John Harbison's Simple Daylight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

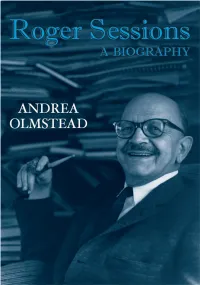

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with Guest Janice Felty, Mezzo-Soprano Now Again

Network for Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with guest Janice Felty, mezzo-soprano Now Again Music by Bernard Rands Network for New Music Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor www.albanyrecords.com TROY1194 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 with guest Janice Felty, tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd mezzo-soprano tel: 01539 824008 © 2010 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. The story is probably apocryphal, but it was said his students at Harvard had offered a prize to anyone finding a wantonly decorative note or gesture in any of Bernard Rands’ music. Small ensembles, single instrumental lines and tones convey implicitly Rands’ own inner, but arching, songfulness. In his recent songs, Rands has probed the essence of letter sounds, silence and stress in a daring voyage toward the center of a new world of dramatic, poetic expression. When he wrote “now again”—fragments from Sappho, sung here by Janice Felty, he was also A conversation between composer David Felder and filmmaker Elliot Caplan about Shamayim. refreshing his long association with the virtuosic instrumentalists of Network for New Music, the Philadelphia ensemble marking its 25th year in this recording. These songs were performed in a 2009 concert for Rands’ 75th birthday — and offer no hope for winning the prize for discovering extraneous notes or gestures. They offer, however, an intimate revelation of the composer’s grasp of color and shade, his joy in the pulsing heart, his thrill at the glimpse of what’s just ahead. -

Identifying Common Hand Position and Posture Problems with Young Musicians

Identifying Common Hand Position and Posture Problems with Young Musicians Flute: Students should not allow their right elbow angle to be tucked into their side—this will angle the flute down. Students need to use the pads of their fingers and not let their fingers hang over the keys. In addition, their fingers should not “fly high” but should stay close to the keys. Oboe: Watch the angle of the instrument. Often, oboe students play too close into their body and close off the reed. Sometimes, they also lower their head and this decreases lower lip pressure, resulting in unfocused tone and flat pitch. Their fingers need to stay low and close to the keys. Encourage students to not bite down, which closes off the reed. You should teach the correct combination of corner firmness and open reed akin to drinking a thick milkshake. Bassoon: It’s important for students to “bring the instrument to YOU, not you to the bassoon.” Sometimes students struggle with holding the instrument and it’s important that the angle of the instrument be over the left shoulder. Watch the hand position for the whisper key F—students should keep the hand position flat and horizontal, not angled. Clarinet: The top teeth should be on top of the mouthpiece and the teeth should be at the fulcrum, the place where the reed meets the mouthpiece. Most clarinetists don’t put enough mouthpiece in the mouth. Focus heavily on a flat chin. Make sure the fingers stay curved as if holding a tennis ball and the fingers should be straight across, not angled (students like to angle their fingers to rest on the side keys). -

Female Composer Segment Catalogue

FEMALE CLASSICAL COMPOSERS from past to present ʻFreed from the shackles and tatters of the old tradition and prejudice, American and European women in music are now universally hailed as important factors in the concert and teaching fields and as … fast developing assets in the creative spheres of the profession.’ This affirmation was made in 1935 by Frédérique Petrides, the Belgian-born female violinist, conductor, teacher and publisher who was a pioneering advocate for women in music. Some 80 years on, it’s gratifying to note how her words have been rewarded with substance in this catalogue of music by women composers. Petrides was able to look back on the foundations laid by those who were well-connected by family name, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, and survey the crop of composers active in her own time, including Louise Talma and Amy Beach in America, Rebecca Clarke and Liza Lehmann in England, Nadia Boulanger in France and Lou Koster in Luxembourg. She could hardly have foreseen, however, the creative explosion in the latter half of the 20th century generated by a whole new raft of female composers – a happy development that continues today. We hope you will enjoy exploring this catalogue that has not only historical depth but a truly international voice, as exemplified in the works of the significant number of 21st-century composers: be it the highly colourful and accessible American chamber music of Jennifer Higdon, the Asian hues of Vivian Fung’s imaginative scores, the ancient-and-modern syntheses of Sofia Gubaidulina, or the hallmark symphonic sounds of the Russian-born Alla Pavlova. -

Document Cover Page

A Conductor’s Guide and a New Edition of Christoph Graupner's Wo Gehet Jesus Hin?, GWV 1119/39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Seal, Kevin Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 06:03:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645781 A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN?, GWV 1119/39 by Kevin M. Seal __________________________ Copyright © Kevin M. Seal 2020 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by: Kevin Michael Seal titled: A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN, GWV 1119/39 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 3, 2020 John T Brobeck _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Rex A. Woods Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

An Analysis and Performance Considerations for John

AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN (Under the Direction of D. RAY MCCLELLAN) ABSTRACT John Harbison is an award-winning and prolific American composer. He has written for almost every conceivable genre of concert performance with styles ranging from jazz to pre-classical forms. The focus of this study, his Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, was premiered in 1985 as a product of a Consortium Commission awarded by the National Endowment of the Arts. The initial discussions for the composition were with oboist Sara Bloom and clarinetist David Shifrin. Harbison’s Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings allows the clarinet to finally be introduced to the concerto grosso texture of the Baroque period, for which it was born too late. This document includes biographical information on John Harbison including his life and career, compositional style, and compositional output. It also contains a brief history of the Baroque concerto grosso and how it relates to the Harbison concerto. There is a detailed set-class analysis of each movement and information on performance considerations. The two performers as well as the composer were interviewed to discuss the commission, premieres, and theoretical/performance considerations for the concerto. INDEX WORDS: John Harbison, Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, clarinet concerto, oboe concerto, Baroque concerto grosso, analysis and performance AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN B.M., Tennessee Technological University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Katherine Belvin All Rights Reserved AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN Major Professor: D. -

Gesungene Aufklärung

Gesungene Aufklärung Untersuchungen zu nordwestdeutschen Gesangbuchreformen im späten 18. Jahrhundert Von der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg – Fachbereich IV Human- und Gesellschaftswissenschaften – zur Erlangung des Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von Barbara Stroeve geboren am 4. Oktober 1971 in Walsrode Referent: Prof. Dr. Ernst Hinrichs Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning Tag der Disputation: 15.12.2005 Vorwort Der Anstoß zu diesem Thema ging von meiner Arbeit zum Ersten Staatsexamen aus, in der ich mich mit dem Oldenburgischen Gesangbuch während der Epoche der Auf- klärung beschäftigt habe. Professor Dr. Ernst Hinrichs hat mich ermuntert, meinen Forschungsansatz in einer Dissertation zu vertiefen. Mit großer Aufmerksamkeit und Sachkenntnis sowie konstruktiv-kritischen Anregungen betreute Ernst Hinrichs meine Promotion. Ihm gilt mein besonderer Dank. Ich danke Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning für die Bereitschaft, mein Vorhaben zu un- terstützen und deren musiktheoretische und musikhistorische Anteile mit großer Sorgfalt zu prüfen. Mein herzlicher Dank gilt Prof. Dr. Hermann Kurzke, der meine Arbeit geduldig und mit steter Bereitschaft zum Gespräch gefördert hat. Manche Hilfe erfuhr ich durch Dr. Peter Albrecht, in Form von wertvollen Hinweisen und kritischen Denkanstößen. Während der Beschäftigung mit den Gesangbüchern der Aufklärung waren zahlreiche Gespräche mit den Stipendiaten des Graduiertenkollegs „Geistliches Lied und Kirchenlied interdisziplinär“ unschätzbar wichtig. Stellvertretend für einen inten- siven, inhaltlichen Austausch seien Dr. Andrea Neuhaus und Dr. Konstanze Grutschnig-Kieser genannt. Dem Evangelischen Studienwerk Villigst und der Deutschen Forschungsge- meinschaft danke ich für ihre finanzielle Unterstützung und Förderung während des Entstehungszeitraums dieser Arbeit. Ich widme diese Arbeit meinen Eltern, die dieses Vorhaben über Jahre bereit- willig unterstützt haben. -

Le Corsaire Overture, Op. 21

Any time Joshua Bell makes an appearance, it’s guaranteed to be impressive! I can’t wait to hear him perform the monumental Brahms Violin Concerto alongside some fireworks for the orchestra. It’s a don’t-miss evening! EMILY GLOVER, NCS VIOLIN Le Corsaire Overture, Op. 21 HECTOR BERLIOZ BORN December 11, 1803, in Côte-Saint-André, France; died March 8, 1869, in Paris PREMIERE Composed 1844, revised before 1852; first performance January 19, 1845, in Paris, conducted by the composer OVERVIEW The Random House Dictionary defines “corsair” both as “a pirate” and as “a ship used for piracy.” Berlioz encountered one of the former on a wild, stormy sea voyage in 1831 from Marseilles to Livorno, on his way to install himself in Rome as winner of the Prix de Rome. The grizzled old buccaneer claimed to be a Venetian seaman who had piloted the ship of Lord Byron during the poet’s adventures in the Adriatic and the Greek archipelago, and his fantastic tales helped the young composer keep his mind off the danger aboard the tossing vessel. They landed safely, but the experience of that storm and the image of Lord Byron painted by the corsair stayed with him. When Berlioz arrived in Rome, he immersed himself in Byron’s poem The Corsair, reading much of it in, of all places, St. Peter’s Basilica. “During the fierce summer heat I spent whole days there ... drinking in that burning poetry,” he wrote in his Memoirs. It was also at that time that word reached him that his fiancée in Paris, Camile Moke, had thrown him over in favor of another suitor. -

Days of Bliss Are in Store: Antonino Pasculli's "Gran Trio Concertante

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Days of Bliss Are in Store: Antonino Pasculli's Gran Trio Concertante per Violino, Oboe, e Pianoforte su Motivi del Guglielmo Tell di Rossini Anna Pennington Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC DAYS OF BLISS ARE IN STORE: ANTONINO PASCULLI’S GRAN TRIO CONCERTANTE PER VIOLINO, OBOE, E PIANOFORTE SU MOTIVI DEL GUGLIELMO TELL DI ROSSINI By ANNA PENNINGTON A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music. Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2007 Copyright © 2007 Anna Pennington All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Anna Pennington defended on May 7, 2007. ______________________________ Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise ______________________________ Richard Clary Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Frank Kowalsky Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the generous encouragement of Eric Ohlsson in completing this project, I am greatly indebted. I also wish to thank Sandro Caldini and Olga Visentini, for their unselfish help in obtaining the trio. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................... v -

The Great Gatsby – Opening of Chapter 3

The Great Gatsby – Opening of Chapter 3 The Great Gatsby is a novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, set in 1920s America. It is narrated by Nick Carraway, a man in his late 20s, who has moved to Long Island to commute to his job in New York City trading bonds. He moves next door to Jay Gatsby, a man who has earned a reputation for an extravagant lifestyle but is a somewhat enigmatic figure. At this point in the novel, Nick hasn’t even met Gatsby, despite hearing a lot about him. There was music from my neighbor’s house through the summer nights. In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars. At high tide in the afternoon I watched his guests diving from the tower of his raft, or taking the sun on the hot sand of his beach while his two motor-boats slit the waters of the Sound, drawing aquaplanes over cataracts of foam. On week-ends his Rolls- Royce became an omnibus, bearing parties to and from the city between nine in the morning and long past midnight, while his station wagon scampered like a brisk yellow bug to meet all trains. And on Mondays eight servants, including an extra gardener, toiled all day with mops and scrubbing-brushes and hammers and garden-shears, repairing the ravages of the night before. Every Friday five crates of oranges and lemons arrived from a fruiterer in New York — every Monday these same oranges and lemons left his back door in a pyramid of pulpless halves. -

Johannes-Passion

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 1685-1750 JOHANNES-PASSION BWV 244 (1727, revisie 1736) op teksten van Barthold Heinrich Brockes en anderen ZANGTEKSTEN Uitgave van Preludium, muziekmagazine van Het Concertgebouw en het Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest www.preludium.nl 1 MATTHÄUS-PASSION EERSTE DEEL 1 Koor Herr, unser Herrscher, dessen Ruhm in allen Landen herrlich ist! Zeig uns durch deine Passion, dass du, der wahre Gottessohn, zu aller Zeit, auch in der grössten Niedrigkeit, verherrlicht worden bist! JOHANNES XVIII 2a Evangelist Jesus ging mit seinen Jüngern über den Bach Kidron, da war ein Garte, da rein ging Jesus und seine Jünger. Judas aber, der ihn verriet, wusste den Ort auch, denn Jesus versammlete sich oft daselbst mit seinen Jüngern. Da nun Judas sich hatte genommen die Schar und der Hohenpriester und Pharisäer Diener, kommt er dahin mit Fakkeln, Lampen und mit Waffen. Als nun Jesus wusste alles, was ihm begegnen sollte, ging er hinaus und sprach zu ihnen: Jezus Wen suchet ihr? Evangelist Sie antworteten ihm: 2b Koor Jesum von Nazareth. 2c Evangelist Jesus spricht zu ihnen: 2 Jezus Ich bins. Evangelist Judas aber, der ihn verriet, stund auch bei ihnen. Als nun Jesus zu ihnen sprach: Ich bins, wichen sie zurükke und fielen zu Boden. Da fragete er sie abermal: Jezus Wen suchet ihr? Evangelist Sie aber sprachen: 2d Koor Jesum von Nazareth. 2e Evangelist Jesus antwortete: Jezus Ich habs euch gesagt, dass ichs sei, suchet ihr denn mich, so lasset diese gehen! 3 Koraal O grosse Lieb, o Lieb ohn alle Masse, die dich gebracht auf diese Marterstrasse! Ich lebte mit der Welt in Lust und Freuden, und du musst leiden. -

J.E. Gardiner (SDG

Cantatas for Quinquagesima King’s College Chapel, Cambridge This concert was significant in several ways. Firstly, it contained Bach’s two ‘test’ pieces for the cantorship at St Thomas’s in Leipzig, BWV 22 and BWV 23, designed to be performed within a single service either side of the sermon on 7 February 1723. Then Quinquagesima being the last Sunday before Lent, it was accordingly the final opportunity Leipzigers had of hearing music in church before the statutory tempus clausum that lasted until Vespers on Good Friday, and Bach seemed determined to leave them with music – four cantatas – that they wouldn’t easily forget. Thirdly, by coincidence, in 2000 Quinquagesima fell on 5 March, thirty-six years to the day since I first conducted Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 in King’s College Chapel as an undergraduate. The Monteverdi Choir was born that night. I was pleased to be returning to King’s for this anniversary, and to invite the four collegiate choirs from which I had recruited the original Monteverdians to join with us in the singing of the chorales at the start of the concert. Of these, the choirs of Clare and Trinity Colleges responded positively. King’s Chapel seemed to work its unique Gothic alchemy on the music, though, as ever, one needed to be on one’s guard against the insidious ‘tail’ of its long acoustic which can turn even the most robust music-making into mush. St Luke’s Gospel for Quinquagesima recounts two distinct episodes, of Jesus telling the disciples of his coming Passion and of sight restored to a blind man begging near Jericho.