The Fruits and Nuts of the Unicorn Tapestries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon and the Phoenix Teacher's Notes.Indd

Usborne English The Dragon and the Phoenix • Teacher’s notes Author: traditi onal, retold by Lesley Sims Reader level: Elementary Word count: 235 Lexile level: 350L Text type: Folk tale from China About the story A dragon and a phoenix live on opposite sides of a magic river. One day they meet on an island and discover a shiny pebble. The dragon washes it and the phoenix polishes it unti l it becomes a pearl. Its brilliant light att racts the att enti on of the Queen of Heaven, and that night she sends a guard to steal it while the dragon and phoenix are sleeping. The next morning, the dragon and phoenix search everywhere and eventually see their pearl shining in the sky. They fl y up to retrieve it, but the pearl falls down and becomes a lake on the ground below. The dragon and the phoenix lie down beside the lake, and are sti ll there today in the guise of Dragon Mountain and Phoenix Mountain. The story is based on The Bright Pearl, a Chinese folk tale. Chinese dragons are typically depicted without wings (although they are able to fl y), and are associated with water and wisdom. Chinese phoenixes are immortal, and do not need to die and then be reborn. They are associated with loyalty and honesty. The dragon and phoenix are oft en linked to the male yin and female yang qualiti es, and in the past, a Chinese emperor’s robes would typically be embroidered with dragons and an empress’s with phoenixes. -

With Pauline Geneteau Bring You the Paris Forager’S Tour 21-25 October 2019

ForageGoes to France 21-25 OCT 2019 ‘Forage by Lisa Mattock’ and ‘Stitching Up Paris’ with Pauline Geneteau bring you the Paris Forager’s Tour 21-25 October 2019 This small group tour explores the specialist ateliers and stores not on the “normal” tourist track. If you’re a passionate devotee of all things French; food, shopping, art and of course vintage fabrics and notions, then this is the tour for you! Join us for five fabulous days in Paris, Then in the afternoons we will enjoy a personally accompanied by Lisa Mattock private tour of a museum or gallery with of ‘Forage by Lisa Mattock’ and Pauline exhibits pertaining to our love of textiles. Geneteau of ‘Stitching Up Paris’. Numbers are limited to just 10 to make sure We’ll find ribbons, fabrics, haberdashery, and Pauline and Lisa can spend time with all of notions. Mais oui, we will of course also have you and we are able to thoroughly enjoy all a few opportunities for a good “forage” at the beautiful little stores and stalls we’ll visit several delightful brocantes and specialist together. markets. We will also visit specific galleries Formidable!! We can’t wait to share with you and museums dedicated to textiles and the some of our Parisian textile/vintage bucket textile arts. list finds…all I can say is make sure you There will be an adventure each morning bring a big bag, comfortable shoes and an as Pauline takes us to those special places appetite for good food, good fun and great only a local can know, followed by lunch at a Foraging. -

Curiosity Killed the Bird: Arbitrary Hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia

Cotinga30-080617:Cotinga 6/17/2008 8:11 AM Page 12 Cotinga 30 Curiosity killed the bird: arbitrary hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja on an agricultural frontier in southern Brazilian Amazonia Cristiano Trapé Trinca, Stephen F. Ferrari and Alexander C. Lees Received 11 December 2006; final revision accepted 4 October 2007 Cotinga 30 (2008): 12–15 Durante pesquisas ecológicas na fronteira agrícola do norte do Mato Grosso, foram registrados vários casos de abate de harpias Harpia harpyja por caçadores locais, motivados por simples curiosidade ou sua intolerância ao suposto perigo para suas criações domésticas. A caça arbitrária de harpias não parece ser muito freqüente, mas pode ter um impacto relativamente grande sobre as populações locais, considerando sua baixa densidade, e também para o ecossistema, por causa do papel ecológico da espécie, como um predador de topo. Entre as possíveis estratégias mitigadoras, sugere-se utilizar a harpia como espécie bandeira para o desenvolvimento de programas de conservação na região. With adult female body weights of up to 10 kg, The study was conducted in the municipalities Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja (Fig. 1) are the New of Alta Floresta (09º53’S 56º28’W) and Nova World’s largest raptors, and occur in tropical forests Bandeirantes (09º11’S 61º57’W), in northern Mato from Middle America to northern Argentina4,14,17,22. Grosso, Brazil. Both are typical Amazonian They are relatively sensitive to anthropogenic frontier towns, characterised by immigration from disturbance and are among the first species to southern and eastern Brazil, and ongoing disappear from areas colonised by humans. fragmentation of the original forest cover. -

Download Download

Phytopoetics: Upending the Passive Paradigm with Vegetal Violence and Eroticism Joela Jacobs University of Arizona [email protected] Abstract This article develops the notion of phytopoetics, which describes the role of plant agency in literary creations and the cultural imaginary. In order to show how plants prompt poetic productions, the article engages with narratives by modernist German authors Oskar Panizza, Hanns Heinz Ewers, and Alfred Döblin that feature vegetal eroticism and violence. By close reading these texts and their contexts, the article maps the role of plant agency in the co-constitution of a cultural imaginary of the vegetal that results in literary works as well as societal consequences. In this article, I propose the notion of phytopoetics (phyto = relating to or derived from plants, and poiesis = creative production or making), parallel to the concept of zoopoetics.1 Just as zoopoetics describes the role of animals in the creation of texts and language, phytopoetics entails both a poetic engagement with plants in literature and moments in which plants take on literary or cultural agency themselves (see Moe’s [2014] emphasis on agency in zoopoetics, and Marder, 2018). In this understanding, phytopoetics encompasses instances in which plants participate in the production of texts as “material-semiotic nodes or knots” (Haraway, 2008, p. 4) that are neither just metaphor, nor just plant (see Driscoll & Hoffmann, 2018, p. 4 and pp. 6-7). Such phytopoetic effects manifest in the cultural imagination more broadly.2 While most phytopoetic texts are literary, plant behavior has also prompted other kinds of writing, such as scientific or legal Joela Jacobs (2019). -

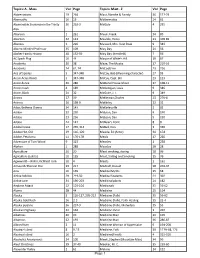

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Download The

1 Studies in Material Thinking, http://www.materialthinking.org Vol. 4 (September 2010), ISSN 1177-6234, AUT University Copyright © Studies in Material Thinking and the author. Cresside Collette Tutor in Tapestry Weaving and Drawing School of Fashion and Textiles RMIT University [email protected] Abstract Since Mediaeval times drawing has been the foundation for and the integrated content of woven tapestry. This paper traces the evolution of a rich, colourful, tactile medium in response to the drawn image, the shift in importance of the weaver as artist within the process, and the emergence of Tapestry as a Contemporary art form in its own right. Keywords Drawing, Tapestry, Cartoon, Artist, Weaver. “Found in Translation – the transformative role of Drawing in the realisation of Tapestry.” Introduction A bold definition of tapestry is that it is a woven work of art. It carries an image, made possible by virtue of what is known as discontinuous weft, i.e. the weft is built up in small shapes rather than running in continuous rows across the warp. The structure of the material comprises warp (vertical) and weft (horizontal) threads. Hand woven on a loom, the weft yarn generally covers the warp, resulting in a weft - faced fabric. The design, which is woven into the fabric, forms an integral part of the textile as the artist/weaver constructs the image and surface simultaneously. Of all the textile arts, tapestry is the medium that finds its form and expression most directly in the drawn line. Drawing is the thread, both literally and metaphorically, that enables the existence of woven tapestry and it has played both a supporting and a didactic role in the realisation of this image - based form. -

2015, L: 189-200 Grădina Botanică “Alexandru Borza” Cluj-Napoca

Contribuţii Botanice – 2015, L: 189-200 Grădina Botanică “Alexandru Borza” Cluj-Napoca THE SYMBOLISM OF GARDEN AND ORCHARD PLANTS AND THEIR REPRESENTATION IN PAINTINGS (I) Camelia Paula FĂRCAŞ1, Vasile CRISTEA2, Sorina FĂRCAŞ3, Tudor Mihai URSU3, Anamaria ROMAN3 1.University of Art and Design, Faculty of Visual Arts, Painting Department, 31 Piaţa Unirii, RO-400098 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2.Babeş-Bolyai University, Department of Taxonomy and Ecology, “Al. Borza”Botanical Garden, 42 Republicii Street RO-400015 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 3.Institute of Biological Research, Branch of the National Institute of Research and Development for Biological Sciences, 48 Republicii Street, RO-400015 Cluj-Napoca, Romania e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Plant symbols are a part of the cultural treasure of humanity, whether we consider the archaic secular traditions or religion, heraldry etc., throughout history until the present day. To flowers, in particular, there have been attributed particular meanings over thousands of years. Every art form has involved flower symbols at some point, but in painting they have an outstanding presence. Early paintings are rich in philosophical and Christian plant symbolism, while 18th–20th century art movements have added new meanings to vegetal-floral symbolism, through the personal perspective of various artists in depicting plant symbols. This paper focuses on the analysis of the ancient plant significance of the heathen traditions and superstitions but also on their religious sense, throughout the ages and cultures. Emphasis has been placed on plants that were illustrated preferentially by painters in their works on gardens and orchards. Keywords: Plant symbolism, paintings, gardens, orchards. Introduction Plant symbols comprise a code of great richness and variety in the cultural thesaurus of humanity. -

Research Article WILDMEN in MYANMAR

The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 4:53-66 (2015) Research Article WILDMEN IN MYANMAR: A COMPENDIUM OF PUBLISHED ACCOUNTS AND REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE Steven G. Platt1, Thomas R. Rainwater2* 1 Wildlife Conservation Society-Myanmar Program, Office Block C-1, Aye Yeik Mon 1st Street, Hlaing Township, Yangon, Myanmar 2 Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science, Clemson University, P.O. Box 596, Georgetown, SC 29442, USA ABSTRACT. In contrast to other countries in Asia, little is known concerning the possible occurrence of undescribed Hominoidea (i.e., wildmen) in Myanmar (Burma). We here present six accounts from Myanmar describing wildmen or their sign published between 1910 and 1972; three of these reports antedate popularization of wildmen (e.g., yeti and sasquatch) in the global media. Most reports emanate from mountainous regions of northern Myanmar (primarily Kachin State) where wildmen appear to inhabit montane forests. Wildman tracks are described as superficially similar to human (Homo sapiens) footprints, and about the same size to almost twice the size of human tracks. Presumptive pressure ridges were described in one set of wildman tracks. Accounts suggest wildmen are bipedal, 120-245 cm in height, and covered in longish pale to orange-red hair with a head-neck ruff. Wildmen are said to utter distinctive vocalizations, emit strong odors, and sometimes behave aggressively towards humans. Published accounts of wildmen in Myanmar are largely based on narratives provided by indigenous informants. We found nothing to indicate informants were attempting to beguile investigators, and consider it unlikely that wildmen might be confused with other large mammals native to the region. -

Dragons and Serpents in JK Rowling's <I>Harry Potter</I> Series

Volume 27 Number 1 Article 6 10-15-2008 Dragons and Serpents in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter Series: Are They Evil? Lauren Berman University of Haifa, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Berman, Lauren (2008) "Dragons and Serpents in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter Series: Are They Evil?," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 27 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol27/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Investigates the role and symbolism of dragons and serpents in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, with side excursions into Lewis and Tolkien for their takes on the topic. Concludes that dragons are morally neutral in her world, while serpents generally represent or are allied with evil. -

Feral Swine Disease Control in China

2014 International Workshop on Feral Swine Disease and Risk Management By Hongxuan He Feral swine diseases prevention and control in China HONGXUAN HE, PH D PROFESSOR OF INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY, CHINESE ACADEMY OF SCIENCES EXECUTIVE DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL RESEARCH CENTER FOR WILDLIFE DISEASES COORDINATOR OF ASIA PACIFIC NETWORK OF WILDLIFE BORNE DISEASES CONTENTS · Feral swine in China · Diseases of feral swine · Prevention and control strategies · Influenza in China Feral swine in China 4 Scientific Classification Scientific name: Sus scrofa Linnaeus Common name: Wild boar, wild hog, feral swine, feral pig, feral hog, Old World swine, razorback, Eurasian wild boar, Russian wild boar Feral swine is one of the most widespread group of mammals, which can be found on every continent expect Antarctica. World distribution of feral swine Reconstructed range of feral swine (green) and introduced populations (blue). Not shown are smaller introduced populations in the Caribbean, New Zealand, sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere. Species of feral swine Now ,there are 4 genera and 16 species recorded in the world today. Western Indian Eastern Indonesian genus genus genus genus Sus scrofa scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa davidi sibiricus vittatus meridionalis Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa algira cristatus ussuricus Sus scrofa Attila Sus scrofa Sus scrofa leucomystax nigripes Sus scrofa Sus scrofa riukiuanus libycus Sus scrofa Sus scrofa majori taivanus Sus scrofa moupinensis Feral swine in China Feral swine has a long history in China. About 10,000 years ago, Chinese began to domesticate feral swine. Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China oracle bone inscriptions of “猪” in Different font of “猪” Shang Dynasty Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China The carving of pig in Han Dynasty Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China In ancient time, people domesticated pig in “Zhu juan”. -

Image and Meaning in the Floral Borders of the Hours of Catherine of Cleves Elizabeth R

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1987 Image and Meaning in the Floral Borders of the Hours of Catherine of Cleves Elizabeth R. Schaeffer Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Art at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Schaeffer, Elizabeth R., "Image and Meaning in the Floral Borders of the Hours of Catherine of Cleves" (1987). Masters Theses. 1271. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1271 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. *****US Copyright Notice***** No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. The user should review the copyright notice on the following scanned image(s) contained in the original work from which this electronic copy was made. Section 108: United States Copyright Law The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that use may be liable for copyright infringement. -

Unicorn Tapestries, Horned Animals, and Prion Disease Polyxeni Potter

ABOUT THE COVER South Netherlandish, The Unicorn Is Found, from Hunt of the Unicorn (1495–1505) Wool warp, wool, silk, silver and gilt wefts, 368 cm x 379 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937 Unicorn Tapestries, Horned Animals, and Prion Disease Polyxeni Potter “The written text is a recent form of textile, ancillary to luxury; and a desire to communicate, shown in banners, ini- those primary texts ‘told’ or ‘tooled’ in cloth” (1). tials, and other messages encrypted on the scenes. Thousands of years before humans could write, they could The Unicorn Is Found, on this month’s cover of weave, turning cloth into a commodity, symbol of wealth, Emerging Infectious Diseases, is one of seven famed tap- and decorative art. In many cultures, weaving has become estries depicting the Hunt of the Unicorn. The works are a common linguistic metaphor as “weave” is used broadly housed at The Cloisters, a part of the Metropolitan to mean “create.” A weaver “not only fashions textiles but Museum of Art, New York, designed specifically to evoke can, with the same verb, contrive texts” (2). the context in which these and other medieval artifacts Textiles, which date back to the Neolithic and Bronze were created (6). The brilliant descriptions in these tapes- Ages, have strong egalitarian roots and an ancient connec- tries of exotic plants and animals, local customs, and tion with personal expression (3). The primary purpose of human endeavor document a thriving arts scene in an era weaving was storytelling. In Greek mythology, skilled often labeled the “Dark Ages.” Arachne challenged Athena, the goddess of wisdom and The tapestries, whose origins and history are as myste- patron of the loom, to a contest.