Scottish Overseas Trade, 1275/86-1597

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Queensferry and Inverkeithing (Potentially Vulnerable Area 10/10)

North Queensferry and Inverkeithing (Potentially Vulnerable Area 10/10) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Forth Estuary Fife Council South Fife coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impacts flooding of Summary At risk of flooding • 40 residential properties • 30 non-residential properties • £590,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning -

View Preliminary Assessment Report Appendix C

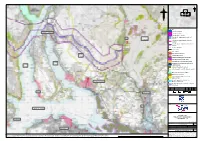

N N ? ? d c b a Legend Corrid or 4 e xte nts GARELOCHHEAD Corrid or 5 e xte nts Corrid or 4 & 5 e xte nts Corrid or 4 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of A82 LOCH c orrid or LOMOND Corrid or 5 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of c orrid or Corrid or 4 & 5 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of c orrid or G A L iste d Build ing Gre at T rails Core Paths Sc he d ule d Monum e nt GLEN Conse rvation Are a FRUIN Gard e n and De signe d L and sc ap e Sp e c ial Prote c tion Are a (SPA) Sp e c ial Are a of Conse rvation (SAC) GARE LOCH W e tland s of Inte rnational Im p ortanc e LOCH (Ram sar Site s) LONG Anc ie nt W ood land Inve ntory Site of Sp e c ial Sc ie ntific Inte re st (SSSI) Marine Prote c te d Are a (MPA) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! National Sc e nic Are a L oc h L om ond and the T rossac hs National Park Flood Map p ing Coastal Exte nts – HELENSBURGH Me d ium L ike lihood Flood Map p ing Rive r Exte nts – Me d ium L ike lihood P01 12/02/2021 For Information TS RC SB DR Re v. Re v. Date Purp ose of re vision Orig/Dwn Che c kd Re v'd Ap p rv'd COVE BALLOCH Clie nt Proje c t A82 FIRTH OF CLYDE Drawing title FIGU RE C.2A PREL IMINARY ASSESSMENT CORRIDORS 4, 5 DUNOON She e t 01 of 04 Drawing Status Suitab ility FOR INFORMATION S2 Sc ale 1:75,000 @ A3 DO NOT SCALE Jac ob s No. -

Historic Arts and Crafts House with Separate Cottage and Views Over the Gare Loch

Historic Arts and Crafts house with separate cottage and views over the Gare Loch Ferry Inn, Rosneath, By Helensburgh, G84 0RS Lower ground floor: Sitting room, bedroom/gym, WC. Ground floor: Reception hall, drawing room, dining room, kitchen, study, morning room, pantry First floor: Principal bedroom with en suite bathroom, 3 further bedrooms, 2 further bathrooms. Ferry Inn Cottage: Detached cottage with living room/bedroom/bedroom, kitchen and shower room Garden & Grounds of around 4 acres. Local Information and both local authority and Ferry Inn is set in around 4 acres private schools. of its own grounds on the Rosneath Peninsula. The grounds The accessibility of the Rosneath form the corner of the promontory Peninsula has been greatly on the edge of Rosneath which improved by the opening of the juts out into the sea loch. There new Ministry of Defence road are magnificent views from the over the hills to Loch Lomond. house over the loch and to the The journey time to Loch marina at Rhu on the opposite. Lomond, the Erskine Bridge and Glasgow Airport has been The Rosneath Peninsula lies to significantly reduced by the new the north of the Firth of Clyde. road which bypasses Shandon, The peninsula is reached by the Rhu and Helensburgh on the road from Garelochhead in its A814 on the other side of the neck to the north. The peninsula loch. is bounded by Loch Long to the northwest, Gare Loch to the east About this property and the Firth of Clyde to the south The original Ferry Inn stood next and is connected to the mainland to the main jetty for the ferry by a narrow isthmus at its which ran between Rosneath and northern end. -

Heartlands of Fife Visitor Guide

Visitor Guide Heartlands of Fife Heartlands of Fife 1 The Heartlands of Fife stretches from the award-winning beaches of the Firth of Forth to the panoramic Lomond Hills. Its captivating mix of bustling modern towns, peaceful villages and quiet countryside combine with a proud history, exciting events and a lively community spirit to make the Heartlands of Fife unique, appealing and authentically Scottish. Within easy reach of the home of golf at St Andrews, the fishing villages of the East Neuk and Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital city, the Heartlands of Fife has great connections and is an ideal base for a short break or a relaxing holiday. Come and explore our stunning coastline, rolling hills and pretty villages. Surprise yourself with our fascinating wildlife and adrenalin-packed outdoor activities. Relax in our theatres, art galleries and music venues. Also don’t forget to savour our rich natural larder. In the Heartlands of Fife you’ll find a warm welcome and all you could want for a memorable visit that will leave you eager to come back and enjoy more. And you never know, you may even lose your heart! Contents Our Towns & Villages 3 The Great Outdoors 7 Golf Excellence 18 Sporting Fun 19 History & Heritage 21 Culture 24 Innovation & Enlightenment 26 Family Days Out 27 Shopping2 Kirkcaldy & Mid Fife 28 Food & Drink 29 Events & Festivals 30 Travel & Accommodation 32 Visitor Information 33 Discovering Fife 34 welcometofife.com Burntisland Set on a wide, sweeping bay, Burntisland is noted for its Regency terraces and A-listed buildings which can be explored on a Burntisland Heritage Trust guided tour. -

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

Whithorn Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Dumfries and Galloway Council LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2 Whithorn Conservation Area Character Appraisal Draft Supplementary Guidance - January 2018 draft www.dumgal.gov.uk draft This conservation area character appraisal was first adopted as supplementary planning guidance to the Wigtown Local Plan. That plan has been replaced by the Local Development Plan (LDP) which is reviewed every 5 years. The conservation area character appraisal is considered by the Council to remain relevant and so will be readopted as Supplementary Guidance to LDP2. Policy HE2: Conservation Areas ties the conservation area character appraisal to LDP2. The policy reinforces the importance and value of conservation area character appraisal as the policy states that “The Council will support development proposals within or adjacent to a conservation area that preserves or enhances the character and appearance of the area and is consistent with any relevant conservation area appraisal and management plan.” draft Whithorn Conservation Area Appraisal Contents Whithorn Conservation Area Character Appraisal .......................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 Background ...........................................................................................................................3 The Conservation Area .........................................................................................................3 The Character Appraisal .......................................................................................................3 -

A4 Paper 12 Pitch with Para Styles

REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE ACT 1983 NOTICE OF CHANGES OF POLLING PLACES within Fife’s Scottish Parliamentary Constituencies Fife Council has decided, with immediate effect to implement the undernoted changes affecting polling places for the Scottish Parliamentary Election on 6th May 2021. The premises detailed in Column 2 of the undernoted Schedule will cease to be used as a polling place for the polling district detailed in Column 1, with the new polling place for the polling district being the premises detailed in Column 3. Explanatory remarks are contained in Column 4. 1 2 3 4 POLLING PREVIOUS POLLING NEW POLLING REMARKS DISTRICT PLACE PLACE Milesmark Primary Limelight Studio, Blackburn 020BAA - School, Regular venue Avenue, Milesmark and Rumblingwell, unsuitable for this Parkneuk, Dunfermline Parkneuk Dunfermline, KY12 election KY12 9BQ 9AT Mclean Primary Baldridgeburn Community School, Regular venue 021BAB - Leisure Centre, Baldridgeburn, unavailable for this Baldridgeburn Baldridgeburn, Dunfermline Dunfermline KY12 election KY12 9EH 9EE Dell Farquharson St Leonard’s Primary 041CAB - Regular venue Community Leisure Centre, School, St Leonards Dunfermline unavailable for this Nethertown Broad Street, Street, Dunfermline Central No. 1 election Dunfermline KY12 7DS KY11 3AL Pittencrieff Primary Education Resource And 043CAD - School, Dewar St, Regular venue Training Centre, Maitland Dunfermline Crossford, unsuitable for this Street, Dunfermline KY12 West Dunfermline KY12 election 8AF 8AB John Marshall Community Pitreavie Primary Regular -

National Developments – Response Form

OFFICIAL Planning for Scotland in 2050 National Planning Framework 4 National Developments – Response Form Please use the table below to let us know about projects you think may be suitable for national development status. You can also tell us your views on the existing national developments in National Planning Framework 3, referencing their name and number, and providing reasons as to why they should maintain their status. Please use a separate table for each project or development. Please fill in a Respondent Information Form and return it with this form to [email protected]. Name of proposed national South West Scotland Coast Path development Brief description of proposed To establish a continuous 500km coast path from the national development England/ Scotland border to Cairnryan. It will create a new world-class outdoor and environmental tourism offer by investing in the natural capital and green infrastructure of Dumfries and Galloway and promote collaboration between cross border local authorities and strategic partners. Location of proposed national Connecting the Cumbrian section of the England development (information in a Coast Path continuing along the Dumfries and GIS format is welcome if Galloway coastline to Ayrshire. See attached plans. available) What part or parts of the Landowner negotiations for the identified gaps in the development requires planning route and creation of new core path designations and permission or other consent? statutory approvals. When would the development 2030 subject to resources and funding be complete or operational? Is the development already Recognised within the Core path plan and the D&G formally recognised – for LDP. The first phase was recognised in the NPF3, example identified in a and is now under construction. -

Flood Risk Management Strategy Solway Local Plan District Section 3

Flood Risk Management Strategy Solway Local Plan District This section provides supplementary information on the characteristics and impacts of river, coastal and surface water flooding. Future impacts due to climate change, the potential for natural flood management and links to river basin management are also described within these chapters. Detailed information about the objectives and actions to manage flooding are provided in Section 2. Section 3: Supporting information 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 31 1 3.2 River flooding ......................................................................................... 31 2 • Esk (Dumfriesshire) catchment group .............................................. 31 3 • Annan catchment group ................................................................... 32 1 • Nith catchment group ....................................................................... 32 7 • Dee (Galloway) catchment group ..................................................... 33 5 • Cree catchment group ...................................................................... 34 2 3.3 Coastal flooding ...................................................................................... 349 3.4 Surface water flooding ............................................................................ 359 Solway Local Plan District Section 3 310 3.1 Introduction In the Solway Local Plan District, river flooding is reported across five distinct river catchments. -

The Opening of the Atlantic World: England's

THE OPENING OF THE ATLANTIC WORLD: ENGLAND’S TRANSATLANTIC INTERESTS DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII By LYDIA TOWNS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May, 2019 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Imre Demhardt, Supervising Professor John Garrigus Kathryne Beebe Alan Gallay ABSTRACT THE OPENING OF THE ATLANTIC WORLD: ENGLAND’S TRANSATLANTIC INTERESTS DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII Lydia Towns, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2019 Supervising Professor: Imre Demhardt This dissertation explores the birth of the English Atlantic by looking at English activities and discussions of the Atlantic world from roughly 1481-1560. Rather than being disinterested in exploration during the reign of Henry VIII, this dissertation proves that the English were aware of what was happening in the Atlantic world through the transnational flow of information, imagined the potentials of the New World for both trade and colonization, and actively participated in the opening of transatlantic trade through transnational networks. To do this, the entirety of the Atlantic, all four continents, are considered and the English activity there analyzed. This dissertation uses a variety of methods, examining cartographic and literary interpretations and representations of the New World, familial ties, merchant networks, voyages of exploration and political and diplomatic material to explore my subject across the social strata of England, giving equal weight to common merchants’ and scholars’ perceptions of the Atlantic as I do to Henry VIII’s court. Through these varied methods, this dissertation proves that the creation of the British Atlantic was not state sponsored, like the Spanish Atlantic, but a transnational space inhabited and expanded by merchants, adventurers and the scholars who created imagined spaces for the English. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

![The Titular Barony of Clavering [Microform] : Its Origin In, and Right Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7215/the-titular-barony-of-clavering-microform-its-origin-in-and-right-of-1567215.webp)

The Titular Barony of Clavering [Microform] : Its Origin In, and Right Of

t4S°l '\%°\\^ FOL ' "; SfißwfN*W^^Hoiise ofClavering, "" ¦>|^-S^itiieMicated and illustrated • < fix)mthe Fublic Records, '. Lord 'iif"War|twQrth. of Clavering. The Baronial Seal of Robert fitz-Roger, Lord of Warkworth and Clavering : • v (affixed to a Deed between 1195-1208). London: Privately printed 1891. e ¦>! 12?: SOUTH VIEW OF AXWELL PARK, IN THE COUNTY OF DURHAM Tim- Seat of Sir Henry Anglistics ClaveHng, Baronet. The Titular oarony of C^layering. Its Origin in, and Right ofInheritance by, the Norman House of Clavering, authenticated and illustrated from the Public Records n j Lord Lord of Warkworth of Clavering The Baronial Seal of Robert fitz-Roger, Lord of Warkworth and Clavering : (affixed to a Deed between 1195-1208). London: Privately printed. 1891. ,*\ < T BEGAN gradually to perceive this immense fact, which Ireally advise every one of you who read history to look out for, if you have not already found it. It was that the Kings of England, all the way from the Norman Conquest down to the times of Charles 1., had actually, in a good degree, so far as they knew, been in the habit of appointing as Peers those who deserved to be appointed. In general Iperceived those Peers of theirs were all Royal men of a sort, withminds fullof justice, valour and humanity, and all kinds of qualities that men ought to have who rule over others. And then their genealogy, the kind of sons and descendants they had, this also was remarkable : for there is a great deal more in genealogy than is generally believed at present.' — ' Carlyle, Inaugural Address at Edinburgh? 1866.