway (Bleyer; that he had heard a disk jockey spin 3. Three Coins In The Fountain 3. Hernando's Hideaway (Bleyer) 3. Three Coins In The Fountain ENGLAND'S BIGGEST HIT (Four Aces— Sinatra) 4. Little Things Mean A Lot (Four Sinatra) Stuart Hamblen’s RCA Victor record- Aces— \ Fast Becoming 4. The Happy Wanderer (Weir) (Kittv Kallen) 4. The Happy Wanderer (Weir) 5. Three Coins In The Fountain 5. ing of “This Ole House” and was so 5. Sh-Boom (Crew Cuts—Chords) Sh-Boom (Crew-Cuts) (Four Aces) 6. Sway (Dean Martin) AMERICA'S BIGGEST HIT touched by the message in the song 6. The Little Shoemaker 6. Crazy 'Bout You, Baby 7. If You Love Me (Kay Starr) that he communicated with Hamblen (Gaylords) (Crew-Cuts) 8. The Little Shoemaker visit 7. If You love (Kay Starr) 7. If You Love Me (Kay Starr) and asked him to his congrega- Me (Gaylords) "CARA MIA" 8. -

The Million - Seller Records

THE MILLION - SELLER RECORDS A List of Most of The Records Which Have Topped The Miiiion Mark Mercury 1952 Jenkins, Gordon Maybe You’ll Be There Decca 1947 Doggie in the Window 1953 with The Weavers Goodnight, Irene Decca 1950 Changing Partners Mercury Mercury 1954 Jolson, A1 April Sliowers b/w Swanee Decca 1945 Cross Over the Bridge Mercury 1956 California Here I Come b/w Allegheny Moon Rockabye Your Baby Decca 1946 Patience & Prudence Tonight You Belong To Me Liberty 1956 You Made Me Love You b/w Paul, Les & How High The Moon Capitol 1947 Ma Blushin’ Rosie Decca 1946 Mary Ford Mockin’ Bird Hill Capitol 1949 Sonny Boy b/w My Mammy Decca 1946 The World Is Waiting For the Anniversary Song Decca 1946 Sunrise Capitol 1949 Jones, Jimmy Handy Man Cub 1960 Vaya Con Dios Capitol 1953 Good Timin’ Cub 1960 Phillips, Phil Sea Of Love Mercury 1959 Jones, Spike Cocktails For Two Victor 1944 Platters Only You Mercury 1955 1955 All I Want For Christmas Victor 1948 The Great Pretender Mercury Jordan, Louis Choo Cho Ch’Boogie Decca 1946 My Prayer Mercury 1956 Justis, Bill Raunchy Phillips Int 1958 Twilight Time Mercury 1958 Kalin Twins When Decca 1958 Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mercury 1959 Kallen, Kitty Little Things Mean A Lot Decca 1954 Playmates Beep Beep Roulette 1958 King, Pee Wee Slow Poke Victor 1951 Prado, Perez Cherry Pink And Apple Blossom Kingston Trio Tom Dooley Capitol 1958 White Victor 1955 Knight, Evelyn A Little Bird Told Me Decca 1948 Patricia Victor 1958 Kyser, Kay Three Little Fishes Columbia 1941 Preston, Johnny Running Bear Mercury -

Emerging Global Role of Small Lakes and Ponds: Little Things Mean a Lot

Limnetica, 29 (1): x-xx (2008) Limnetica, 29 (1): 9-24 (2010). DOI: 10.23818/limn.29.02 c Asociacio´ n Iberica´ de Limnolog´a, Madrid. Spain. ISSN: 0213-8409 Emerging global role of small lakes and ponds: little things mean a lot John A. Downing∗ Ecology, Evolution & Organismal Biology, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA 2 ∗ Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Received: 6/10/09 Accepted: 18/10/09 ABSTRACT Emerging global role of small lakes and ponds: little things mean a lot Until recently, small continental waters have been completely ignored in virtually all global processes and cycles. This has resulted from the neglect of these systems and processes by ecologists and the assumption that ecosystems with a small areal extent cannot play a major role in global processes. Recent inventories based on modern geographical and mathematical approaches have shown that continental waters occupy nearly twice as much area as was previously believed. Further, these inventories have shown that small lakes and ponds dominate the areal extent of continental waters, correcting a century- long misconception that large lakes are most important. The global importance of any ecosystem type in a process or cycle is the product of the areal extent and the intensity of the process in those ecosystems. Several analyses have shown the disproportionately great intensity of many processes in small aquatic ecosystems, indicating that they play an unexpectedly major role in global cycles. Assessments of the global carbon cycle underscore the need for aquatic scientists to view their work on a global scale in order to respond to the Earth’s most pressing environmental problems. -

Unart Label Discography

Unart Label Discography The Unart label, a subsidiary of the United Artists label, was formed in 1958. It released singles initially, but in 1967 and 1968, it was used as a budget label releasing truncated versions of previously released albums. Unart M20000/S21000 Series: M 20001/S 21001 –Hit Themes from Motion Pictures –Various Artists [1967] Moon River –Ferrante and Teicher/Zorba the Greek –Leroy Holmes/Paris Blues –Louis Armstrong/Guns of Navarone –Al Caiola/Lili Marlene –Ralph Martinie/Hallelujah Trail –Elmer Bernstein/El Cid –Nick Perito/One, Two, Three Waltz –Roger Wayne/Happy Thieves –Nick Perito/It’sa Mad, Mad Mad, Mad, World –Ernest Gold M 20002/S 21002 –George Jones Sings a Book of Memories –George Jones [1967] Book of Memories/Poor Little Rich Boy/I Heard You Crying in Your Sleep/Peace in the Valley/Best Guitar Picker/Sometime I dreamed/There’sNo Justice/A Real Close Friend/Flame in My Heart/The Warm Red Wind M 20003/S 21003 –Warm and Mellow –Al Caiola [1967] Watermelon Man/Alley Cat/Temptation/Feliz Brasilia/Sugar Island/Be Mind Tonight/I Can’tGive You Anything but Love/Under a Blanket of Blue/All of Me/I Can’tStop Loving You M 20004/S 21004 –Piano Artistry of Ferrante and Teicher –Ferrante and Teicher [1967] Be My Love/Song From Moulin Rouge/My Foolish Heart/Lovers By Starlight/Dreams//Dark Eyes/Mona Lisa/The Late Show/Tammy/A Letter To My Secret M 20005/S 21005 - TV’sTeen Star-Patty Duke –Patty Duke [1967] Downtown/Too Young/What the World Needs Now is Love/All I Have to Do is Dream/little Things Mean a Lot//One Kiss Away/Why -

Australian Music Charts – Compiled by Nostalgia Radio

AUSTRALIAN MUSIC CHARTS – COMPILED BY NOSTALGIA RADIO As played on Australian radio stations TOP 60 SONGS 1950-1954 TOP 60 SONGS 1955-1959 1: Too young - Nat King Cole 1: Smoke gets in your eyes - Platters 2: Quicksilver - Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters 2: Just walking in the rain - Johnnie Ray 3: Happy wanderer - Frank Weir 3: Whatever will be, will be (que sera sera) - Doris Day 4: Music music music - Donald Peers 4: Round and round - Perry Como 5: Auf wiedersehen, sweetheart - Vera Lynn 5: Around the world - Bing Crosby 6: Pretend - Nat King Cole 6: Diana - Paul Anka 7: Lavender blue (dilly dilly) - Burl Ives 7: Catch a falling star - Perry Como 8: Goodnight Irene - Gordon Jenkins and the Weavers 8: Tom Dooley - Kingston Trio 9: Because of you - Tony Bennett 9: Joeys song - Bill Haley a/ h Comets 10: A kiss to build a dream on - Louis Armstrong 10: Volare - Domenico Modueno 11: You belong to me - Jo Stafford 11: Hold my hand - Don Cornell 12: Song from Moulin Rouge - Percy Faith 12: Melody of love - Four Aces 13: Mona Lisa - Dennis Day 13: Rock around the clock - Bill Haley and his Comets 14: Bewitched - Gordon Jenkins 14: Yellow rose of Texas - Mitch Miller 15: Slowcoach - Pee Wee King 15: Sixteen tons - Tennessee Ernie Ford 16: Cry - Johnnie Ray 16: Singing the blues - Guy Mitchell 17: Til I waltz again with you - Teresa Brewer 17: April love - Pat Boone 18: Rags to riches - Tony Bennett 18: Purple people eater - Sheb Wooley 19: Little things mean a lot - Kitty Kallen 19: A fool such as I - Elvis Presley 20: “A” you’re adorable - Perry Como a/t Fontaine Sist. -

CB-1960-08-06-OCR-Pa

— — — — MOST PLAYED RECORDS OF THE PAST 13 YEARS^ "^The Top 10 Records of 1947 thru 1959 As Compiled by THE CASH BOX in its Annual Year-End Poll 1947 1951 1955 1. Peg O’ My Heart—The Harmonicats 1. Tennessee Waltz—Patti Page 1. Rock Around The Clock—Bill Haley & Comets 2. Crockett Bill 2. Near You—Francis Craig 2. How High The Moon—Les Paul & Mary Ford Davy — Hayes 3. Cherry Pink And Apple Blossom White 3. Heartaches Ted Weems 3. Too Young Nat “King” Cole — — 10. Perez Prado 4. 4. Anniversary Song—A1 Jolson Be My Love—Mario Lanza 4. Melody Of Love Billy Vaughn 10. — 5. That’s My Desire—Frankie Laine 5. Because Of You—Tony Bennett 5. Yellow Rose Of Texas—Mitch Miller 6. Mamselle—Art Lund 6. On Top Of Old Smoky—Weavers & 6. Ain’t That A Shame—Pat Boone Terry 7. Sincerely—McGuire Sisters 7. Linda—Charlie Spivak Gilkyson 8. Unchained Melody—A1 Hibbler 8. I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now 7. If—Perry Como 9. Crazy Otto—Johnny Maddox Perry Como 8. Sin—Four Aces Mr. Sandman—Chordettes 9. Anniversary Song—Guy Lombardo 9. Come On-A My House—Rosemary Clooney 10. That’s My Desire—Sammy Kaye Mockin’ Bird Hill—Les Paul & Mary Ford 1956 10. 1. Don’t Be Cruel—Elvis Presley 1948 2. The Great Pretender—Platters 1952 3. My Prayer—Platters 10. 10. 4. The Wayward Wind—Gogi Grant 1. My Happiness Jon Sondra Steele — & 5. Whatever Will Be, Will Be—Doris Day 2. Manana—Peggy Lee 1. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

How to Use This Songfinder

as of 3.14.2016 How To Use This Songfinder: We’ve indexed all the songs from 26 volumes of Real Books. Simply find the song title you’d like to play, then cross-reference the numbers in parentheses with the Key. For instance, the song “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive” can be found in both The Real Book Volume III and The Real Vocal Book Volume II. KEY Unless otherwise marked, books are for C instruments. For more product details, please visit www.halleonard.com/realbook. 01. The Real Book – Volume I 10. The Charlie Parker Real Book (The Bird Book)/00240358 C Instruments/00240221 11. The Duke Ellington Real Book/00240235 B Instruments/00240224 Eb Instruments/00240225 12. The Bud Powell Real Book/00240331 BCb Instruments/00240226 13. The Real Christmas Book – 2nd Edition Mini C Instruments/00240292 C Instruments/00240306 Mini B Instruments/00240339 B Instruments/00240345 CD-ROMb C Instruments/00451087 Eb Instruments/00240346 C Instruments with Play-Along Tracks BCb Instruments/00240347 Flash Drive/00110604 14. The Real Rock Book/00240313 02. The Real Book – Volume II 15. The Real Rock Book – Volume II/00240323 C Instruments/00240222 B Instruments/00240227 16. The Real Tab Book – Volume I/00240359 Eb Instruments/00240228 17. The Real Bluegrass Book/00310910 BCb Instruments/00240229 18. The Real Dixieland Book/00240355 Mini C Instruments/00240293 CD-ROM C Instruments/00451088 19. The Real Latin Book/00240348 03. The Real Book – Volume III 20. The Real Worship Book/00240317 C Instruments/00240233 21. The Real Blues Book/00240264 B Instruments/00240284 22. -

Big Band & Swing & Waltz

30s 40s 50s.txt ALPERT, HERB - NEVER ON A SUNDAY ALPERT, HERB - ZORBA THE GREEK AMES BROTHERS - RAG MOP AMES BROTHERS - SENTIMENTAL ME AMES BROTHERS - YOU YOU YOU ANDERSON, LEROY - BLUE TANGO ANDREWS SISTERS - BEAT ME DADDY EIGHT TO THE BAR ANDREWS SISTERS - BEER BARREL POLKA ANDREWS SISTERS - BEI MIR BIST DU SCHON ANDREWS SISTERS - BOOGIE WOOGIE BUGEL BOY ANDREWS SISTERS - DADDY ANDREWS SISTERS - DONT SIT UNDER THE APPLE TREE ANDREWS SISTERS - FERRY BOAT SERENADE ANDREWS SISTERS - HOLD TIGHT (SEAFOOD MAMA) ANDREWS SISTERS - I CAN DREAM CAN'T I ANDREWS SISTERS - OH JOHNNY OH JOHNNY OH ANDREWS SISTERS - OLD PIANO ROLL BLUES ANDREWS SISTERS - PENNSYLVANIA POLKA ANDREWS SISTERS - RUM AND COCA COLA ANDREWS SISTERS - RUM BOOGIE ANDREWS SISTERS - SHOO SHOO BABY ANDREWS SISTERS - THREE LITTLE FISHIES ANDREWS SISTERS & GORDON JENKINS - I WANNA BE LOVED ANTHONY, RAY - DRAGNET ANTHONY, RAY - HOKEY POKEY ARMSTRONG, LOUIS - A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON ARMSTRONG, LOUIS - ALL OF ME ARMSTRONG, LOUIS - HELLO DOLLY ARMSTRONG, LOUIS - JEEPERS CREEPERS ARMSTRONG, LOUIS - STAR DUST ARMSTRONG, LOUIS - WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD ARMSTRONG, LOUIS - YOU RASCAL YOU ASTAIRE, FRED - A FINE ROMANCE ASTAIRE, FRED - CHANGE PARTNERS ASTAIRE, FRED - CHEEK TO CHEEK ASTAIRE, FRED - I'M PUTTING ALL MY EGGS IN ONE BASKET ASTAIRE, FRED - NICE WORK IF YOU CAN GET IT ASTAIRE, FRED - PUTTIN ON THE RITZ ASTAIRE, FRED - THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT ASTAIRE, FRED - THEY CANT TAKE THAT AWAY FROM ME ATKINS, CHET - HOT TODDY AYRES, MITCHELL - MAKE BELIEVE ISLAND BARNETT, CHARLIE - WHERE WAS I BARNETT, CHARLIE - CHEROKEE BARNETT, CHARLIE - POMPTON TURNPIKE BARNETT, CHARLIE - THAT OLD BLACK MAGIC BARTON, EILEEN - IF I KNEW YOU WERE COMING I'D HAVE BAKED A CAKE BAXTER, LES - UNCHAINED MELODY Page 1 30s 40s 50s.txt BAXTER. -

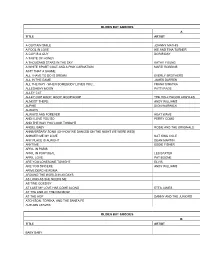

Oldies but Goodies a Title Artist a Certain Smile Johnny Mathis a Fool in Love Ike and Tina Turner a Guy Is a Guy Doris Day a Ta

OLDIES BUT GOODIES A TITLE ARTIST A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS A FOOL IN LOVE IKE AND TINA TURNER A GUY IS A GUY DORIS DAY A TASTE OF HONEY A THOUSAND STARS IN THE SKY KATHY YOUNG A WHITE SPORT COAT AND A PINK CARNATION MARTI ROBBINS AIN'T THAT A SHAME ALL I HAVE TO DO IS DREAM EVERLY BROTHERS ALL IN THE GAME JAMES DARREN ALL THE WAY - WHEN SOMEBODY LOVES YOU… FRANK SINATRA ALLEGHENY MOON PATTI PAGE ALLEY CAT ALLEY OOP BOOP, BOOP, BOOP BOOP THE HOLLYWOOD ARGYLES ALMOST THERE ANDY WILLIAMS ALPHIE DION WARWICK ALWAYS ALWAYS AND FOREVER HEAT WAVE AND I LOVE YOU SO PERRY COMO AND THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT ANGEL BABY ROSIE AND THE ORIGINALS ANNIVERSARY SONG (OH HOW WE DANCED ON THE NIGHT WE WERE WED) ANSWER ME MY LOVE NAT KING COLE ANY PLACE IS ALRIGHT DEAN MARTIN ANYTIME EDDIE FISHER APRIL IN PARIS APRIL IN PORTUGAL LES BAXTER APRIL LOVE PAT BOONE ARE YOU LONESOME TONIGHT ELVIS ARE YOU SINCERE ANDY WILLIAMS ARIVE DERCHE ROMA AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS AS LONG AS SHE NEEDS ME AS TIME GOES BY AT LAST MY LOVE HAS COME ALONG ETTA JAMES AT THE END OF THE RAINBOW AT THE HOP DANNY AND THE JUNIORS ATCHISON, TOPEKA, AND THE SANTA FE AUTUMN LEAVES OLDIES BUT GOODIES B TITLE ARTIST BABY BABY BABY DON'T SAY DON'T ELVIS PRESLEY BABY ELEPHANT WALK BABY I'M YOURS MAMA CASS BAND OF GOLD BARBARA ANN THE BEACH BOYS BECAUSE (YOU'VE COME TO ME) PERRY COMO BECAUSE OF YOU BEWITCHED, BOTHERED AND BEWILDERED BIG JOHN JIMMY DEAN BIG MAN FOUR PREPS BIRD DOG EVERLY BROTHERS BLAME IT ON THE BOSANOVA BLOWIN' IN THE WIND PETER PAUL & MARY BLUE HAWAII ELVIS PRESLEY BLUE