Historiography of the Jihad Movement:A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSLIM LEADERSHIP in U. P. 1906-1937 ©Ottor of ^Liilogoplip

MUSLIM LEADERSHIP IN U. P. 1906-1937 OAMAV''^ ***' THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF ©ottor of ^liilogoplip IN Jlis^torp Supervisor Research scholar umar cKai Head Department of History Banaras Hindu University VaranaSi-221005 FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY VARANASI-221005 Enrolment No.-l 73954 Year 1994 D©NATED BY PROF Z. U. SIDDIQUI DEPT. OF HISTORY. A.M.U. T5235 Poll * TtU. OJfiet : BADUM Hindu Univenity Q»3H TeUphone : 310291—99 (PABX) Sailwaj/Station Vkranui Cantt. SS^^/ Telex ;645 304 BHU IN Banaras Hindu University VARANASI—221005 R^. No..^ _ IMPARWBif 99 HliiOllir 2)ate<i - 9lftlfltilt Bft#fi titii Stall flf Ifti ffti1?t QfilifllfttI !Uiiitii X te*M^ c«rtify tHat ttM thatit •! Sti A^«k Kunat fttl. MiltUd ^Htfllii tM&mw^tp III U.F, ElitwMfi (t9%^im)»* Htm f««i»««^ fdMlAi iHMlit mf awp«rviai«n in tti« D»p«ftMifit of Hitt^y* Facility 9i So€i«d SdL«nc«t« n&ntwmM Hindu Ufiiv«rtity« ™—- j>v ' 6 jjj^ (SUM.) K.S. SMitte 0»»««tMllt of ^tj^£a»rtmentrfHj,,0| ^ OO^OttMOt of Hittflf SaAovoo Hin^ llRiiSaSu^iifi Sec .. ^^*^21. »«»•»•• Htm At Uiivovoity >^otflR«ti • 391 005' Dep«tfY>ent of History FACULTY OF SOCIAL S' ENCES Bsnafas Hir-y Unlvacsitv CONTENTS Page No. PREFACE 1 - IV ARBRBVIATIONS V INTRODUCTION ... 1-56 CHAPTER I : BIRTH OF fvUSLiM LEAaJE AND LEADERSHIP IN U .P . UPTO 1916 ... 57-96 CHAPTER II MUSLIM LEADERSHIP IN U .P . DURING KHILAFAT AND NON CO-OPERATION MO ^fAENT ... 97-163 CHAPTER III MUSLIM POLITICS AND LEADERSHIP IN U.P, DURING Sy/AR.AJIST BRA ...164 - 227 CHAPTER IV : MUSLL\^S ATflTUDE AND LEADERSHIP IN U.P. -

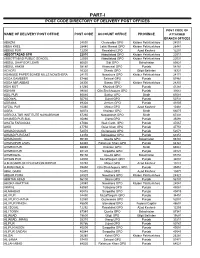

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Puma Energy Pakistan (Private) Limited

11 Puma Energy Pakistan (Private) Limited Pumps Retail Prices of HSD and PMG Effective from 01st August, 2021 Pump Price Rs / Liter S.No Customer Name Address City HSD PMG 1 A. K. MANN PETROLEUM Chak # 112/7R, T. T. Singh-Burewala Road Toba Taik Singh 117.58 120.80 2 A.A ENTERPRISES SHAHPUR JAHANIAN TEHSIL MORO DISTRICT Daulatpur 117.05 120.29 3 A.Q MALIKANI PETROLEUM SERVICES Survey No.32 Deh Sattar Dino Shah,Tapo Mullan Dist Thatta 117.75 120.96 4 A.S PETROLEUM SERVICE Mouza Naroki Majaha, Pattoki-Changa Manga Road Pattoki 117.48 120.70 At Aray Wala Mouza Pakki (Near Qasba Shah Sadar Din)KM 26/27 From Dera Gazi Khan, Tunsaroad Indus 5 AADIL PETROLEUM SERVICES Dera Ghazi Khan 117.05 120.29 N-55 6 ABBAS FILLING STATION Block # 165/3 & 4, Sub #3A-3B-4A & 4B, Deh 86Nasrat Main Sanghar Road Nawabshah 117.05 120.29 7 ABBAS PETROLEUM STATION Kharian Dinga Road Noonan Wali Distt GujratNoonan Wali Noonan Wali - Gujrat 117.05 120.29 8 Abbasi Trucking Station Moro Servery No. 475, Situated in Deh Moro & Taluka Mo Moro 117.05 120.29 9 ABBASIA FILLING STATION Taluka Gularchi Plot No.A3 Khi Road, Shaheed Fazil Badin 117.93 121.12 10 ABDUL RAFAY PETROLEUM Mouza Kotla Qasim Khan Dinga Road, Tehsil Lala Mou Gujrat 117.05 120.29 11 ABDUL SATTAR PETROLEUM SERVICE Mouza Manga Ottar, (Near Honda Factory), on Nationon National Highway (N-5) (South Bond) Lahore 117.24 120.48 12 ABDULLAH PETROLEUM Chak Beli Khan / Rawalpindi Road, Tehsil & Distt Rawalpindi Rawal Pindi 117.05 120.29 13 ABDULLAH PETROLEUM STATION- GUJRAT Mouza Ganja B/W KM 8/9 From Lala Mopuza On NoonwalOn Noonwali-Ganja-Lala Mouza Road Gujrat 117.05 120.29 14 ABDULLAH PETROLEUM SERVICE Petrol Pump Baloch AJK, Baloch Sadhnoti AJK 117.48 120.70 15 ABID CNG STATION & PETROLEUM SERVICES On Jalal Pur Pirwala Road At Mouza KhaipurOpposite Al-Shamas At Shujanad Multan 117.16 120.40 16 ADIL FILLING STATION Survey No. -

Online First Article

Pakistan J. Zool., pp 1-11, 2021. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjz/20190927080941 Identification of Genetic Lineage of Peshawar and Nowshera Tribes through Dental Morphology Muhammad Zubair1, Habib Ahmad2*, Brian E. Hemphill3, Muhammad Tariq4 and Muzafar Shah5 1Department of Zoology, Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan 2Department of Genetics, Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan 3Department of Anthropology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, USA 4 Center for Omic Sciences, Islamia College Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan Article Information 5Centre for Animal Sciences and Fisheries, University of Swat, Swat, Pakistan Received 27 September 2019 Revised 22 December 2019 Accepted 23 January 2020 ABSTRACT Available online 27 July 2020 Authors’ Contribution Analyzing the diversity of non metric phenotypic traits of the mature teeth, in three ethnic groups’ viz. HA and BEH conceived the idea Daudzai, Khalil and Mohmand of Peshawar districts, of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KP) of and designed the research project. Pakistan. Dental casts obtained from both mandible and maxilla of 375 volunteers in which 75 male MZ and MS conducted sampling and 50 females of all the tribes. The dental casts for each individual were analyzed for a set of 35 tooth- and generated data. MZ and MT trait accordance with the Arizona State University Dental Morphology System. The data was compared performed the data analysis. MZ and MS drafted the manuscript. BEH and with the secondary information of 3842 individuals representing 36 other ethnic groups of different parts HA reviewed the manuscript. of KP, peninsular India prehistoric samples of Indus valley Central Asia and South Asia. Inter sample affinities based upon pair wise MMD values were examined with neighbor-joining cluster analysis and Key words multidimensional scaling. -

1 Annexure - D Names of Village / Neighbourhood Councils Alongwith Seats Detail of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

1 Annexure - D Names of Village / Neighbourhood Councils alongwith seats detail of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa No. of General Seats in No. of Seats in VC/NC (Categories) Names of S. Names of Tehsil Councils No falling in each Neighbourhood Village N/Hood Total Col Peasants/Work S. No. Village Councils (VC) S. No. Women Youth Minority . district Council Councils (NC) Councils Councils 7+8 ers 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Abbottabad District Council 1 1 Dalola-I 1 Malik Pura Urban-I 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 2 Dalola-II 2 Malik Pura Urban-II 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 3 Dabban-I 3 Malik Pura Urban-III 5 8 13 4 2 2 2 4 Dabban-II 4 Central Urban-I 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 5 Boi-I 5 Central Urban-II 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 6 Boi-II 6 Central Urban-III 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 7 Sambli Dheri 7 Khola Kehal 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 8 Bandi Pahar 8 Upper Kehal 5 7 12 4 2 2 2 9 Upper Kukmang 9 Kehal 5 8 13 4 2 2 2 10 Central Kukmang 10 Nawa Sher Urban 5 10 15 4 2 2 2 11 Kukmang 11 Nawansher Dhodial 6 10 16 4 2 2 2 12 Pattan Khurd 5 5 2 1 1 1 13 Nambal-I 5 5 2 1 1 1 14 Nambal-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 Abbottabad 15 Majuhan-I 7 7 2 1 1 1 16 Majuhan-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 17 Pattan Kalan-I 5 5 2 1 1 1 18 Pattan Kalan-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 19 Pattan Kalan-III 6 6 2 1 1 1 20 Sialkot 6 6 2 1 1 1 21 Bandi Chamiali 6 6 2 1 1 1 22 Bakot-I 7 7 2 1 1 1 23 Bakot-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 24 Bakot-III 6 6 2 1 1 1 25 Moolia-I 6 6 2 1 1 1 26 Moolia-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 1 Abbottabad No. -

Nutrition Funding Saves a Boy's Life Hussain Ali Was Too Weak to Walk When Nutrition Officers from the International Catholic

Nutrition funding saves a boy’s life Hussain Ali was too weak to walk when nutrition officers from the International Catholic Migration Commission found him during their routine field visit in Nowshera District in the north-western Pakistan region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where ongoing insecurity has caused humanitarian needs. Ten-month-old Hussain was pale, underweight, malnourished and hardly able to move his hands. After an initial examination, he was referred to basic health unit supported by the International Catholic Migration Commission in Shaidu, a town in Nowshera, for further examination and treatment. The International Catholic Migration Commission had recently received two grants adding up to US$561,856 from OCHA’s Emergency Response Fund (ERF) to implement health and nutrition projects in Nowshera and Charsadda districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. The projects also focused on sensitization of vulnerable communities on disaster risk reduction, gender-based violence and protection. ERF is a mechanism to provide rapid and flexible funds at the onset of an emergency. Hussain’s mother took him the health unit the following day. “My son lies down the whole day. My other children started crawling at this age. He is weak and keeps crying,” his mother told the doctor who examined him. He was diagnosed with severe acute malnutrition, chest infection and other related complications. He was treated for chest infection and diarrhoea and was referred to the Nowshera District Headquarters Hospital and to a nutrition stabilization centre in Mardan District for further treatment. Hussain was admitted to the stabilization centre for malnutrition treatment, which included a daily pack of plumpy nut, a peanut-based paste in a plastic wrapper for treatment of severe acute malnutrition. -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

PART III] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 14, 2019 21(1) ISLAMABAD, MONDAY, JANUARY 14, 2019 PART III Other Notifications, Orders, etc. ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 9th January, 2019 SUBJECT:—NOTIFICATION OF THE RETURNED CANDIDATES IN RESPECT OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT 8TH BYE- ELECTIONS IN KP PROVINCE No. F. 27(1)/2018-LGE-KPK(Vol-I).—In exercise of powers conferred upon it under Article 140A of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Section-86 of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Local Government Act 2013, read with Rule-41 (4) of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Local Councils (Conduct of Elections) Rules, 2014, and all other Powers enabling it in that behalf, the Election Commission of Pakistan is pleased to notify hereunder, for information of general public, the names of returned candidates against the vacant seats in various Local Councils of KP Province elected in the Local Government 8th Bye-Election held on 23rd December, 2018 in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province:— 21(1-15) Price: Rs. 20.00 [42(2019)/Ex. Gaz.] 21(2) THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 14, 2019 [PART III Name of Father/Husband Category of S.No Returned Address Name Seat Candidate DISTRICT PESHAWAR Ward Sikandar Town (Town Council-I) Faqeer 1 Afzal Khan General Gulbahar No.03, Peshawar Muhammad Ward Asia (Town Council-I) Garhi Mir Ahmad Shah, Ramdas, 2 Shah Zeb Muhammad Hanif General Peshawar Ward Yakatoot-I (Town Council-I) Shehbaz Town, Wazir Bagh 3 Bakhtiar Ahmad Sahibzada General Road, Peshawar Ward Akhoonabad (Town Council-I) Haider -

Open Access Journal Home Page: ISSN: 2223-957X C

Int. J. Econ. Environ. Geol. Vol. 10 (3) 129-134, 2019 Ali et al. /Int.J.Econ.Environ.Geol.Vol. 10(3) 129-134, 2019 Open Access Journal home page: www.econ-environ-geol.org ISSN: 2223-957X c Economic Evaluation of Placer Gold Along River Indus From Ghazi to Kund, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan: Implications for Commercial Scale Pilot Plant Liaqat Ali1*, Sajjad Ahmad2, Seema Anjum Khattak1 Naveed Anjum2, Muhammad Waseem1, Asghar Ali2 1 National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 2 Department of Geology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan *Email: [email protected] Received: 27 July, 2019 Accepted: 04 August, 2019 Abstract: A detailed study was conducted on Indus river in order to evaluate the economic potential. Samples were collected for geochemical studies from both stream sediments (SS) and heavy mineral concentrates (HMC) along Indus river from Ghazi, Hund, Beka, Alladher and Kund in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. All the samples were analyzed for gold (Au), silver (Ag) and base metals in order to get information about geochemical associations. Panning and sluice methods were applied for the collection of these samples and extraction of visible gold. Results show that HMC have high Au contents, having maximum value of 44.15 g/t and 39.15 g/t in Kund and Beka areas respectively with an average value of 15.18 g/ton and 11.37 g/ton while the SS have average amount of Au as 0.8 g/t. In both these media higher concentration of gold was found in HMC. On the basis of results from both sampling media, the placer gold deposits in Kund, Alladher and Beka are considered highly economical for the commercial exploration of placer gold. -

International Medical Corps' Needs Assessment in Khyber

International Medical Corps’ Needs Assessment in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan September 23, 2010 Background Six weeks after the start of Pakistan’s worst floods in over 80 years, millions of people continue to depend on assistance as their homes, possessions and livelihoods have been washed away by flood waters. In Khyber Paktunkhwa (KPK) province flood waters have receded, yet more than 900,000 people remain displaced. Health facilities, schools, and other public buildings that are still intact are serving as temporary shelters for those displaced by the floods. As many of these communities were still in the process of rebuilding following last year’s military offensive and subsequent displacement, these floods had an even more devastating effect creating further dependence on relief assistance. Key Findings • While 85 percent of respondents said that they had received some type of food assistance since being displaced, 45 percent feel that currently there is not enough food for their family • Of those surveyed, 31 percent do not have cooking utensils necessary to prepare and serve meals and 48 percent do not have enough fuel to cook • 42 percent do not feel that the latrines available meet the needs of their family and 46 percent of families do not have access to bathing facilities • An alarming 62.5 percent do not have a place to dispose of household waste and therefore just leave it out • 79 percent of respondents said that either they or their family has needed health care services since displacement. Most have sought treatment for acute illnesses such as diarrhea or ARI. -

An Analysis of Syed Ahmad Shaheed's Jihad Movement

Pakistan Vol. 50, 2014 Annual Research Journal STRUGGLE FOR ISLAMIC STATE AND SOCIETY: AN ANALYSIS OF SYED AHMAD SHAHEED’S JIHAD MOVEMENT Dr. Sultan Mahmood ∗∗∗ Hafiz Nasiruddin ∗∗∗∗∗∗ Dr. Muhammad Rizwan ∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗ Abstract Syed Ahmad Shaheed’s Jihad Movement is an important episode of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s history. It played the role of fore-runner of Pakistan Movement in Indian subcontinent. This movement became the source of inspiration to Muslims of India in their struggle for preservation of Muslim culture, protection of their separate identity and establishment of an independent Islamic state in this region of the World. Those Muslims who later struggled for Pakistan saw Syed Ahmad and his followers as role-models fighting bravely against domination of non- Muslim rule and scarifying their lives for the cause of Islam. This study aims to critically examine objectives of Jihad Movement, its achievements and failures and role of people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in it. Study will contribute significantly to understand problems and prospects of Islamization in this region. Keywords: Islam, Jihad Movement, India, NWFP, Culture Introduction Jihad Movement of Syed Ahmad is inevitable and significant component of History of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Due to his sincerity and commitment with the cause of Islam, Syed Ahmad received great respect and love of the people of this region during his stay in this region of Pakistan and is still remembered with respect and reverence. Dr. Jehanzeb Khalil, who belongs to the area of struggle of Syed Ahmad, observes in his doctoral research on Mujahideen Movement: “the purpose behind his struggle was not worldly gain, fame and popularity, but the purpose was to submit to the will of Allah and to follow the Sunnah of the Prophet (PBUH). -

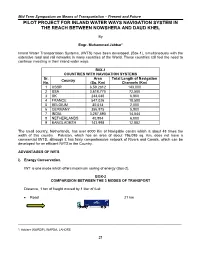

Pilot Project for Inland Water Ways Navigation System in the Reach Between Nowshera and Daud Khel

Mid Term Symposium on Means of Transportation – Present and Future PILOT PROJECT FOR INLAND WATER WAYS NAVIGATION SYSTEM IN THE REACH BETWEEN NOWSHERA AND DAUD KHEL By Engr. Muhammad Jabbar* Inland Water Transportation Systems, (IWTS) have been developed, (Box-1), simultaneously with the extensive road and rail networks in many countries of the World. These countries still feel the need to continue investing in their inland water ways. B0X-1 COUNTRIES WITH NAVIGATION SYSTEMS Sr. Area Total Length of Navigation Country No. (Sq. Km) Channels (Km) 1 USSR 6,59,2812 143,000 2 USA 3,618,770 72,500 3 UK 244,046 6,800 4 FRANCE 547,026 10,500 5 BELGIUM 30,513 2,000 6 GERMANY 356,975 5,900 7 INDIA 3,287,590 14,544 8 NETHERLANDS 40,884 6,000 9 BANGLADESH 143,998 12,882 The small country, Netherlands, has over 6000 Km of Navigable canals which is about 48 times the width of this country. Pakistan, which has an area of about 796,095 sq. Km, does not have a commercial IWTS, although it has fairly comprehensive network of Rivers and Canals, which can be developed for an efficient IWTS in the Country. ADVANTAGES OF IWTS i) Energy Conservation. IWT is one mode which offers maximum saving of energy (Box-2). BOX-2 COMPARISION BETWEEN THE 3 MODES OF TRANSPORT Distance, 1 ton of freight moved by 1 liter of fuel: Road 21 km ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ *: Adviser (NWRDP), WAPDA, LAHORE 27 Engr. Muhammad Jabbar Paper No. 322 Rail 71 K IWT 182 Km Source: US Department of Transport The operating cost of IWT (barges and boats) is very low. -

Nowshera Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (NOWSHERA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH NOWSHERA DISTRICT 1,518,540 198,808 JEHANGIRA TEHSIL 353,490 45,112 AKORA KHATTAK MC 32,883 4363 CHARGE NO 03 32,883 4363 CIRCLE NO 01 14,252 1664 080030101 1,668 226 080030102 1,805 251 080030103 1,130 158 080030104 1,912 260 080030105 1,496 210 080030106 2,372 326 080030107 3,869 233 CIRCLE NO 02 11,262 1683 080030201 2,724 375 080030202 574 74 080030203 2,371 353 080030204 1,404 223 080030205 1,915 305 080030206 1,852 251 080030207 422 102 CIRCLE NO 03 7,369 1016 080030301 874 123 080030302 1,271 171 080030303 1,287 178 080030304 1,539 203 080030305 1,208 174 080030306 1,190 167 JEHANGIRA MC 52,839 6997 CHARGE NO 02 52,839 6997 CIRCLE NO 01 10,483 1307 080020101 4,700 535 080020102 402 57 080020103 2,039 247 080020104 777 106 080020105 1,844 256 080020106 721 106 CIRCLE NO 02 10,557 1370 080020201 1,602 196 080020202 314 38 080020203 821 102 080020204 1,135 133 080020205 2,776 404 080020206 2,903 389 080020207 1,006 108 CIRCLE NO 03 14,132 1764 080020301 3,848 441 080020302 1,182 173 080020303 2,988 414 080020304 2,017 217 Page 1 of 30 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (NOWSHERA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 080020305 1,319 127 080020306 1,001 140 080020307 1,777 252 CIRCLE NO 04 7,872 1087 080020401 1,723 212 080020402 1,827 282 080020403 267 39 080020404 960 114 080020405 1,867 274 080020406 1,228 166 CIRCLE NO 05 9,795 1469 080020501 1,539 221