History of Schooling and in Venda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

A Short Chronicle of Warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau*

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 3, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za A short chronicle of warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau* Khoisan Wars tween whites, Khoikhoi and slaves on the one side and the nomadic San hunters on the other Khoisan is the collective name for the South Afri- which was to last for almost 200 years. In gen- can people known as Hottentots and Bushmen. eral actions consisted of raids on cattle by the It is compounded from the first part of Khoi San and of punitive commandos which aimed at Khoin (men of men) as the Hottentots called nothing short of the extermination of the San themselves, and San, the names given by the themselves. On both sides the fighting was ruth- Hottentots to the Bushmen. The Hottentots and less and extremely destructive of both life and Bushmen were the first natives Dutch colonist property. encountered in South Africa. Both had a relative low cultural development and may therefore be During 18th century the threat increased to such grouped. The Colonists fought two wars against an extent that the Government had to reissue the the Hottentots while the struggle against the defence-system. Commandos were sent out and Bushmen was manned by casual ranks on the eventually the Bushmen threat was overcome. colonist farms. The Frontier War (1779-1878) The KhoiKhoi Wars This term is used to cover the nine so-called "Kaffir Wars" which took place on the eastern 1st Khoikhoi War (1659-1660) border of the Cape between the Cape govern- This was the first violent reaction of the Khoikhoi ment and the Xhosa. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

Clergy's Resistance to VENDA Homeland's INDEPENDENCE in the 1970S and 1980S

CLERGY’S Resistance to VENDA HOMELAND’S INDEPENDENCE IN THE 1970S and 1980S S.T. Kgatla Research Institute for Theology and Religion University of South Africa [email protected] ABSTRACT The article discusses the clergy’s role in the struggle against Venda’s “independence” in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as resistance to the apartheid policy of “separate development” for Venda. It also explores the policy of indirect white rule through the replacement of real community leaders with incompetent, easily manipulated traditional chiefs. The imposition of the system triggered resistance among the youth and the churches, which led to bloody reprisals by the authorities. Countless were detained under apartheid laws permitting detention without trial for 90 days. Many died in detention, but those responsible were acquitted by the courts of law in the Homeland. The article highlights the contributions of the Black Consciousness Movement, the Black People Conversion Movement, and the Student Christian Movement. The Venda student uprising was second in magnitude only to the Soweto uprising of 16 June 1976. The torture of ministers in detention and the response by church leaders locally and internationally, are discussed. The authorities attempted to divide the Lutheran Church and nationalise the Lutherans in Venda, but this move was thwarted. venda was officially re-incorporated into South Africa on 27 April 1994. Keywords: Independence; resistance; churches; struggle; Venda Homeland university of south africa Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2412-4265/2016/1167 Volume 42 | Number 3 | 2016 | pp. 121–141 Print ISSN 1017-0499 | Online 2412-4265 https://upjournals.co.za/index.php/SHE © 2017. -

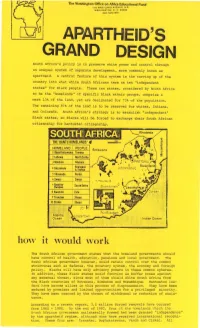

Apartheid's Grand Design

The Washington Office on Africa Educational Fund 110 MARYLAND AVENUE. N .E. WASHINGTON. 0. C. 20002 (202) 546-7961 APARTHEID'S GRAND DESIGN South Africa's policy is to preserve white power and control through an unequal system of separate development, more commonly known as apartheid. A central feature of this system is the carving up of the country into what white South Africans term as ten "independent states" for Black people. These ten states, considered by South Africa to be the "homelands" of specific Black ethnic groups, comprise a mere 13% of the land, yet are designated for 73% of the population. The remaining 87% of the land is to be reserved for whites, Indians, and Coloreds. South Africa's strategy is to establish "independent" Black states, so Blacks will be forced to exchange their South African citizenship for bantustan citizenship. THE 'BANTU HOMELANDS' 4 HOMELAND I PEOPLE I Boputhatswanai Tswana 2 lebowa I North Sotho -~ Hdebete Ndebe!e 0 Shangaan Joh<tnnesourg ~ Gazankulu & Tsonga 5 Vhavenda Venda --~------l _ ______6 Swazi 1 1 ___Swazi_ _ _ '7 Basotho . Qwaqwa South Sotho 8 Kwazulu 9 Transkei 10 Ciskei It• vvould w-ork The South African government states that the homeland governments should have control of health, education, pensions and local government. The South African government however, would retain control over t h e common structures such as defense, the monetary s y stem, the economy and foreign policy . Blacks wi ll have only advisory powers in these common spheres. In addition, these Black states would function as buffer zones against any external threat, since most of them shield white South Africa from the Black countries of Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. -

South Africa Fact Sheet

Souher Afrc Pesecie 1/88 South Africa Fact Sheet Thirty-four million people live in South Africa today, yet only 4.9 million whites have full rights of citizenship. The Black population of 28 million has no political power and is subject to strict government controls on where to live, work, attend school, be born and be buried. This Is the apartheid system which produces enormous wealth for the white minority and grinding poverty for millions of Black South Africans. Such oppression has fueled a rising challenge to white minority rule in the 1980's through strikes, boycotts, massive demonstrations and stayaways. International pressure on the white minority government has also been growing. In response, the government has modified a few existing apartheid laws without eliminating the basic structure of apartheid. This so called reform program has done nothing to satisfy Black South Africans' demands for majority rule in a united, democratic and nonracial South Africa. Struggling to reassert control, the government has declared successive states of emergency and unleashed intensive repression, seeking to conceal its actions by a media blackout, press censorship and continuing propaganda about change. As part of its "total strategy" to preserve white power, Pretoria has also waged war against neighboring African states in an effort to end their support for the anti-apartheid struggle and undermine regional efforts to break dependence on the apartheid economy. This Fact Sheet is designed to get behind the white government's propaganda shield and present an accurate picture of apartheid's continuing impact on the lives of millions of Blacks In southern Africa. -

The Political Origins of Zulu Violence During the 1994 Democratic Transition of South Africa

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AND AREA STUDIES 41 Volume 15, Number 2, 2008, pp.41-54 The Political Origins of Zulu Violence during the 1994 Democratic Transition of South Africa Jungug Choi One of the most interesting cases of the third wave of democratization around the world is that of South Africa in 1994. We have a great magnitude of literature on the South African regime change. Most studies focus on the power struggle between the African National Congress (ANC) and the then governing National Party (NP) or between the Blacks and the Whites or on the type of democratic institutions to be adopted in the post-transitional period. Yet, few have addressed the issue of why the largest black ethnic group of Zulus played a “spoiler” during the transition to democracy. This study deals with the issue of why many Zulus, represented by the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), collaborated with the Whites to wage bloody struggles against other Black “brothers,” although they themselves had belonged to the repressed in the system of apartheid. This study begins with an introduction to the Zulu ethnic group and its nationalism in order to provide preliminary information about who the Zulus are. This is followed by our explanation for why they were engaged in violent conflicts with the other Blacks. Keywords: democratic transition, ethnicity, violence, simple majority rule, consensual democracy, majoritarian democracy, nationalism, Zulu 1. INTRODUCTION One of the most interesting cases of the third wave of democratization around the world is that of South Africa in 1994. We have a great magnitude of literature on the South African regime change. -

2 Brief Political History of South Africa

2 Brief Political History of South Africa Introduction This chapter discusses the various African communities in the broader southern Africa, their various interactions with one another and the interactions with non- African peoples. The chapter also describes how the various African communities such as the San, Khoi, Nguni, Sotho and Tswana managed their socio-economic and political systems. The role and interactions of non-African communities, such as the Portuguese, the Dutch and the English with African communities are also discussed. In the main, European colonialism negatively impacted the African communities. It is in this context that history is critical in order that the understanding of the post-apartheid political economy is not divorced from the totality of the historical experience that has influenced today’s political economy. The history of southern Africa can be said to be not a single narrative or story but rather a series of contested histories that have been altered and remodelled to shape non-African communities and institutions.32 That is why this chapter examines the pre-colonial African communities and the key developments which characterised their societies. The chapter also gives a brief background explanation on how South Africa’s pre-colonial history was manipulated in order to misrepresent the fact that African peoples/communities did in fact have vibrant and functional pre-colonial interactions and societies. In describing the history of southern Africa, it is important to first acknowledge the fact that the history did not begin with the Portuguese or British or Dutch (European) arrival, but is rather an interrupted narrative of socio-economic development.33 There were many African communities that co-existed in southern Africa before the arrival of Europeans – and there were various advanced kingdoms, as epitomised by civilisations pertaining to Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe for example. -

Action Alert Hospital Workers Detained in Venda Bantustan

198 Broadway • New York, N.Y. 10038 • (212) 962-1210 Tilden J. LeMelle, Chairman Jennifer Davis, Executive Director ACTION ALERT HOSPITAL WORKERS DETAINED IN VENDA BANTUSTAN April 24, 1991 Nine members of the National Education, Health and Allied Workers Union (NEHAWU) were detained on April 22 by apartheid authorities in the Venda b~ntustan. The nine a:oc:: e:o_mong l9 hospit~.l workers fired earlier this year after leading a strike at Venda's Siloam hospital against incompetent and racist doctors. According to COSATU officials in Venda, the nine have no legal representation and are unable to post the R2,000 ($800) demanded by the bantustan police. The Venda security forces are notorious even by South African standards for their use of torture against trade union, church and anti-apartheid activists. For that reason there is grave concern for the safety of the detainees, and urgent action is needed to win their release. The arrests are the latest incidents in an escalating campaign of repression and violence directed against NEHAWU by the apartheid government and its allies. Hundreds of Black nurses currently face de-certification and dismissal by the government for joining NEHAWU strikes last year for recognition agreements and higher wages. NEHAWU President Beki Mkhize has been the target of two assassination attempts this year alone. Health workers appear to have been targeted because they often confront the government directly in state-run hospitals and schools. The repression may also be an attempt by the white authorities to break the union before constitutional negotiations begin. NEHAWU would be a major obstacle to any effort to maintain white privilege and control of education and health care in South Africa. -

South Africa's Black Homelands: Past Objectives, Present Realities and Future Developments

SPECIAL STUDY/SPESIALE STUDIE TH£ SOUTH AFRICA'S BLACK HOMELANDS: PAST OBJECTIVES, PRESENT REALITIES AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS Deon Geldenhuys THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS DIE SUID-AFRIKAANSE INSTITUUT VAN INTERNASIONALE AANGELEENTHEDE Peon Geldenhuys is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the Rand Afrikaans University, Johannesburg. At the time of writing this paper he was Assistant Director, Research, at the South African Institute of International Affairs. The last section of this paper was published as "South Africa's Black Homelands: Some Alternative Political Scenarios", in Journal of Contemporary African Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, April 1981# It should be noted that any opinions expressed in this article are the responsibility of the author and not of the Institute. SOUTH AFRICA? S BLACK HOMELANDS: PAST OBJECTIVES, PRESENT REALITIES AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS Deon Geldenhuys Contents Introduction ... page 1 I From native reserves to independent homelands: legislating for territorial separation 3 II Objectives of the homelands policy, post-1959 6 III Present realities: salient features of the independent and self-governing homelands 24 IV Future Developments 51 Conclusion 78 ISBN: 0-909239-89-4 The South African Institute of International Affairs Jan Smuts House P.O. Box 31596 BRAAMFONTEIN 2017 South Africa August 1981 Price R3-50 South Africa's Black Homelands: Past Objectives, Present Realities and Future Developments Introduction A feature of the South African political scene today is the lack of consensus on a desirable future political dispensation. This is reflected in the intensity of the debate about the Republic's political options. Local opinions cover a wide spectrum, ranging from the white 'right' to the black 'left1, i.e. -

Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture Author(S): Thomas N

South African Archaeological Society Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture Author(s): Thomas N. Huffman Source: Goodwin Series, Vol. 8, African Naissance: The Limpopo Valley 1000 Years Ago (Dec., 2000), pp. 14-29 Published by: South African Archaeological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3858043 Accessed: 29-08-2017 14:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms South African Archaeological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Goodwin Series This content downloaded from 196.42.88.36 on Tue, 29 Aug 2017 14:34:12 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 14 South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 8: 14-29, 2000 MAPUNGUBWE AND THE ORIGINS OF THE ZIMBABWE CULTURE* THOMAS N. HUFFMAN Department of Archaeology University ofthe Witwatersrand Private Bag 3 Wits 2050 E-mail: 107arcl(dlcosmos. wits. ac.za ABSTRACT Advances in the calibration of radiocarbon dates (Vogel et al 1993) in particular have resolved critical chronological Class distinction and sacred leadership characterised issues. The the Zimbabwe culture sequence can now be divided Zimbabwe culture, the most complex society in precolonial into three periods, each named after important capitals: southern Africa. -

South African Music in Global Context

South African Music in Global Perspective Gavin Steingo Assistant Professor of Music University of Pittsburgh South African Music * South African music is a music of interaction, encounter, and circulation * South African music is constituted or formed through its relations to other parts of the world * South African music is a global music (although not evenly global – it has connected to different parts of the world at different times and in different ways) Pre-Colonial South African Music * Mainly vocal * Very little drumming * Antiphonal (call-and-response) with parts overlapping * Few obvious cadential points * Partially improvisatory * “Highly organized unaccompanied dance song” (Coplan) * Instruments: single-string bowed or struck instruments, reed pipes * Usually tied to social function, such as wedding or conflict resolution Example 1: Zulu Vocal Music Listen for: * Call-and-Response texture * Staggered entrance of voices * Ending of phrases (they never seem very “complete”) * Subtle improvisatory variations Example 2: Musical Bow (ugubhu) South African History * 1652 – Dutch settle in Cape Town * 1806 – British annex Cape Colony * 1830s – Great Trek * 1867 – Discovery of diamonds * 1886 –Discovery of gold * 1910 – Union of South Africa * 1913 – Natives’ Land Act (“natives” could only own certain parts of the country) * 1948 – Apartheid formed * Grand apartheid (political) * Petty apartheid (social) * 1990 – Mandela released * 1994 – Democratic elections Early Colonial History: The Cape of Good Hope Cape Town * Dutch East India Company